Finding the Form with Phoebe Wang

By Phoebe Wang

I am intimidated by the idea of a novel so I made myself believe that short stories would be easier. Short stories also fit my intention, which was to tell the stories of my community– the other mothers my mother met at the Chinese Community centre, neighbours, friends of our uncles and aunties, related through marriage, and my small, close friendships in University with the studious girls whose parents had emigrated from Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shanghai.

A thread of loss ran through all of the stories and experienced I witnessed. Heart attacks, football accidents, infidelity, denials, even a violent murder. I began to see a pattern in parents whose expectations and strict observation of professional and academic success, whose long working hours and absences from home would affect their children’s wellbeing and even drastically, their survival. These were stories I felt needed to be told, and had been told by others, but that I wanted to flesh out with additional implications.

For instance, a collection that had affected me as a student was Madeleine Thien’s Simple Recipes. In the final story, a father’s physical violence drives his young son into himself. I wanted to imagine what might happen to that son, and his sister, when they grew older. In Doretta Lau’s How Does a Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun?, I read of diasporic and immigrant twenty-somethings navigating Vancouver and other urban centres, weighted by ghosts and an inability to connect with others. How would these subjects act as parents, and reconcile their own emotionally distant childhoods and adolescents? Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife spotlighted the hopes and dreams of South Asian factory and salon workers and their comforts amid poverty and relocation. While my parents had also received social assistance, my stories and experiences were more about a tentative hold on middle-class, the accumulations of wealth and property that came from pushing children into professions such as law and medicine, and the racism and discrimination these Chinese Canadian families continued to encounter even as they rose in social status.

The idea came to me to show three siblings as they traversed the decades, each of them living in a different apartment or house. This form would underscore the temporality and impermanence of new immigrants still financially solvent, and the lack of stability that results from not having a sense of rootedness in a place.

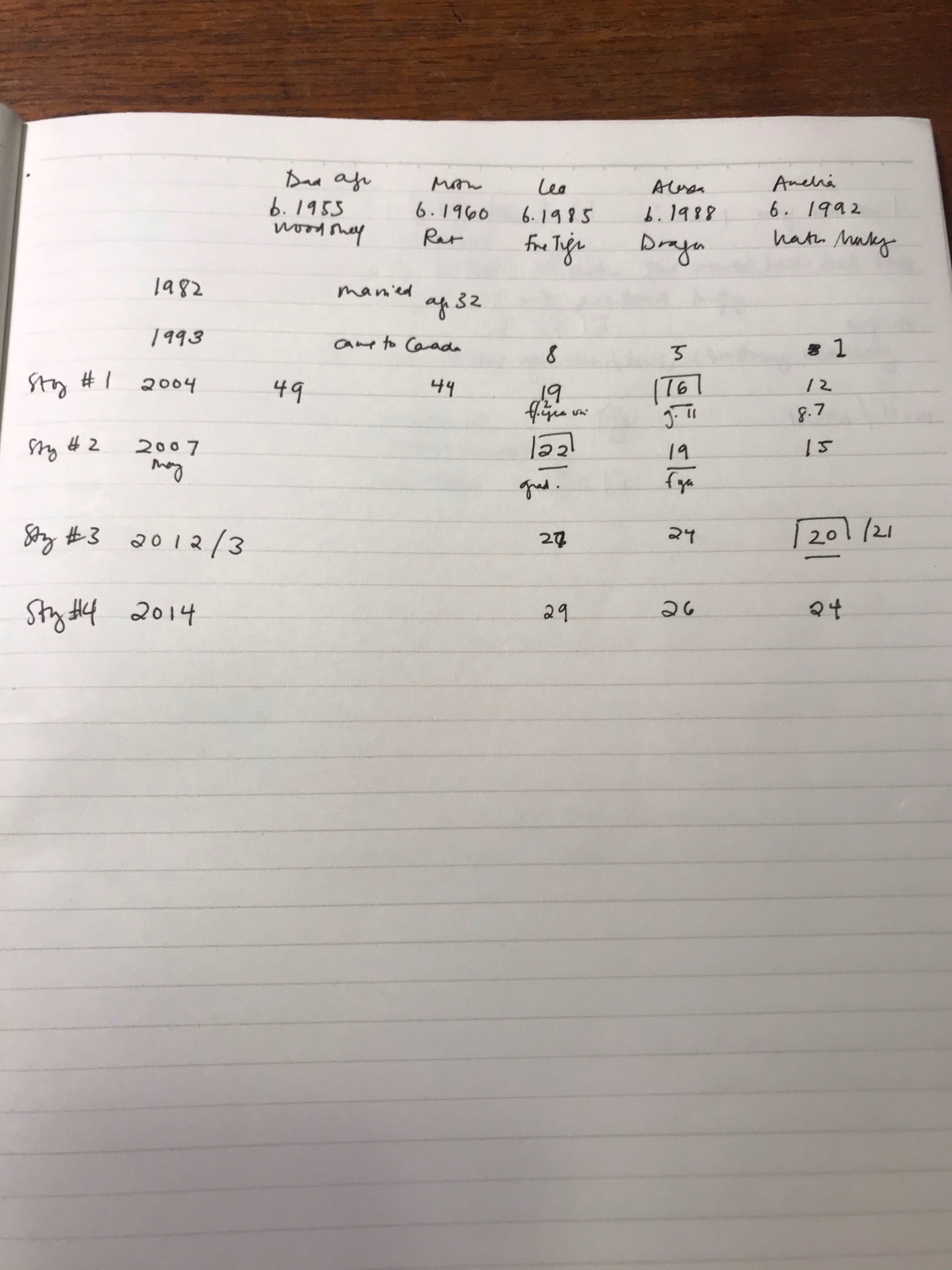

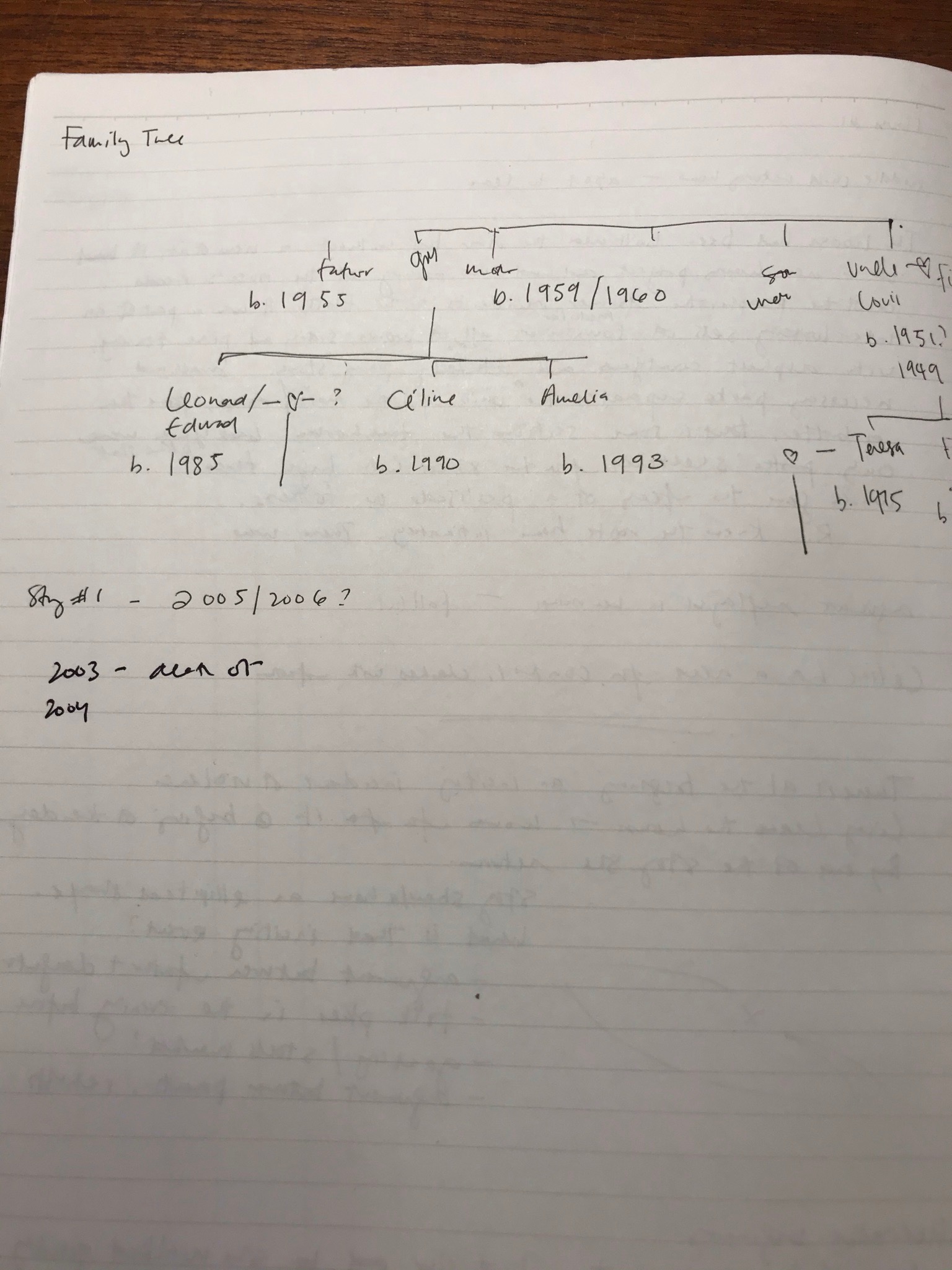

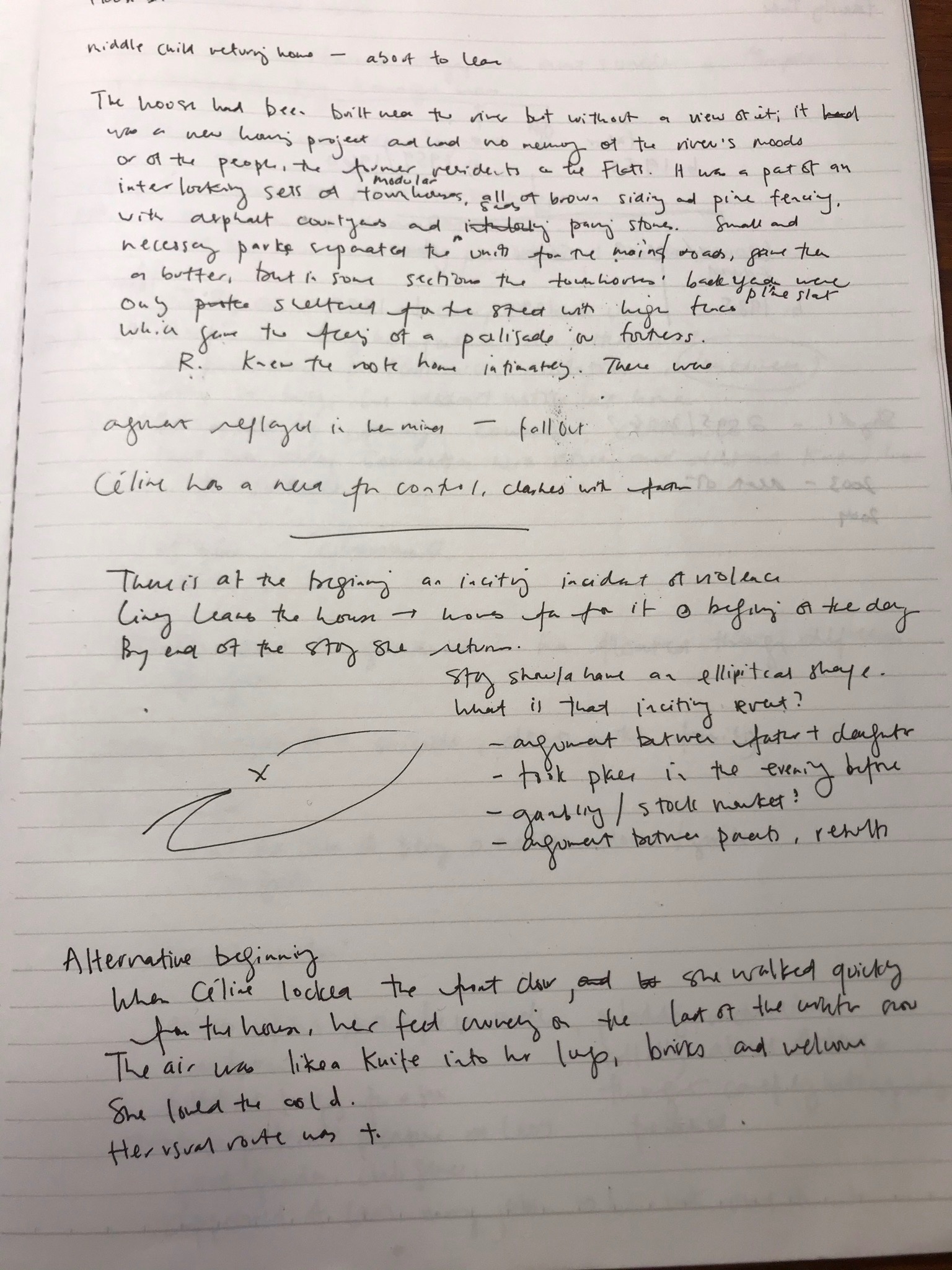

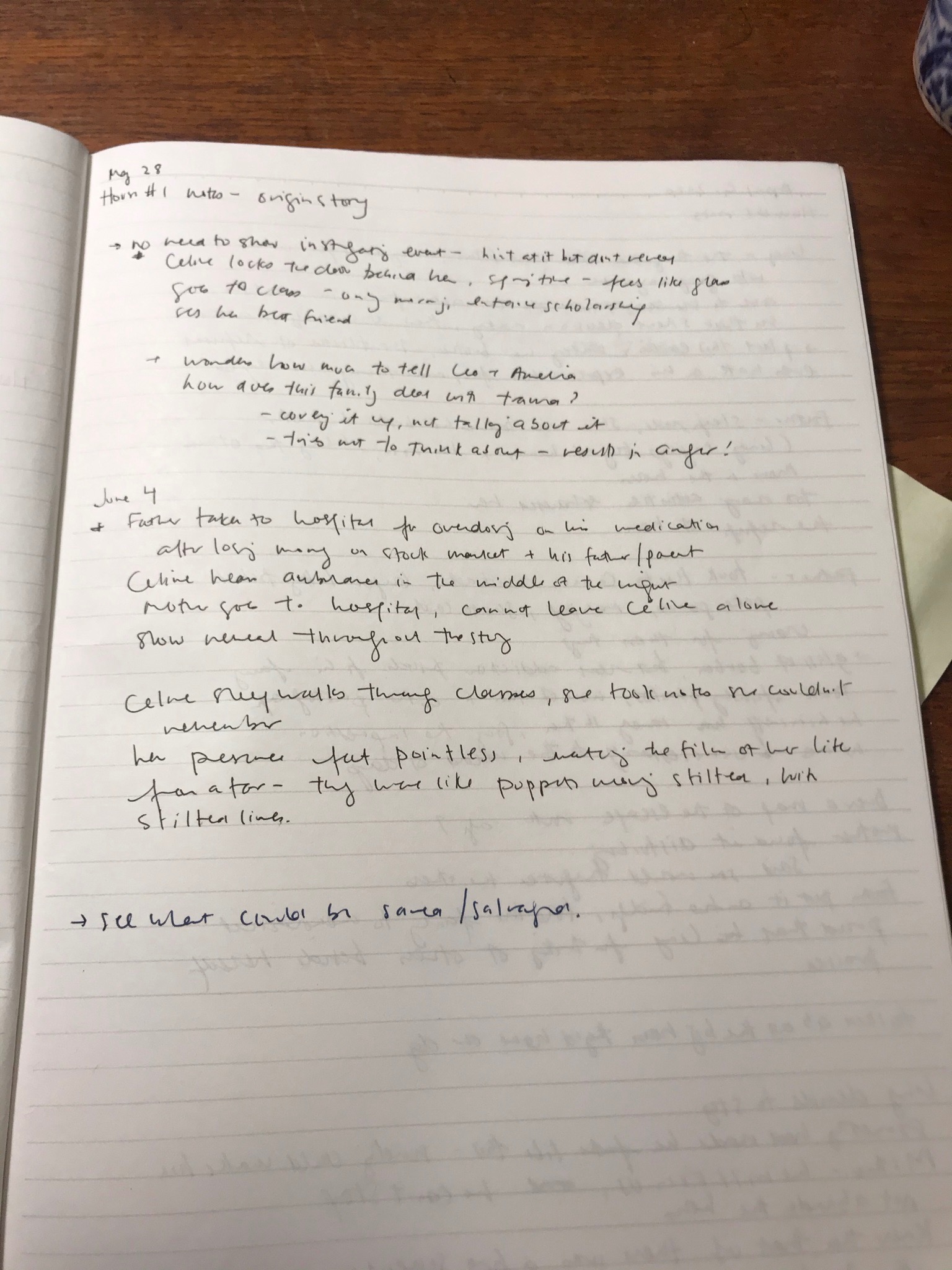

I set the first story in the family home, when the main character and middle child, Alexa, is still in high school. This story would contain the inciting incident that would further separate all of the family members. The father’s many emotional and physically ailments would reverberate through the years, affecting his children’s ability to form lasting relationships and find a sense of belonging. I outlined years and dates, drew family trees, aligned birthdates with Chinese horoscopes, even asked my mom to give my characters Chinese names.

It had been nearly twenty years since I wrote fiction. Having focused on poetry, I needed to relearn how to plot fiction, write dialogue and create characters. Fortunately, I had attended the literary program at Canterbury Arts High School in Ottawa, where we pumped out several short stories a year, taking a mechanical, formulaic approach. The key pieces of advice I remembered from our talented teachers was to alternate between action, dialogue and exposition and to contain the story in as short a time period as possible.

As a poet, I’m comfortable with containers and strictures. I chose to fit the events of “Escape Route” in a single day. Taking the bus to school, going to class, eating lunch with her best friend, going through the motions at work, Alexa’s day rolled in front of my eyes like a short film. I had the sensation of observing the action from the sidelines like a videographer. It was eerie and fun. As a poet, a good day is perhaps a stanza or an incoherent draft, so that for decades I have associated writing with unending guilt. With fiction, 500 to 1000 words rolled out by dinner and I could get up from my desk with a clean sense of having been emptied out. When I got stuck, I went on a walk, took a shower, cooked a meal, and by the next day, another scene had played itself in my mind. I was learning to listen to Alexa and her thoughts, getting to know her as well as learning to tell her story. And I learned again to be grateful for the stories that had been passed onto me to tell.

Phoebe Wang is a writer and educator based in Toronto and a first-generation Chinese-Canadian. Her debut collection of poetry, Admission Requirements (McClelland and Stewart, 2017) was nominated for the Trillium Book Award. Her second collection of poetry, Waking Occupations, is due in Spring 2022. She works as a Writing and Learning Consultant for ELL students at OCAD University. More of her work can be found at www.alittleprint.com.

Header photo courtesy of Jess Bailey