Finding the Form with Anastasia McEwen

By Anastasia McEwen

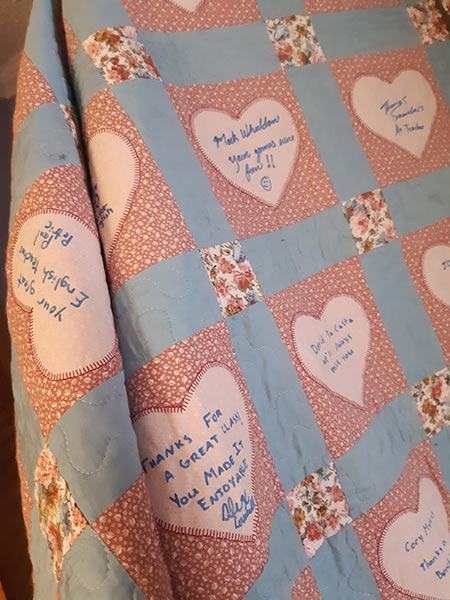

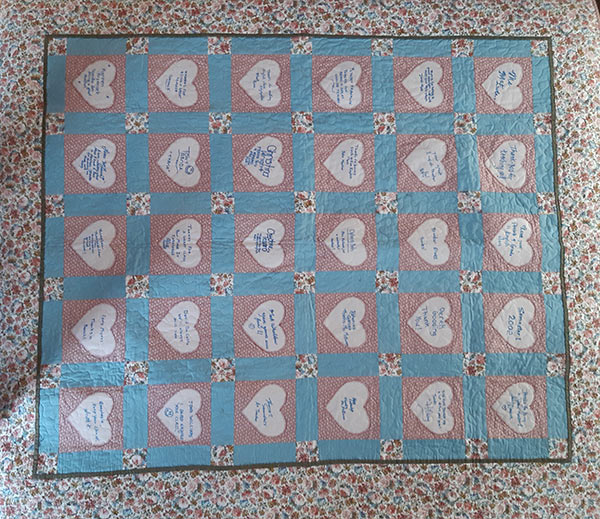

About a year ago, I received an unexpected visit from the parents of a girl I had taught in 2004. I invited them into my cramped hallway, thankful the dim lighting masked all the mitts and backpacks piled along the wall. They stomped the snow off their boots and smiled at each other with a glance that said wait till she sees this! The woman pulled a folded quilt out of a plastic bag, spread it across her arms, then let it drop to the floor like a stage curtain. Patches of blue, pink and floral were stitched between rows of pink hearts—each with a hand-written message from a different student: “Thanks a bunch,” “I really enjoyed your class,” and my favourite, “Your (sic) a great English teacher.”

The woman explained that she and her daughter Sarah, who now had her own family, had made the quilt for the baby I was carrying. The quilt was supposed to be presented to me on my last day of class, but when the baby died three weeks before my due date, it was shelved in a closet where it remained for sixteen years. The woman refolded the quilt and handed it to me, “We thought enough time had passed” she said, “You should have this.” Later that night, I too thought enough time had passed and started to write Anomalies, an essay about the still born infant I gave birth to so long ago.

Anne Lamott, in her essay, Shitty first Drafts, writes, “The first draft is a child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and then let it romp all over the place.” My first draft was less of a romp and more of a heavy trudge through wet cement. Anomalies read like a police report: First this happened, then this happened, then this happened. By draft two I loosened up and began to pry open the past. Around draft five I wove in a few disparate threads (the cat fetuses, the stray kitten, the serial killer tomcat). With each revision I added more reflections and flashbacks and casual asides, and before I knew it, the narrative had mutated into a braided essay, a bubbling sloppy braid with four strands and even more chaotic timelines that lurched and jolted from one event to another. At this point I closed my laptop and took a breather. I had to take a step back and fiddle with each section, on paper, until the structure was intact. This is, I think, the most satisfying part of the writing process, when the scaffolding is complete and I can finally move on to the fun stuff—picking away at those little details.

When I first started writing creatively, I’d comb through volumes of America’s Best Essays and Journey Prize Anthologies and study one sentence at a time, trying to crack the code: what made these prose glisten? I discovered how much weight concrete nouns could carry. Most of my memories boil down to physical objects so I try to utilize them in my writing. When I think back to the day I delivered the baby, I clearly remember the black gum spots on the parking lot pavement, the violent zigzags exploding on the monitor with each contraction, the unlit baby incubator beside my bed. Concrete nouns allow me to add sentiment without appearing sentimental.

I find there are myriad ways to leap into a story but few ways to exit. I wrote one overly- philosophical coda after another, trying to sum up the entire pregnancy. Finally I had to ask myself the big question: what would Flannery O’Conner do? She once wrote (I can’t remember where) that an ending need not tie up loose ends but simply bring closure to a story. So I veered in a different direction and concluded with an image of my dad in the barn, with a shot gun, waiting for the tomcat. Perfect I thought, until I submitted the essay to my writing group. Some found it a tad abrupt, others downright jarring. I put the essay away and re-read it a week later and realized they were right; leaving the reader with that image seemed gratuitous—it put way too much emphasis on a minor thread. In order to convey something like, time heals but you never forget (but in a less clichéd vernacular), I slipped back into the realm of the concrete and came up with two images: a purple bruise turned yellow and crocuses sprouting through the snow. At that point I was able to build my final two paragraphs.

Sending off a completed work is always uplifting, but this time, when I clicked the submit button, I felt as if the last of a scab had broken free and dissipated into cyber space. Now, when I think back to that dark period in 2004, two other images comes to mind: a mother and daughter preparing a beautiful quilt, and twenty-six thoughtful teenagers writing a message to their teacher with a fabric marker.

“Anomalies” was awarded Honourable Mention in the 2019 Edna Stabler Essay contest. You can read it in the Winter 2020 Issue of The New Quarterly Vol.153. Anastasia McEwen teaches high school English and art in Guelph, Ontario. She was shortlisted for the CBC Non Fiction prize in 2018 and her short story, “Sea Girls”, was recently published in Grain. Her essay, “Standing on my Head Naked”, will be included an upcoming issue of The Antigonish Review.

Photographs courtesy of Anastasia McEwen. Cover photo by Daria Nepriakhina on Unsplash.