Notes From the Wild: An Account in Words and Music of R. Murray Schafer’s And Wolf Shall Inherit the Moon

Transformation: What is the purpose of art? First, exaltation. Let us speak of that.

— R. Murray Schafer

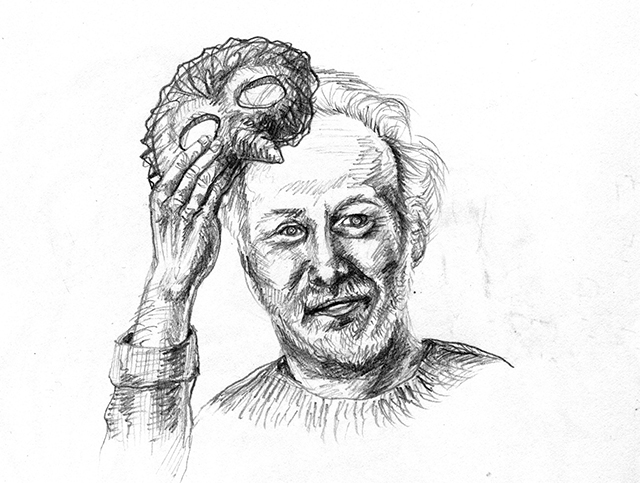

If exaltation had political currency, would there be more poets? Or clamouring in the streets for radically optimistic works like A Gathering of Waters, Jazz on Wheels, and Ballroom Dancing? The non-utilitarian nature of the arts disrupts the tendency to reduce activism to mere goal-directedness if only because empathy, abundance, shock, beauty, exaltation—whatever art awakens or stirs—is hard to attain, harder still to measure. R. Murray Schafer’s The Wolf Project serves as a powerful antidote to scepticism about art’s ability to reorder the world. But if myth and ritual can be tendered for harmony in the cosmos, it’s a story only an insider can tell. Who better than Rae Crossman, the man who would be Wolf?

If exaltation had political currency, would there be more poets? Or clamouring in the streets for radically optimistic works like A Gathering of Waters, Jazz on Wheels, and Ballroom Dancing? The non-utilitarian nature of the arts disrupts the tendency to reduce activism to mere goal-directedness if only because empathy, abundance, shock, beauty, exaltation—whatever art awakens or stirs—is hard to attain, harder still to measure. R. Murray Schafer’s The Wolf Project serves as a powerful antidote to scepticism about art’s ability to reorder the world. But if myth and ritual can be tendered for harmony in the cosmos, it’s a story only an insider can tell. Who better than Rae Crossman, the man who would be Wolf?

Did You Chant the Sun

- did you chant the sun

- to its rising

- did you take its spear

- in your eye

- did your blood flow quicker

- when you danced in dawn

- did you throw your arms

- to the sky

- oh, we’ve lost the sun

- the old ones knew

- our tongues forgotten

- the fevered cry

- our feet must find

- the ancient dance

- or the flames in our hearts

- will die

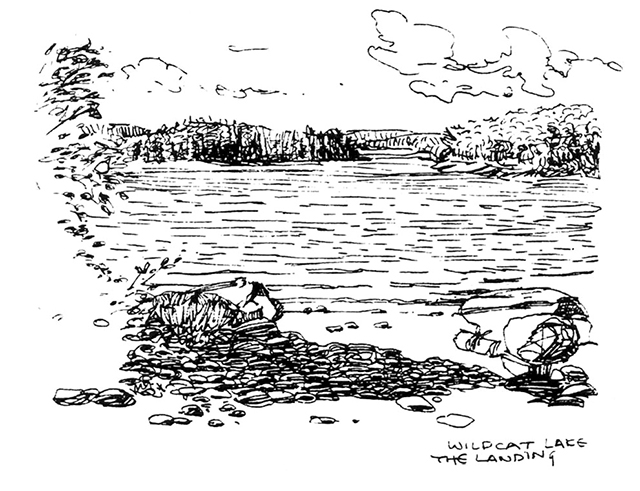

Morning,Wildcat Lake: a white-throated sparrow sings high in a balsam fir. Two otters swim close to shore, curious heads poking out of the water, listening. The notes of a clarinet rise and fall, delicate tendrils of sound swirling with the dawn mist. An alphorn, deep and resonant, calls in response from somewhere on the far shore.Through the mist, the heavy wing beats of a loon cut through the air in a steady rhythm. I wait in anticipation, exchanging expectant glances with my companions. Ascending over the tree line, the ever-heralding sun sets me ablaze with wonder.

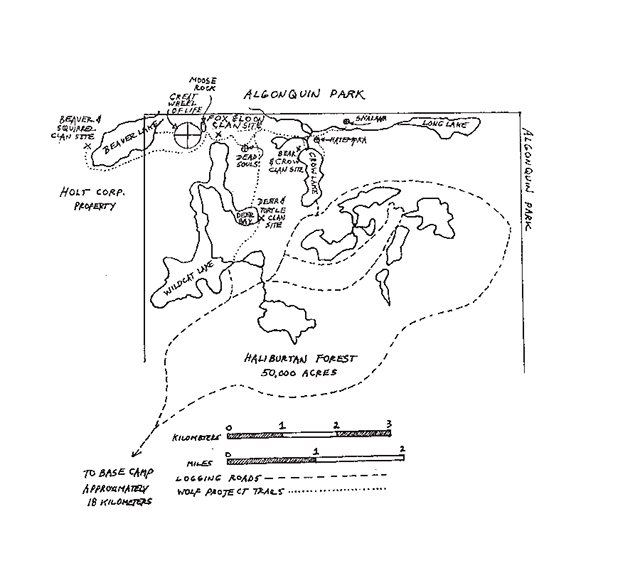

Mornings like this have animated my summers for over fifteen years now, as I have fired my sense of mystery and marvel with fellow participants in R. Murray Schafer’s And Wolf Shall Inherit the Moon. The Canadian composer’s unique, collaborative work is an annual pageant involving musicians, actors, dancers, artists and storytellers who create musical drama in the Haliburton Forest and Wildlife Reserve, on the edge of Ontario’s Algonquin Park. This is music theatre like no other: the stage is a moose meadow, a rock strewn gorge patterned with moss, a raft assembled from rugged cedar driftwood, or a quiet forest pool, fringed with cardinal flowers. The lighting: dawn through filigree of pine, intense noonday sun on a burnished lake, flickering campfire flames, or a million stars. Flute music accompanies birdsong. A trombone echoes across the bay. Is that wind in the tamarack or an ethereal voice singing sibilant notes of sorrow?

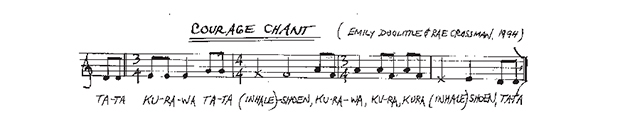

How do you find out about the performance? Is there a poster? Where can you get tickets? Well, there is no media blitz, and there are no tickets. Instead, you hear from a friend of a friend who invites you to a mask-making workshop. Or a colleague at work takes you to a new music venue where you meet a dancer who speaks about an inspiring work that has her dancing in the rain on slippery logs. Intrigued, you attend a few planning meetings, find yourself making your own mask, imagining dance movements—before long you’ve packed your tent and gear and driven to a remote forest access point where you rendezvous with others who have travelled great distances for the yearly gathering. You canoe across a lake, clamber over a beaver dam, and hike for two hours before a startling costumed figure leaps from behind a rocky outcrop and guides you to a natural amphitheatre in an aspen grove. Be ready. You may be asked why have you undertaken such a journey into the forest. What do you hope to discover along the trail? Are you prepared to be transformed? Suddenly you are part of the encounter. You are challenged, and in response you offer the strange chant you learned from your companions as you travelled through the woods.

The oral token works; and you gain entry into a mysterious realm of story, music, dance and ritual. The experience is participatory; you become one of the performers. From your pack you pull out your mask, slip into your costume. Soon you are beating out the rhythm with your frame drum.You have come to take part in a hierophany, a sacred drama.

The archetypal storyline draws from deep wells:Theseus and Ariadne, Beauty and the Beast, the Ojibwa Star Maiden, and others.This particular “telling” unfolds over the course of an eight-day sojourn in the forest, as you learn at the campfire, on the portage trail or in the bow of a canoe, the legends of Wolf and the Princess of the Stars—the estranged male and female counterparts of the fabled story. In mythic times past, Wolf lashed out at the Princess of the Stars, who had fallen from the heavens while listening to his mournful howling. She fled to a lake to bathe her wounds—Wildcat Lake, the very lake where we camp—but Three-Horned Enemy dragged her under water and the stars were lost in the waves. Sun Father released her, but now Wolf must go in search of the Princess in order to restore harmony to the world, a harmony destroyed by humans as they plundered the land. Wolf has searched through a thousand lands in a thousand incarnations, sometimes as Anubis, sometimes as Theseus, looking for the thread of her love to deliver him from his labyrinth of anger. He has never found her in all his wanderings, and he rages like Fenris, the apocalyptic wolf of Scandinavian mythology, ready to tear up the world.

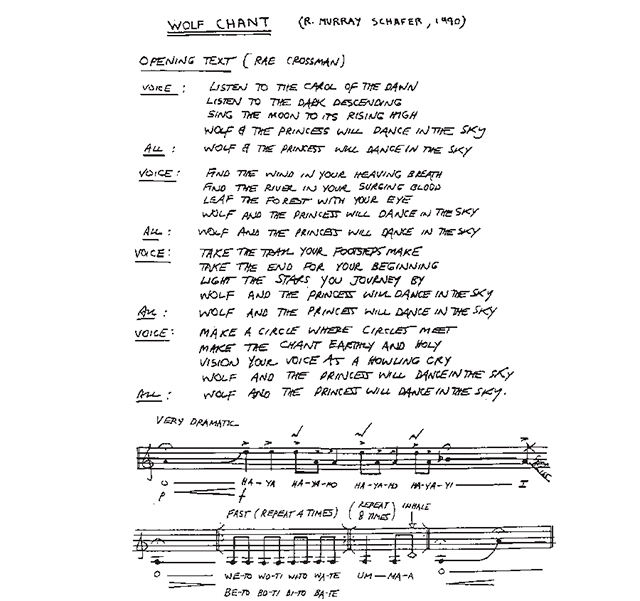

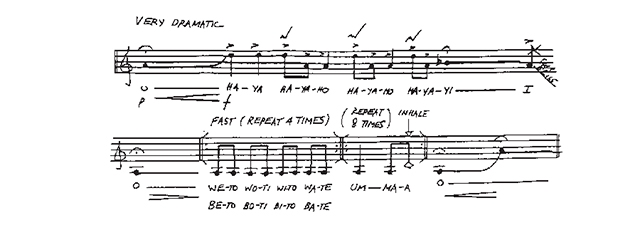

But now we have a chance to bring them together in joyful union. We have made the journey and prepared the sacred drama to summon Wolf and the Princess. Will they come in answer to our drumming, to our chanting? We cannot fail. The costumes, the music, the potent words. If we do the ritual as befits the urgent need, Wolf and the Princess will dance in the sky!

Two parallel strands: the human journey into the wilderness, with its challenges of weather and terrain, in order to mount the theatrical ritual, and the larger-than-life mythic story of Wolf in search of the Princess, with all the interventions of Three-Horned Enemy, a shapeshifter who is a catalyst for change. The two quests, ancient and modern, converge in the transformative experience we call The Wolf Project, something much more than the bare bones script of And Wolf Shall Inherit the Moon. The human drama requires a co-operative spirit to overcome physical obstacles, yes, but also to jointly write script, develop choreography in situ and respond to the unexpected. Quick—the trombonist has wrenched his leg in a fall along the riverbank. Get the wilderness first aid book; we might need to make a splint! And who will play his part in the score? There’s a trumpeter in the next campsite at Crow Lake. The music will have to be transposed, then a volunteer deliver it and the costume—two miles away—and return again by nightfall. A thunderhead is gathering in the west; Three-Horned Enemy has leapt off the pages of the manuscript and into our lives.

Music is integral to The Wolf Project. We rise each morning to an aubade played over the water. The notes of a clarinet swirling with the dawn mist. We retire in the evening listening to a nocturne, an aria sung from a canoe out on the lake. Canoe and soprano silhouetted in the moonlight, a distant loon calling in response. The rhythm of nature reflected in the rhythm of the work. Schafer takes music out of the concert hall and into the wild places where it was born. And not just music, but art out of the galleries and into meadows, grottos, and sun-dappled forest swales, theatre out from under the proscenium to a raw vitality under a rainbow or the northern lights. He shifts the context, and in so doing makes us look at lakes, rocks and stars differently, just as we hear music differently, regard art in fresh ways, and respond to theatrical performance with a new sense of relevance.

For Schafer, art is a way to recover the sacred,“to sense the divine in all things.” He deplores the current desacralization of nature: “If a tree is sacred, you think twice before cutting it down, and clear-cutting is out of the question.” To restore the mystery of the sun and the moon, begin by dancing at dawn, singing at sunset and mediating at moonrise. If it rains, find a blessing in its rhythm instead of a reason to cancel. And instead of shaping nature to a human purpose, prepare to be changed by the natural forces that might offer up wind, hail or an evening of golden light and the fluid notes of a carolling thrush deep in the forest. Prepare to be changed by the “holy theatre” that surrounds you.

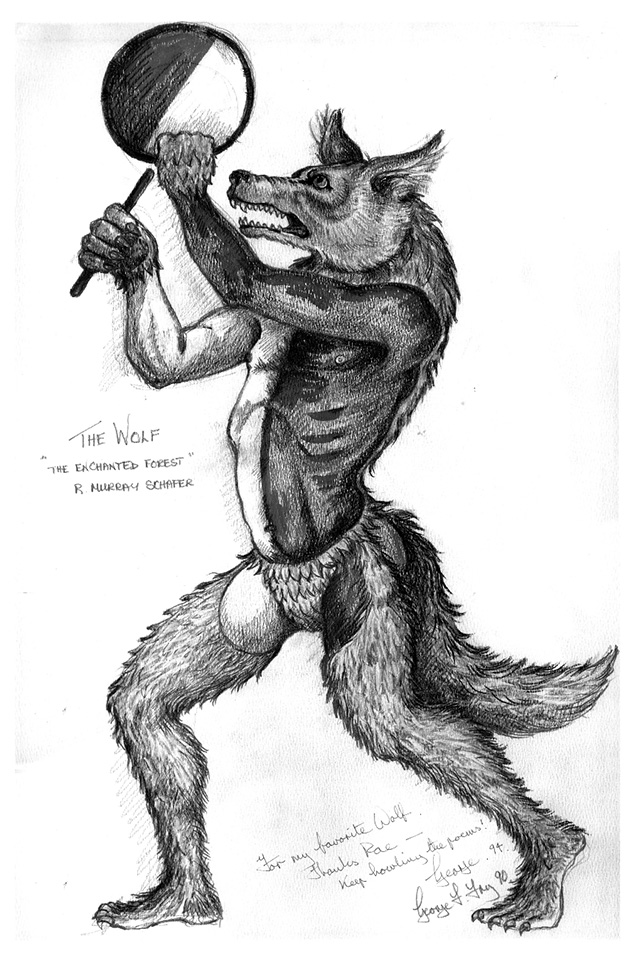

And Wolf Shall Inherit the Moon is the epilogue to Schafer’s vast Patria cycle, a 12-part work that includes The Princess of the Stars, The Enchanted Forest, Ra, and The Palace of the Cinnabar Phoenix. The themes he explores are both mythic and contemporary, with an urgent emphasis on our relationship to the environment and to each other. Together, these works are part of what Schafer calls Theatre of Confluence. Using the metaphor of rivers flowing together into a larger, more powerful current, Schafer merges all the arts; no one medium is predominant over the others. Perhaps this ideal is most fully realized in Wolf; for while Schafer has provided the central outline, he has also invited others to share in the creative process. Musicians contribute their compositions, dancers provide choreography, actors write scripts, and storytellers flesh out the original story with additions and variations of their own. In Schafer’s own words, what the participants are creating is “co-opera.” Indeed, people come from afar to do just this. From British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario and Nova Scotia, from Indiana, Vermont and New Jersey. Even a contingent from Brazil and Portugal makes the annual pilgrimage to the Haliburton Forest in search of Lobo e a Princesa. But participants do not simply attend as experts in a particular area. Dancers also sing, musicians also act. A soprano portages a canoe. A composer cooks over a smoky fire. Boundaries are blurred. New roles are explored. Many are not performance specialists at all.The idea is to experience and grow in new areas, whether in music, acting, or perfecting the J-stroke. There is no passive audience expecting to be entertained; all become participants in the creative and collaborative experience. And Schafer— that is, Murray—is there too. Over seventy years old now, he hikes the trails, sets up tarps in the rain, and howls the Wolf Chant with wild, inspiring vigour.

Murray is interested in the transformative power of art not just as an abstract idea but as real change that engages muscles, emotions, intellect, and spirit. Transformation that gets honed into action. While Murray does write music for the orchestral hall, he laments a frequent complacency that may leave an audience essentially unchanged: two hours of genteel listening rarely results in a shift of perspective, an alternate approach, or a new resolve. But leave behind the air-conditioned theatre, journey down a bush road, portage a canoe, paddle against a headwind, carry a pack along a trail that skirts the edge of a marsh where a heron silently fishes, and then, muscles sore and senses alert, find yourself listening to a small choir of voices hidden in the alders . . . now that can elicit astonishment, that can engender fervour, and prompt you to produce your own artistic creation in response.

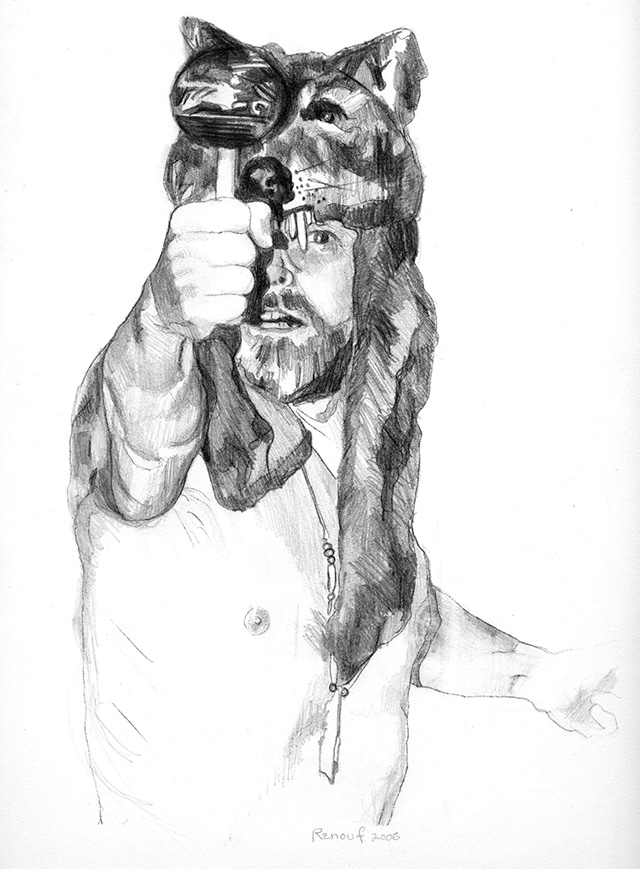

Ideals are hard to maintain, but Murray demonstrates his commitment to art as a generative process by giving people countless opportunities for growth. I am a case in point. Before joining The Wolf Project, I knew virtually nothing about music, couldn’t carry the simplest tune, had never acted. What I did have, along with bush skills, was poetry. Poetry as a living experience, poetry coming out of the oral tradition to be shared around a campfire, to be offered as grace before a meal, or hurled against the wind to sustain a long paddle down a choppy bay.

On the strength of the poems that welled out of me in the early days of establishing The Wolf Project, Murray suggested I try the role of Wolf. He could have looked for an experienced actor, but true to form, he was willing to take risks for the sake of his artistic intention: transformation. As a result, I have spent over a decade of summers loping along forest trails with wolf mask headdress, bone necklace and frame drum, chanting and howling. Drawn by the scent of the sacrificial stag, I have come to a moose meadow and encountered a strange, alluring ritual. Full of rage I have come, snarling, canines and incisors snapping, ready to destroy the entire assembly, only to discover the Princess of the Stars waiting for me. How did I get here? Panting and trembling, nostrils flared, listening to her calming, high soprano voice, I succumb to enchantment.

The Theme Story as conceived by R. Murray Schafer:

And Wolf Shall Inherit the Moon

In the beginning humans and animals were the same, for humans were also animals. They believed they were descended from the gods, who lived in the heavens as planets and stars. They shared the world together and all spoke the same language. The symbol of their harmony was the Great Wheel of Life, which contained all creatures as well as trees, plants and stones in a harmonious cycle.

But then humans began to develop the idea that they had ascended above the animals, were therefore their superiors, and began to invent another language that the animals could not understand in order to deceive them. They also took all the best land for themselves, building fences around it and killing all intruders.

The animals met together in council to discuss the situation. Each spoke in turn but the last words were given to Wolf and Bear who were the strongest of all the animals and who loved free space the most. Wolf was for declaring war on man, but Bear counselled restraint and arbitration. After a full discussion the animals decided to accept Bear’s advice. Wolf left the meeting angrily, swearing that henceforth he would live alone in the deepest part of the forest. Each night he could be heard howling and his howls sent shudders of fear through all the animals as well as humans.

One night the Princess of the Stars, hearing Wolf’s mournful howling, dropped out of heaven into the forest. She hoped to reconcile him with the other animals, but Wolf lashed out and wounded her. She fled to a lake where she was captured by a monster called Three-Horned Enemy. The Dawn Birds carried messages of the Princess’s predicament to Sun Father and he descended to the lake. All the creatures were in awe of Sun Father when he descended to earth. He commanded Three-Horned Enemy to release the jewelled crown of the Princess and return it to the sky. He told the Princess to remain on earth until her mission was accomplished. Then he sent out Wolf to search for her. He would travel throughout the world in many guises until, through her love, his rough instincts could be curbed. Then harmony would be restored to the world; the Princess’s spirit could return to heaven and Wolf himself would inherit the moon, becoming its divinity. Wolf has been travelling the world for centuries, sometimes in the form of a man, seeking the Princess, whom he calls Ariadne, because it is she who holds the thread of his deliverance. These are the adventures recorded in the Patria cycle. Although Wolf and the Princess seem always to be moving towards one another, they never quite meet; and thus the world remains disjointed.

All this is evident to the animals, though humans, who have forgotten their myths, are ignorant of it, and believe that harmony, if it is to be achieved at all, will result from improved human management.

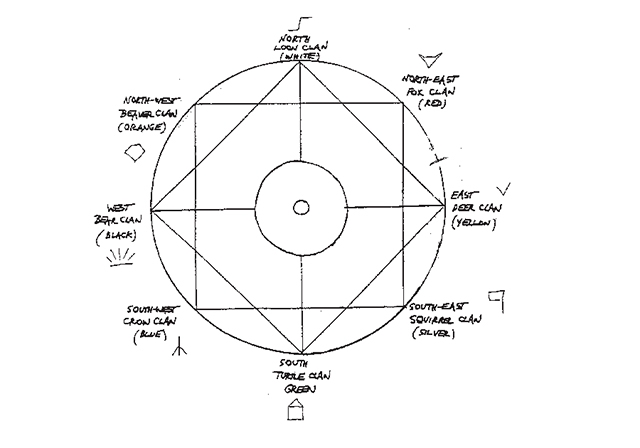

The animals, however, have decided to attempt to restore harmony by a different strategy. They will take some humans into the forest, teach them the ancient myths and incorporate them into a ritual that will bring Wolf and the Princess together at last. The participants will be divided into eight animal clans: Deer, Squirrel, Turtle, Crow, Bear, Beaver, Loon, and Fox. Each clan will camp in the forest for several days preparing a portion of the final ritual. Each clan will make its own costumes and masks, will be taught the clan stories and will learn the clan chants and dances. At the end of the week all the clans will come together to form the Great Wheel of Life and to enact the ritual designed to unite Wolf and the Princess. If this succeeds, the great turning point, awaited for centuries, will be passed, a spirit of sacredness will again possess the earth and gods will illuminate the heavens.

The Haliburton Forest by Jan Buley, Beaver Clan

Peter Schleifenbaum oversees and nurtures the Haliburton Forest—a 60,000 acre privately owned tract of wilderness. As the first certified forest in Canada, the entire setting is managed to internationally recognized environmental standards: rather than harvesting the best wood, foresters remove ageing or low quality trees, thereby making the forest healthier in the long run. In addition to providing a “living wildlife classroom” for University of Toronto forestry students, the forest includes a wolf centre, logging museum and forest canopy tours; for the past fifteen years, Schleifenbaum has also generously allowed The Wolf Project to use the Haliburton Forest. Here a fallen hemlock tree can become a puppet theatre. A discovered cave is an explosive acoustic space for a double bass dialogue with a storyteller. Rocks talk. Rain-clouds tease and swirling winds pull at masks and costumes. Ultimately, we are guests in Schleifenbaum’s paradise—and the Haliburton Forest is our intriguing, unpredictable host.

Wolf Music: The Recording

Cameras and recording equipment are not part of the Wolf Project. You can’t buy a video of the piece and watch it on your flatscreen; you have to experience the mythic drama from the inside. However, on a separate occasion outside of Wolf Project time, a few selected pieces were recorded by CBC Radio. Before dawn, under the stars, producer David Jaeger and recording engineer David Quinney with Steve Sweeney canoed out into Wildcat Lake to various pre-set floating platforms. Adjusting the equipment in the dark, they recorded the musicians playing on shore in the lambent glow of morning. Rain, too, became part of the morning music and the recording, as did a jet plane in the final bars of the delicately concluding aria. All part of the complex soundscape.

A co-production of CBC Radio and West German Radio, Wolf Music was broadcast on the CBC radio program Two New Hours. Thank you to the CBC for allowing us to reproduce that recording; we encourage you to listen to Schafer’s music as you travel into the forest with Wolf.

Wolf Music

- Tapio for alphorn with echoing instruments

- Aubade for solo trumpet

- Sun Father: Earth Mother for solo voice

- Aubade for solo clarinet

- Nocturne for solo flute

- Nocturne for solo trumpet (and obbligato voice)

- Nocturne for solo clarinet

- Sunset for natural trumpet

- Departure for trumpet and echoing instruments

- Ariadne’s Aria for solo voice

-

- R. Murray Schafer (music, text, narration)

- Michael Cumberland (alphorn, tuba)

- John Dewhirst (trombone)

- Wendy Humphreys (soprano)

- Stuart Laughton (trumpet, cornetto)

- Tilly Kooyman (clarinet)

- Ellen Waterman (flute)

Arrival: Haliburton Forest and Wildlife Reserve

When I first heard about The Wolf Project, the multiple strands of mythology, dance, mask-making, story-telling and pageantry immediately enticed me, but I was doubtful about one thing: an eight-day camping trip with sixty-four people in the wilderness. Eight clans of eight. Despite the charm of the musical number, why would I want to go into the woods with sixty-four people? I went to the woods to get away from people. Besides, I was not the gregarious type. How would I fit in?

I’ve driven up with Tilly, a clarinettist and founding member of the project. We pull the car, crammed with packs, paddles and instrument bags marked “fragile,” into the gravel parking lot of Base Camp and immediately recognize the familiar vehicles: Doug’s truck, two canoes on top, trailer of canoes behind, Annette’s old style VW Microbus camper fromVermont, Neal’s station wagon with a double bass in the back (how does he fit that in a canoe along with his family’s gear?) and Helen’s car with the iconic Bluenose license plates from Nova Scotia. Animated greetings all around, hugs and kisses on both cheeks. This camaraderie did not come naturally to me in my first years of Wolf, but I don’t have the same unease now. There’s Barry! Like me, he is a member of the Bear clan; let me give him a bear hug: “Nya, Nya Nya.” And of course there are new people to meet. Jarvis and Roewan who drove from Manitoba, Eric from Ottawa, and Elaine’s newborn. Listen! Isn’t that a Harley? Jan and David are just rumbling in from New York.

This yearly renewal of friendships and shared purpose, for many of us, has shaped a significant pattern in our lives. It’s August; it’s Wolf. Despite busy schedules, we are bound by a commitment to this annual undertaking. Throughout the year, too, logistics planning, script writing and costume making keeps us in loose contact. Fran, a long-time member, once observed that Wolf is a “social experiment.” Her comment reveals something I had originally overlooked in my misgivings about wandering around the woods with dozens of people. Wolf is not just a music drama set in the forest. What’s important is how the work is created—the spirit of co-operation and the fundamental relationship to the forest environment. The work’s overall theme addressing the need for harmony requires a social dimension, and the framework of clans creating and presenting theatre for each other supports that social cohesion.

But what about the environment? Heading into the woods with dozens of people means that we must thrive there in community, and not destroy the very thing we have come to celebrate: the natural world. To reduce the impact on the forest we divide the clans into four campsites joined by interconnecting trails: Fox and Loon at the head of Wildcat Lake, Deer and Turtle in the shelter of Deer Bay, Bear and Crow on the shores of Crow Lake, and Beaver and Squirrel at the most remote site, Beaver Lake. Not exactly “no impact camping,” but we do strive to make as minimal disturbance as possible and to integrate our theatrical creation respectfully into the landscape. Wolf isn’t only about changing attitudes towards nature; its grand sweep seeks to change the world. A tall order, but suitably mythological. On a smaller scale Wolf seeks to change the participants, and we mustn’t get too smug. After all, we drove up here with our Kevlar canoes, nylon tents, Gortex jackets and technical underwear. When we depart, it’s our awareness and our attitudes that we want changed, not the shoreline where we camped. Let’s see how we do. One last check of the canoe ropes, and we pull out of Base Camp, heading down narrow bush roads to the landings.

The road splits and our group turns toward Crow Lake. The farther into the forest we go, the more the road deteriorates. The last 500 yards is a portage to the water.The scooped thwart of the canoe rests comfortably on my shoulders, but it’s still a heavy load and I push myself to make the shore without stopping. Then again, I remember that the really significant weight on a portage is the weight of everything I’m not carrying—payments, files, reports—and just the thought makes the load lighter.

wildcat landing

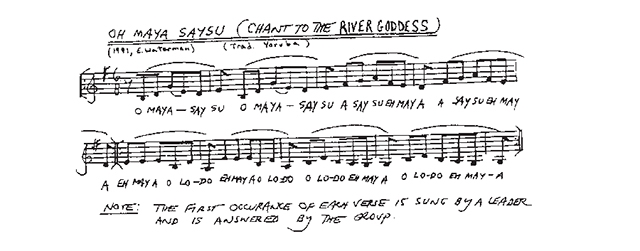

After most of the gear is loaded, we make for the campsite across the lake against a rising headwind and the threat of rain. Although the crossing is a relatively short fetch, we encounter a mosaic of whitecaps, grey water and trailing foam. Just enough to lend an edge. Someone from an adjacent canoe starts up a chant to keep the paddles in rhythm, a call and response. It’s traditional Yoruba from West Africa, and we sing it with gusto half a world away.

Approaching the shore, we eye a tall, masked figure clad in loincloth standing on a rocky point. Around his neck, a string of shells, feathers and cones. A long alphorn sweeps down from his mouth to the open bell at the edge of the water—Tapio, a Finnish forest spirit, greets us with sustained notes carried by the wind. We are welcomed to the forest; our city life already seems far behind.

Get the tents up quickly, the sky is darkening. Marta will need help; she’s never camped before. The seed camp crew, Jennifer and Michael among them, already have the kitchen tarp set up in preparation for our arrival. They’ve been here days already—have food laid in, firewood gathered, water filtered, a latrine dug.They’ll make supper while the rest of us settle in. What—no tent pegs! How did I miss that on the checklist? I’ll have to improvise with kindling. Emily’s gone back solo in a canoe to get the rest of the gear. Wind’s up stronger now; it’ll be a struggle for her to return. But maybe these clouds will blow over without us getting wet. Damn, there goes a grommet in the kitchen tarp! Need to get on that right away. Listen to the wind high in the treetops—imagine a chorus of voices like that, thrashing rattles, swaying back and forth.

Too risky for an open fire. Looks like Jen and Michael have gone for the propane option. Other helpers arrive at the kitchen. The chore list gets passed around, and I sign up for dishes. That means I have time now for a swim before we eat. You know, I think we’re going to dodge the rain.

First Evening

Evening brings an unexpected coda of calm. The front drives off the dark cumulous and allows slanting rays of golden light to set the cedars on the opposite shore aflame.We attend to the vagaries of weather closely here, note shifts in temperature, remark on the quality of light, and in turn our powers of observation seem quickened. As the sun sets in a roseate glow behind us, we come to the lake’s edge to watch another aerial performance: the twilight choreography of bats.

Darkness falls and someone calls for the fire ritual. In the fading light, we respond:

The spirit of Shapeshifter presides over the lighting of the evening campfire. After the wood and kindling have been prepared, all form a circle around the fire pit. Rattles beat a steady count of four in eighth notes.

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

Open to second position plié turned out with arm in second position palms out to partners on either side. Follow with hand flame gesture for count of four.

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

Close with feet parallel, straightened legs clapping once low and once high.

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

- Chic, chic, chic, chic,

Repeat three times, followed by improvisation for flame segment. Repeat until fire is started. All blow on fire with hand gestures.

This first evening fire is time for the theme story to unfold, the story that sets the context for our labour and play. I slip back to my tent to get into costume: mask with rugged, exaggerated features, long black tangled hair, bear skin robe (faux fur), necklace of teeth (fimo), and a stout rattle. Wordshaker, an itinerant storyteller and poet who visits the clans, emerges. Quietly, I steal through the darkness and make my way back to the fire, where I wait in the shadows. When someone adds a dry piece of wood to the fire, spruce stars explode in the flames. I am summoned—arm raised high, I enter the circle of light, words and rattling syncopated.

- rattle of seeds

- and shards of bone

- above the voices

- above the flames

- the wordshaker

- speaks

- in the feather quiet

-

smoke is a story

- told to the clouds

- the wood is on fire

- with the telling

- the river is a story

- told to the sea

- the rapids are tongues

- of frenzy

- the rock is a story

- the wind and the stars

- the hoof of a deer

- leaves a story in the moss

- and the snake

- sheds its story in the grass

- the beaver slaps an ending

- dives and disappears

- but the ripples tell where it was

- stories are circles of remembering

- stories are eyes and ears

- and voice

- a rattle

- in the throat of living

-

rattle of seeds

- and shards of bone

- above the voices

- above the flames

- the wordshaker

- speaks

- in the feather quiet

I tremble the rattle at my side. No one moves.The gateway to stories now opened, Wordshaker begins the sorrowful story he is compelled to tell.The words resonate in the still evening. They fill the night, not just around the fire but also across the lake, reaching deep into the darkness.

- who howls in the forest so forlorn

- who howls the stars to fall, the moon to mourn

- who howls the heart stopped, the flesh torn

- who howls in the forest so forlorn

- once talon and paw

- hoof and hand

- all shared the same songs

- deer and fox

- crow and turtle

- bear and human

- all sang together

- in the great wheel

- the circle of our lives

The story, like the smoke, curls up from the fire like an apparition. Fabled figures move among us: Shalana, leader of the human clan in the time of harmony, and Haetempka, a medicine woman, his companion. But then, discord and destruction. Humans claim pre-eminence above all other creatures. The song has gone out of the land, says Shalana, and disappears. The humans are leaderless; anarchy reigns.

On this first night, each of the four different sites will hear various versions of the theme story. Sometimes it’s told in poetry, sometimes with puppets. Perhaps it will be danced. Always the same strife: Wolf for war; Bear for peace; Humans for all they can get for themselves. And always the same counsel: we must gather all the clans on Great Wheel Day and enact the ritual to bring Wolf and the Princess together. This is our task—to restore harmony to the world.

This night of reunions, introductions and stories ends a long day of travel. We have left behind our familiar world, sought a new landscape, and embarked on a mythic adventure. As the fire dies down and our eyes adjust to the dark, the silences grow longer. Someone suggests it’s time for the nocturne, which will close the day and mark the end of talking in camp. From a nearby rocky point, a horn, mellifluous in the still air, sounds its liquid notes across the lake. As the last strains fade, and the echo diminishes, we sit in silence around the vermilion embers. Only the night sounds of the forest. Peeps, chirps, unknown calls. A wood-boring beetle sets up a regular rhythm. Now a beaver splash! And another! One by one, we quietly make our way to our tents, attuned to enveloping sounds.

Soundscape—the word was coined by Murray some forty years ago to describe the acoustic environment. Entering with awareness into that environment, respecting it, responding to it body and soul—these are some of the reasons for our journey. This sonic attentiveness is part of the change we are actively cultivating. Deep listening. Deep living.

Sleep will come quickly after an exhausting day. All our muscles are calling for rest, but just at the edge of somnolence, we hear arousing yips and yelps. The coyotes can’t be very far away, but our attention is short-lived, and we finally submit to the gentle, hypnotic snoring in the adjacent tents.

First Morning

Drumbeat

I’ve been drifting in and out of sleep since the aubade: trumpet and voice inspired by nuthatch song. Male and female a tone apart. The drum calls us to the morning ritual at the edge of the lake. Out of the warm sleeping bag and into cold boots. We walk in silence, greeting each other on the trail with only hand signs: claw of bear, wing beat of crow. The ferns, heavy with dew, are beautifully arched. Someone on the far point is doing Tai Chi.

Drumbeat

The trail rises out of a hollow filled with deadfall balsam to bare rock that slants down to the lake; two tall white pines on either side of the gathering area frame the scene. Several people have already taken up positions, looking east across the water to the silhouetted tree line in the distance. The light radiates in a soft aura.

Drumbeat

As the sun rises above the trees, the drummer beats a series of sixteenths and turns toward the gathering. The drum stops and all clan members form a circle facing east, arms raised forward towards the sky, palms up. Fran Slingerland offers her words, the first of the morning:

- East

- springs to wake the breath

- to charge the air

- to line the movement of days

- unseen against the sky

- a flock waves upwards

Jennifer responds with her flute, the faintest zephyr of sound mixing with whorls of mist over the water. The drum signals a movement and we turn south, arms fully extended, palms up. Two squirrels raise a chorus.

- South

- rising an open hand

- flaming toward the heart

- to hold it fast and visible

- brushing the eye:

- eight dragonflies sown of the sun

Flute animated. High notes piercing the stillness. Drum. Arms at chest height, palms up.

- West

- echo of a stone

- circle’s sound worms marks in mud

- falling dark where

- inside the shadow

- a slow year’s thunder found

Flute strong, decrescendo. Strong, decrescendo. Drum. Arms at hip height, palms down. An osprey overhead:

- North

- a floating odour

- lifts the veil in a noiseless breath and is gone

- cupped waves and fish

- over the fretted sea

- flying

Skirl of wind from the flute. Biting. Sixteenths again from the drum.

We all turn to face the centre of the circle with arms crossed on our chests. I speak:

- dawn once more again

- comes as a birdsong psalm again

- through leaves that green

- with light’s cascade again

- wake wonderful

- marvel morning

We open our arms and offer each other morning greetings. Marisa gives us her Brazilian Portuguese and wide smile: Acorda esplendorosa, maravilhosa manhã.

We all laughingly try. Our tongues tripping on the foreign but wonderful syllables. Acorda esplendorosa… maravilhosa manhã. Hey, that’s it!

And did you hear the wolves last night? Long, long tones; not the yipping and yapping of coyotes.

Yeah, just after midnight, from the northeast. We might see their tracks when we head over to the gorge this afternoon.

I think I could hear Janice singing all the way from Wildcat this morning. I still can’t get over how sound travels up here.

Do you remember the time Wendy was practicing the aria and the loons started responding, gathering at this end of the lake?

Right, fourteen loons! Amazing. It was like they were singing back and forth to each other, the loons and the Princess. Wailing and calling. Look at all the spider webs. Hundreds of them spangled with dew.

You know the dew and the mist are supposed to be the tears of the Princess. Beautiful tears of sorrow.

After breakfast we’ll organize camp chores. There’ll be a bear safety session too. Usually I opt to set up tarps, collect firewood or dig latrines, but this year I think I’d like to work on the Wheel, which needs to be relocated. The path we usually take to the head of the lake, where the old Wheel was situated, is under water thanks to a new beaver dam, and our access through the swale will be impossible. Perhaps that open space where we did warm-up exercises last year will do. We can still look down the length of the lake from there and none of the tents will be visible either. Let’s check it out. And show Ted the details in the script. He can help sort out the four directions; always a good job for a new guy. Get him oriented to the ritual and the landscape.

The Wheel of Life

The concept of the wheel of life can be found in many cultures. Its four main directions stand for East, South,West, and North, as well as for Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter, and also for Infancy, Adolescence, Adulthood and Old Age. Thus the Wheel of Life is a circle uniting all things and illustrating the relationships between them. Through their daily exercises, stories and rituals, the clans have been made aware of many of these relationships. Each campsite will have its own Wheel of Life, independent of the Great Wheel where the ritual of the final day is enacted. When the clans gather on the final day to form a circle of eight equal parts, it is as if by extension all creatures, substances, sensations, and ideas on earth are included in the Great Wheel of Life.

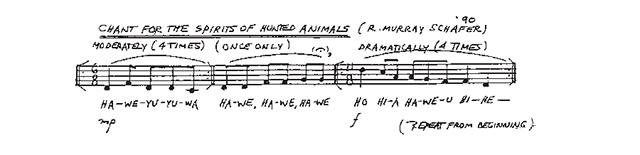

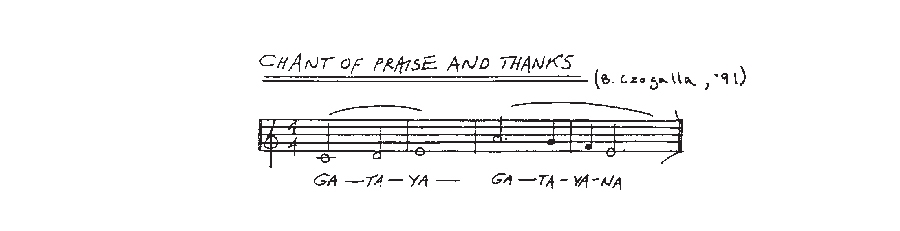

The Wheel is a pathway circumscribed with driftwood, stones and woven branches. Hand-fashioned totems mark the respective locations of the clans. Feathers, shells and bones found along the forest trails are often brought back to the Wheel to serve as reminders of our adventures away from our home site. Perhaps an exchange with another clan will result in a new sculptural piece. As the centre of the ritualized day, the Wheel is opened each morning and closed each evening with choral chant.

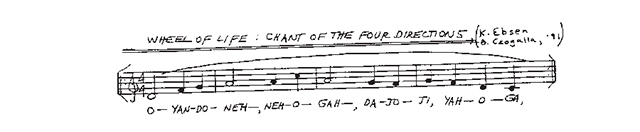

The words come from the Iroquois for the four winds. We sing them as a mantra, a meditative preparation. Before entering the Wheel, clan members touch the earth and speak the Lakota phrase Ho Mitakuye Oyasin, meaning “All my relations,” to remind us of the interconnectedness of all things. This reverence, so much a part of North American native spirituality, is what we also seek to foster. Even so, some of us have misgivings about appropriating language and symbol.

After much thought, I’ve come to embrace the inclusion of such elements as a tribute to native cultures rather than a raid on insights for the sake of art. Stealing native teachings is misappropriation; learning from the discernment is homage. Also, consider the pan-mythic context of Patria. Sweeping across Greek, Egyptian, Chinese and Scandinavian cultures, it borrows and celebrates images, characters, actions—melding and juxtaposing. How fitting, then, that the epilogue is informed by the aboriginal cultures of North America, the location where we strive to set the world aright.

Standing outside the proposed circle, we can feel the feathery needles of white pine brush against our faces. At the lake’s edge, the wind flips up a few water lilies, and the Ojibwa Star Maiden’s presence is felt.The new site for the Wheel seems ideal. Ho Mitakuye Oyasin.

Encounters

Ready to rehearse, the Bear clan heads out to their Encounter site today: the realm of Shalana. It’s a half hour hike over the ridge, along a network of beaver dams and through dense forest that opens to a wide sedge meadow edged with black spruce and tamarack; after that comes the spectacular gorge and tomb of Shalana. Once the leader of the Human clan, Shalana did not believe Humans were superior to the other animals, but his words were not heeded and Human arrogance, greed and destruction prevailed. Yet there are those among the various clans who seek to re-establish concord, and if they can successfully make the journey to where Shalana is entombed in stone, they might hear his oracular voice and learn what must be done to amend the upheaval caused by Humans.

As the Bear clan, our job is to present the ancient story to the clans and provide the much-needed voice to inspire change. Each clan prepares an Encounter for the others: it may be a theatrical piece providing a back-story to the upcoming events of Great Wheel Day, or a meditative or sensory preparation for the final ritual. Creating such an Encounter helps each clan coalesce around a common purpose.

As we walk the trail to the gorge, our heads are often down, checking our footing among roots, fallen branches and moss-covered rocks. Look, a clump of oyster mushrooms we can gather on our way back for supper. And there, stalks of Indian Pipe thrusting through the leaf litter. Of course, bear scat always gets our attention. The hike also affords time to memorize lines. Even though the script may be the same as last year, the person assuming the role might have changed—perhaps just today. And always there’s tension between the forces of ritual and innovation. Dancers we didn’t have before have to be incorporated into the story, but we only have today to rehearse because tomorrow afternoon the Beavers, Squirrels, Loons and Foxes will be here to see the show. Okay, right. It’s not a show, but you know what I mean. The performance… no, that’s not it exactly either. Yes, the word Encounter seems just right. Watch that stepping stone! It’s not stable! Mike got a soaker here last year crossing the stream—and a nasty, gashed knee.

When we emerge from the hardwood, through a thicket of young spruce and a tangle of alders, we stop to survey the panorama. The open meadow seems so peaceful as we gaze across the grassy expanse to the far wooded margin. A flicker makes its long, loud call. Sometimes a turkey vulture floats overhead, lifted by currents, nourished by death. Its characteristic wings help us to identify the bird, acknowledge its role. The scavenger is a testament to another drama that takes place daily in the forest. Life so fecund that only death sustains it. Where then do humans fit in the larger drama? How does recreating a story every year help to restore harmony? That’s a question for campfire tonight.

The gorge up ahead raises questions too. Questions of time and change. A great torrent of water roared through here once, glacial ice grinding against the Precambrian rock. Now the water’s just a trickle, here and there the occasional pool where fingerlings dart and scatter as we walk by. Looking up over a hundred feet, we scan the rock walls and observe the tenacious roots of trees, cedars and birch, clinging for life in the lichen-encrusted crevices. The air is cool at the bottom of the gorge, the light mottled, but it opens to the most magnificent blue sky and white cumulus. This now is a place of relative tranquility, where at one time great forces of energy churned and carved. We feel humbled and reverential, open to epiphany. A delicate cardinal flower blooms along the rocky edge of the stream; deep within the gorge, a ruby-throated hummingbird has found its way to the flamboyant, scarlet offering.

One Ruby-throated Moment

- if only

- for one

- ruby-throated moment

- your life could hove

- rapid

- radiant

- rare

- you would never let the quiver

- out of your bloodstream

- seek always the nectar

- you sensed was there

- if only for one

- ruby-throated moment

- your heart could beat

- a hundred thrilling times

- a hundred exclamations

- a hundred revelations

- a hundred prayers

- if only

- for one

- ruby-throated moment

- you could drink

- from the chalice

- of the sun

Life lived with intensity. Our own journey here brings us to the verge of flight, the threshold of illumination.

In this natural cathedral we will stage our Encounter, inviting the clans to take the difficult path through the gorge to hear Shalana’s disembodied voice speak from ancient stone. His urgent admonition to gather all the clans, to build The Great Wheel, and to perform the sacred ritual will be the call to action. We have become part of the myth-making, have entered into the story with conviction. And to project this mythic voice, we’ve got a fourteen-foot alphorn with sixteen-inch bell to wedge in place among the rocks and hollow log camouflage. Let’s get a move on.

Encounters unfold over the course of several days. The Squirrels, Tapio’s helpers, sensitize the other clans to the natural environment through soundwalks and listening adventures. The Loons evoke characters from other Patria works, juxtaposing them in strange contexts. Addressing past mistakes from a misplaced work ethic is just one theme of the humorous Beaver Encounter. And Fox, focussing on Shapeshifter, presents a volatile piece at the edge of chaos.

Silence and contemplation characterize the Turtle experience. Come to the edge of the cliff. Select a stone. Feel it with your fingers. Place it near your heart. Wordless instructions are given by simple gestures. Exchange your stone with the person on the right. Return it. Feel it with your fingers. Place it near your heart. Exchange your stone with the person on your left. Return it. Feel it with your fingers. Place it near your heart. Each of us now holds a stone that we have become attached to through these simple movements. We watch as the leader of the motions casts his stone into the water below. One by one we relinquish our stones, throw them out into the air. Loss, loss, loss.

Looking down, we see a woman in white. She begins to sing wistfully as she steps from a lower ledge into the water. Remarkably, she continues to sing as she swims, her gossamer dress billowing about her. Across the bay, we see a masked figure on the shore: the magnificent White Stag, wounded. The swimmer makes her way toward him, singing all the while. We watch as she nears the far shore, her voice gradually diminishing in the distance. Behind us, strange oscillating tones. We are enthralled by her yearning. The stag bolts.

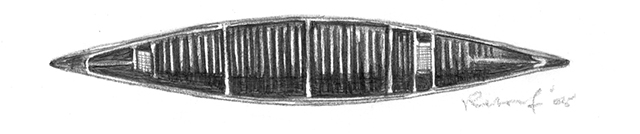

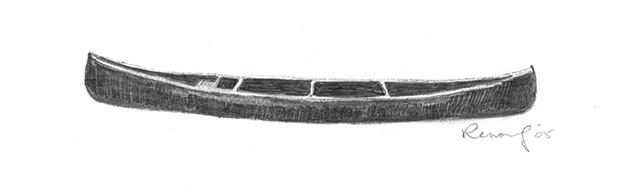

The Haetempka Encounter is a solo quest. Arriving at Crow Lake in our clans, we are told to separate and prepare for an individual journey. We must remove our boots; then, one by one, we are taken by a Crow guide down to the water’s edge and a waiting canoe. As instructed, I lie down in the bottom of the canoe, cradled by the cedar ribs. Fresh cedar branches, richly redolent, are laid on top of me. My entire body is covered, but I can see through the green filigree to the blue sky and billowing clouds, yet that is the limit of my vision. I am reminded of the perspective looking up from the bottom of Shalana’s gorge. The canoe, paddled by a Crow clan member in costume and mask, departs; the rhythmic sounds of the water lapping against the hull are deeply comforting. I have never been recumbent in a canoe before. It’s disorienting. I cannot see the shore and have no idea where we are headed, but I surrender, trusting the guide. After several minutes, a soprano voice fills the firmament above me. I cannot tell exactly where the aria is coming from, surely the shore, but where is that? The sensation is both distant, ethereal, and intimately near. Looking skyward through the cedar branches, the ribs of the canoe hard beneath me, rocked by the waves, listening to an angelic modulation of sound. My sensibilities are at a keen edge.

The canoe, slowing, gently rubs a rock. The soprano voice is gone. We stop. I can see the underneath of pine limbs arching above me. We have reached a new shore. The cedar branches are removed. I am told to take the trail that lies ahead. My Crow guide pushes off in the canoe, and I am alone, barefoot.

This is the trail, I hope, that will lead to the medicine woman, Haetempka, companion of Shalana. What will I discover along the way? And if I find her, what guidance can she offer me? She is a solitary old woman living in a hut. Will wisdom reside there? I take my first tender steps. Pine needles and sap. Sharp stone.

A night Encounter has real dangers, but it also offers a heightened sense of awareness. For Deer, we arrive at twilight by canoe. Bats flit over the water; a barred owl hoots its familiar refrain. Gathering as a flotilla of canoes in the bay, we quietly scull to keep our place on the calm water. Each canoe has a small lantern hung from a branch, placed in the bow. In this crepuscular time, we float among our many reflections on the water, awaiting dark. Gradually our forms disappear and only the bobbing lights remain. From the shore a cymbal sounds, now a bell. Across the bay a triangle rings. Quiet. The cymbal again out of the darkness. To the south, over the rising hillside that defines the bay, the full moon begins to rise above the trees. The triangle dings. The first faint notes of an accordion come to us across the water. Now the bell again. A paddle knocks a gunwale.To the north, faint wisps of light. No, it can’t be; it’s almost too much—as if on cue, the northern lights begin. An acoustic bass joins the accordion in a soulful duet. The moon breaks free of the trees and continues to rise. Hints of colour come into the aurora borealis. Frenzy now in the bass. Two canoes touch and part. Only the accordion now. A punctuation mark from the cymbal. Then out of the darkness, rimmed by the light of the full moon and the mercurial choreography in the northern sky, comes an overwhelming sound. A female voice. Anguished. We are rapt.

The mezzo aria fills the entire bay, surrounding our lighted, drifting canoes. No one could summon the display in the sky, but the lights have come, as have we. The synchronicity is utterly mystical. Eventually the human voice fades, the final triangle sounds, the last trace of dancing light only a memory. We notice our hands again, cold on the still paddles. We pull the blades strongly, silently, through the dark water and head back to our site. Lanterns swinging on our driftwood bowsprits.

Children

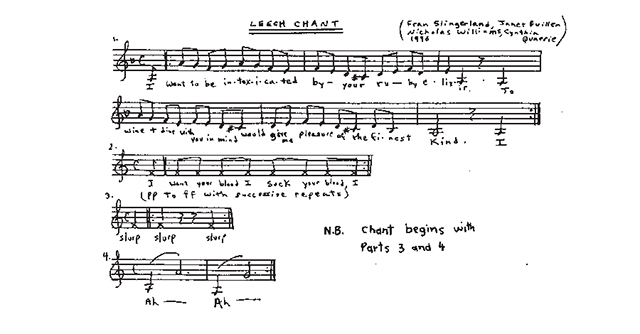

I once heard Murray say that the children were the barometers by which to measure the imaginative success of the Wolf Project. As long as they remained immersed in the mythic story, singing the chants and telling the tales, there was real vitality to what we were creating. But if the kids started singing pop songs around the fire or discussing TV shows, that meant there was no sustaining lifeblood to the mythic drama. Did I say lifeblood? Okay, how about the leech chant!

The kids love making the slurping sounds as grotesque as possible. What’s an elixir, they ask? Something that enables you to live a long time, I say. And laughing with the children, I begin to think I’m drinking it in all around me. Having had a taste of the agreeably repulsive, the kids clamour for more safe danger and the delight that comes from the tease of language that remains just outside the “gottcha” zone. Let’s have “The Bear’s Belly” they call out.

The Bear’s Belly

- when a bear’s belly’s full of berries

- not one more berry can fill a bear’s belly

- because the bear’s belly’s full

- so what does the bear do

- with the one more berry that can’t fill

- the bear’s belly

- well he puts that berry

- in his bear’s belly button

- because that’s the one place that’s not full

- so if you see a bear

- with a berry in the button of his belly

- you’ll know that bear’s belly’s full

- but should you try to take that berry

- from the bear’s belly button

- well then the bear’s belly will soon be full of you

Dissent

Yes, conversation around the campfire occasionally turns to complaint. Not usually about the weather and certainly not about the food. If someone puts on a wet log that smokes and hisses, good-natured bantering might ensue, but personal sniping is minimal and not part of campfire time. Yet one criticism does seem to emerge every so often as the flames die down and the atmosphere turns pensive.

The whole thing is a bit patriarchal, don’t you think?

Yeah, the Princess is too subservient. She doesn’t even make it into the title. And all Wolf can do is rage.

They’re really just cardboard characters, someone says, poking the fire and stirring up a profusion of sparks, fiery seeds that embolden me to speak.

You’re Wrong about Wolf

- you’re wrong about wolf

- a little too one-sided

- quick with your own teeth

- those jaws can tear apart a deer

- or be as gentle as a swinging cradle

- and carry a pup out of danger

- quick with your eye to condemn

- do you think those eyes have never known grief

- staring at the stiffened carcass of a mate

- in a winter gnawing with hunger

- quick with your nose in the air

- wolf can smell hypocrisy

- masking your own wolf scent

- with the feces of righteousness

- you’re wrong about wolf

- a little too one-sided

- and glistening fangs

- in the stealthy paws

- there’s beauty

- there’s beauty

- in the howl

-

you’re wrong about the princess

- a little too one-sided

- the princess casts a shadow

- when she walks

- her footsteps crush the snails and the spiders

- a crown of stars can tarnish

- behind a veil of swirling cloud

- you’re wrong about the princess

- a little too one-sided

- if you examine her smile

- you’ll find canines

- next to her incisors

Great Wheel Day

At last: Great Wheel Day. The clans have arrived from their various sites and gathered at Wildcat Lake. Eight clans of eight. Everything has been building to this day of drumming and dancing, this day of vivid living, exaltation.

After an energizing vocal rehearsal led by David, we have a half-hour for a quick swim before our “call.” Is it theatre, ritual, or a way of life? David has infused our choral warm-up with a sense of enchantment. After all, our purpose is thaumaturgic: to evoke Wolf and the Princess, to bring them together at last, to change the world.

Costumed and ready, we line the sloping trail down to a pickerelweed pond. In theatrical terms, we are waiting in the wings. But we can hear a tumbling cataract to our left and noisy jays high in the canopy above. Here, “behind the scenes” is the scene. For fifteen years, I’ve organized my life around this moment, being here on this day, in this forest, with these people, to live inside the “character” I play. In ritual terms, we are not now merely going over our lines—we need to get the lines and action right to succeed at bringing about the mystical union. If we err, no apotheosis.

Bears are an earnest group for the most part. Beside us are the irreverent Beavers in their orange garb, characteristically busy making last minute adjustments to their bottle cap rattles, stick necklaces and flapping tails. For all its import, the day is far from humourless, and the Beavers are good at counterpoint. The Crows, some in iridescent headgear, others in shimmering capes, are just up the hill from us, practicing a movement with their capes that will conceal Haetempka’s later transformation in the inner circle. The Loons go past, Maya and Sean stretching out their wings. They were young children when they first came to Great Wheel Day. Maya an infant, in fact. Now they have grown into agile dancers, and fine actors and singers. And my sons, Caley and Devin, have stood on this path with me, too, in past years. Yes, a way of life.

It’s Tapio! His alphorn summons us, and we begin the elegantly incongruous procession to Moose Rock, our entry point to the meadow and The Great Wheel beyond. The hierophany has begun.

After presenting our clan totems to Tapio, we are ready to enter The Great Wheel in the heart of the meadow, a sweeping expanse of alder, leatherleaf, juniper and sedge. Acres and acres of open space with occasional thrusting rampikes, skeletal, dead tree trunks towering above the low growing bushes. It’s a striking contrast to the dense forest. The vastness and the overarching panoply of sky create an architecture of amazement. The Great Wheel spans a hundred feet in diameter, a circular path demarcated by twists of old tree limbs and upturned roots, decorated with clan banners and forest found art: bones, feathers, antlers. At its centre, stands the tallest of the rampikes: a giant pine, now truncated, bleached and hollowed—the point of convergence for our theatrical incantation.

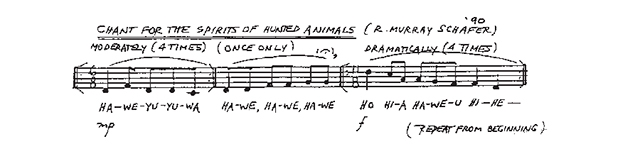

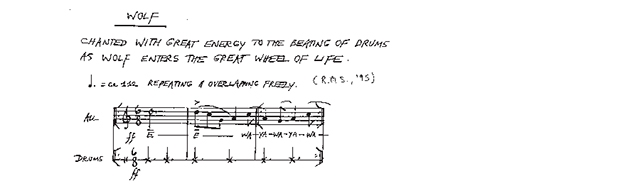

Singing OYan Do Neh in unison, the clans process ceremoniously to their locations around the Wheel: Deer in the East, Turtle in the South, Bear in the West, Loon in the North. We are all here; we have travelled many miles; we are anxious to begin. Wordshaker, rattle in hand, calls us to the Wolf Chant. We move to the inner circle, arms around the shoulders of our fellows, feet ready to find the ancient dance.

The chant ends in a protracted howl. Sixty-four wild vocalizations. I look across at the circle of open mouths, piercing eyes.

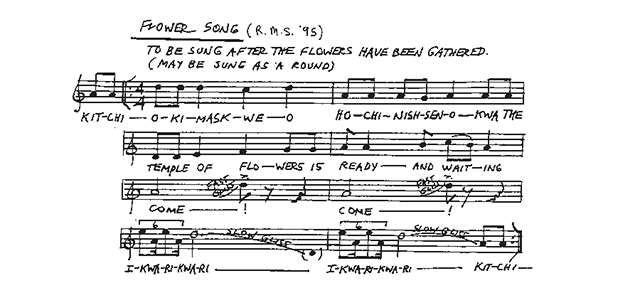

Now to the sacred circle comes Haetempka. She reminds us of our other nature, the need to call forth tenderness, beauty and joy. She entreats us to construct a flower temple, a bower, and to sing for the Princess to elicit her presence.

To gather the flowers we must leave the Wheel and find that delicate beauty among the tangled vegetation. With the others, I move sun-wise and exit the circle, moving through the arched saplings that form the bower, soon to be decorated with goldenrod, daisies and asters. I pause to bend, to touch the earth, to say the ritual words as I leave the Wheel, all according to the prescribed custom. The next time I enter this space, I will be contemptuous of such ceremonial conventions. I will not move from east to west; I will not bend; I will not mouth conforming maxims. I will leap into the circle, drumming wildly, spitting words of rage. The next time I enter this space I will be Wolf.

The bower music begins as I take a snaking trail back in the direction of Moose Rock. I leave the group behind, crouching low in the alders to avoid notice. Lift my mask so I can see, slip out of my bear robe, break into a trot. I am shaking off Wordshaker. Just outside the circle medieval music and dancing is underway. Recorder and mandolin. Decorous movement and an atmosphere of spontaneous gaiety. It seems a world away. Ahead another mask awaits, hidden in a tree stump. A wolf headdress, two striking yellow eyes and a row of sharp teeth. I snarl.

Water, water! Thank goodness I remembered to leave a bottle here. I gulp it down. Find my drum and beater, a unique drumstick fashioned from a Brazilian tribal arrow and decorated with feathers. A nod to A Floresta Encantada. From a different direction, someone else arrives at an adjacent stump. It’s Alec; he starts getting into his gear. I share my water with him. He helps me adjust my headdress strap, while I hold his rifle. Soon he will be the Hunter stalking me from tree stump to tree stump through the meadow. Now we wait together for the cue. Eventually I will circle back on him, mirror his movements. When I kill him, I will feel absolute triumph. MAHIKUN!

With the death of Hunter comes the emergence of the White Stag. Shapeshifter incites the transformation, dancing with the body of Hunter into a nearby stream. As Hunter sinks beneath the water, the White Stag rises out of the reeds, summoned by the evocative dancing of Shapeshifter. Wolf, gloating after his kill, has run into the forest unaware of how this transformation will lead him into the ritual circle.

I leap across a small crevice, swing up and over deadfall, scramble low along a lichen-encrusted outcrop and find my hiding place. More water. The script too, stained and folded, for assurance. I can smell my sweat. God, it’s good. Breath in heaves. I can hear the clarinet for Shapeshifter’s dance, although I can see no action. Fifteen minutes alone before my next cue, good. And blueberries within reach. When the call for Wolf comes, I will explode from here, legs thrusting forward, lungs at the full, drum held high. When the call for Wolf comes, I will live at the pitch that is near madness.

Returning to the Wheel, the clans tether the White Stag to the rampike at the centre, a living sacrifice offered to Wolf for the taking. The elements of the ritual are converging. The bower, a sanctuary for Ariadne, is decorated, awaiting her imminent arrival. Will she appear? The answer comes from a distance, a joyful thread of sound. No one breathes. Another strand, frayed by suffering. It must be her. There in the east, she approaches, radiant, but without her crown. She sings of her past lives, her descent from the heavens, her wandering on this earth. And as she comes closer, she acknowledges the sacred ritual that has brought her to the edge of the circle:

- NOW YOU HAVE BUILT THIS TEMPLE OF

- FLOWERS TO WELCOME ME INTO THE

- GREAT WHEEL OF LIFE.

- THE RIVERS AND LAKES,

- THE FLOWERS AND FERNS,

- THE ROCKS AND HILLS,

- ARE DANCING WITH JOY.

- O ANIMALS

- EARTH FRIENDS

- I COME TO YOU

- I SING TO YOU

- I HAVE COME TO GREET THE WILD ONE!

- CALL HIM . . . CALL HIM . . .

The clans are fervent. Howling in response, they move into the centre of the Wheel to exclaim the Wolf Chant and perform the dance for the second time. The energy is fearsome. Teeth bared, heads thrown back. To call Wolf to the circle demands Wolf in the blood. We all have it; few allow it out. Yet here in the meadow, round the storm-blasted rampike and panicked Stag, wildness spirals in a sonic vortex.

Concluding with a tumultuous howl, the chant ends raggedly. A barbed hook in the open jaws of Wolf. The ritualized clamour yanks him from his hiding place; he bursts forth in a frenzy of drumming and chanting. Wildness begets wildness. Havoc comes, foaming at the mouth.

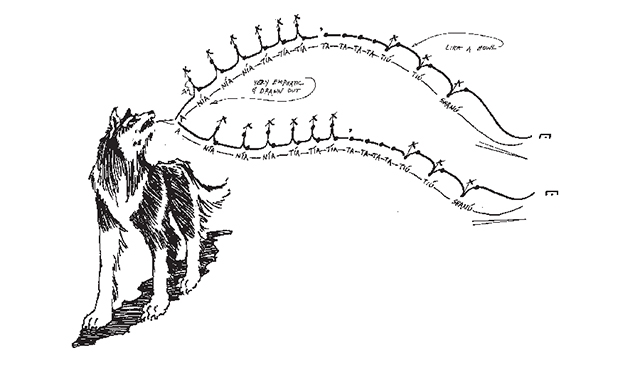

- A-NÍA-NÍA-NÍA-TÍA-TÍA-TÍA-TA-TA-TA-TA-TIÚ-TIÚ- SHANÚ

- SHANÚ TUMÉ SHANÚ TUMÉ SHANÚ TUMÉ

- YUS YUS YUS, MA-HÍ-KUN

- SHANÚ TUMÉ SHANÚ TUMÉ SHANÚ TUMÉ

- YUS YUS YUS, MA-HÍ-KUN

- TUMÉ-ONI TUMÉ-ONI THÁI-ONI WAYÁ WAYÁ

- ANI-WAYÁ WAYÁ WAYÁ ANI-WAYÁ WAYÁ

- O-THAI-ÓNI O-THAI-ÓNI O-THAI-ÓNI ANI-YAYÚ

- YUS, YUS, YUS, YUS, YUS, YUS

- NÍPA-WUMYUS, YUS, NÍPA-WUM

- YUS,YUS, NÍPA-WUM YUS

- BOK-TÚSIM BOK-TÚSIM BOK-TÚSIM

- A-NÍA-NÍA-NÍA-TÍA-TÍA-TÍA-TA-TA-TA-TA-TIÚ-TIÚ- SHANÚ

- ANÍ-WAYÁ WAYÁ WAYÁ ANÍ-WAYÁ WAYÁ

- O-THAI-ÓNI ANI-WA YÚS, YÚS, YÚS, YÚS

- NÍPA-WUM YÚS, YÚS

- NÍPA-WUM YÚS

- PA-WUM YÚS, YÚS

- PA-WUM YUS, YUS

- PA-WUM YÚS, YÚS, YÚS.

Wolf arrives at the Great Wheel. The clans, once so fierce in summoning, cower at his approach. What have they unloosed?

WOLF: IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT I ROAM, READY TO TEAR UP THE WORLD I ROAM. CALL ME WOLF!

ALL: WOLF!

WOLF: IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT I ROAM, SHIVERS RUNNING UP MY SPINE I ROAM. CALL ME WOLF!

ALL: WOLF!

WOLF: IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT I ROAM, EYES IN THE BACK OF MY HEAD I ROAM. CALL ME WOLF!

ALL: WOLF!

Disdainful, Wolf leaps into the wheel with no regard for the rules of entry. He hurls himself across the open expanse like an avalanche, erupts from behind a stump like a volcano—these after all are the alternative lives he has been leading—and comes face to face with Bear, threatening to devour the sweet brains of his enemy. Bear stands his ground, regards Wolf eye to eye. For a moment, stillness. Then rage returns, but with a difference, as though Wolf has punctured his own tongue with his sharp teeth. The mood shifts, becomes almost melancholy. He speaks of his life as a fugitive, wandering to find the Princess. It’s only a slight deviation, not a weakness. Surely. He gathers himself again into apocalyptic thunder:

- WITH MOVEMENT SWIFT I RISE

- LIKE THE BEAT OF CROW’S WINGS

- WA-YA WA-YA WA-YA!

- FROM THE DARK OF NIGHT I TURN

- TO GAZE AT THE LIGHTENING SKY.

- WA-YA WA-YA WA-YA!

- DRAWN BY THE SCENT OF THE STAG

- I COME TO THE CIRCLE OF LIFE

- A-JA A-JA

- WA-YA WA-YA WA-YA!

- TODAY IS THE END OF THE WORLD-

- OR ELSE THE BEGINNING!

- SHANU WA KIA

- SHANU WA KIA

- A-JA A-JA HA-JIA HA-JIA

- WA-YA WA-YA WA-YA

This is the moment of bloodlust that the clans have orchestrated. The White Stag shifts nervously, sensing his own death. The clans break into dithyrambic chanting, stomping the ground with their feet, urging on Wolf to the kill. The whole scene is primeval. Savage.

Wolf lunges at White Stag. A macabre dance of rapacity and fear. Wolf throws back his head, ready to sink his fangs into the Stag’s neck. A convulsion surges through the clans, but with it a new element comes cutting through the vocal clamour: the obbligato voice of Ariadne.

Jolted from his purpose,Wolf staggers, incredulous.With one mighty blow to his drum he calls for silence. MA-HI-KUN! All movement ceases, save the twitching Stag, the aspens fluttering at the edge of the meadow, dragonflies, clouds. Stammering, Wolf tries to addresses the change coursing through him like a tidal bore against his own current of rage.

- WHOSE VOICE KEENS THROUGH MY LUST?

- SORROW SINGS INTO MY BLOOD.

- MY EARS BETRAY ME.

- WA-YA,WA-YA,WA-YA

- MY JAWS TREMBLE, SLACKEN.

- WHERE IS THE SNAP OF BONE?

- WA-YA,WA-YA,WA-YA

- I WANT TO LICK THE WOUNDS MY TEETH HAVE RIPPED.

- I WANT TO LISTEN TO THEVOICE THAT SINGS IN MY BLOOD.

The drum falls from my hands; my grip on the beater loosens. It drops to the earth. My body trembles. Ariadne continues to sing; and the clans, swept away by the shift in energy, take up her lament. The choral transformation is astonishing, breaks over me like a wave. I surface, succumb, and surface again. I try to find my anger: WA-YA,WA-YA . . . but it’s feeble. One pounce and I’d finish her. One swipe at that voice… I can muster only snarls, panting. YUS, YUS. PA-WUM, YUS, YUS. The Stag has found his feet again; I stroke his bleeding flank. The music guides me, soothes me. Ariadne bends to me. WA-YA,WA-YA. She reaches out her hand to me. Where is my war drum? She sings to me. Another wave and I yield. The Stag is spared. I reach out my hand to her… Wolf reaches… the clans… we all reach. The Princess sings:

- O MOON

- LOVER

- LIGHT OF MY NIGHT

- I COME TO YOU

- I SING FOR YOU

- I REJOICE FOR YOU

- WITH YOU… FOR YOU… WITH YOU… FOR YOU…

- TODAY IS THE DAY

- IN THE PRESENCE OF ALL THE ANIMALS

- YOU HAVE SHOWN COMPASSION.

My hand and hers enfold. Wolf and the Princess are one.

Jubilation! The ceremony has succeeded. Sun Disc sings the promise of apotheosis, the Princess to the stars, Wolf to the moon. There is dancing and more music. My dark journey is done. I have loped along harrowing trails, assumed a savage visage, touched extremities I didn’t know I possessed. Acting? Or passage into an alternate consciousness? I can’t think about that now. I have to get back from the pitch, the dizzying height. I have to breathe deeply, feel the hand in my hand as a human hand. Feel the reassurance, the grounding. I have to let Wolf go… let Wolf go…

The script draws us out of the meadow, up the ridge again to Wildcat Lake and the vista beyond, and calms us all with a change of tone. Quiet, reflective time now. The clans attend as Wolf and the Princess prepare for their departure in a cedar strip canoe, gunwales festooned with pine boughs. Their journey down the lake, paddling out of sight, is the first stage of their mystical ascension. When we see them next, they will be in the heavens. The Departure Music echoes all around us. The trumpet leads, high and arresting. Now a clarinet, a flute, a voice. Harmony is restored to the world.

As the music fades, only the forest sounds remain. The clans linger for a long time. Bound in the spell, no one wants to move. A gentle wind on the water. Sun. The scintillating lake, an illuminated scroll. Eyes meet in silent acknowledgement.

A kingfisher chatters along the near shore. Gradually, the masks come off. Flamboyant capes are tucked away. Headdresses returned to costume bags. The necklaces, strung with cones, slipped into pouches alongside crow feathers found on the trail. A grouse wing—something can be done with that for next year.

Eventually the kitchen crew howls for our final, festive dinner together, and we make our way along the ridge trail to the colourful network of overlapping tarps where we gather in the slanting, golden light of evening. It’s a congratulatory time: kudos to the cooks, hats off to the singers, a salute to the director, and a toast to the man who envisioned it all, and engendered in us the will, zeal and tenacity to create an eight-day life-changing pageant in the vast surround of the boreal forest.

Confluence

- For R. Murray Schafer

- rivers flow into rivers

- reflection scatters into spindrift

- wind wails into psalm

- so music flows

- into the bloodstream

- dance into the bones

- words breathe

- a brush stroke quivers a pulse

- stars jewel a crown

- a hunter antlers a stag

- an old woman withers into a girl

- a carcass births a young man

- and wolf rhythms the moon

- rivers flow into rivers

- I am a tributary of you

- you are a branch of me

- our waters swirl into clouds

- we river

- we rain

After dinner the mood changes. It’s a different kind of excitement. Fun time. That is, poking fun time. Parody and pastiche. Each clan has the limelight at the fire to present their version of, well, Wolf Moons the Princess or Three-Horned Enemy Gets the Girl. For the first time in a week, we hear the strains of pop and rock songs but with Schaferian lyrics and aerial riffs played on beaver tail paddles.

- I can’t get no transformation

- I can’t get no transformation

There is mock aubade: a morning awakening to the music of zippers zipping, noses blowing, Velcro rips—in truth, part of the real soundscape of the morning encampment. Now comes a Nalgene bottle xylophone rendition of O-Yan-Doh-Neh, and then a chorus line of high kicking Loons. The Bears are up next, adopting the point of view of Wolf, the disparaging loner, mimicking his derisive voice. We do a dance of sorts, a little burlesque, and scoff at the ridiculous notion of changing the world thorough art and anthropomorphized animals.

Nothing Rhymes With Wolf

- Round and round in the wheel they go

- Bear and Turtle

- Fox and Crow.

- Through the forest in petty fear

- Loon and Beaver

- Squirrel and Deer.

- But nothing—arrrr, arrrr—

- Nothing rhymes with Wolf!

- A hunter turns into a stag?

- A shining soul in a bag?

- Desperate ravings from a feeble hag?

- Forget the chanting;

- It’s all ranting.

- But nothing—arrrr, arrrr—

- Nothing rhymes with Wolf…

As the clans rotate through their send-ups, the laughter leaps like a freshly stoked fire. Soon it’s a bonfire of chortles, hoots, and roars. And rising above everything with gusto is Murray’s unrestrained merriment. He’s “the man in the purple pants,” so-named for his comically coloured rain gear, or “Murky Schemer,” as someone’s spell checker once dubbed him. He’s at the centre of our jokes now, just as he is at the centre of our incredibly rich creative community.

The mirth subsides; we put our arms around the shoulders of our companions. Gathered around the fire, slightly swaying, we slowly fall into the traditional Tyrolean air. We think back on all the week’s events, all the years we have gathered like this, all the different places we have journeyed from, and all the different places we will return tomorrow.

Out on the lake, the Foxes silently canoe in the darkness. Over the past several days, they have built a floating structure: The Firebird. Now, with a kerosene torch they light eight suspended braziers, representing the eight stars of the Princess’ diadem: the Corona Borealis. Fire and water. Flame and reflection. It hangs in the night sky above us, and it dances now, too, on the lake. As above, so below.

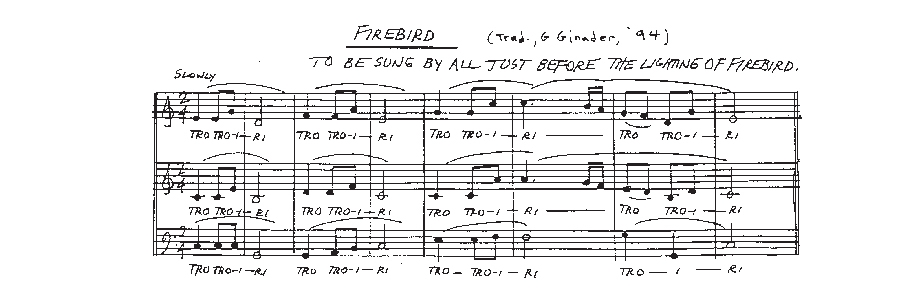

I have slipped away from the choral assembly atop the ridge and have met Wendy, the Princess, at the canoe launch. Wordlessly, we set out into the black lake, our paddles quiet, cutting silently through the water. As we approach the Firebird, the singing of “Tro-Tro-i-ri” gradually diminishes and dies out. Only the gentle rippling from the bow as we follow a path of moonlight out into the centre of the bay. Then amazement happens.

The Princess sings. It’s her final aria, the same as the beginning to Princess of the Stars, twelve pieces and many lives and worlds ago. It contains all the anguish of distraught love, winds its way through rejection and confusion, follows, for a time, a path of loneliness, reaches out to rage, transmits compassion, changes lives, and propels us all to exaltation.The aria continues as we paddle down the lake. The Princess turns her voice to one shore, now the other. Sound plays around us, echoes off the rocks, the hardwood shore.We come to the narrows, her voice funnels into the next bay, and returns. Stars are a manuscript of wonder. Distant loons punctuate our affirmation. The aria approaches its conclusion, a mere filament of sound–wait, perhaps it’s there still. Wolf, quiet until now, howls, a high, protracted ululation. Wolf and the Princess rise into the heavens. The Princess regains her crown, and Wolf inherits the moon.

Farewell Morning

The last aubade; the Wheel disassembled. One final sweep of the campsite. Everything packed out; nothing left behind. Even the wake of our canoes disappears on the wind rippled water. Heading for home, family, familiar lives. There’ll be stories to share upon our return,“circles of remembering.” We form a colourful flotilla, as our paddling falls into a smooth rhythm. Plunge and pull; plunge and pull. Little currents along the blade edges swirl into question marks. Has the world changed? Have we changed? What can art do?

The Searching Sings

- no birdsong verb ever can be found

- no cataract chant

- no wind wail

- no syllables as sibilant

- as reed whisper

- no tumble of words into waves

- what voice can rain

- how can lungs thunder

- mouths crack the trunk of a tree

- how can lips make runnels roar into rapids

- who knows how to hum summer

- like the cicada

- who knows how to tongue the notes of sleet

- yet the howl of a wolf

- will answer the howl of a man

- loons on a lake

- will cry when called

- and the mountain return

- the shout of its name

- no birdsong verb ever can be found

- but in the searching

- sings a resonant sound

- and song is telling

- what can’t be told

- song is awe made bold

- song is blood flow

- song is bone

- song is the silence of stone

- song is leap

- between man and bird

- song is spirit heard

Read more