Finding the Form with Kasia Jaronczyk

By Kasia Jaronczyk

On the Value of Things

Every time I fold my pre-teen children’s laundry, their graphic t-shirts, colorful socks, bright sweatshirts, and remember their cute onesies and hats with animal ears when they were babies, I’m amazed at how beautiful their clothes are and how many they have. I think back to my time as a child growing up in the 1980’s in the Polish People’s Republic, where I had to wear my dead grandfather’s socks because there were shortages. My brother and I had only a few pairs of identical underwear that was difficult to obtain, (looking for separate styles for different genders would be impossible), two pairs of shoes – sneakers to wear in warmer weather and boots for the snow, and very few clothes that seemed to grow with us. In my childhood photos I am always wearing the same outfits: when I am very little, the sleeves of my sweaters are rolled up over my chubby toddler arms, and several years later, when I’m school age, it is the same sweater but the sleeves are three-quarter length on my skinny pre-teen arms. In even later photos, my younger sister is wearing it.

When I see my children’s toys, markers, crayons, notebooks scattered among discarded clothes on the floor of their bedroom, I wonder about the value of things. How some things do not have an intrinsic value, and that their value lies in how we feel about them. I don’t want my children to lack anything; on the other hand, sometimes I feel like they don’t appreciate what they have. I remember how excited and astonished I was when I received a pencil with an eraser on top one day. I had no idea such things even existed! For back to school shopping my parents made a trip to downtown Warsaw to a big department store and stood in lines to buy a few Chinese-made fountain pens, wax crayons whose marks did not peel on paper. The box had an elephant on the lid that I remember to this day. If we were lucky they would find scented erasers with pictures printed on them and magnetic closure pencil boxes – iconic items which can be found on a lot of communist nostalgia websites today. Even certain kinds of foods were special. The waiting for the Christmas or Easter feast with ham, sausages, different kinds of fish, oranges, and other rare items, was what made the holidays special. We often received chocolate, salted peanuts and oranges as treasured gifts. The foods which my children could have any time but don’t particularly like or desire.

A lot of people in Poland are sentimental about their disadvantaged childhoods where a lot of necessities were special, even toilet paper. There are several famous black and white photos from that time of lucky shoppers proudly carrying a wreath of toilet paper rolls carried across their torsos like a beauty pageant winner’s sash. However, there is a danger in that kind of thinking, the nostalgia for our communist childhoods that excludes the negatives. I was lucky not to experience any serious lack of food or other provisions, my parents did everything they could so I never felt hungry or cold. Because I was a child during Communism, I did not experience censorship or physical abuse from the military police or any frustration with my job prospects for the future. I did not have to struggle to provide for my family. The memories of my childhood are peaceful and happy, and do not reflect the economic or political reality of those times. It is very easy to forget that.

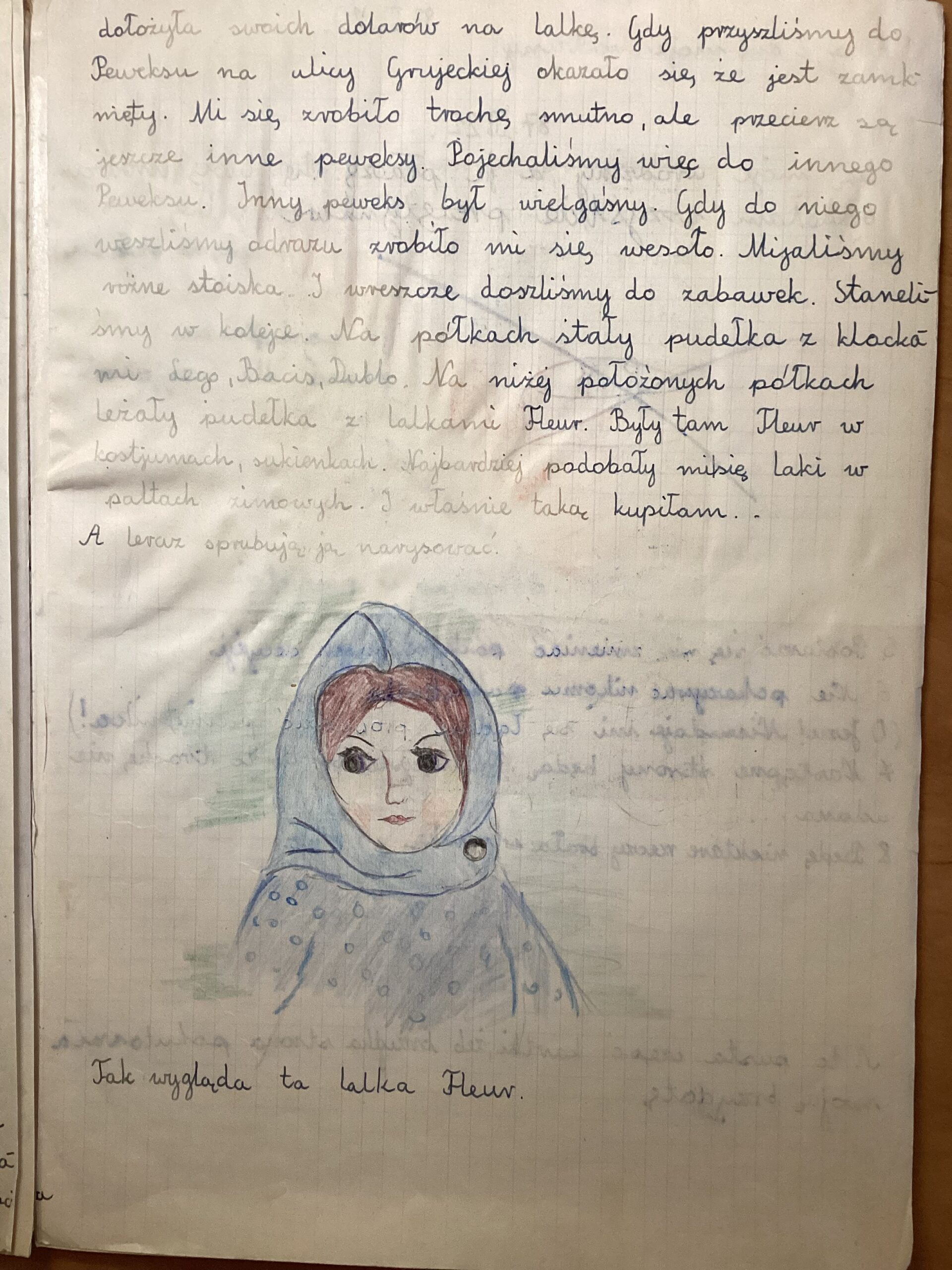

But there were a lot of things I hopelessly desired as a child, among them were toys that came from the forbidden West. One of them was a Dutch Sindy Doll called Fleur – a European version of the Barbie doll coveted by all the little girls in Poland. I remember I had longed for Fleur, kept asking for it for several on my birthdays, and was very disappointed year after year. I don’t think my children had ever waited longer than a couple of months for any toy. They don’t know what it is like to want something so much. There is value in waiting, in expectation and imagining what that toy and playing with it would be like. It was a long time until my parents were able to purchase it from Pewex, a special store in Poland where you could by Western goods for American dollars or special cheques from the government bank.

There are lasting effects from that kind of life – I have a lot of unused art supplies because I feel they are too nice for me to waste on bad art; nice clothes hardly worn because I am saving them for a special occasion that never comes. I collect different kind of dolls. Perhaps too many. I often look at my children with a strange envy when they carelessly rip open packages of markers or crayons, and immediately use them, the way they carry them outside, or leave in different rooms of the house where they often forget them. When they wear their favourite clothes every day unconcerned about staining or ripping them.

When last year Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie came out and people started talking, yet again, about Barbie and all the bad cultural stereotypes it represents and how it negatively affects young girls’ self-esteem I decided to write about what it meant to me. How the Fleur doll, along with chewing gum, Lego, and jeans epitomised the West, freedom and bounty. This again comes down to the intrinsic value and meaning of this woman-shaped doll. It is just a piece of plastic, but at the same time, it represents an unrealistic and unhealthy beauty standard. However, would a child playing with it notice this if she hadn’t heard her mother complaining that she looks fat, if she hadn’t seen photoshopped images of women in the media. The doll’s value should lie in its play possibilities, not in what it represents according to adult biases. For me, the doll’s beautiful wardrobe made me imagine my future outside the grey communist life and its deficiencies, in which I could wear something different every day and own more than just two pairs of shoes. The bendable legs and arms were features that made it come alive. I would never dare to cut my doll’s hair or paint on her with markers. She was too precious. I had only one.

To write this essay I looked through my childhood diaries in which I had written about and drew a picture of the Fleur doll when I had finally received it. On the internet I found photos of the specific doll I had chosen. I researched the details of how Polish people had access to the forbidden American dollar – the black market, and what the Pewex stores that carried Western goods looked like.

My Communist Barbie essay flows naturally from the memories of my childhood to my present when I watch my children play. I describe the moments from my life in The Polish People’s Republic that are parallel or opposite to my children’s, so that I could compare and contrast them in the essay. I included what I thought were interesting details from my childhood in Poland beyond toys and games but which coloured my childhood and were for various reasons memorable. Just like I’m doing it here.

And finally, I looked for the child that is still very strongly present in myself and how I connect with her in my life.

Kasia Jaronczyk is a Polish-Canadian writer. Her novel Voices in the Air is upcoming from Palimpsest Press in winter 2025. Her debut short story collection Lemons was published in 2017 by Mansfield Press. She is a co-editor of the only anthology of Polish- Canadian short stories Polish(ed): Poland Rooted in Canadian Fiction (Guernica Editions, 2017). Her short fiction was short-listed for Bristol Prize 2016 and long-listed for CBC Short Story Prize 2010.

Photo by Maksym Harbar on Unsplash