Launched: Out of Old Ontario Kitchens by Lindy Mechefske

By Laura Rock Gaughan

Welcome to the latest instalment of Launched, the series with the scoop on new books by Canadian authors.

Lindy Mechefske is a Kingston-based writer whose new book, Out of Old Ontario Kitchens, came out in 2018. It is the latest in a provincial series published by Nova Scotia-based MacIntyre Purcell. Her previous books are Sir John’s Table: The Culinary Life and Times of Canada’s First Prime Minister and A Taste of Wintergreen. We discussed Out of Old Ontario Kitchens by email as Lindy was returning from reading at the 1000 Islands Writers Festival.

Q: Why did you write this book? What was the impetus?

The truth is, I’ve fallen in love with culinary history, which is, for the most part, women’s history. The more I read and researched, the more I realized that this book was my feminist manifesto; my chance to pay homage to the women who went before us and all their relentless toil.

Cooking was persistent, hard work–especially in an era before electricity, running water, or a local supermarket. It was work that fell almost exclusively to women. It was women who got up and lit the fires in the hearth, fed babies, and then prepared, preserved, stirred, baked, and cooked food. Women who set the table and did the dishes and kept families alive through long hard winters, and through plagues and depressions, famines and wars, poverty and wealth. And all this endless work was done for no pay, no glory, no mention whatsoever in our high school history textbooks.

Feeding the nation was work that was every bit as important as farming, mining, commerce, politics, and the development of infrastructure–none of which really mattered without someone to tend to the endless task of food preparation.

Q: The book has a sweeping scope, containing culinary history, stories, and recipes. Can you comment on your process–the research and story-gathering? Was it difficult to bring the stories to the fore, given the necessity of also laying down historical markers? And how did you decide which stories to use?

Q: The book has a sweeping scope, containing culinary history, stories, and recipes. Can you comment on your process–the research and story-gathering? Was it difficult to bring the stories to the fore, given the necessity of also laying down historical markers? And how did you decide which stories to use?

I started with a master list of topics I wanted to cover or at least glimpse at: the foods of the Indigenous Peoples and of the waves of emigrants; foods regional to Ontario, such as Red Fife wheat, the McIntosh apple, the fish of the Great Lakes, and butter tarts; and of course, the truly remarkable firsts of Ontario, such as the world’s first electric oven, invented in Ottawa in 1892. And later, in 1906, Hydro Electric of Ontario–the world’s first publicly owned electricity utility and the beginning of a revolution in the kitchen. I added things to my master list almost daily throughout the entire research and writing process!

My search for food stories, recipes, and old food advertisements, photographs, and illustrations took me throughout the province, from north to south and east to west. To Library and Archives Canada and to tiny rural archives run by local volunteers; from university archival cookbook collections to small rural museums; and into the kitchens of women I had never met before, who wanted to share their mother’s or grandmother’s or great-grandmother’s recipes and stories. I delved through boxes and files of ancient letters and newspaper clippings, and through remembrances of the Great Depression and the two World Wars. Everywhere I went, there were astonishing food stories.

I read old cookbooks and delighted in the diaries and accounts of both the famous early females, such as Elizabeth Posthuma Simcoe, Lady Dufferin, Anne Langton, Catharine Parr Traill, Susanna Moodie, Nellie McClung, Pauline Johnson, and Anna Jameson; and the less famous ones, too–some entirely unknown or even anonymous.

At one point, I held in my hands the fragile handwritten cookbook of an unknown woman. A woman who must have been educated, judging by her magnificent penmanship; and who was presumed to be Irish (given the ingredients and types of recipes). Further analysis revealed the book likely dated back to the 1840s and that probably both the book and its author had arrived as a result of the Irish Potato Famine. It is a staggering and poignant thing to hold in your own hands the handwritten pages of an unknown woman, whose tragedies and triumphs we can only begin to guess at. One thing is certain, she must have made the Irish tea bread known as Barmbrack–the recipe that she penned so elegantly into her book. I had to include her recipe and at least a brief note about her. How could I not?

Q: There are so many exquisite details woven into each chapter. Who knew about that electric oven? Or how Ontario cheese gained fame, becoming an important export in the 19th century? Or the modern convenience of commercially prepared rising agents for baking? And the fate of apples over time–tell me about the apples.

Yes! Cheese was once Ontario’s second largest export commodity, right behind lumber. Ontario cheddar was world famous until 1952, when Britain cut off all cheese imports from Canada in order to rebuild their own cheese industry.

Apples, too, have an astonishing story. Here in North America, they were a survival food for settlers: used in cakes, pies, steamed puddings, apple butter, chutneys, applesauce, and, of course, cider. Suitable apples were barrelled in the autumn. Others were dried and used right through until the next crop ripened. The first apple orchards were planted in what is now Ontario in the 1700s. The humble but endlessly useful McIntosh originated here in Ontario, in the Saint Lawrence River Valley. During the 1800s there were 7100 named varieties of apples grown in North America. Over 6800 of those varieties are now lost and of the remaining varieties, Red Delicious accounts for 90% of all apples sold.[i] This staggering loss of biodiversity tells an important culinary history story all by itself.

Q: As a reader, I found the handwritten recipe cards moving; they reminded me of the recipes my grandmothers wrote out and gave me. These and other visual elements of the book are striking. The design is a central feature. What are the challenges of working with images as well as text, for you, the author, as well as editorial and commercial challenges?

Q: As a reader, I found the handwritten recipe cards moving; they reminded me of the recipes my grandmothers wrote out and gave me. These and other visual elements of the book are striking. The design is a central feature. What are the challenges of working with images as well as text, for you, the author, as well as editorial and commercial challenges?

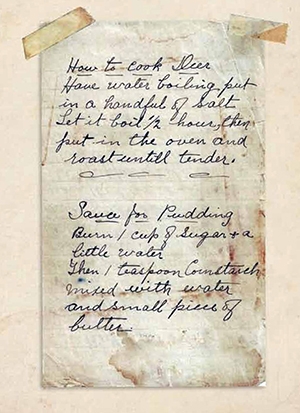

I absolutely love the handwritten recipes and tried to include as many as possible. In the 1800s and early 1900s women had so little. Paper was scarce. A poor household might only have a book or two. It’s been said that many young girls on the land learned both literacy and numeracy thanks to the family cookbook. And anyone lucky enough to have a notebook to fill with recipes used every scrap of paper in the book. Those that remain are now hugely important primary history resources. The pages are often full of household tips–medical cures and instructions for cleaning hats–mixed with recipes. There’s an example of this in Out of Old Ontario Kitchens where a recipe entitled, “How to Cook Deer” is followed on the same page by a recipe for a caramelised sugar sauce “Sauce for Pudding.”

Finding the images was a big part of my quest. It was like a treasure hunt searching out images of the era, but I wanted a book that showed how visually rich this topic is. There were all the usual permissions to be organized and, in some cases, fees to be paid. And including the images often meant chopping text–always a challenging task! Fortunately for me, both the publisher and book designer were a treat to work with.

Q: How much, if any, recipe testing did you do, given that the recipes are historical artifacts?

Actually, I trialled the vast majority of the recipes! I learned about and hunted down elderberries and butternuts and shagbark hickory nuts. I tracked down locally grown organic Red Fife wheat. I dried apples. I found a source for venison and cooked it according to the instructions in “How to Cook Deer.” What I learned was that pre-industrial food is fantastic. One of my favourite recipes is the dried apple cake. I’ve taken to cooking more and more pre-industrial food. I did draw the line, however, at the recipe entitled, “A Good Mode of Smoking Meat,” from The Canadian Economist 1881, which calls for a sugar hogshead (a very large sugar barrel) and “a considerable portion of dried dung.”

Q: Bring out the dried dung! What’s your next project?

Another food book. It appears I cannot help myself!

It might sound overly ambitious, but I want to disabuse the notion that food writing is somehow not real writing. Nothing could be further from the truth. Those early women food writers left us invaluable historical resources and their work often kept entire publishing companies afloat.

But even more to the point, when we write about food, we are really writing about humanity and community; about love and death and biological imperatives; and about the powerful connections and similarities between us. Food writing has been as undervalued as the actual work of food preparation.

Food stories are, after all, the real and fundamental stories of our lives.

[i] The Economist, “Banks for Bean Counters,” September 12, 2015.

Laura Rock Gaughan is the author of Motherish, a short story collection published in 2018. She lives in Lakefield, Ontario with her family.