One in the Bow and One in the Stern: Robert Reid and Wesley W. Bates on Casting Their Collaboration

By Robert Reid and Wesley W. Bates

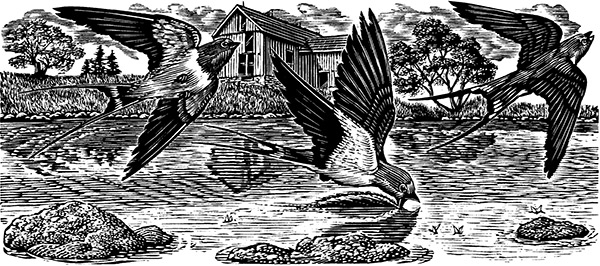

Robert Reid is a writer whose career in journalism spanned forty years. Wesley W. Bates is one of Canada’s best-known wood engravers (whose work appeared on the cover of The New Quarterly’s Issue 138). Both are avid fly fishers. Casting into Mystery, published by The Porcupine’s Quill in February 2020, tackles their love of angling through creative collaboration. The book features a combination of text and image and provides a glimpse inside a sporting culture teeming with literature, art, and music. Discover more or purchase a copy from your local bookshop!

Robert Reid: Wes, we owe so much to fly fishing. It served as the foundation of our creative partnership, not to mention our friendship. When we met for the first time after many years, you asked whether I would be interested in working together on a book. Shortly after I began posting essays about fly fishing on the blog I started after retiring, I contemplated working with you on such a project. We were reading from the same page without knowing we shared a common book.

Wesley W. Bates: Yes, it is a delightful fusion of our separate loves of angling and rivers that made this book happen. Before you and I met, I had tested the water with a couple of writers about doing something involving fishing. Back then, I was in the “romantic” grip of fly fishing and I suppose my aims were different from those of the authors I had approached. As I recall when we met, we chatted briefly about fly fishing because I had an engraving of the subject in the exhibition you reviewed. I’m sure that’s where the spark of our book was ignited, at least for me. Later, when I was introduced to your blog where you write so elegantly about fly angling, the hook was set. All that remained was finding an opportunity to pitch you the idea.

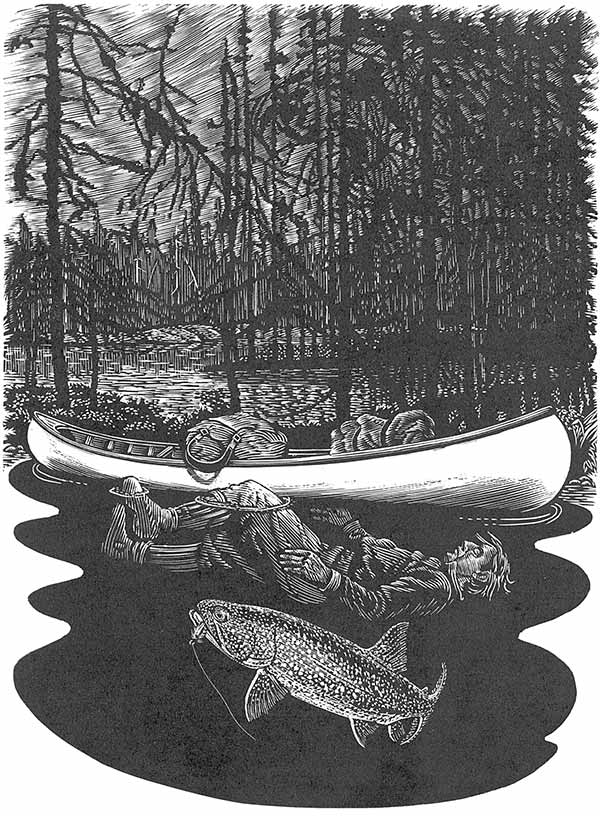

RR: Our goal for the book from the beginning was to blend word and image. Your engravings would be a visual narrative running parallel to my textual narrative. Our creative partnership would be like two fly anglers in a canoe, one in the bow and one in the stern, both paddling in the same direction but casting from opposite sides when fishing.

WB: Funny that you mention two anglers in a canoe. You triggered my memory of fishing with my father in the mountain lakes of central British Columbia. There are hundreds of small lakes that are stocked with Kamloops trout. Dad and I would paddle the canoe around a lake following the sun progress, as did the fish. We used fly rods, but we trolled with spinners and we were usually successful. Your image of two fly anglers casting off the opposite sides of the canoe does fit our approach very well.

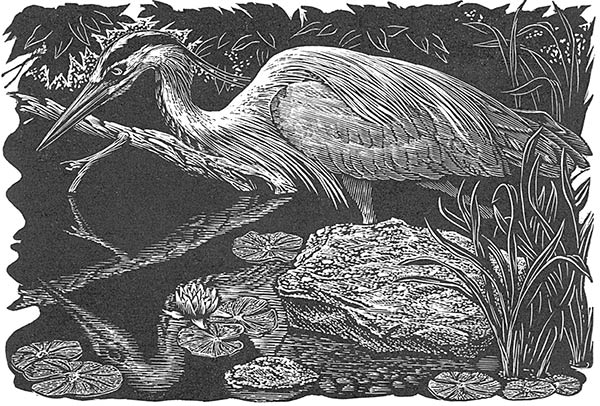

RR: We were “casting from opposite sides” in the book, but there were some instances of crossover between text and image. Like when I refer to Tom Thomson as an artist with fins, and your portrait has him submerged in a lake along with a trout. Or when I talk about fly fishing as a threshold experience and you portray a great blue heron next to his mirror image on the surface of water. For me, these are examples of creative synchronicity.

“I like to think our book resembles the two-headed trout. You know the (fish)tale. A native brook trout makes his way to the Junction Pool where the Willowemoc meets the Beaverkill. Both rivers are so beautiful the trout can’t decide which one to navigate, so he grows two heads.”

WB: Your approach to the subject of Tom Thomson is refreshing and insightful. When I heard you give a talk about your understanding of Thomson as a fly fisherman, you opened a new perspective. I still see him as a major artist. And the mystery of his death retains a sense of intrigue. But now when I consider his work, I see deeper into his relationship with subject matter and his connection to nature through angling.

RR: I like to think our book resembles the two-headed trout. You know the (fish)tale. A native brook trout makes his way to the Junction Pool where the Willowemoc meets the Beaverkill. Both rivers are so beautiful the trout can’t decide which one to navigate, so he grows two heads. I think of our book as embodying that legendary trout.

WB: It’s no secret my main interest is creating images, so I wanted our collaboration to blend two perspectives: one literary, the other pictorial. The medium I work in is wood engraving, which had its golden age in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Wood engraving dominated the book world as the preferred method of transferring an image onto paper. As you enjoy pointing out, that same period is acknowledged as the golden age of fly fishing. During the Victorian period, fly fishing was considered a form of art. The artificial flies created then were akin to pieces of jewelry rather than mere imitations of insects or bait fish. There are books filled with beautiful wood-engraved illustrations of angling scenes, gear, and fish as well as marvelously tied flies.

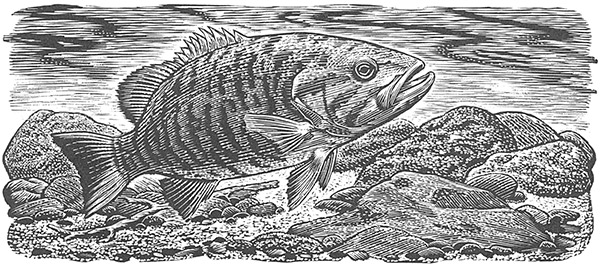

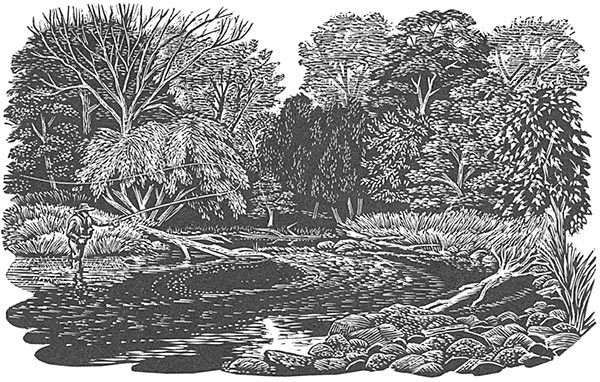

For me, the combination of type and wood engravings is a “hatch” made in book heaven. I wanted my engravings to convey a strong feeling of place by bringing the reader in intimate contact with the riverbank, an insect on a leaf, a trout in the water.

RR: Casting into Mystery began as a series of straightforward accounts of angling outings. My aim was accuracy. But as the personal accounts transformed into chapters for a book, I began hearing the voices of literary authors and angling writers, past and present. I heard the melodies of composers and the lyrics of songwriters, which were joined by the images of filmmakers and visual artists. I was no longer a fly angler who writes, but a writer who fly fishes. It was a creative transformation, a shift from accuracy to truth.

I consider my narrative as accessible to fly anglers and non-anglers alike. Like your efforts to convey a strong feeling of place to the reader, I want readers to pretend they are traversing a wide riffle to get to a pool on the other side of a river that holds big fish. The only way of getting across safely, and remain relatively dry, is to jump from boulder to boulder—Brad Pitt in A River Runs Through It. All the writers, artists and musicians to whom I refer are boulders that punctuate my prose narrative.

WB: I like how you put it: “I was no longer a fly angler who writes, but a writer who fly fishes.” If I may cast an identical line: I’m an artist who fly fishes. For me, the transformation happened as I studied the work of two artists in particular. The Englishman Thomas Bewick and the American Winslow Homer. Bewick is credited with developing wood engraving in the late eighteenth century. He was an avid fisherman in the rivers and streams of Northumberland, near Newcastle upon Tyne. He engraved many angling scenes. The more I learned about fly angling, the more I appreciated Bewick’s work, not to mention his way of seeing. In the miniature space wood engraving allows, Bewick was able to depict landscape and personality in his figures.

Homer’s territory for the greater part of his artistic life—which included fly fishing—was the northeast United States, especially the rugged seashores of Maine and the wilds of the Adirondacks. His painting—in particular his watercolours—of fishing and hunting subjects are impressive for their lack of romanticism or heroism. The plainness, frankness, and truth of his visual narratives set him apart from his peers.

Both Bewick and Homer demonstrated how light illuminates our world. Bewick worked in a medium in which every stroke of the graver adds light to the image. Homer illumined with colour. Both artists had deep love and knowledge of their subjects.

RR: I’m fascinated by the connection between fly angling literature and the importance of place. Fly anglers cherish the home waters that shape their identity; likewise, writers define themselves, in part, by giving expression to place through their craft.

WB: I feel you evoke place very well in your writing. One has to be part of a place, and that requires long association. Before I moved to where I live now in Clifford, I visited the area to fish. It was twelve years before I left the city to set down roots in a rural community. Becoming part of a place is difficult if you don’t interact with your immediate environment. Fishing has been significant to my understanding of where I live. Standing in a river is an intimate act of relationship with the wider landscape, the flora and fauna and network of human relationships Water is the centrepiece of any community. My work as an artist developed through my interaction with riverscape—it’s a bonus that I can also go fishing.

RR: While the turn of the last century is recognized as the golden age of fly fishing, I contend that we are now living in the golden age of fly fishing literature. Incidentally, Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler, first published in 1653, is the most frequently reprinted English-language book of all time, save for the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress. But it is only recently that fly angling writing has turned away from the hows of catching fish to the whys of fishing. Even though it is an apprenticeship memoir, a reader gains precious little instruction on how to catch fish from Casting into Mystery. It’s not an instructional manual by any stretch. Catching fish is incidental. Instead, it explores what is gained from fishing with fur and feather.

WB: You are so right. Thanks to social media, instruction on how to catch fish has been taken away from writers and artists. That allows us to engage our imaginations in other matters and with other concerns related to the “art” of fly fishing.

RR: With that in mind, I hope readers view our book beyond the confines of sporting literature. I have long been interested in what is sometimes referred as the Rural Tradition. The British writer Robert Macfarlane is a contemporary with whom I share a common literary goal. I try to do for fly fishing what he has does so brilliantly with walking and hiking.

Similarly, I see our book as crossing over into nature writing. While we might think of nature writing as exploring wild and remote places, devoid of human contact, the nature writing on which our book is based reflects Thoreau, Annie Dillard or Wendell Berry more than John Muir, Rick Bass or Barry Lopez in the High Arctic.

WB: The Rural Tradition interests me as well. In the engraving world, there are some great English artists, such as Thomas Bewick (already mentioned), Howard Phipps, and Monica Poole. The English have a long and rich tradition of wood engravers working with rural themes and settings. In America, there is Clare Leighton, an import from England, and Thomas W. Nason, known as the poet engraver of New England. These are the engravers who have most inspired me. Wood engraving is a slow and deliberate process. The time for observation and searching for detail is important, but for me it’s really about finding the light. I look for a balance between accurate detail and personal stylization, the proper anatomical gesture to complement the graphic strength in the subject. In our book, I’m not illustrating your words as much as adding a complimentary visual narrative of place.

To my way of thinking, the Rural Tradition is a weaving together of the natural landscape and the cultivated landscape. The narrative lies in the intersection of these two landscapes. A riverscape is a wonderful expression of the natural world; with a fly angler included, the wild and the cultivated take on the beauty of passion and devotion.

RR: Regardless of the tradition, though, the first thing a reader should do when they consider our book is interpret its title literally as well as metaphorically. Essentially, our book is an investigation into the mysteries of fly angling, which are emblematic of life’s larger mysteries. Fly angling provides the vocabulary, both textual and visual, through which we try to give shape and substance to the mysteries that envelop us. We could spend a lifetime looking for answers to fundamental questions and be thwarted in our search for meaning and purpose. Fly fishing has taught me that it is enough to wade a river, cast a fly, and surrender to the embrace of mystery.

WB: I feel fortunate to be collaborating with you on this project. I have learned more about fly fishing in the last two years hanging out and fishing with you than I did on my own over many years. It goes back to becoming an integral part of a particular place. Drawing and painting while up to my waist in a river is comparable to wading a river with a fly rod in hand. The perspective is the same, even if the intent differs. What I gain in knowing about where I am opens me up to my sense of place. At the same time, what I have yet to see and come to know is even greater. That’s where mystery comes in. It’s the kind of mystery that is a part of being there.

RR: One of the things that delights me most about our book is its subversiveness. On the one hand, we try to persuade non-anglers that fly fishing is not about catching fish. On the other hand, we try to persuade anglers that fly fishing is about more than catching fish. Whatever practical things fly angling offers, it also serves as a path towards healing. It’s not a sport in any conventional sense, like golfing or tennis—or even tossing a hard lure from a bass boat. At its root, fly fishing is an imaginative act, which links it to other forms of art and creativity. It’s no coincidence that so many artists are drawn to fly fishing and, conversely, that fly fishing inspires so much art.

WB: I couldn’t agree more.

Photos courtesy of Wesley Bates.