Ken Victor’s Writing Space

By Ken Victor

My writing space is messy. It doubles as a home office, so work and writing are hopelessly intertwined. My ancestors watch all of this without commenting. Photographs of my parents, grandparents and great grandparents at different stages of their lives decorate the walls. A few quotes and poems taped to the wall talk to me: Wendell Berry’s poem How To Be A Poet, Martha Graham’s magnificent insistence that the artist must let their unique self flow unimpeded into their work, and Robinson Jeffers’ poem The Beauty of Things.

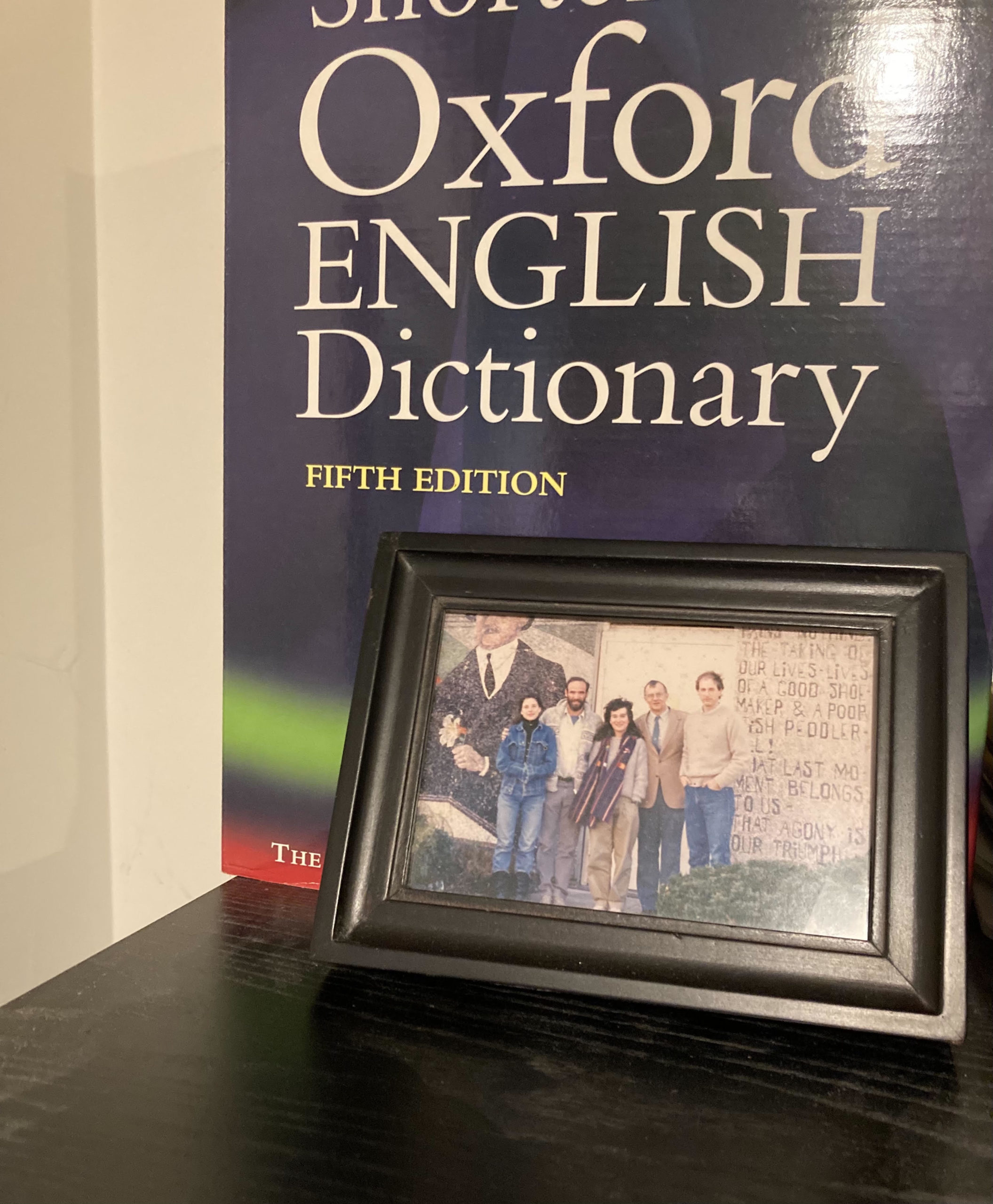

What is most precious to me though is off in a corner. If you were to come into the room you likely wouldn’t notice it. It’s a somewhat grainy photograph taken in the Spring of 1985 leaning—appropriately enough I suppose—against an empty box meant to house the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. The five people are huddled close together, they’re wearing sweaters and jackets, hands in pockets. It is the only photo I have from the small poetry cohort that spent two years together studying at Syracuse. Jane, Lucia, Chris, myself and our mentor in that spring’s workshop, Philip Booth.

Philip was known as a “Maine poet”, respected for writing beautifully crafted, meditative, lean lyrics of place. He was mentored by Robert Frost and could tell us stories of conversations he’d had with E.E. Cummings. Poetry is surely a place of ancestors, even more so than any wall of photographs, and Philip seemed like a direct channel back to ancestors whose work we knew. He organized the photo shoot that spring day, bringing his camera to the final class. We knew, without knowing why at the time, that Philip especially enjoyed our workshop together and wanted the picture. None of us could have known there would be no other record of that small cohort of hungry wannabees who had been called to the art.

Years later, in a conversation with Chris, I could surmise why Philip may have wanted the photograph. Chris would go on to eventually become the Director of Syracuse’s creative writing program which meant he would experience cohort after cohort of young writers. Few cohorts, it seems, bond; aspiring poets arrive and what comes next is anybody’s guess. The four of us, however, bonded like close brothers and sisters, appreciating one another’s writing, breaking bread together, supporting each other to thrive and, most important, internalizing each other’s voices of loving critique. Philip wanted, apparently, to document this rare occurrence.

“The four of us, however, bonded like close brothers and sisters, appreciating one another’s writing, breaking bread together, supporting each other to thrive and, most important, internalizing each other’s voices of loving critique.”

Time will clean the carcass bones, as one of Lucia’s poems says. She would go on to receive a MacArthur genius award, be in a wheel-chair by her 40’s from multiple sclerosis, passing away in 2016 after having an esteemed career in poetry. Jane would be a finalist for the International Griffin Poetry Prize in 2017. We planned to rendezvous in Toronto for the occasion, but Jane would be unable to attend as she received a diagnosis of uterine cancer a month earlier that would take her life a year later. Chris is still at Syracuse and stepping back from some of the demands of teaching.

I would leave Syracuse to move to Canada for work, poetry drifting to the periphery of my life. When I finally had a book come out in 2019, I felt like I’d completed an unnamed promise to that loving quartet from years ago. And what matters most to me in the book isn’t any poem, but the page at the back where I thank them in writing. That small photograph in my messy office is—in its own way I realize now—a picture of ancestors. We may grow into who we are but we are surely descended not only from our younger selves, but from those who accompanied us through passages best navigated in their presence. The poet I have finally become is their last gift to me.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Read more