Finding the Form with Ian LeTourneau

By Ian Le Tourneau

Birds occasionally take centre stage in my poems and many fly through in minor roles, on their way, perhaps, to find better habitat elsewhere (in other poets’ poems?). Starlings, chickadees, pine siskins have been my subjects; crows, pileated woodpeckers, red winged blackbirds, to name just a few, have flapped or soared through my poems.

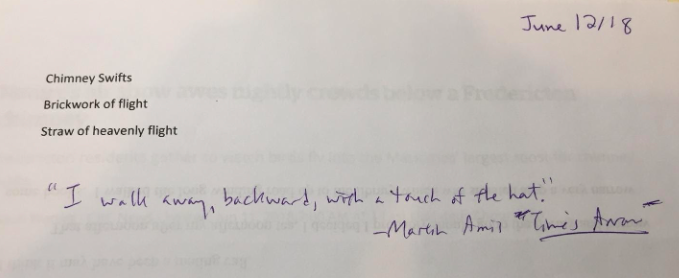

I find birds endlessly fascinating. So when I read a CBC New Brunswick article about chimney swifts (“Nature’s air show awes nightly crowds below a Fredericton chimney,” June 11, 2018) after hearing a feature on the local morning show, I knew I wanted to try to write a poem. And I made a start on June 12, typing a few initial thoughts. Not a very good start. Embarrassing, really. But I guess we have to push through the embarrassing to get somewhere hopefully not embarrassing (or in other words, bonus embarrassing lines and phrases to come below!).

The idea of a mass of birds flying into a chimney struck me as a potent image of an industrial reversal. And for some reason I thought of Martin Amis’ Time’s Arrow, which I must have spent some time leafing through and then wrote the quotation down. The “touch of the hat” of the Amis quotation, to me, strikes me now as a fine gesture from the birds.

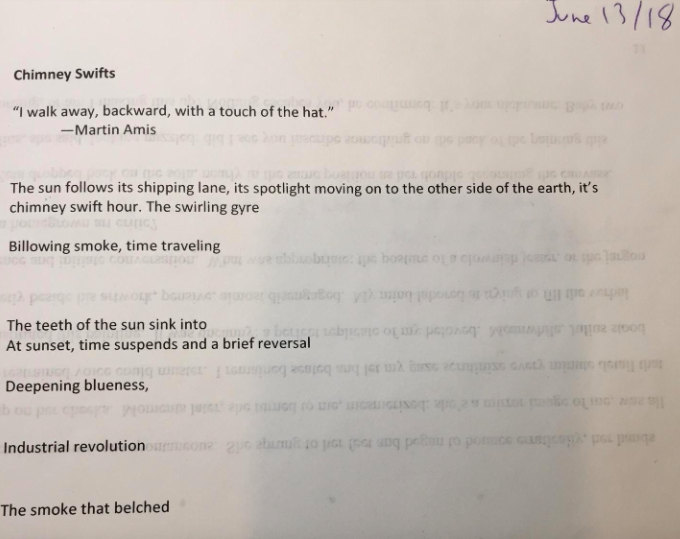

In my next drafts I started to try to find some industrial language that would set up the reversal, which is clear from “shipping lane,” “teeth,” and “smoke that belched.”

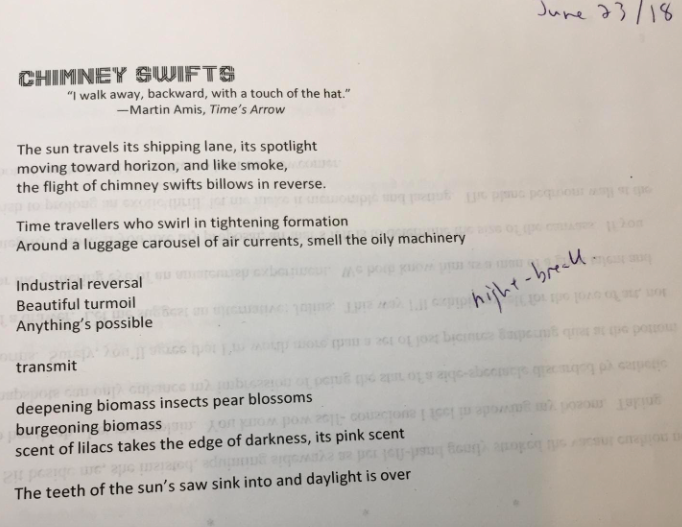

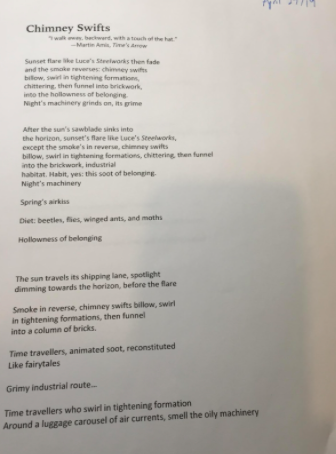

Ten days later, I came back to the poem, and it started to become a bit more cohesive. You can see below that I may have found the progress frustrating as I was clearly noodling around by playing with the font of the title. Also, the image “luggage carousel of air currents” which appears in the next few drafts was eventually pilfered and subsumed into another poem.

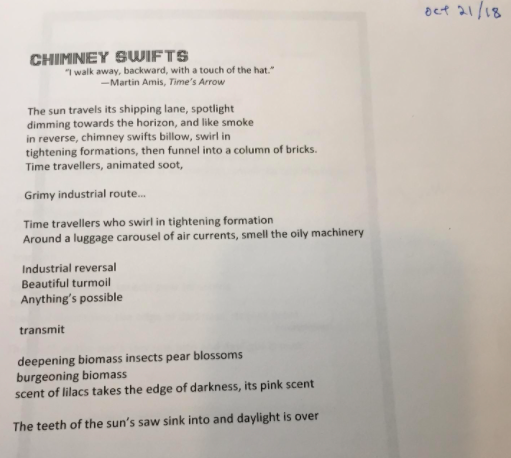

At this point, I didn’t come back to the poem until 4 months later at which point I added some more detail that I must have been hoping to incorporate into the poem. And you can see some of the eventual shape coalescing.

Then 6 months later I took another run at the poem. I had recently been to the AGO on a trip to Toronto and saw an exhibition of paintings that documented the industrial revolution so I had the idea – which never stuck – to begin with the dramatic imagery of Maximilien Luce’s “Steelworks,” which was one of the more striking paintings I saw. (Sidenote: I also happily attended my first Blue Jays (more birds!) game with Daniel Renton and Daniel Tysdal.)

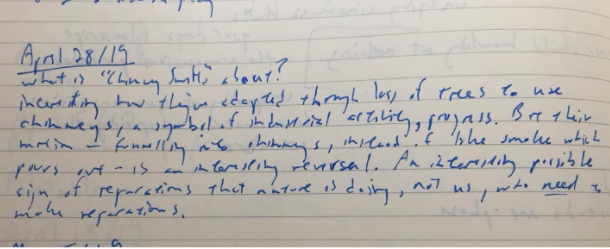

Then the very next day, perhaps sensing that the poem needed focus, I wrote the following in my notebook:

When I took up the poem again, a month later, while I was staying for a week at the Elizabeth Bishop house for a writing retreat, the next two images show a few printouts of some progress, as the file remained open on my computer for a few days. By the end of May 22, the poem was in its final form (as printed in TNQ).

As for the actual form — a blank verse sonnet: I am obsessed with sonnets. Robert Lowell’s sonnets (History) are particular touchstones that I re-read every couple of years. So I basically start every poem as if it’s going to be a sonnet. It seems like a natural limit: I usually say what I want to or need to say in 14 lines or so. It’s a convenient unit of thought. (I also obsessively date every piece of paper I write on… ever since I read somewhere that TS Eliot admonished a younger poet for not doing so.)

Ian LeTourneau is the author of two chapbooks, Defining Range (Gaspereau) and Core Sample (Frog Hollow), and the full-length collection Terminal Moraine (Thistledown). He lives in Fredericton, NB.

Photo courtesy of Josi Ribeiro