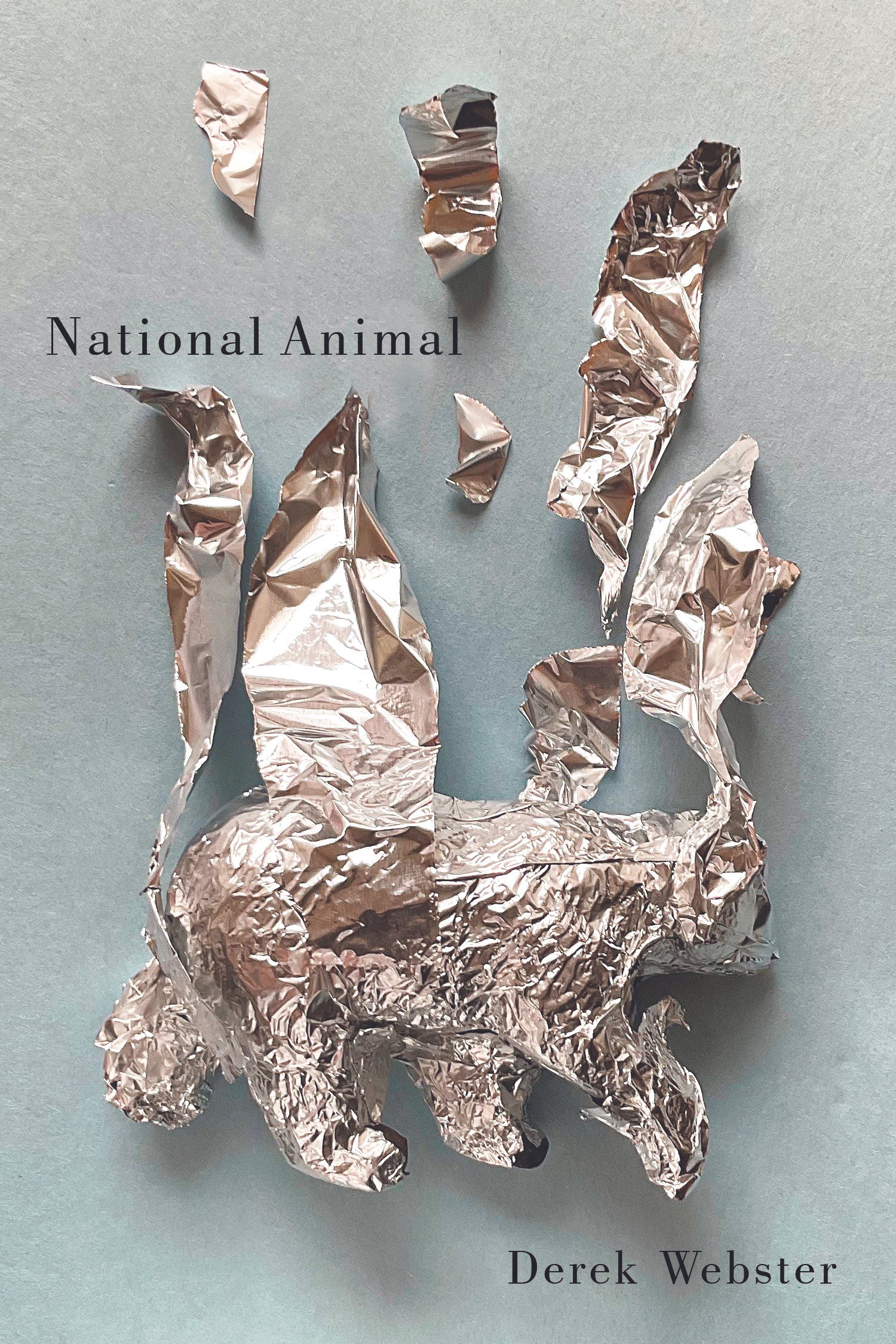

Under Review: Derek Webster’s National Animal

By John Vardon

Derek Webster’s name is not new to the editors of The New Quarterly, his poems first appearing with us in the Spring issue of 2000. Nor is it new to the editors more than a dozen other literary magazines and anthologies in Canada and the United Kingdom. He is also an editor himself, most notable for founding Maisonneuve Magazine. In an online interview with John Wickham of the Quebec Writers’ Federation, the poet said that his first book (Mockingbird, 2015) amounted to a personal reckoning but that National Animal was more of a national reckoning. That reckoning does indeed take place on a much broader moral scale, involving cosmological considerations in its final sequence.

The challenging thematic scope of these poems is reflected in the poet’s adventurous approach to form and style. He gives us sonnets, free-verse poetry with various stanza configurations, and one poem, “Naught,” which uses traditional terza rima the with ironic effectiveness. The three boys make off with the what’s left of a manse burned to the ground, because for them “Out here, there’s naught to do/but wait till God’s will cools, then rend/a use from what can’t last.” There is a also a variation on an ekphrastic poem, “An Old Painting of Charleston Harbor,” in which the speaker asks in regard to the man and boy depicted in the scene, “After two hundred years, if/these/ deft shapes—head/thrown back/arm raised—seem to cry/ out from the shore off their captured world/who hears them?” For readers who have forgotten (but shouldn’t have), the poet points out in his “Notes” that the port was prominent for its slaving activity. Webster’s adventures in form also include the prose poem, “Blanche Dubois at Mercy Asylum,” in which the poet takes on the voice of the protagonist from Tennessee Williams famous drama after she has been living in the asylum where she was committed at play’s end. Now back mentally from the fantasy world into which she retreated after her assault, thanks, she believes, to electroshock therapy, she now possesses a lucidity that makes intolerable the mind-numbing routine of the institution, where “the days unspool at the sewing machine/in the kitchen the garden the latrines” and where the patients “are either on duty or old biddies rocking in chairs.” She is part of a very mad world, witness to and perhaps victim of the asylum’s cruelties and abuses. As she realizes that the only means of escape involves a brutal medical procedure, she once again consigns herself to “the kindness of strangers.” Webster emphasizes the non-stop intensity of Blanche’s internal world by eliminating all punctuation, most notably periods.

As befits the moral reckoning at the heart of this collection, the tone of these poems is often serious, admonitory, but this book is not all regret and reprimand. One of the most enjoyable is “Homemade Blueberry Wine,” which is wonderfully funny, in contrast to the grief and grievance which characterize so much contemporary poetry. I would say that it reminds me of Al Purdy’s “Homemade Beer,” but confessing a knowledge (or worse still, an admiration) of that poet’s work is, in some editorial circles, tantamount to confessing a love for the verses on Hallmark greeting cards. Less comic but just as amusing is the sustained sarcasm of the five sections in “Dominion,” the last of which begins, “Our canoe keeps sinking/Something inside is too heavy/flowing in and out when seasons change/escaping all our frantic bailing.”

The sad state of our nation is reflected metaphorically in the title poem; It presumably refers to the poor beaver, which “chews up the book/of what it was…gnawing/ on itself, surviving on its wiles.” Equally metaphoric in its intent is “The Writing on the Wall,” which literally describes the efforts of a city worker who erases the ever-proliferating political and sexually suggestive graffiti on a Montreal building but symbolically suggests our willingness to forget dissension and unpleasantness, in keeping with the poet’s intention, stated in the interview mentioned earlier, to address “the gap between wishful thinking and what is actually going on.”

The final section of the collection, “The Thinker,” moves from the confines of the earth to the vast reaches of the cosmos, from the Big Bang to the universe’s end. Inspired by Wallace Stevens “The Auroras of Autumn” and informed by concepts in theoretical, experimental, and particle physics, with titles like “Singularity?Genesis” and “Entropy/Language,” the poems juxtapose these concepts with human development, the images and allusions centred on earth, as in the last poem, whose title is a nod to Douglas Adams’ novel The Restaurant at the End of the Universe. One of the most impactful poems in this section is “Movement/Contact,” which refers to the recordings sent into space on Voyager 1, in the hope that one of the civilizations hypothesized in Frank Drake’s famous equations on the possibility of extraterrestrial life might find them and respond. But the poem ends with a warning: “whoever we meet out there, along highways of dark matter or lonely spots between stars:/may they not do to us what we have done to ourselves.”

To hear that Webster’s editor at Signal Editions is poet Carmine Starnino is to expect poems with a distinctive style, precise imagery, and some sense of poetic heritage, and that is exactly what we get here. Let me end by returning to what he himself has called “the poet’s difficult task: to sing in ways that alert readers to what is important and unite people in a shared experience.”

Photo by Derek Otway on Unsplash

Read more