Finding the Form with Andrea L. Mozarowski

By Andrea L. Mozarowski

The writing of “Amphibios” has been a revelatory journey. Each step of the way, I was compelled to venture deeper into a post-war world which I first evoked in a series of Freefall writing sessions. In her reflection on reading submissions to the Peter Hinchcliffe short fiction contest, “Once to Admire,” Pam Mulloy closes with a nod to the (all-too-familiar) inertia that writers contend with when they “fight the urge to leave [the story] in the bottom drawer.” Over many years, I revisited “Amphibios,” retrieving it from its consignment there.

Written as an experiment, this Freefall weekly exercise I entitled simply, “Post-War London Chapter.” Inspired by Graham Greene, I used the Freefall precept of “write all of the sensuous details” to evoke a world that the reader might experience as intact and complete unto itself. The principal characters of my larger narrative were in fact Soviet Ukrainians displaced by the war, and not George and Joanna. But in this chapter, which I later conceived/rewrote as a standalone fiction so as to give George his fullest incarnation, I wondered what it would be like for a reader to encounter these refugees through a unique set of filters.

“I had to answer for myself the question of what he was doing during the war. In my heart I knew he had not seen combat. I went in search of historical possibilities.”

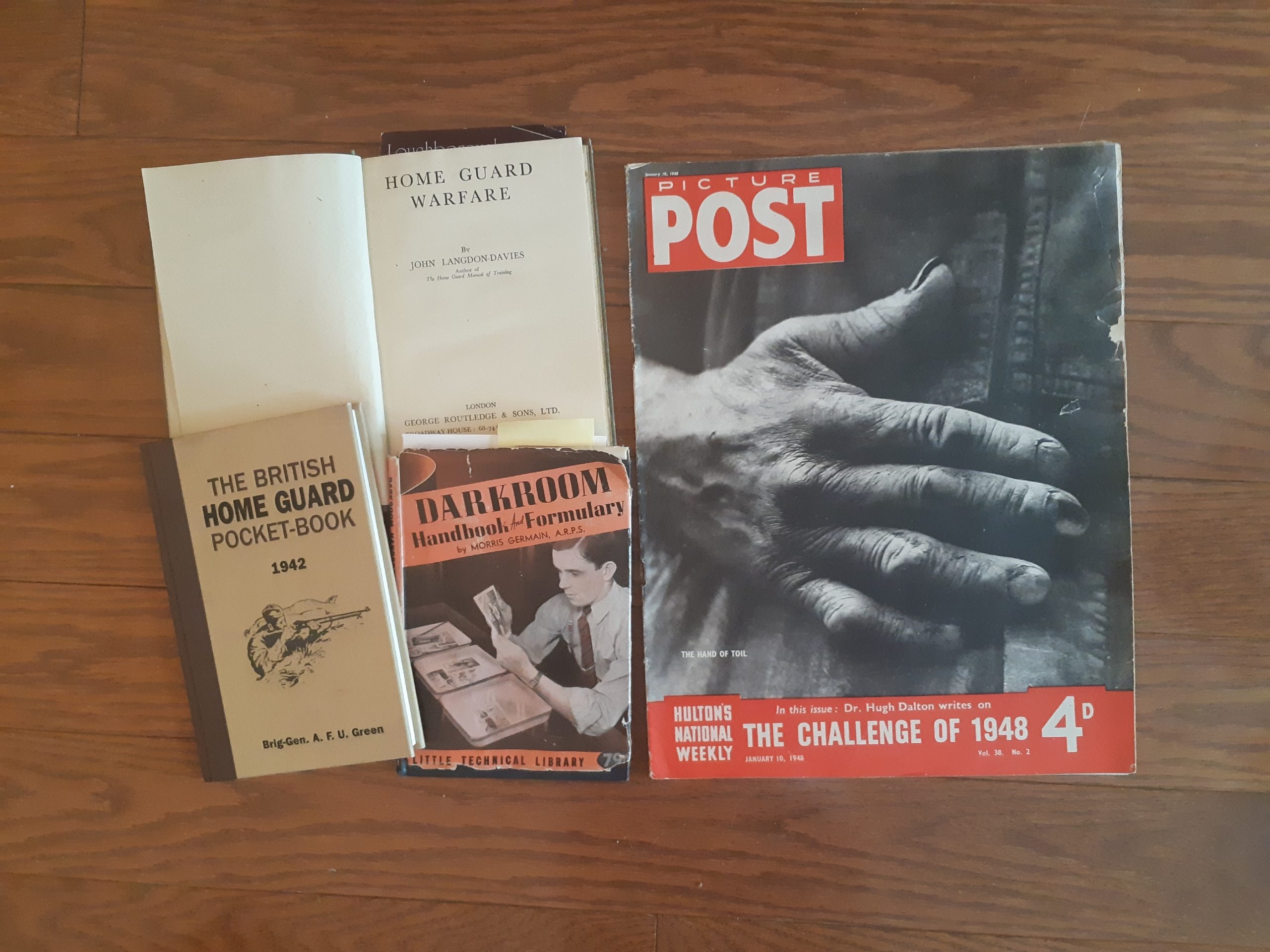

I drew my inspiration from lived experience and an anecdote shared by my mother. Growing up, I knew my parents only as sworn enemies. But once or twice, I remember kind words uttered by my mother: “In London, dad loved taking and developing photographs. The night he lost his camera – that broke my heart.” I had this testimony and albums filled with black and white photos shot and developed by my dad. I chose to build a story around this account and actual photos of the Daimler in procession and my mother in the park (Hyde Park I surmised), taken, I imagined, during my parents’ courtship.

The challenge then was to forge a narrative that wasn’t gimmicky and to avoid turning this inspiration of the lost camera into a clunky plot device that might move the story along but fail to move a reader. During a trip to London, I walked a portion of the route George’s cab takes and more recently consulted Laurence Ward’s Bomb Damage Maps 1939-45 to ensure that the routes George travels are plausible.

At a minimum, the Freefall piece was atmospheric and hooked me. Joanna sprang fully-fledged, as if from a god’s head. George became my biggest teacher, a character I patiently coaxed out of the shadows. As the protagonist, for a long time, he existed on the fringes of my imagination and the narrative’s time and place. I had to answer for myself the question of what he was doing during the war. In my heart I knew he had not seen combat. I went in search of historical possibilities. I learned about the Home Guard and as I kept digging, I discovered Osterley Park and the training of Auxiliary Forces (an Irregular Army) whose role it would be to stop a Nazi invasion on British soil. Continued inquiry eventually led me to an understanding of the role played by surrealists, chiefly the contributions of Roland Penrose (married to Lee Miller), in theories of camouflage and the instruction of auxiliary units in warfare. Penrose and John Langdon-Davies emphasized the mimicry of nature as foundations for concealment and observation (Robinson and Mills).

These underpinnings of imaginative participation in nature inspired me to evoke through the narrative structure George’s way of seeing the world. Around the time that I was making these discoveries I attended a workshop with Betsy Warland on “Writing the Between.” Betsy led us through an inquiry into the “betweenness” we were sensing or wondering about in our writing. In sharing the reasons she was inspired to offer the workshop she said: “Another thing that’s really powerful about writing the space of between is that it’s a threshold and threshold periods are very powerful periods in which things get destabilized. It’s a time when we get a lot of insight; in this state we can acknowledge a different point of view.” Betsy invited us to consider how the between was surfacing in our writing and thinking. As I worked with these possibilities I allowed material from George’s consciousness and unconscious to leak into the narrative. Eventually, I had to scale back on my ambitions because too many “between” spaces were disorienting for the reader. I had to be sure not to sacrifice unity.

While the overall narrative structure proceeds rationally, there exists a permeability within the container that allows us to glimpse George’s perceptions intimately, in an unmediated way.

I struggled with the ending and am still not convinced it’s right for the story. In previous drafts, the ending felt tacked on and anti-climactic. I found guidance in David Jauss’ “Returning Characters to Life: Chekhov’s Subversive Endings.” Jauss writes, “Chekhov tends to end his stories by returning his characters to life and the problems created either by their change or their failure to change.” He then goes on to illuminate ten of Chekhov’s strategies for forging “inconclusive conclusions.”

And thus, I sent my protagonists off in different directions to honour the brokenness and longing for love in both them, and their unwitting accomplices.

Andrea L. Mozarowski’s writing explores revolutionary spaces of survival for characters who experienced war on the Eastern Front. Reaching beyond polarities of love and hatred, liberator and jailer, she inquires, How can love begin again?

Photo by KAL VISUALS on Unsplash.