What You Love

Introducing Isabella Wang

West Coast writer Isabella Wang made her print debut in TNQ 146 (summer 2018), as part of the gathering of “honourable mentions” from our 2017 personal essay contest. Then came her cross-country visit to Waterloo in March of 2018—and what auspicious timing. Not only did Isabella meet her fans and her TNQ family, she was able to join the Balderdash Reading Series, founded by Sanchari Sur at Wilfrid Laurier University, with poet Ashley Hynd, Anishinaabe and Métis trans girl and poet, Gwen Benaway, and Toronto journalist and poet Phillip Dwight Morgan. Isabella read from her TNQ essay, and in the Q&A that followed, sent a shout-out to her high school English teacher for influencing her formation as a writer. As for writing rituals, she cited calculus homework as a great distraction. “I think if you do what you hate, it drives you to what you love.”

Susan Scott, TNQ Nonfiction Editor

First, a word of context. Our practice is for judges to read all contest submissions blind, without knowing who the authors are. One detail in your essay, “Shortcomings of a Juvenile,” did stand out, though—you wrote that piece, you say, when you were 17, making you the youngest contestant TNQ has published to date. So, Isabella, tell us about yourself. How did you come to writing so early and with such verve? What’s the place of writing in your life?

I was born in 2000, in Jining, Shandong. I lived in Beijing, China for most of my early childhood, before immigrating to Canada at the age of seven.

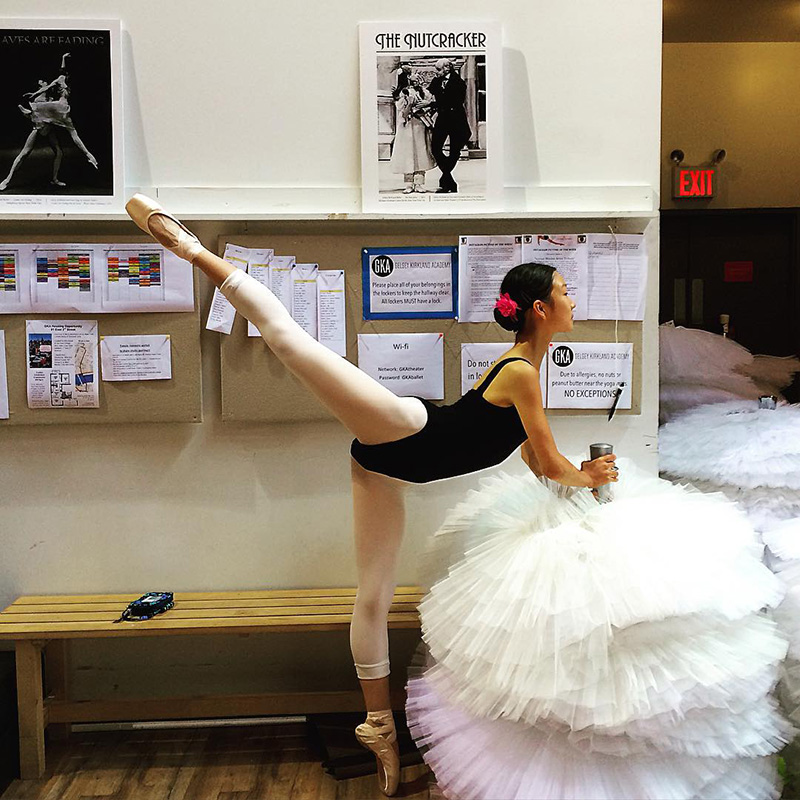

I wanted to be a writer, but was told that I could not do so by my parents, who didn’t think it a probable career path, and by my teachers, who told me I was a terrible writer. So I sought expression through movement instead. I dreamt of becoming a dancer with the American Ballet Theatre, and trained professionally in Vagonova-style ballet for years and years until that all failed horribly.

I am now an emerging Chinese-Canadian writer of creative nonfiction and poetry. I will be studying English Literature at Simon Fraser University in the fall of 2018, and interning at Room magazine, where I hope to engage and open up the literary scene to other aspiring, young writers the way so many people have done for me.

Your TNQ essay is a play on revelation and concealment. Some things you are frank about; others you allude to, nothing more. Tell us a bit about the back story—how and when you wrote the essay.

March of 2017 was a tense time. I had just left ballet, which I loved more than anything. I was grappling with my identity, struggling for a sense of purpose. What saved me were long hikes in the forest, which inspired me to write the essay. At the same time, I was applying for university, and was under immense pressure to go to an Ivy League university to study computer sciences or medicine. I was carrying 12 courses that year. My parents had forced me to enrol in every single science and math course. Out of stubbornness, I also took every English, literature, writing, and history course available.

I had written the intro and ending of “Shortcomings of a Juvenile” for an English assignment. When I wrote the extended metaphor, comparing people to trees, I did think of specific instances, but the body of the essay was taken from three different projects I had given up on, thinking they would never see the light of day. I didn’t even know what creative nonfiction was at the time, but looking back now, I can see recurring themes in my earlier work that would lay the groundwork for my writing later on.

Discovering your work in our big pile of submissions was a revelation. High school students are reading TNQ—wow, that’s fantastic! What drew you to something as specific as the Edna Staebler Personal Essay Contest?

It’s kind of a funny story. I was desperate, and the way I had rushed the essay reflected the sense of urgency from deep within me. With Grade 11 coming to an end, I didn’t have much time left, and I thought a publication would validate me to my family. Turned out, it didn’t, but it showed me that this was what I wanted to do, and I was prepared to fight for it.

I had no experience with creative writing, with CNF, or submitting, and I didn’t know of any magazines beyond the National Geographic and Time. It was pure coincidence that TNQ happened to be among the handful of places I submitted to that spring, along with other youth contests and (don’t laugh!) the New Yorker. I’m incredibly lucky in that sense.

I saw TNQ’s posting for a personal essay contest, and since the work I had written in the past all revolved around the same theme, I only had to put them together, edit my work, and within an hour I had submitted the piece.

Had I waited any longer, I would have lost the nerve and never submitted.

After submitting, I was on a high. For the next two days, I waited for a response, waited for my work to magically appear on the page. After that I gave up. This is it, I thought, this is the end. I’ll never become a writer. I totally forgot about it over the next few months. Over that period, I started getting rejections from other journals. By the time I got an email from TNQ, I automatically registered it as a rejection, and didn’t open it for two days. The email said I got long-listed. I didn’t know what a long-list was. I had to look it up on Google before I let myself believe it.

How has your writing process evolved?

My writing process now is so different from when I wrote “Shortcomings of a Juvenile.” That was written in parts and assembled in under an hour. Now, writing takes much longer. Process, for me, involves planning, writing a draft, and revising. I take time to plan things in my head, but I try not to think too much. I try not to discard ideas, though, either. I write them down and store them away. Sometimes, by the time I go back months later, my views have changed, and I have changed.

That doesn’t mean everything is lost. My experiences and content will always be mine to write about. They might just require another approach or angle.

If an essay is not ready to be written because it still feels too abstract and blurry, I’ll take more time to think, or let it sit, or do research to add depth to my own experiences. But sometimes an essay is ready to be written because I know its purpose clearly and it has a thread tying it together.

Even so, sometimes I don’t want to write it because I’m scared. That’s when I start pushing myself to get the first draft. Sometimes I plunge straight in, with minimal planning. That is what I find most terrifying, since I have no idea where the essay will lead, if anywhere at all, or what ugly truths I will unearth in the process.

It’s important to give yourself permission to write just for the sake of writing, with no certainty that you will succeed.

And success is relative. After writing a piece, I edit it until I feel I can go no further, until I love it and I feel like it’s the best thing I’ve written to date. Then I put it away for at least a month, during which time everything starts cracking. I start seeing holes in an essay that once felt so rich and tight. I go back and do another major round of revisions, then put it aside and revise it for another ten times before submitting.

Sometimes I start all over again, and that is okay, too, because I understand that my writing is developing and that I am changing so much.

I found the editing process with you quite remarkable. Apart from frequent, lively email conversations with you, each draft you returned had gained in clarity and depth. What was your experience of the process?

It was magical, this back and forth between drafts as we conversed along the way, getting to know each other over our shared love for the snow.

I learned so much about editing. Since money is tight and I can’t afford many workshops and classes, an opportunity for me to work with a mentor is rare. And English isn’t my first language, so when I edit myself, I can only rely on how the piece sounds, and I need someone to point out technical and grammatical errors so I know for next time. More importantly though, working with TNQ was the first time I felt anyone has appreciated my work, ever. I grew up hearing from my teachers that my writing was terrible. I remember handing in a Grade 4 writing assignment. My teacher told me that I shouldn’t have been allowed out of ESL in front of the entire class. It was humiliating. It made me never want to write anything ever again. Over the years, I lost confidence in my writing, and in myself.

My whole TNQ experience helped to restore my confidence.

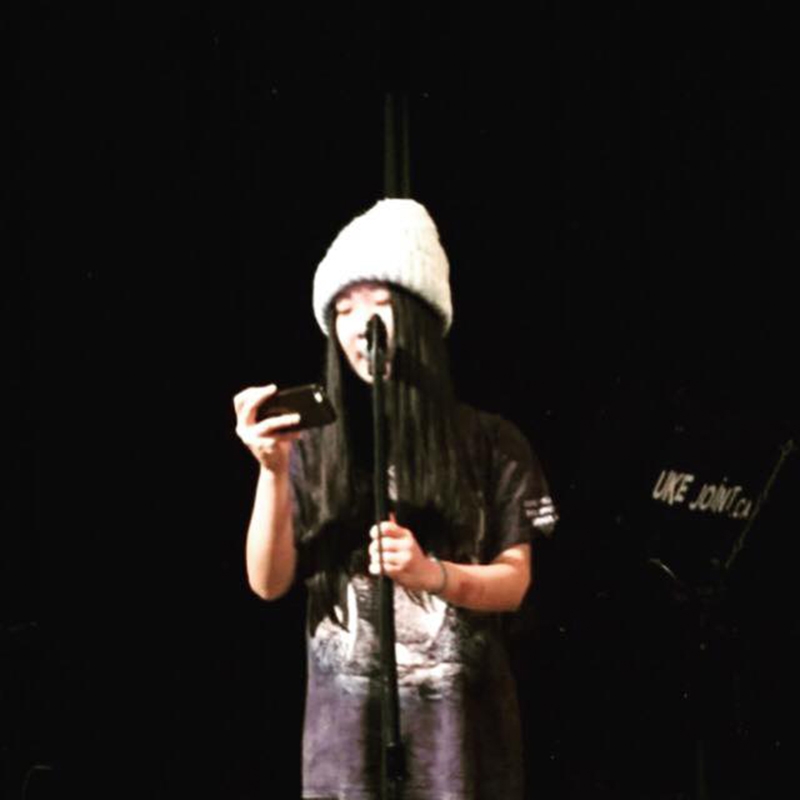

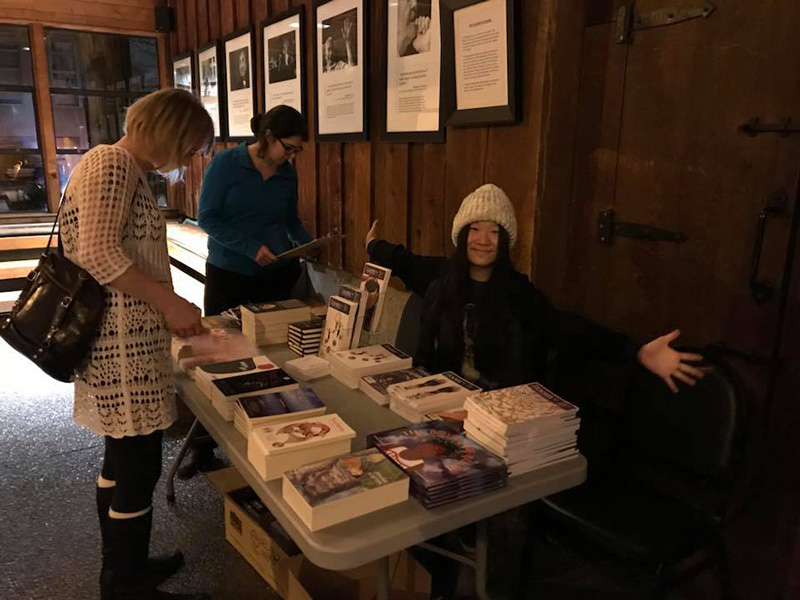

You’ve been taking your work public, doing readings, and so on, and when a space opened up for you at the Balderdash Reading Series, you stepped right in and embraced the moment. And a beautiful moment it was.

I couldn’t contain myself when I was invited to the Balderdash reading as part of my visit. I had been following Phillip Morgan’s work for quite some time, I had just heard Gwen Benaway perform her poetry while volunteering at the Growing Room festival in Vancouver, and my beautiful friend Ashley Hynd and I had connected in our own way. I also got to meet two people who are really special to me, Jagtar Kaur Atwal and Tamara Jong. All of us have stayed in contact. It was one of the most memorable nights ever for me.

We’d love to know who else you turn to for inspiration. Who are you reading? Which writers make you want to write?

My English teacher, who taught me in grades 10, 11, and 12, has been my greatest influence. He told me, “High school is meant for making mistakes. You mustn’t be afraid to push.” Days in his classroom turned into years. I kept on going back to his classes, trying to write “the perfect essay.” That never did happen, but I learned so much about writing in his class. My poetry mentors from SFU’s continuing studies program, Rob Taylor, Evelyn Lau, and Fiona Tinwei Lam, were the first people to introduce me to creative writing, and like TNQ, they believed in me from the start.

I wish I could list the names of everyone who has inspired me this year, but that list of acknowledgements is too long. I am literally in love with everyone. I read their books and flag their works in journals. And it’s the best when I meet them for the first time at events or on the streets. I get to scream in their faces and tell them how much I love them and cheer really loudly when they go up to read their works.

One thing that really made a difference for me this year is reading the works of Chinese-Canadian authors, Madeleine Thien, Phoebe Wang, Fiona Tinwei Lam, Jen Sookfong Lee, and Evelyn Lau for the first time, and then meeting them. I’ve read a lot of great books in the past, but I never saw myself reflected on the page. I think that comes to show the importance of representation. I grew up resenting my heritage because I was bullied so badly when I came to Canada. Even when I was writing, I wrote to escape my own body, to pretend I was someone else, and not Chinese. Seeing these writers, and reading their works helped me embrace that part of who I was, dig into myself, look into my past, my family’s history and where we came from. Believe me, I’ve dug deep.

“Shortcomings of a Juvenile” will, we believe, inspire emerging writers—that’s one reason why we took on a chance on it and on reaching out to you. But it’s a work that should also be read by seasoned wordsmiths, because it reminds us what’s at stake, starting out—what’s at stake when writers are struggling to find their footing. In closing, would you like to speak to that?

I was really nervous starting out, apprehensive over how I would be perceived. I didn’t know if I would be accepted or even be taken seriously, given my age. For a while, I feared calling myself a poet in front of other poets because I didn’t know if I fit those qualifications, and I didn’t want to offend anyone. I questioned whether there was a place for me, whether I had the right to tell my own stories because there were so many writers who have been doing this for much longer than I have, and who I felt were more skilled, more equipped and experienced than I was.

I was also hesitant about pursuing writing as a career. It was a big decision to have to make at 17, especially since I had only made my departure from ballet two years prior. I didn’t know if I was ready. I was afraid to give myself permission, knowing what I was in for, and aware of exactly what the consequences could be if I weren’t careful enough.

When I was a dancer, I was training 364 days a year, 45 hours a week, for six years. It was because the stakes were so high, and I had given so much, that not succeeding simply wasn’t an option I was willing to consider. But I was so young when I entered the professional world of ballet, I made mistakes and took shortcuts that ended up costing me everything.

Those past mistakes were still haunting me when I made the transition to writing and started to become more involved in the literary community. It was a decision I made, thinking that whether it’s arts or sciences or medicine, and whether you are starting out or are already established in your field, the stakes will be high, regardless. In the end, the lessons I took from ballet are what I have to guide me, and at least this way, I’m doing what I love.

Doing what you love—that so clearly comes across in your writing and in your warm exchanges with other writers. Thanks so much for joining us Isabella, here, now, and in the future.