Finding the Form with Tom Wayman

By Tom Wayman

I first met Giorgio, who eventually served as Toronto’s poet laureate between 2004 and 2009, when I went to the University of Windsor to be their writer-in-residence 1975-76. My poetry collection Money and Rain, published by Macmillan of Canada in 1975, had included poems about an eight-month stint working in Burnaby, B.C. as a factory assemblyman for Canadian Kenworth. The UWindsor selection committee felt that my writing about building trucks was a good match for the city, given Windsor’s auto plants integrated with Ford and Chrysler production on both side of the Detroit River.

I can’t remember whether I was introduced to Giorgio through the Italo-Canadian poets then active in Winsor, Mary di Michele and Len Gaspirini, or whether I met him through mutual friends in the Toronto literary scene. I was frequently in Toronto between 1975 and 1996, in part because my parents lived there and in part because during that era Toronto really was the literary centre of the country—different than today, when a proliferation of literary foci across the Dominion has supplanted the former binary paradigm of centre/hinterlands, of national/regional.

However we met, Giorgio and I became friends. I admired not only his poetry, but also his determination not to be Peter George—something new in Canada at that time, when immigrants traditionally Anglicized at least their first names.

In the 1970s, as a result of post-World War II immigration, the population of Toronto had become about one-quarter Italian or of Italian descent—a transformative change for a place known previously for Anglican and Presbyterian rectitude: Toronto the Good. And Giorgio played a vital role in achieving importance in Canadian Literature for the writers in English active among the relative newcomers. In 1978 he put together the first anthology of Italo-Canadian poets writing in English that I was aware of, Roman Candles.

Unlike the current advocates for writing by various racial and sexual micro-minorities, Giorgio in presenting his seventeen authors had confidence in the accomplishment of the poems. He needed neither to attack mainstream CanLit (literary production seen as a zero-sum activity) nor blather about “underrepresentation” (which author can say with a straight face that she or he truly represents his or her community?). Instead, Giorgio states in his Preface, concerning the material he had collected:

The Italo-Canadian experience expressed by these contributors . . . ranges from poems that directly speak from a displaced sensibility to poems that are not conscious of any such dilemma. . . . As poems should be, they are not so much a resolve as they are a discovery. They map out a journey towards a new citizenship, one that has little to do with anti-Americanism or the convenience of a melting-pot.

As a person, Giorgio was easy to feel affection toward. He had a huge heart toward his friends, and a deep seriousness about life, literature, and ideas. His solemn approach regarding the latter sometimes verged on the ridiculous, although he took the ribbing he received for such behavior with an unfailing sense of humor. Good talk and Italian coffee—long before the flooding of North America by corporate espresso—were two things he enjoyed, based on his thoroughgoing appreciation of the sensuous and his delight in people.

The elegy in TNQ was not the first poem I wrote for him. In my 1986 collection, The Face of Jack Munro, published by Harbour, I have a poem called “December Letter to Pier Giorgio Di Cicco in Toronto.” In it I suggest that, since he and I both have large Mediterranean noses, we should decamp to the sub-tropical sun of southern California where

in the end

we will marry women

who never head of Canada, and have children

who never heard of snow.

Instead of taking my advice, Giorgio was ordained a Roman Catholic priest in 1993. He wrote stunning poems about the tougher aspects of that occupation—how to act honestly in conducting a funeral for a family that in a tragic accident has lost their children. And as Toronto poet laureate and afterwards he thought hard and wrote passionately and insightfully about the purpose of a city (I skim the surface of some of his ideas in my elegy).

His sudden death a few days before Christmas in 2019 was a shock to me. I was used to middle-of-the-night phone messages from him where I live in B.C.—being a priest never, as far as I could see, changed Giorgio’s proclivity toward rising around noon and going to bed in the early morning. Plus I’m not sure he ever grasped the concept of time zones. But every message he left me ended with an earnest, “God bless you, Tom. God bless you”. Vintage Giorgio: wishing the best for a friend, even though he knew I’m about as religious as a compressed air impact wrench.

When I wanted to write an elegy for him, tone was all-important. I wanted to capture his mix of self-confidence, engagement with ideas, respect and regard for others, and a refusal to be cowed by precedent or authority (he had various run-ins with the ecclesiastical hierarchy, but stood his ground: “The bishop knows,” he confided in me once, “it’ll be a long time until Toronto has another Catholic priest as poet laureate”). One model for me was the elegy by American spoken word poet Vachel Lindsay (1879-1931) for the founder of the Salvation Army. Lindsay’s poem expresses appreciation of William Booth’s sincere if somewhat simplistic Christian faith, and of his accomplishment in founding a popular new religious movement, while gently mocking the silliness of trying to militarize a religion supposedly based on love.

I knew my poem had to be conversational in structure, given how important conversation was to Giorgio. A rigid stanzaic structure was out, because Giorgio was nothing if not iconoclastic, with a somewhat non-conformist lifestyle even as a priest. And I knew any Heaven for Giorgio would have to offer excellent coffee. Plus, given the Church’s present difficulties with past behavior by some of its representatives, I couldn’t see God‘s Son showing up, as in Lindsay’s elegy, to welcome even the most accomplished ministers—like Giorgio—before they could be properly vetted. Head Office would instead send a functionary, I reasoned. And given the traditional narrow-mindedness of functionaries compared to Giorgio’s broad range of interest in human beings and their communities, I had the plot of the poem.

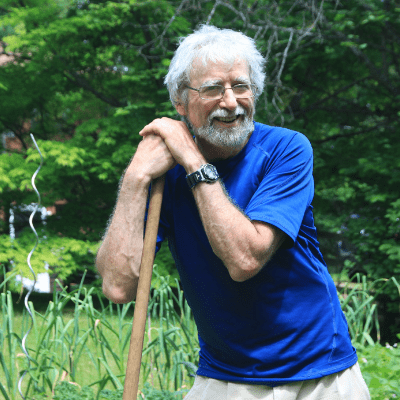

Tom Wayman was named in 2015 a Vancouver Literary Landmark, with a plaque on the city’s Commercial Dr. commemorating his championing of people writing for themselves about their employment. His most recent collections of poems include Helpless Angels (Thistledown, 2017), shortlisted for the 2020 Western Canada Jewish Book Awards, and Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time (Harbour, 2020), which appeared just before the pandemic lockdown, despite the book’s subtitle. In December 2020, North Vancouver’s Alfred Gustav Press published a chapbook of his, The House Dreaming in the Snow. He lives in the Selkirk Mountains of southeastern B.C.

Photos courtesy of Daniele Levis Pelusi