Finding the Form with Donna Seto

By Donna Seto

I started writing “Generation Congee” after my father was diagnosed with stage-3 colon cancer. My father doesn’t speak English. Or he pretends he doesn’t, especially when I’m around to translate. But I’m not fluent in Cantonese either. I’m pretty sure my fluency is equivalent to a three-year-old’s. People often ask how I manage to communicate with my parents. I shrug and say, “We make do.” Besides, communication is livelier with mispronounced words, misunderstandings, and awkward silences. This worked wonders during parent-teacher nights but was a nightmare during my father’s cancer treatment.

“Generation Congee” started to take shape during the silences we shared in the BC Cancer waiting room, or as I watched my father nod off during treatment, or when my anxious mother told us not to share my father’s diagnosis with the extended family. My parents have always been private people who used silence as a survival tactic and, during this time, I used this silence to write, to observe, to record the details of those around us.

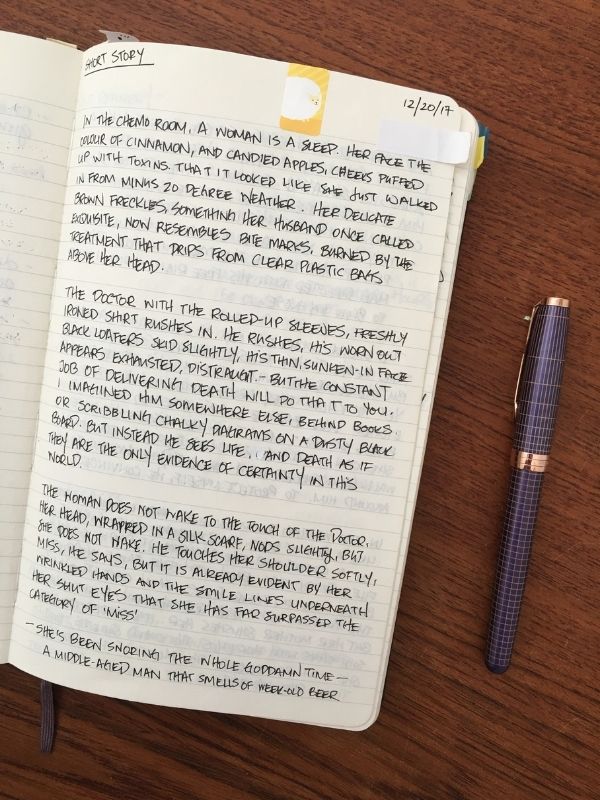

I started jotting words down in my notebook, recording the nervous energy in the waiting room, the shuffle in the oncologist’s walk, the openness of the translators. I wanted to make sense of this traumatic time – not so much to mark it in history, but more so, to understand my own conflicted emotions and struggles.

The story interweaves the present and the past, memories of my mother’s anxiety, my trip to rural China, my attempt to navigate the medical system and my own struggle with identity. There’s a sense of humour in the story, or my attempt at humour. Even the title where I use the word “congee” to describe my watered-down Chinese identity or “sing-sing”, which I assume means star, are shadows of my assumptions and misunderstandings that I have interwoven into the fabric of this piece.

This was always going to be a nonfiction piece, although since completing this one, I’ve started writing shorter pieces on immigrant experiences that are more fictitious. Whereas a personal nonfiction piece invites a writer to experiment with words, structure, tone and pace when retelling a real story, I found that fiction challenges the imagination and gives me the freedom to explore alternatives.

My work blends fiction and nonfiction. As an academic who was trained to write objectively, I initially struggled with writing fiction but now find that it brings me the most freedom. Nonfiction, however, especially personal essays such as this one, is unnerving because it’s personal. Too personal, almost. I can no longer hide behind convoluted sentences or theories that academics tend to hide behind, nor mask my true intentions through the actions of a fictitious character. A personal essay exposes the self, the self that was once silent, protected and hidden. But there’s a sense of liberation that comes with writing a personal essay or a memoir. At the very least, it de-silences what was once silent.

Donna Seto is a writer and academic from Vancouver, BC. Her work has been published in The New Quarterly, Ricepaper Magazine, and academic journals. Donna is working on her first novel and a collection of short stories.

Photos courtesy of Donna Seto.