Finding the Form with Susan Glickman

By Susan Glickman

In March of 2008, I saw the National Ballet of Canada perform Marie Chouinard’s brilliant choreography to Chopin’s 24 Preludes, Opus 28 – one of my favourite pieces of piano music. One might expect a ballet company to give a very Romantic interpretation to anything by Chopin, with muscular men in tights lifting exquisite women in tutus who faint into their arms after prolonged flirtation and much fluttering of arms and legs. But this version was unexpected – fierce, modern, athletic and angular – counterpointing the music in ways that made one listen to it afresh, bringing out Chopin’s sharp edges, unexpected dissonances, and rhythm changes. It made me remember why I love the preludes so much: because of their undertow of mysterious emotion and the way moving from one to the next, around the circle of fifths, not only illuminates the sonic possibilities of each key but also tells you something, however cryptic, about the composer’s personal life.

Shortly thereafter I decided to see if I could “translate” the music into poetry in the same way Chouinard had translated it into movement. This project was justified not only by the success of Chouinard’s choreography but also by what Julia Kristeva says about intertextuality:

The concept of Kristevian intertextuality enables an understanding of how “conventional” poetic devices, such as meter and structure, can indeed be worked by the poet in ways that allow us to partake in the struggle of being in language. Kristeva laments that intertextuality “has often been understood in the banal sense of ‘study of sources’” when in fact, “intertextuality denotes [a] transposition of one (or several) sign-system(s) into another” (KR, 111). A sign system, such as music, can be transfused into another system, such as language, in order to achieve new registers of experience (KR, 93). In Kristevian terms, the rhythm is what guarantees that the words will be more or other than the symbolic/denotative allows.

-Julia Kristeva, “Revolution in Poetic Language,” The Kristeva Reader, ed. Toril Moi (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986).

What this project involved was:

1) Doing a lot of research about the 24 Preludes’ musical structure and the history of their composition.

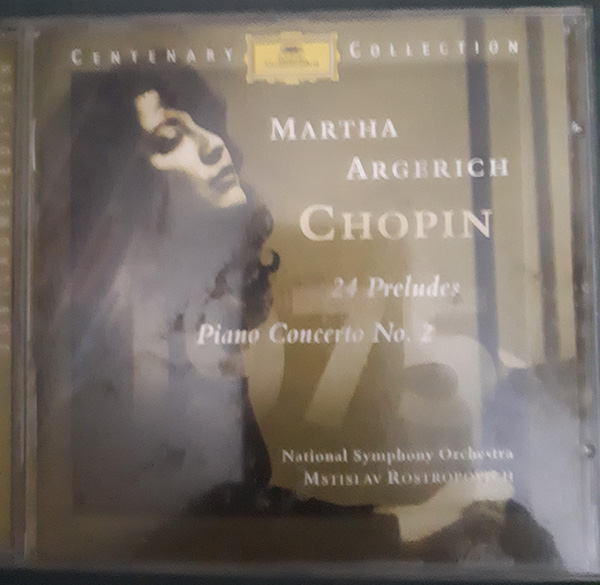

2) Listening obsessively to Martha Argerich’s fantastic recording of the preludes on Deutsche Grammophon, and scribbling personal associations evoked during the listening process, many of which turned out to relate to travel and the negotiation of my place in the world.

Over several years, I wrote poems inspired by all twenty-four of the preludes. Initially they were governed quite strictly by their original form. First, I made an arbitrary rule that one page of text = one minute of Argerich’s (admittedly unusually fast) playing time. More importantly, I let the music govern line-length and stanza form as much as possible. I wrote the pieces while listening to the music, stopping and replaying it obsessively as though I were writing lyrics to a song – which my son, a professional musician, does all the time. I suspect I drove my family crazy the way he does, working towards the best version of each composition in his studio upstairs.

During that same period, I was writing fiction for both adults and children, working as a freelance editor, nursing invalids, and teaching creative writing at Ryerson and U of T, so my immersion in Chopin was not as uninterrupted as I would have liked. Chopin himself wrote the preludes during an intense burst of activity over a two-year period: mostly over a single winter in a drafty chalet where he was holed up with Georges Sand.

I often wonder what it would be like to have that kind of intense writing time and to have a patron who believed in my work enough to give it to me. But perhaps such rhapsodic attention isn’t my style. I have always gone back and forth between different projects and am not good at shutting out the world to concentrate exclusively on my art (even saying “my art” makes me embarrassed. It just seems too pretentious).

Eventually I realized that twenty-four poems, most of which were only a single page long, would not fill a book, so I started writing other kinds of poems as well as revisiting older work. Some of these pieces proved to be better than some of the Chopin exercises and ultimately, only fourteen of the “preludes” made it into the book published last year as What We Carry, scattered throughout to give it coherence rather than clumped together as a discrete section. Over the ten years I was working on my “preludes” they evolved from being fairly close transcriptions of the music to becoming more and more independent of their original inspiration – to becoming themselves as poetry. Still, I have always hoped that somebody, somewhere, some day, might decide to listen to Chopin’s 24 Preludes – maybe even to the Argerich interpretations — while reading them.

Susan Glickman lives, writes, paints, and gardens in Toronto where she works as a freelance editor. She is the author of seven volumes of poetry, most recently What We Carry (April, 2019). Her first novel, The Violin Lover (Goose Lane, 2006) won the Canadian Jewish Book Award for fiction and was named one of the year’s best novels by The National Post. Her second, The Tale-

Teller (Cormorant, 2012), was a best-seller in Quebec after appearing in French as Les Aventures étranges et surprenantes Esther Brandeau, moussaillon (Editions du Boréal: 2013).Safe as Houses was published in 2015, and The Discovery of Flight in 2018.

Photos by Susan Glickman and Toan Klein. Header by Spencer Imbrock on Unsplash.