What is Margaret Watson Reading?

By Margaret Watson

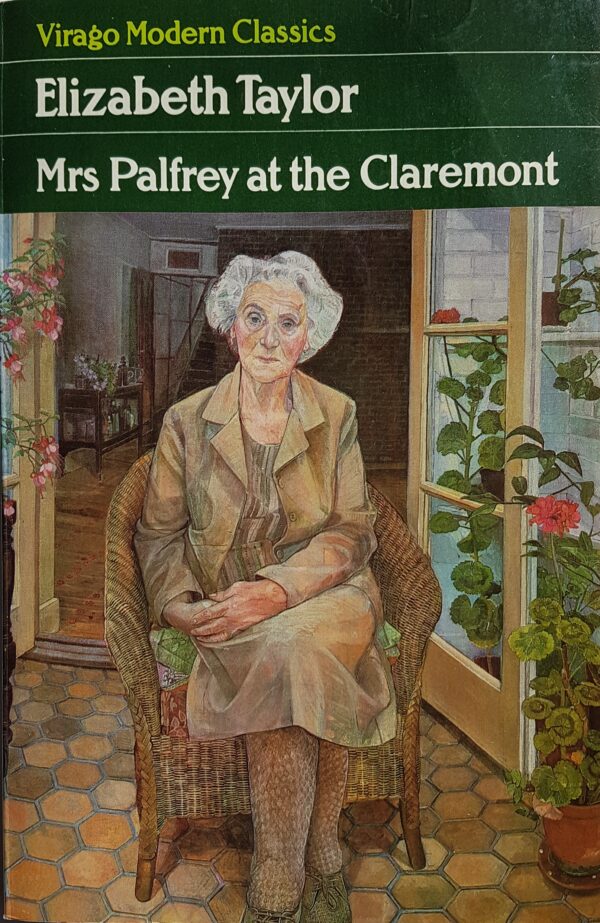

I couldn’t tell you how many times I’ve read Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont by Elizabeth Taylor (1971).

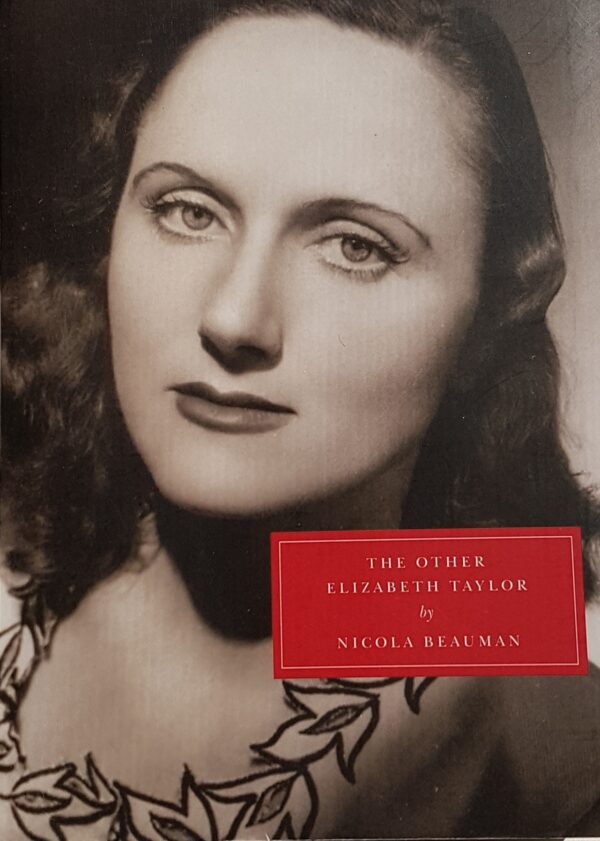

Not that Elizabeth Taylor.

This Elizabeth Taylor (1912-1975) was an English writer who published 12 novels and also wrote short stories, many of which appeared in the New Yorker. She was championed by friends like Kingsley Amis, Ivy Compton-Burnett and Elizabeth Bowen. And she needed champions because she was often panned by the critics, dismissed as a boring, suburban wife and mother with nothing to say for herself. Condescended to because she wrote about domestic

This Elizabeth Taylor (1912-1975) was an English writer who published 12 novels and also wrote short stories, many of which appeared in the New Yorker. She was championed by friends like Kingsley Amis, Ivy Compton-Burnett and Elizabeth Bowen. And she needed champions because she was often panned by the critics, dismissed as a boring, suburban wife and mother with nothing to say for herself. Condescended to because she wrote about domesticsituations. Even her prose style was deemed “feminine”. She was a “lady novelist” in the language of the day.

But we don’t have to accept that judgement.

I return to Taylor’s novels frequently, but Mrs Palfrey is the one I take from my shelf most often. It was her most successful novel, being nominated for a Booker. There was a BBC production starring Celia Johnson (of Brief Encounter fame) and eventually a movie, in 2005, with Joan Plowright and Rupert Friend.

Taylor always reminds me that no one is simply what they appear to be. Or, put another way, that appearance is always less important than substance.

Perhaps this is because Elizabeth Taylor was not who she appeared to be. This presumably staid housewife from the suburbs carried on a secret love affair for more than a decade, only ending the relationship to keep her family together. This apparently boring woman with no opinions had joined the Communist Party in the 1930s and retained her membership for decades. (My favourite story: She spent an annual holiday with Robert Liddell in Greece until the military coup of 1967, after which she insisted they meet elsewhere or not meet at all. It became a topic they couldn’t discuss. In his memoir of their friendship, Liddell derides Taylor’s boycott as a pointless folly.)

Taylor was a private person, or became one, but she knew it was only a mask of middle class respectability that she wore. And she brought that awareness to her writing, in her portrayal of characters, revealing their inner lives and stories. The substance behind the appearance.

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont is set in a small hotel with a clientele of the old, the lonely and the near-indigent. They struggle to maintain their independence and their dignity. They know and fear what awaits them as they age and their financial resources dwindle – illness or injury, incapacity, and the final admission to a nursing home or hospital where they will end their days.

Laura Palfrey is the widow of a British Colonial Administrator. We see her class position, her prejudices, her quirks and weaknesses but also her strengths, all revealed with subtlety and sympathy and a measure of humour. Mrs. Palfrey is no stereotype and neither are any of the other characters, whether their roles in the story are large or small.

On this reading, I pay closer attention to Ludo. An unemployed young man writing his first novel, he comes to Mrs. Palfrey’s aid when she stumbles in the street and becomes a stand-in for her absent grandson. Here is Ludo, the impoverished but attentive writer, arriving at the Claremont for dinner:

He came forward and kissed her lightly on the cheek. At the same time, he registered the strange, tired-petal softness of her skin, stored that away for future usefulness. And the old smell, which was too complex to describe yet.

I watch him closely. Now he is in the launderette, waiting for his clothes to dry, reading a novel by George Gissing. Who is George Gissing? A quick google search and I learn that Gissing was a Victorian-era novelist, author of New Grub Street. He wrote about people living in poverty, a poverty he had shared, and many of his characters were women. According to Judy Stove in The New Criterion, he considered that all of life was fodder for art. As does the fictitious Ludo.

A small, delicious crumb. I am grateful to have found it. Glad that I took Mrs Palfrey down from my bookshelf again.

Margaret Watson was raised on a family farm in southwestern Ontario. Like Elizabeth Taylor, she has a more famous name-twin, although the other Margaret Watson is a writer of romance novels and not a glamorous movie star.

Photos provided by Margaret Watson and Johnathan Ellul