Finding the Form with Heather Debling

By Heather Debling

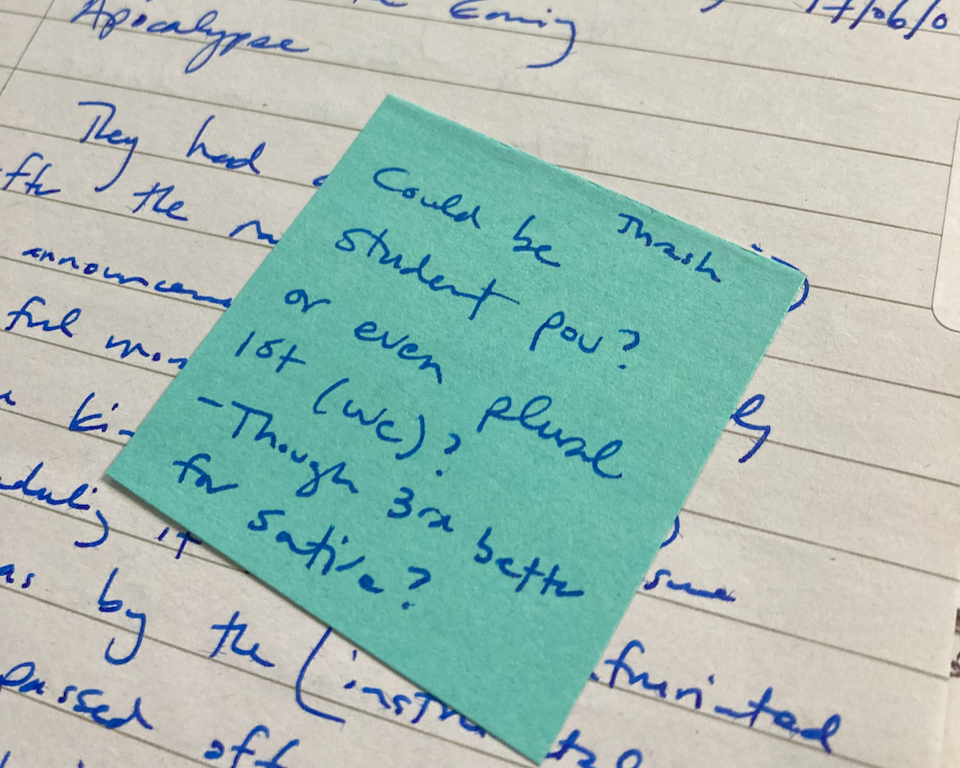

Flipping through some old notebooks recently, I came across the very first notes I made for the story that would become “Resilience.” The page is dated 2017, and there’s a working title of “Ms. Thrashings Grade (4s-5s?) Prepare for the Coming Apocalypse,” then a couple of paragraphs half-covered with a post-it, a scribbled note to myself about the possibilities for the voice (the collective we).

I distinctly remember the moment I had the idea for this story. I was working as an Assistive Technology Tutor, mainly with elementary students. Walking into a school one morning, I was stopped mid-stride by a question that contained a story: How would a teacher struggling with her own fear and grief about climate change prepare her students?

I probably wrote those initial notes in my notebook that evening after work. A couple more pages follow that first one, a list of possible apocalypses, one more short freewriting passage and then a list of descriptive details I could use.

And then there’s really nothing in my notebooks for the piece until spring 2019 when I decided to write the first draft.

That’s fairly typical for me. I have an idea for something, I do some initial writing in the first excited flush of that idea, but rarely more than a handful of pages. I might also make some notes, the barest bones of what the piece will become, but I don’t tend to start drafting right away. It’s usually months, but more often a year or two before I really start work on a piece, as was the case for “Resilience” and a previous story published in TNQ, “Count Your Blessings.”

“During a silent writing period, I sat at the desk, staring at the all too familiar blank page, fearing that again nothing would arrive. Out of desperation, I decided to write about what was right in front of me: some small, black, stick-like bugs. And there it was: my way into the story.”

When I did decide to write the first draft of “Resilience,” I remember it being a struggle to get started. A story usually arrives to me through voice, a voice speaking a particular first line. For this piece, I had a concept and I had the type of voice, but I didn’t have that first sentence.

There were a lot of false starts, a lot of writing sessions spent staring at a blank page or at the wall trying to will a beginning. Nothing seemed to be working. I went in that state of frustration to a weekend writing retreat. During a silent writing period, I sat at the desk, staring at the all too familiar blank page, fearing that again nothing would arrive. Out of desperation, I decided to write about what was right in front of me: some small, black, stick-like bugs. And there it was: my way into the story.

The rest of the story developed in a similar way. For the scenes set in the present timeline, the ones where the children are lost in the woods, I would go for walks around the river near my home, and some detail would catch my attention, and I would build an entire scene around that image. For the scenes from their past—the classroom scenes—they were also built on small details or images, but this time I pulled on my memories of teaching. Graphics organizers, a row of coat hangers, found object art projects, they were all very small, precise images in my mind that created the possibilities for each scene.

Rather than knowing the action and/or character development of the scene and mapping out the beats of the scene as I typically do—building a frame and then filling it in—I’d start with the smallest image and see what action could be built from that. In that way, the form of this piece felt much more organic, like the scenes grew in an entirely different and more natural way, a process that felt totally aligned with the story’s setting.

When I look back at the initial notes written in 2017, there’s not much there, but the essence of the story is. The basic concept, the theme of survival and what responsibility we have to others, the possibility of satire, and what has defined the story most for me: the first-person plural voice. As much as the story might change or evolve, the things that were fundamentally true about it, about the initial impulse for it, are still there.

And the morning I found those old notes? It was the day my contributor copies of Issue 170 arrived. More than seven years between idea and publication. When I tell the writers I teach and coach about it often taking 4-7 years for one of my stories to find its way into the world, I’ve seen their shoulders drop with relief, letting go—even momentarily—of the idea that we always have to go faster. Stories have their own timeline, and some of them take a long time to come into being, but I learn over and over again that their timing is always perfect.

Heather Debling is a fiction writer and playwright based in Stratford, Ontario. Her fiction has appeared in The New Quarterly, Agnes and True, The Antigonish Review, Room, and Tulip Tree Press’ 2021 Stories That Need to Be Told anthology. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia and is also a creative writing instructor, developmental editor and writing coach who helps writers embrace their unique visions and creative processes.

Photo by Feliphe Schiarolli on Unsplash