Finding the Form with Sally Ito

By Sally Ito

I have a confession to make. When it comes to reading and writing, I’m a portmanteau sort-of woman. A jerrymander-er. One who fools with boundaries. I’m a cross between a statesman and a salamander.

When I read, I don’t often read whole books to the end. I read parts-of-books; I read off the internet – blogs, articles, FB posts. I read the newspaper, newsletters, church bulletins, backs of cereal boxes and jam jars. I read whatever I set my eyes on that is in print around me. Often that is stuff on my phone, but not only. There are signboards, labels, directions, warnings on paper, cloth, metal, plastic.

I am a flibberty-jibbet sort of reader. I Skip-to-My-Lou with words. Words like Mea culpa. I am a flaneur of les mots, strolling through the lines and alleyways of sentences on a page or on the screen, and I’m not very good at dedicating myself to a single genre as a writer or a reader.

I write and read This n’ that. Mixed prose, sometimes poetry. A fiction or a-non. That’s what I’m about in reading and writing. And I’m not ashamed to admit it. My name is Sally Ito. I have a reading and writing problem. Genre scares me.

Because, you know — it’s all about keeping it fresh.

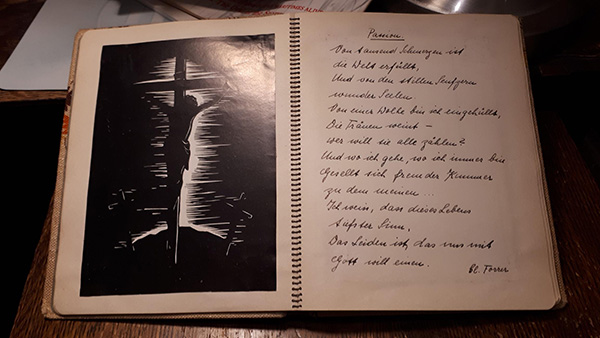

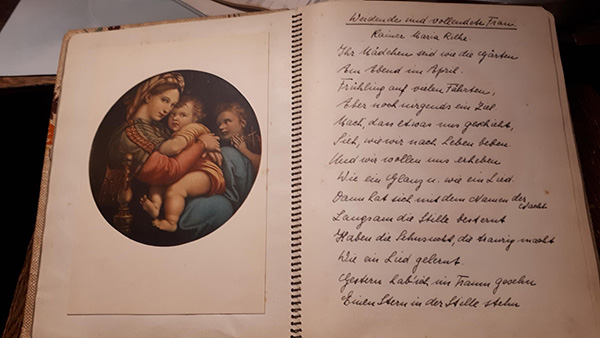

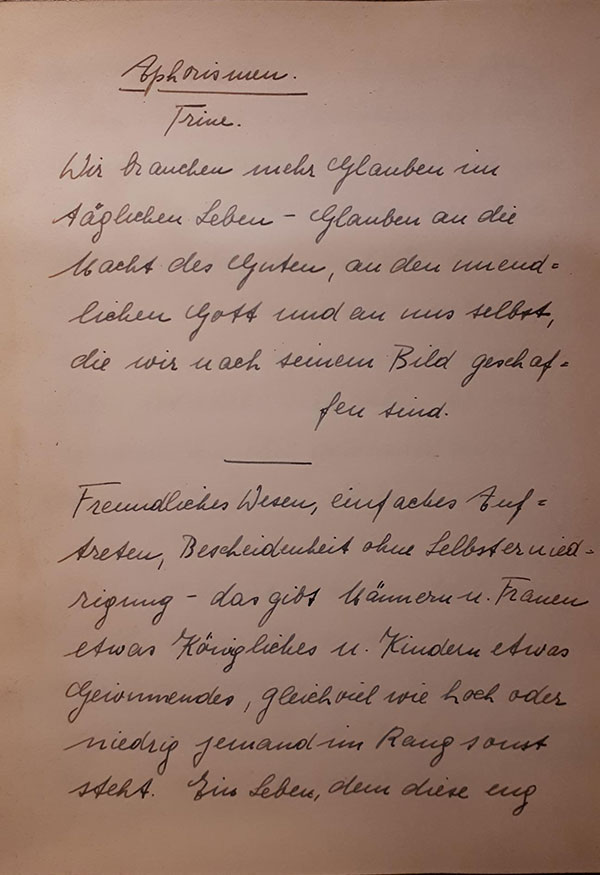

So, all this is preamble to tell you how I came to write the segmented essay in the recent issue of TNQ called Notes from Berlin: A Writer’s Baedeker. In November 2017, I went to Berlin. A lot of things were on my mind at the time. And Berlin, in its sneaky, uber-artistic way, was just the right rumble ground for me to record both the inner and outer spheres of my existence at that moment in time. The Notes from Berlin part of the title is literal. I kept a notebook with various jottings about my experiences in Berlin. At the same time, I was thinking about travel writing and about the excellent 19th century travel guides – Baedekers, as they are known – that the Germans produced for travelers.

Travel guides let you experience another culture in words of your language. The words are a bridge from one culture’s consciousness into your own. They allow you to compare-and-contrast the personal culture of your mind and body with the minds and bodies of others.

What Berlin showed me is that there is no monoculture — there is only and always intermingling and interacting, juxtaposition and association. The city affirmed in me what I always thought about what it is like being a certain minority in a certain place with other minorities trying to carve out an identity for oneself in words.

Words come in different languages, of course, and my recent obsession with translation made me aware of that. Translation made languages seem like creatures to me – creatures with temperaments and sensibilities.

What I said about writing and Berlin in English about Germans, Japanese and Japanese Canadians, Christians and Jews in Notes from Berlin was cumulative compilation of associated thoughts, ideas, and reflections of my experience in that city.

Notes from Berlin began as handwritten notes in a journal I picked up in a supermarket. Then when I transcribed the handwritten notes onto the computer, I began to organize them into segments that I hoped would associatively link to the next segment. When I finished, I sent out the essay to writer friends for feedback. It was interesting to see what they said. Most of them didn’t have trouble making the associative leaps from one segment to the next, but occasionally someone would say that a segment didn’t seem to fit or that it needed to be reworded differently to fit. Others wanted some other things explored in the essay that were not there. Of course, my writer friends knew me personally so they were able to relate to my telling of my travel adventures. But how would this essay fare with the reader who did not know me at all? For some reason, this is the real test for me, the writer. Do I in my writing interest you? Do my words grab you?

Ultimately, when I get a piece accepted for publication, I feel the answer is YES. And I rejoice and blush because it’s a bit like hearing the words ‘I love you’ from a complete stranger who does not know me from either Adam or Eve, Shakyamuni or Maitreya.

So herein ends the sermon with a quote from E.M. Forster: Only Connect! Only connect the prose and the passion and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its highest. Live in fragments no longer.

Photos provided by Sally Ito.

Photo by Stylite yu on Unsplash.

Sally Ito is a writer and translator who lives in Winnipeg. Her latest book, The Emperor’s Orphans published in 2018 is a personal myth that explores Ito’s cultural identity and formation as a Japanese Canadian writer.