The Plague Came with No Directions

A Blue Dot of Best Intentions

A few years ago, I got stuck in a field of thorns in the pyrenees. I was there to do research for a novel on the years of exile endured by German literary philosopher Walter Benjamin. He and I were outrunning catastrophe and found ourselves on that same twisted path of wild rosemary and sage. We had our reasons. The Jewish Benjamin had the Gestapo hot on his trail. I had demons. The trail had been carved over centuries by smugglers. Contraband was secreted up from the port of Lisbon and deeper into Europe; the persecuted and criminal were secreted to safety; Spanish rebels and fascists smuggled fighters and weapons not five years before Benjamin found himself there. I knew this history. It never occurred to me that I might die exploring it. It never occurred to me that I would find a metaphor for what it’s been like to live with HIV and trauma.

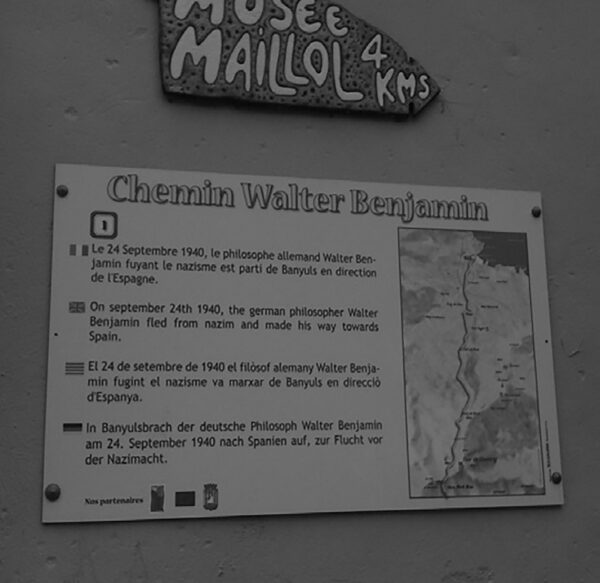

The day before, I’d taken the TGV from Paris. I spent the night in Perpignan, Salvador Dali’s heaven near the French/Spanish border. In the morning, I caught the train to the little beach town of Banyuls-sur-Mer. When I arrived, the shopkeepers were rolling up awnings and rolling out carts full of fresh fruit on the banks of the Mediterranean. A Saturday of tourists, shoppers, and sun-seekers, would follow. In French, the tourist bureau pointed me to where to pick up Benjamin’s trail.

That morning in 1940, he and a small band of refugees hid themselves behind a low-slung sheep wall. On the other side, a crowd of day workers waited to be hired. Knowing that Benjamin and others like him were in the vicinity, the Gestapo kept a close eye on these hiring sites. Benjamin, improbably dressed as a laborer, aimed to sneak over the Pyrenees to Spain. From Spain, he would head to Lisbon. There, he would board a steamer to New York. For the Nazis, Benjamin would be a prize catch. In the predawn hours, he and company snuck through the bleating sheep and onto the steep trail. Benjamin, lugging his valise, moved more slowly than the rest.

I had come to hike that trail, too. To smell the smells, kick the dust, and feel the ache of the climb. Unlike Benjamin, I was in good shape. He had a heart condition; I run two hours at a stretch. He had a valise that he wouldn’t let anyone else touch; I had a sandwich and some water. Benjamin had Lisa Fittko to guide him; me, the iPhone GPS. On the phone, the trail was a purple line. My location was a blue dot. As long as I kept the blue dot on the purple line, I’d get where I was going. As long as Benjamin made stops to catch his breath, he’d make the Spanish border. For what we intended, we were good to go.

Today, Benjamin is a cottage industry in places like Banyuls-sur-Mer. So, on a canary yellow wall a couple of doors down from the tourist bureau, a handmade tile plaque marked Benjamin’s starting point. That tile and the blue dot led me through the residential neighborhoods and, after crossing a rickety bridge, to that sheep wall. Incredible. I ran my fingers across its fieldstones and the blobs of cracked cement plugging up its holes. I imagined that Benjamin would have hidden on the other side so I leaned over to peek. And leaned farther. And then a bit more. The ground was much lower on that side. A good hiding place. Like so much of the landscape I was about to enter, it tricks the eye.

Carrying on, the blue dot wobbled off of the purple line. After meeting a German who cautioned against smartphone maps, I landed back at the sheep wall. Right where I started. The blue dot found the purple line. Hours later, well into a steady climb, a fork opened in the road. In the center, a sign: “Walter Benjamin Trail.” An arrow pointed straight up or straight down. That did not seem promising. Behind me, and far below, lay Banyuls-sur-Mer. To the right, steep cliffs and scrub. To the left, a spill of hills just like Malibu’s. Spain was more to the left than to the right, so I headed left. The blue dot hugged the purple line. A chalk marked confirmed it.

I was on my way. Then, the trail ended.

The phone map blue line indicated that it continued all the way to Portbou, the Spanish border town where I was headed and Benjamin died. I sniffed out what might be the path and walked a bit. The blue dot bounced off, but then returned to the purple line. I carried on. The French sun burned hot. I stripped off the bottoms of my hiking trousers, checked the phone and — shit. The blue dot had bounced beyond the ridge looming up to my right. In all my research on hiking the trail, it had never been mentioned that one might get lost; that one could get lost; that the signage was unclear. I backtracked, went farther on and backtracked again, scoping out the nearest thing to a path. The blue dot skit off, but then returned to the path. I was back on track.

Soon, though, the blue dot jumped to a path high above that ridge. Above the neat rows of somebody’s vineyard, I started climbing. The ground grew crumblier with each step. I hopped the first of several two- or three-foot-high bricked walls. And then, another. A zig-zagging path to the right cut through the vines and eased the way up. Voluptuous green leaves coated scarlet-tinged spears twisting their way along tidy beige rows. The vines staked, raked, and maintained. Not a person in sight, though. The higher I climbed, the more the wind kicked up.

A little trespass never hurt anybody, or so it seemed. I’m a trespasser from way back. No one could grow up in my family of origin and not know the value of disobeying rules. On the one hand, trespassing bred the feeling of being an imposter in my own skin; on the other it likely saved my life. I know all about trespassing.

Lost at Sea, Right from the Start

In my family, the ship was always sinking. It was clear from the get-go. There’s a snapshot of me at about three, backed up against the side of the house, baseball cap cock-eyed, forearms cocked to the camera, ready for attack.

I knew the drill even then: duck my parents’ knee-jerk need to suspect, accuse, and shame: each other, the world, their kids. They fucked hard but landed punches, and furniture, harder. From the front porch, we would peek through a slit in the living room curtain: Mom shoved the eight-foot sofa into dad. He didn’t respect her, she screamed. The sofa crashed into him but then he’d return the favor, pinning her to the wall until she screamed she couldn’t breathe. I got you, babe. They gave as good as they got.

We kids balanced on the tips of our toes. Ready to bolt, duck, or escape. An attack could come anytime or anywhere. There were always incoming missiles. Once I made the mistake of shoveling an elderly neighbour’s sidewalk without asking the woman first. It never occurred to me to ask for permission — or money. I just did it. Kindly, she gave me a dollar. But, Mom and Dad went ballistic. They accused me of conning her. Dad marched me back to apologize and return her dollar. She refused, he refused. From then on, I’d keep my big mouth shut and any genuine impulses under wraps. I learned to be suspicious of myself. But that might’ve been misguided.

Mom’s attacks came out of nowhere. She ran on coffee fumes and an hour of sleep. Charging into our bedrooms in the middle of the night, she’d drag us out of bed, forcing us into night marches around the house looking for a ball point pen or a barrette. The more banal the object was, the harder we looked. She growled and shouted just knowing we’d “done something with it”. We stumbled around looking in coffee table drawers (again), around the tchotchkes on the mantle (again and again), and under the couch (again, too many times to count), barely able to keep our eyes open. But, I began to think: you know, maybe I had taken the pen or barrette. What’s remembering got to do with it? Maybe I blocked it out. I’m so bad I don’t even remember my crimes. Mom sure seemed convinced that I did it, so I must have.

This truth made it easier to take her beatings and silent treatments. I was never as clever as my brother, but I’m stronger. I could take as good as she could give. So, I did solids for my siblings. Somebody had to. I took the blame for their fuck-ups. What’s the worst she can do to me, I asked myself. Kill me? Whatevs. I was absolutely unafraid. The more I stared her down, the harder she walloped. Since that didn’t work, she went in harder for humiliation. She came into the dining room once, tucking her flimsy worn robe around her naked body (I saw far more than my fair share of Mom’s nethers), and caught me having a bowl of cereal: “Eating again, dummy?” she said. She slid over to where she kept the Southern Comfort over the kitchen sink, poured herself a shot, and disappeared back upstairs. The more she hit me with that paddle, the more alive I felt. I relished the attention and the ferocity. Sometimes, we both forgot that she was beating and that I was being beaten. We bonded. The clock ticked. She’d stop, the paddle in mid-air. And, a bit dazed, shake the paddle at me: “And don’t do it again.” On a road trip once, I asked Dad how he could have left us with someone so mentally ill. He said he didn’t know what else to do. All of this opened a vein of shame in me that has never run dry. I hide in plain sight. I’m present but you’ll never see me. Visibly invisible. Shame, my spine. Rage, my blood. That kept the ship afloat. Or, so I thought.

An insurance salesman, Dad spent long hours with the families of clients and doing volunteer work for the American Legion. When he was home, God bless him, he would sometimes take my brother and me (and often a few scouting friends) on twenty-mile hikes where we’d sleep in a barn or, if it was winter, set up camp in the sub-zero temperatures. He later told me that the effort those hikes took was nothing compared to the effort it took to stay home with Mom. When he was home, his routine was to work on some outdoor project (usually involving the rototiller, which had him tangling with a roaring machine chewing up the earth and tomato worms) and then gorging on a whole gallon of Quality Dairy butter pecan ice cream, getting stoned on sugar and heavy cream watching Sunday Night at the Movies. Until very late in their lives, my parents couldn’t get it together to spend time together.

We all developed different strategies to cope with the centrifugal force of our anger. Dad stayed away. Mom stayed up in her room sipping Southern Comfort or in the basement watching the washing machine spin. She nailed me and my sisters with the flat, ceramic tile side of a cheese paddle, but my brother with the straight edge. He played dead on the sidewalk, began sexually abusing my little sister, and disrupted his classes. Mom’d beat him into a corner with the hard edge of her paddle. He’d cover his face, sob, and beg her to stop. She’d take a step back to get a good look. “Get up,” she’d tell him. “It doesn’t hurt that bad.” Afraid that he would hit her, he moved out at fifteen, started drinking, and hasn’t stopped yet. The night before she died, he stole her wedding ring — the one thing she wanted to be buried with. Maybe he hocked it. Paybacks are hell. By the time I was a teenager, mens’ rooms were my playground. Urinals weren’t just for pissing.

Testing Positive, or Madonna in July

At ten, an older boy scout I worshipped slammed me into a church wall telling me to suck it suck it suck it. His cock smelled like pine cones. I ran. When I asked Mom to call the boy’s father and ask him to tell his son not to do that again, she turned from her organ practice and said to forget about it. At fifteen I let go of extra chunk by eating salad and cottage cheese for six months. The physical transformation changed my standing in the world. In my family, I became a superstar. Girls whistled at me. Men in cars slowed down. I had never been hugged by anybody in my family except my grandma sometimes. The attention weirded me out. I ate less. And started running. And shooting hoops alone. Over and over. And hitting tennis balls against a wall. Alone. By high school, the pieces of my life hung together on very thin threads. Somehow, I kept getting drafted onto prom and float committees and cast in high school musicals. I gave speeches touting Reaganomics and interned for a G.O.P. congressman. No matter how hard I tried, I could not tear myself from cruising the parking lots across from the gay bars in my ’71 Olds Monte Carlo. I was starving. I, and thousands of others, hungered and hunted along the walls and in the shadows, in the parking lots and the washrooms. I cruised guys at the Frandor Bookstore, got picked up by Triumph Spitfires on Cedar Street, showed up unannounced at the apartments of men with thick moustaches, and spent long hours huddled in my Monte Carlo idling in clouds of exhaust amongst hundreds like me. I ached for this distortion. I needed to be reworked and repurposed. I had to be anything but me. Between all that prowling, I tucked into the slopes on my high school lawn, reading the Russian acting teacher Stanislavsky and knowing it was only a matter of time before I lived the life of an actor, writer, and teacher. Unlike being gay, I knew full well by my late teens what being an actor would be like, and I threw myself into it. The Invisible Man’s got nothing on me. I can disappear in plain sight. Maybe I got infected then.

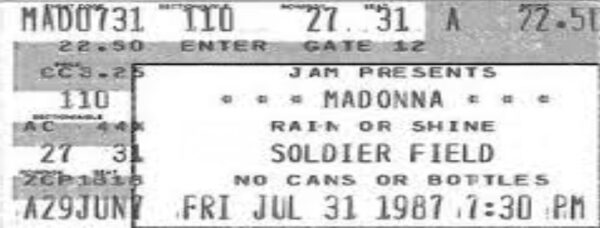

In a few years, I had made the front page of the local paper, winning Best Actor awards for playing the blind guy in Butterflies Are Free and Groucho Marx in the musical A Day in Hollywood/A Night in the Ukraine. Chutzpah gave me even more room to hide. I loved what I was doing. I started a union in a mob-owned shop. Hounded by death threats, but packing thirty bucks, I hit Chicago. There, I waited tables at an Italian bistro that first summer. Learned to party and make pasta with the owner, Giovanni, in his cream Armani suit. I wasn’t two months from my hometown mob guys after me before Chicago reporters started calling me asking if I knew Gio was wanted for the murder of seven Sicilians. I quit. I worked as a TV extra, soaked in the Art Institute, and started training to act. I ran Lake Michigan from Foster down to Oak Street, thumped to The Smiths belting “How Soon Is Now?” at the Aragon Ballroom, and hung out at the Green Mill on Broadway Boulevard. I did plays, learned how to have fun onstage, and had raw, unprotected sex with Z, a Syrian-Italian who fucked me against a tree. I fell in love with Billy, a famous artist, who called me a prude for only wanting to be with him. And then with a Cubano, Rafael, who liked me more when I didn’t talk. In 1987, when I was with Rafael, I got an HIV test for kicks. It came back positive. “You’re going to die,” the doctor told me. July 31, 1987. Later that night, Madonna belted “Live to Tell” on stage at Soldier Field and I hid in plain sight among 50,000 people.

Mom and Dad were the first people I told. Thinking he knew a safe bet, my dad took out a life insurance policy on me. He was the beneficiary but I was to pay the premiums. And I did. I decided to do everything I could to make it as an actor and live as high a quality of life as I could until my time ran out. I have the note I wrote myself to prove it. It didn’t matter. I was dead already. AIDS panic confirmed my worthlessness. Billy said HIV was a hoax and Rafael demanded a blow job.

A year or so after testing positive, I had found another oasis. A magazine emblazoned with “Living with AIDS.” I stopped in my tracks. Two muscle-bound hunks on the cover grinned at me. I circled the magazine rack, played it smooth, and inched closer. My heart thumped, my brow sweat. Talk about a paradigm shift. I’d never seen or conceived of “living” and “AIDS” in the same breath. A door opened and I flew through.

The bravery that went into ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) will never ever do it justice. What the ACT UP crew did in those years made me need to go big or go home. My plan was to just get as much living as I could for as long as I could and then just disappear. It never occurred to me that I would live. Even as ACT UP began their own Treatment Action Group, stormed the Centers for Disease Control, took over the Food and Drug Administration and National Institutes of Health buildings — I could not waste time. While the world panicked, ACT UP were (and are) unstoppable; and gave people like me a leg to lean on. The more the U.S. government denied AIDS, the more ACT UP and other groups had our backs. In 1986, the first treatment for AIDS, AZT, was introduced. With over 50,000 people now dying in one year, AZT was a hope against hope. But it killed.

In 1988 my brother, Mike, asked Susan, a single mom with two kids, to marry him. She said yes, but her marriage blood test came back HIV positive. Mike tested negative, yet refused to dump her. She had gotten the virus through blood transfusions during cancer treatments in the 1970s. Mom counseled that Susan and me were threats to public health. We belonged in concentration camps. She wasn’t alone. The American government had abandoned HIV-positive Haitian refugees in tent-towns at Guantanamo in Cuba without treatment or support. That threat has dimmed perhaps, but it remains real. Even in the U.S. Not so long ago, Kansas state legislation called for the containment of HIV-positive people in an “isolated environment and their movements restricted”.

In those days, antibody tests were unstable. Susan and I tested positive — and then negative. Positive and then negative. My parents broke the bank to get Susan onto AZT. It was not offered to me. To be fair, it never occurred to me that they should. I presumed I was already dead, but I kept living. At night, Susan was wracked with violent coughing. I can still hear it. She called me from a room where medical personnel had locked her in to breathe a medicinal vapour. “They’re in spacesuits,” she whispered from a phone in the room. “They won’t even come in here with me. They’re just watching me through the glass. Why won’t they come in?” We were both pinballs ricocheting between tests, results, advancements, reverses, falsifications and the one endgame we presumed was in store. Six months after starting AZT, Susan tested negative — and then died. Naturally, Hollywood called.

Dead Man Walking

Back on the mountain, the iPhone assured me that the path was just above. As I climbed the zig-zagging path, bits of brick and dried earth crumbled. I slipped, recovered my footing, and slogged on. Now higher up, a clump of bushes blocked my way. I dodged it, but the ground gave way, landing me flat on the slope at forty-five degrees. I snatched at a handful of branches. Thorns. Climbing, I lunged for grasses and roots. I’d get a footing and check the phone’s map. Ten feet and I’d be back on the path. For sure. The temperature soared. A few feet farther and the path disappeared. A yard or two past that, the ground caved. A cavity opened under my feet. Rocks and dirt echoed as they hit far below inside the slope. I leapt, grabbed at grass, stones, dirt, anything. I’d get a leg up and that ground would give; down I’d slide. Only to leap again, land a little further on, snatch and pull. I pressed my belly into the now almost vertical slope. The path had to be only a couple of yards farther. I felt for the phone. It was gone. My throat seized, my eyes stung. Wiping my face, the arm came back bloodied. Face, arms, hands, and legs were slit by thorns. Encased in dense bush, I clung to the slope. Sweat and blood blurred my vision. Do not panic, I told myself. Squinting through a lace of leaves, I glimpsed a strip of blacktopped road twisting off and out of sight. I spotted the phone in its Velcro sport case, dangling from a bush a few yards back. With a grip secured by grass, I leaned out as far as I could and snatched the phone. I was not making Portbou.

Then, I saw it. A rectangular patch of grass poking through the bush behind me but down twenty or thirty yards. The blood spatter and sweat stung. Fuck. With the phone in my teeth, I took hold of the thorn bushes. Spears slit my hands. I pulled myself as if by rope. And made it. Smaller than my desktop at home, I perched on the island on the mountain, I caught my breath. In swarms, bees zipped in and out of the thorn bushes. I heard footfalls far above. Runners. I leapt to my feet and yelled. I banged my water bottle in the dirt. I waved my baseball cap and hollered. And listened. Nothing. I screamed until my voice cracked. I’m here, I shouted. Help me. The bees droned, the thorn bushes shivered. To the south, towards Spain, purple clouds were rolling in. The sky darkened.

I eased the legs of my hiking pants over my bloodied calves. I took a bite of sandwich and had a sip of water. As long as I didn’t fall into a cave, I could survive. I’m an Order of the Arrow Life Boy Scout and have no problem camping outside in minus thirty-degree conditions. The first drops fell. I checked my phone. Two battery bars left. I called my guy. “Honey, I’m in trouble.” At his desk in Toronto, he kept his cool. God knows how, but he called the tourism office in Banyuls-sur-Mer; they wanted me to call them with my location. Ha. Like I knew where I was. The call to the bureau didn’t go through. I hung up. The footfalls above had been thunder. Those clouds, their purple now tinged black, piled in. The wind kicked up. The raindrops became a deluge. I put up my little University of Toronto umbrella as gullies opened around me. The patch of grass held firm. Protected in the bushes, the bees thundered. After the rain stopped, I closed my eyes. And listened. The bees hummed, the wind whipped. I had really done it now. No getting out of this one.

But, long after that storm cleared, a thought dropped in: things change. The thunder came — and went. The storm, too. Benjamin climbed this mountain dragging that suitcase. He came and went. Change is the one universal law. If I sat there long enough, eventually things would change. They have to. Just sit there. They will. So, I sat. I sat. I sat. I was drained. Beyond feeling any sensation of exhaustion. No panic. No drama. It is what it is. What would be would be. After a while, Benjamin’s old angel dropped in.

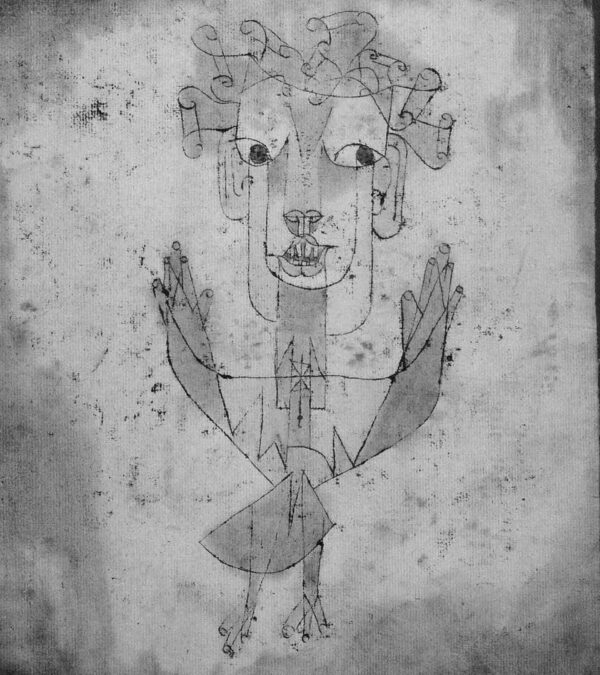

In one of his last essays, On the Concept of History, Benjamin wrote of a watercolor by Paul Klee, the Angelus Novus (New Angel). This angel is caught in a storm — the storm of history, the storm of progress. The angel beats its wings against the wind and rain. Its eyes are frozen on the past, but it is being blown into the future. At its feet is debris; the wreckage of history piles high. These remnants are traces — the sensualities (objects, textures, sights, sounds, tastes, experiences; things said, things not said) to which memory attaches. We artists get in among that debris to disturb it, rearrange it, and allow for new meanings to emerge. And the progression of history.

On the mountain with the bees, it came to me that I was part of that progression. That my landing on this patch of grass was one part of a change, a motion, a movement in process. If I got up, I would attach myself to that train of change and be pulled along. But the train could pass. That’s fine, too. Another would come. And, eventually, another. No problem. No worries. But, look, one train is as good as another. I can be fucked sitting here or fucked falling into an underground cavern. But change, it seems, had already caught me. If I moved, at least I had a chance. I got up. I stretched and surveyed the area. Beyond a curtain of thorn bushes, I saw a low-slung wall. Same as HIV. If I could hang on long enough, I might have a chance.

Susan’s cry for help from inside that sealed room isn’t so different from the daily effort I have made to reach solid ground. Around the time Susan died, my acting career took off. I did the lead in a movie in Mexico, booked a big Hollywood movie, and moved to Los Angeles. I booked one sitcom, and then another, and another. Features and TV movies came my way. Me and the brilliant Brett Butler shared smokes while we both got shit for bringing our own kind of funny. I split Patrick Swayze’s lip, he my forehead in a fantastic fight scene. The ship was in rough seas. I ran. And ran. I’d hop the fence at Hollywood High and run the track nine miles or more. Take the Hollywood Hills from Griffith Park over to Burbank and back; farther and harder; steeper hills and rockier paths. I stayed healthy and did wheatgrass. I wrote, directed, and booked more acting gigs. I co-founded an arts education organization and discovered my love of teaching. By then, the ship leaked. The more jobs I booked, the more shame ate at my insides. Getting a job became a cruel indictment. A cage match of my own worthlessness. With no way out, I grasped the thickest root I could find: philosophy. Even while I was on location shooting films, I made my way through Aristotle, Kant, Leibniz — you name it. The pre-Socratics and Heraclitus lit the way forward. My life changed, I found Perception, Metaphysics, Ethics and Logic — and home. I found my voice, graduated summa cum laude and never looked back. This seemed a patch of earth to stand on.

Back on the mountain, I headed for that low-slung wall. The rain gone from those slopes, a cloud of bees lifted out of the bush to surround and cocoon me. Oddly, I wasn’t afraid. What’s the worse they can do, sting me? Whatevs. I did not look down, right, or left. I slid under a thrush of bush to a low wall of crumbling and root-eaten bricks. As near as I could tell, it was a twenty- or thirty-foot drop from where I stood to the next perch below. That wall took my weight just long enough before it crumbled to give me a bird’s-eye view of what a jump might entail. Between me and that perch below was a wall of thorn bush. I’d have to leap over. I’m no Michael Jordan, but if I sprung as high as I could maybe I could clear the top branches and roll down. If not, I would die up there. I’d take my chances.

The bees thundered.

I leapt. And hit, rolled, and slammed into another wall below. I had landed ten feet above the vineyard I’d first climbed up into. Dizzy and shaking, I lowered myself down into those vines and stumbled on. In minutes, I was on that blacktop road I’d seen through the leaves. And right there, a hundred yards from that patch of grass above, a family of vineyard workers ate their lunch on the flatbed of their truck. A man chased a little girl. A woman nursed a baby. Bloodied and shaking, I made my way back down to Banyuls-sur- Mer. After a few beers to steady my nerves, I hopped a six-minute, 1.89-euro train to Portbou.

Exile

God knows, I have leapt my share of high- and low-slung walls. Being a closeted queer and HIV-positive working Hollywood actor is not for the faint of heart. The bigger the job and the bigger the paycheck, the worse it got. On set, I waited to be fired. Off set, I ran the Hollywood Hills, directed theatre, taught a million workshops, worked on my arts education initiatives, and dog-paddled for my life. And then I fell in love.

V. wasn’t the first person I fell in love with in L.A. (I’m a lover man) but in keeping with my spotty track record, I’d taken a four-year break. When I came out to him as positive, he came out to me as out-of-status. He was on his way back to his hometown in Africa to go back into the closet. To be out in his country meant certain persecution and likely violence. But chutzpah mixed with trauma gives guts — and, oddly, knowing. I knew we would get him to safety. I did not know how. It took years. Being experts at the game, we hid in plain sight. We told only a few friends of our situation. I moved country three times and ran a million dead-end roads.

To be rejected by one’s own country is to land on another mountain; in yet another sea of confusion, disorientation, and terror. Never knowing if today was the day that Bush’s I.C.E. would knock on the door and disappear my guy. It happened to thousands of others, why not us? As hundreds of hipsters gathered to wave their fists and chant “USA, USA” on Hollywood’s Franklin Ave. post-9/11, we, and thousands of other bi-national same-sex couples like us, sought escape routes. One went like this: we hired a lawyer to get my French-speaking very talented partner into Canada on a skilled worker visa. Miraculously, I got into a Canadian graduate program in Philosophy. I moved to Canada thinking my partner was right behind. But our American lawyer ripped us off and failed to file V.’s application — twice. Fearing for his safety, I moved back to L.A. We stewed for a year until our newfound Canadian lawyer told us about a safe house in Buffalo and, after a nail-biting border crossing, and months on tenterhooks, V. was granted asylum in Canada. He got into the country, but not me. Turns out, the two people in this world almost no country wants are an HIV+ person and an African. I returned to L.A., wrote a novel, and finally took a senior theatrical management gig in Canada — which earned me a work visa to stay in the country. Out of fear of it all falling away, I clawed away at sixty- and eighty-hour weeks. But this was not solid ground. The earth gave way: I fell through and collapsed the same day I signed my first book contract. V. found me unconscious in a hot bath. Incredibly, he says I went straight back to work and even delivered a talk on pedagogy at Western. That isn’t work ethic, that’s dog-paddling. For my life. And then I slept. For months. The diagnosis was a “brain event” not directly related to HIV. But, I knew the deal. My CD4s were 38 (normal is 500–1500). CD4s are T-helper cells; the backbone of the immune system. Indefatigable, I edited my book. Exhausted, I went on medication. The book launched, got great reviews, and off I went on tour. Running for my life. Move. Move. Just when I thought I had slipped from that noose, an animal rose up inside of me gnashing its teeth: it was time for me to go. The jig was up. Give me a kiss from my guy and the smash impact of a semi-truck’s steel grill. I wanted it.

Terra Firma

Several years ago, police broke down the door to the house I grew up in. They found Mom stuck in a chair. She’d been there for days soaking in piss, shit and delirium, her knees too rotten to reach the phone. When they found her, Mom’s looked to the EMTs grinning. Bliss in a sea of paper, dead animals, empty peanut butter containers caked with yellowed noodles, and dried tomato sauce. Various family heirlooms — hand-tinted portraits of her parents and my dad’s mom — tossed into a pile with the same care as the hundreds of Republican National Committee donation asks. I’m not so sure I sunk the ship. Maybe the ship sunk itself.

Benjamin’s angel promises a transmutation of what’s come before. A few years ago, I visited a young naturopath who had no idea that once there were no effective treatments for HIV. For a long time. Her not knowing is my fault. In part. Shame shut me up and shut me down. If I don’t speak, how would she know? That people became skeletal almost overnight; that they started missing work; had a few hospital stays; then cashed out life insurance policies; and — disappeared? She hadn’t heard Susan’s cough or her terror. But, I’m still here. If I don’t let her, and you, know what it was like, then who is? Susan’s dead. Billy’s dead. My Arkansas cousin — too. 39 million and counting have dropped off. 37 million are living with HIV right now — many without guaranteed access to treatment and medicine and often criminalized. If not me, who? You have to know that a plague came with no directions and saved my life. Everybody’s got their HIV. All we got to do is take the next right step.

Photo by Denys Nevozhai on Unsplash.

Read more