That Hair-Flipping Moment of Truth: On my Relationship with The New Quarterly

I remember the precise moment when I decided that I would be a writer when I grew up. I was still in high school, and I was standing outside my bedroom door in my family’s crowded house, waiting in line for the bathroom (in addition to having five children, my parents frequently hosted international students, and that year a German teenager was living with us too). There was no particular reason to be thinking about writing at that precise moment, but in my memory, I stood on the wood boards outside the closed bathroom door, flipped my head upside down, ran my fingers through my hair, and decided, I’m going to be a writer. I flipped my head back up, the bathroom door opened, I went in and stood for a moment looking at myself in the mirror. I’m going to be a writer. My next thought was: how? But the how seemed to expand instantly in an almost mystical way, my mind filled not with a romantic jaunt down a magical path, but with a grittier set of facts and possibilities—I would set my course, now, with a rigorous, even boring or humble plan: to read, read, read and to write, write, write.

I would get a degree in English literature, for starters.

And I would try to get published.

Strangely, and perhaps against the odds, my plan, conceived in a narcissistic teenage moment, gazing into my own eyes in the mirror with excitement and intense purpose, actually worked.

Now, I am in the position to mentor students who share those same ambitions, whose writing lives are freshly beginning, and who come to me asking: how? How can I become a writer? What steps can I take? What plan can I follow? How is this done?

There are many ways to answer this question, of course, but the most honest answer is both simple and excruciating. That’s because the simplest and most excruciating news is that if you are a writer, you will write, and nothing will stop you from doing so, including endless rejection, and including any advice I could possibly offer.

This is not the news most students want to hear. Because they aren’t really asking, how can I be a writer, but rather, how can I be a famous writer, which begins with the more basic problem of how can I get published?

Here is where The New Quarterly comes in.

Once I’ve delivered the news that a writer is someone who writes no matter the outcome, I tell them about my own writing path, and I always begin with The New Quarterly, because The New Quarterly is where I began, as a published writer.

Although this isn’t decisively linked in my memory, it’s quite possible that my hair-flipping moment of truth was related to an extraordinary event that happened in my final year of high school: I submitted poems to The New Quarterly, on the advice of my English teacher, and two of my poems were accepted. This was actually a hugely instructive experience for me, because it taught me about the pace of time in publishing. The sooner an aspiring writer can come to peace with the pace of time in publishing, the happier that writer will be.

I wrote the poems when I was 16.

The poems were accepted when I was 17.

They were published just after I’d turned 19.

When I tell students this, their jaws drop.

Of course, a person can publish her poems online as she wishes now, and there are writers who have succeeded magnificently outside of the traditional publishing model, but I can’t speak to that.

All I can speak to is the slow pace of traditional publishing—which, in my experience, is a pace that serves the writing, if perhaps not the writer, or at least not the writer’s ego, nor the writer’s bank account.

Instant success? I have no advice on that front. Aspiring writers and published writers alike almost always need a day job or a supportive partner—and no, grants and prizes are not the answer, in the same way that lottery tickets are not a solution to poverty. This is a problem, a very serious problem, but it’s not one I’ve figured out how to solve.

I can only speak to the slow pace of development, as a writer, the need for time, for patience, for encouragement along the way, for hope.

It was winter, 1994: I remember looking at my first published poems, printed on clean white pages in The New Quarterly—my words!—and I remember thinking: I have arrived. I am a writer! This is it! All other evidence was against me: broke, working part-time and going to school part-time, I’d recently moved back into my parents’ house, and was sleeping in a provisional space, in the front room on the main floor, where a streetlight shone through the window all night, in a house packed full of international students and siblings.

Where exactly had I arrived?

It is easy to mock my exuberance as naïve. But I was also right, in a way. I had arrived at a milestone. Here, I could stick a marker in the ground: I was a published writer.

Do you realize, do you understand, do you appreciate what you are doing when you publish a young writer, a new writer, a new voice? You are giving this person fuel for the fire—in the form of hope.

I don’t say this lightly.

I wouldn’t publish again for several years, despite sending out numerous stories and poems. My work would be rejected far more times that it would be accepted—sometimes with a kind note accompanying the rejection, and sometimes with the dreaded form letter—I came to recognize the fat envelope in the mail with my own handwriting on the front. Disappointment was crushing and immediate, and mercifully temporary. Somehow, I understood that while I wasn’t the writer I wanted to be, yet, each rejection wasn’t the end. I just had more to learn, more work to do.

The New Quarterly sent me its fair share of rejection letters. I’m afraid I did not keep them. I had and still have a habit of throwing rejection letters in the recycling bin. Maybe it’s cowardly, but a person in this business needs her coping mechanisms.

Now, to list the ways in which The New Quarterly has been a companion and friend throughout my writing life.

As I’ve said, the magazine was the first to publish my work: two poems. A few years later, it published several more poems; by now, I was in grad school, longing to be a writer rather than an academic, and the acceptance letter gave me reason to dream.

I’m sad to report that the magazine rejected at least one story that would later be published in my first book, Hair Hat. In fact, I didn’t follow the classic trajectory of the aspiring Canadian writer—I was rejected roundly by all the Canadian literary magazines, yet landed a major Canadian publisher for my first collection of stories, giving me the impression that it was easier to get published in book form than in magazines.

After that book, however, it was easier to get published in The New Quarterly.

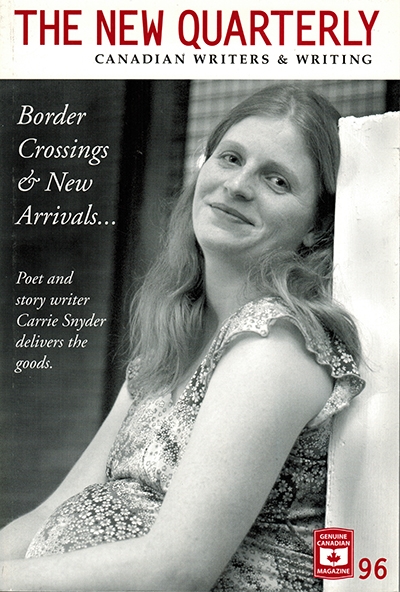

In 2005, I was featured as the cover girl, massively pregnant with my third child, an issue that also featured a story, several poems, and an interview with the magnificent Charlene Diehl, who had been one of my profs in university.

In 2005, I was featured as the cover girl, massively pregnant with my third child, an issue that also featured a story, several poems, and an interview with the magnificent Charlene Diehl, who had been one of my profs in university.

Several years later, when I was struggling to find the shape for my second book, having spent years trying to write it as a novel, The New Quarterly stepped in with Ontario Arts Council funding and, just as importantly, encouragement—then-editor Kim Jernigan wrote to tell me that she thought I was on the right path with these semi-autobiographical stories.

These stories, of course, grew up to be The Juliet Stories, a finalist for the Governor-General’s Award for fiction in 2012, at which point, I told myself, again, Now, I have arrived. Had I won, I might have quit then and there, having reached the pinnacle of what I had imagined for myself as a writer, when I was a teenager flipping her hair outside the bathroom in her parents’ house.

TNQ—as it’s now called—has also published my creative non-fiction, helping me become a finalist for a National Magazine Award.

Finally, as my career progressed, the magazine invited me to become a mentor, bringing me on as a judge, starting in 2013, for the Peter Hinchcliffe Fiction Contest (Peter Hinchcliffe was one of my profs in university, and possibly the kindest person I’ve ever met), and in 2017, inviting me to be a consulting editor, with a focus on young writers. I’ve also been involved with the Wild Writers Festival since its inception in 2012, as a panelist, moderator, and workshop facilitator, and (I like to think) informal host, welcoming writers from across Canada to Waterloo.

Every term, TNQ’s editor Pamela Mulloy comes into my creative writing class at the University of Waterloo and talks to the students about the importance of getting their work out into the world, developing relationships with editors, and learning from rejection. Last winter, I was thrilled to come full circle—one of my students published her first story in TNQ, a story she’d written in my class, and that I’d helped her edit and submit. Sometimes I suspect that this was the arrival I’d been anticipating my whole writing life—it was in some powerful and unexpected way, the proudest moment of my career.

What I want to say is this: by making room for new voices, by nurturing those of us who are further along in our careers, but who still need encouragement—in all of this I see another word I associate with TNQ, a word every writer needs: COURAGE.

Courage is what TNQ has given me, all along.

Courage is what I try to give to my students.

Courage is what we can all give to each other too, as we continue to wrestle with change, to look beyond ourselves, to listen and learn, to challenge the status quo, and to publish excellent writing.

Bio: Carrie Snyder lives in Waterloo, Ontario with her family. She teaches creative writing at the University of Waterloo, and is the author of three books of fiction for adults, and two books for children, most recently, Jammie Day! She blogs at www.carriesnyder.com.