Tamas Dobozy’s Writing Space

By Tamas Dobozy

It is very important for a writer to work in a public space, where disturbance is continual. With the current plague, e.g. C19, I have taken advantage of collective quarantine to situate my desk at the veritable crossroads of my home.

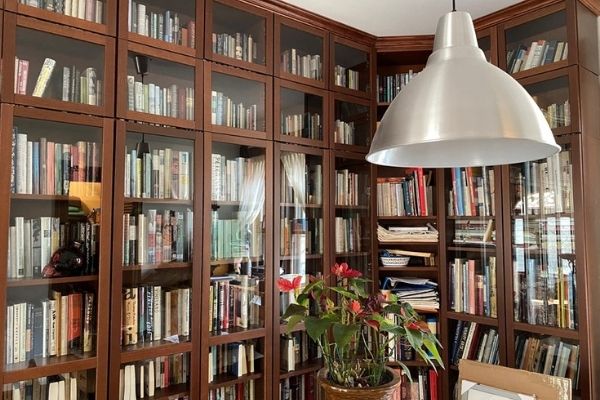

This dining room location also happens, not incidentally, to be the site of my library which allows me simultaneous access, while I am writing, not only to my books and pens, but also dinner.

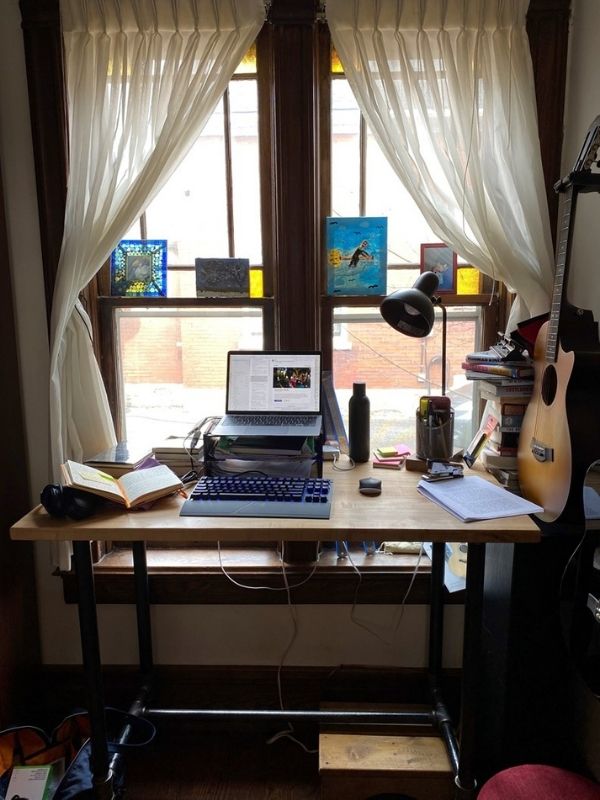

The proximity of my guitar is also critical during extended periods of writing time, because not infrequently I find that playing the C Major Scale, which happens to be my forte on the guitar, further enables that “zoning out” so crucial to entering “the space” where “the magic of writing” takes place. In this particular photograph, I believe I am on the tail end of the “fa” part of the scale.

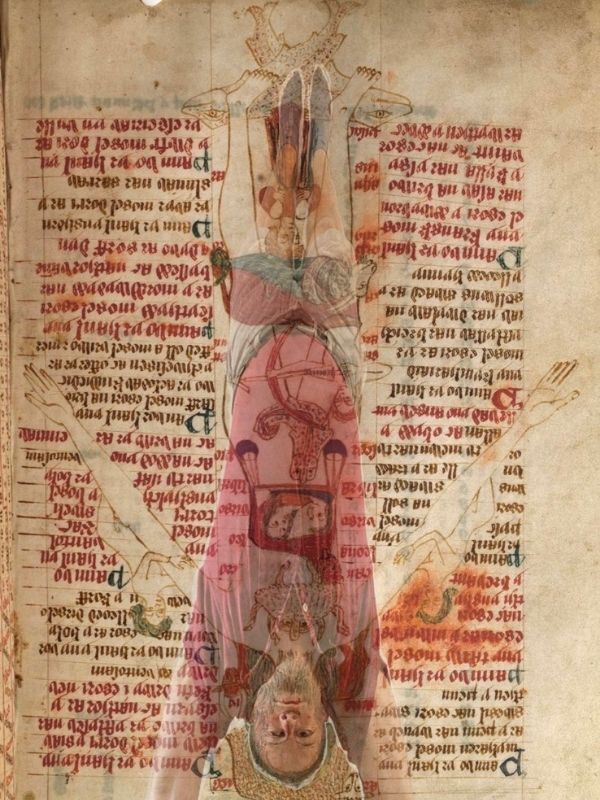

Another thing that helps writing—and this has been known at least since medieval times, if not earlier—is holding oneself upside down for prolonged periods insofar as one’s arms allow it, to increase the flow of blood, and by extension humours, to one’s brain. Two or three seconds is really all you need, which also, luckily, happens to be about all I can manage. This is what we, in the fancy English professor industry, call “embodied knowledge,” where your knowing is directly informed by the sensory information and general disposition of straightforward physical being.

The overlay from Cornelius van Den Kneijnsberg’s infamous treatise, “Quae Tanta Ineptias!” (c. 1183) upon my straining and tense form shows precisely which organs account for the particular emotion (liver = hysteria, gallbladder = schizophrenic delusion, etc.) that informs my writing process, depending, of course, on what any given character needs, at any given moment in the writing, to feel, with slight micro second adjustments in my arms allowing that particular organ to pump slightly more blood into my brain than the others, delivering better “embodied information.” It is therefore, and I guess obviously, important for me to have a wall space close to my writing desk which allows me sufficient support for my weight, since my aesthetics instructor, Coach Nyhof, hasn’t quite been able—and may, now that I think about it, never be able—to train me to support myself in this way without the help of a structure.

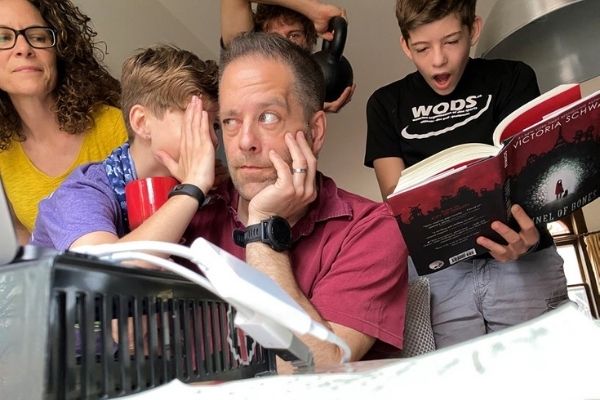

Finally, and most importantly, creating a public workspace like this allows for the smooth interplay of inspiration with interruption, or, if you prefer, “the collaborative process,” in which my family members inspire me to question the plot and character elements I’ve chosen

to focus with determination on certain narrative intentions

or to assert my authorial independence in the face of overwhelming criticism.

I recommend this work environment, and not just a little, to any writer who finds it creatively conducive to work in a place where:

1. Books and dinner are both nearby;

2. One is continuously in the midst of sometimes harmonious, sometimes conflicting, sometimes mutually independent conversations;

3. The apparatuses of creative assistance (pens, guitars, handstands) are readily available; and

4. There is nowhere else to go because of the plague.

Tamas Dobozy’s work has appeared in One Story, Fiction, Agni, and Granta. He has won an O Henry Prize, the Gold Medal for Fiction at the National Magazine Awards, and his book Siege 13: Stories won the 2012 Rogers Writers Trust of Canada Fiction Prize. He teaches at Wilfrid Laurier University.

Photos courtesy of Henry Dobozy.