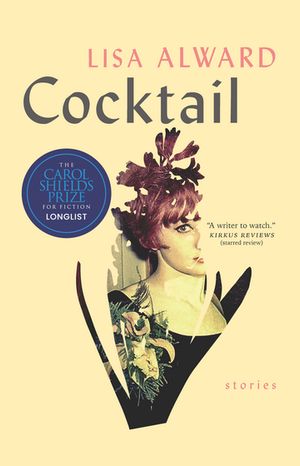

Launched: Cocktail by Lisa Alward

By Laura Rock Gaughan

Lisa Alward’s first book, Cocktail, was published by Biblioasis last fall. Alward’s stories have won The Fiddlehead Prize and the Peter Hinchcliffe Short Fiction Award and have appeared in Best Canadian Stories as well as The Journey Prize Stories. She grew up in Halifax and worked for several years in literary publishing in Toronto before moving with her young family to Vancouver and ultimately to Fredericton, where she lives with her husband, John.

Q: First, let’s talk about the very positive critical reception that Cocktail has received since it was released. And it was longlisted for the Carol Shields Prize and is a finalist for a New Brunswick Book Award. Congratulations! As a debut author, and as the author of a book of short stories, what were your expectations going in? How have you processed this good news?

Well, I was not expecting to be on the Carol Shields long list. Right after I heard, I had to update my bio and compose a quote for the prize foundation and struggled all morning trying to come up with any words at all. Later, after I’d had a chance to process the announcement more, I felt deeply honoured and still do, in no small part because Carol Shields is one of my fiction muses. (Swann was my favourite novel in my 20s and ditto The Stone Diaries in my 30s. And her writing journey has always inspired me: how for years she could only write in the hour and a bit before her five children came home for lunch and how she didn’t publish her first novel until 40.)

As for my expectations going in, I’m conscious of having kept these deliberately, almost forcibly, low. This has had as much to do with self-protection as with any rational assessment of the prospects for a first collection of stories. I haven’t wanted to feel disappointed, to let that mar the pleasure of having a book out in the world after so many years of believing this would never happen. During production, I remember telling myself that all that matters is creating a beautiful object I can share with family and friends. That I got this, as well as so many thoughtful reviews and two prize nominations, still feels like a dream.

Q: The stories in Cocktail are varied in their settings and conflicts but connected by theme—women in relationships, navigating their own desires versus what is expected of them, whether that’s by their husbands, children, parents, other mothers, or society. Your characters look askance at the conditions of their life, quietly appalled. They’re digging into the past, exposing sedimentary layers, often with wry observations.

What is it about the changing conditions of women’s lives that fascinates you, artistically? Is it the small details, or politics of the day, or something else that is a springboard into story for you?

For me, the springboard is almost always an image. Often this is more of a fragment, the picture in my mind not at all clear at first. Occasionally, as in my title story, it’s just a piece of remembered speech. The problem with parties is people don’t drink enough. My mother really did say this once, and I laughed, just like my narrator in the story. Yet, however vague it may be, there are feelings attached to this image, feelings that interest me, that I don’t fully understand, that keep pricking at me, and in a sense the story becomes an exploration of all that. This, I guess, is my round-about way of saying that I don’t tend to think in terms of theme and certainly not politics, certainly not at the outset. I’m too preoccupied with uncovering the story. I love Stephen King’s metaphor of stories as fossils, or relics, “part of an undiscovered pre-existing world,” and the writer’s challenge being getting as much of one out of the ground as possible. It does feel as though I’m excavating.

Later on, I can see themes in my work. All those quietly appalled women you mention, like Laura in “Hyacinth Girl” and Ruth in “Bundle of Joy,” wondering how they let themselves get so stuck. And safety — what lengths we’ll go to stay safe and yet the risks we’re also prepared to take to get what we want. Doubt, I think, is another theme. Deborah in “Little Girl Lost,” for instance, has left her children for a lover but finds herself worrying over his endearments, clinking her memories of these together like beads on a rosary. And then there are all the repeating images: the messy houses and failed artist figures, the natural environments that seem alien or frightening, all those stubbed cigarettes and half-empty glasses. But this recognition seems to come from a long way off in my brain. Filling out marketing forms definitely helped! So have reviews. I feel I’ve learned so much from other readers.

Q: Doubt is a rich vein. That reminds me of Gwyneth’s (justifiable!) doubt about her ex-partner Ray’s plans to finish a tumbledown cottage and cultivate an organic garden in “Old Growth,” a story I have loved since it first appeared in The New Quarterly.

According to your bio, you began writing fiction at the age of 50. Your book came out when you were 61, which I only know because you mentioned it in an interview or perhaps a social media post. It struck me at the time: you owned this fact with pride, and I wanted to ask you about your perceptions of our writing culture with respect to age. The notion that an emerging writer is often synonymous with young writer. That pressure on writers to produce quickly—and yet, we have many examples of first books published successfully after 50. Did it worry you, before you pulled together your manuscript?

While you could argue that Carol Shields didn’t really start that late, I’m definitely a late bloomer. Although I wrote throughout my childhood and teenaged years, I had pretty much stopped by the end of university. For a long time, almost three decades long, I accepted what seemed so painfully obvious to me at 22: that I simply wasn’t cut out to be a writer, that I lacked not only talent but the necessary stamina and grit. Looking back now, though, I can see that U of T in the early 80s was not a particularly nurturing environment for a young aspiring female writer from the Maritimes with low-ish self-confidence. For one, there was the problem of the courses required for my English specialist, which were still astonishingly male-centric in those days. I did take a fourth-year seminar from one of the few female professors in the department (who introduced me to Virginia Woolf), but as penance I had to put up with a male classmate constantly challenging her literary authority. Outside the ivory tower, women were writing, but inside it felt as if only the guys counted. I remember chatting with another aspiring fiction writer at a house party. He was Irish with the beard and slight stoop of a young Joyce. “I want to write too,” I confessed over my draft beer, and I could tell he thought that he was letting me down gently when he mused, “Well, there aren’t a lot of important woman writers.” And the worst part? The only rebuttal I could think of was the Brontës.

Fear of failure was no doubt also a factor. I didn’t know in my 20s that writing is mired in failure, that this is one fear you never get over. At any rate, after my MA, I gave up the idea of trying to write and looked around for a writing-adjacent job in publishing and then — as in To the Lighthouse — time passed. When I finally dared to try fiction again at 50, it took me eight years to compile enough good stories for a book. That book came out last September when, as you note, I was 61. I’m not sure I’d go far as to say I own the fact of my age, but it is a fact, and I try not to be embarrassed or discomforted by it. And while we do associate emerging writers with youth, there’s thankfully no cut-off age for starting to write. This is the literary world after all, not Hollywood. Not tennis! However, I am a slow writer, or I have been up to now. I write usually four or five drafts of a story and then tinker, tinker, tinker. I would certainly like to write my next book a little faster, not so much because of that pressure to perform, which I agree is out there, as the sense that I might not have much time left.

Q: As someone who worked in literary publishing long ago, you likely had more insight than most into the processes involved in bringing a Canadian literary title to market. But it’s different being the author, of course. What surprised you about the publishing process, and the launching of your book into the world?

I worked in publishing from 1985 to 1994, first as a publicist for Dundurn Press, then as a rep with the sales agency Cariad, then as sales manager for the Literary Press Group, and, after my daughter was born, as a freelance publicist and marketing consultant. Once my husband and I moved to Fredericton, I continued to freelance, including doing some proofreading and copy editing. If I learned anything valuable about being an author from these experiences, it’s humility. There’s nothing like spending your days pitching poetry and fiction by first-time authors to tired booksellers or leaving yet another phone message with the producer of Morningside to make you appreciative of how hard it is to get a book noticed, especially one from an independent (i.e., Canadian-owned) publisher, and I feel so grateful to Biblioasis for all their incredible work on Cocktail’s behalf.

If anything has surprised me, it’s how insulated I am as an author from publishing’s front lines. Apart from filling out those marketing forms and giving my thoughts on cover design and, of course, showing up for things, I’ve had very little do with sales and marketing. No complaints, by the way! Another surprise is the whole community aspect. I’m now in touch with writers across the country and have heard from so many old friends as well as strangers who’ve read and enjoyed my book. This has been a tremendous source of joy.

Q: What are you working on now?

I’m just starting work on a new collection. The story that I think could become the title story is inspired by a family drama from my childhood. After my grandfather died, my grandmother made a rash and disastrous second marriage to a handyman who’d lived for years two doors down from her in the same village on Nova Scotia’s south shore. This was in 1967, the Summer of Love, and gifts of flowers were involved. Four years later, my mother and her sister “kidnapped” her. How they came to this decision and what actually happened that morning has always intrigued me, and I’m excited to see what else I might discover.

Laura Rock Gaughan is the author of Motherish, a short story collection. Her fiction and essays have appeared in Canadian, Irish, and US journals.