A Conversation with Linda Hatfield, Runner-Up of the 2023 Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest

By Barb Carter, Linda Hatfield

Barb Carter, Consulting Editor of The New Quarterly, sat down with Linda Hatfield, who’s poem “Mondays with My Dad” was the runner-up of the 2023 Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest.

Barb: As a former Lead Poetry Editor of The New Quarterly, now a Consulting Editor, I continue to act as a poetry editor and help select poems for publication in the magazine. In addition, I have the privilege of helping adjudicate the Occasional Verse Contest. I cannot express what a gift the latter responsibility is. Finding a poem like “Mondays With My Dad,” among this year’s entries and celebrating its choice as a winning poem makes my position with the magazine a joy.

Linda, your poem resonates with me more than I can say. It brings back to me visits to my now deceased mother-in-law at a nearby nursing home. My mother-in-law was an unexpected gift when I married my husband. I grew to love her deeply over the years of our marriage (forty-three… my husband passed away in 2012). She was a gentle active woman well into her nineties. Picture a white-haired independent grandmother up to her elbows in flour, baking special shortbread cookies for her grandchildren and brim full of stories to entertain them when she came to visit and/or babysit at a moment’s request. I watched my husband’s heart break a little more with each visit to the nursing home where we placed her, having moved her from Windsor (where she resided) to Kitchener where we had made our home. We wanted her close to help try and ease her descent into dementia. We couldn’t. The poignancy of your poem underlines the insoluble dilemma of being unable to help her. Your candid poem, well-crafted and moving, encourages one to return to it again and again, discovering a relatable nuance each time.

I like the familiarity of the title. It reminds me of Mitch Albom’s book, Tuesdays with Morrie. Can you tell me how you chose it?

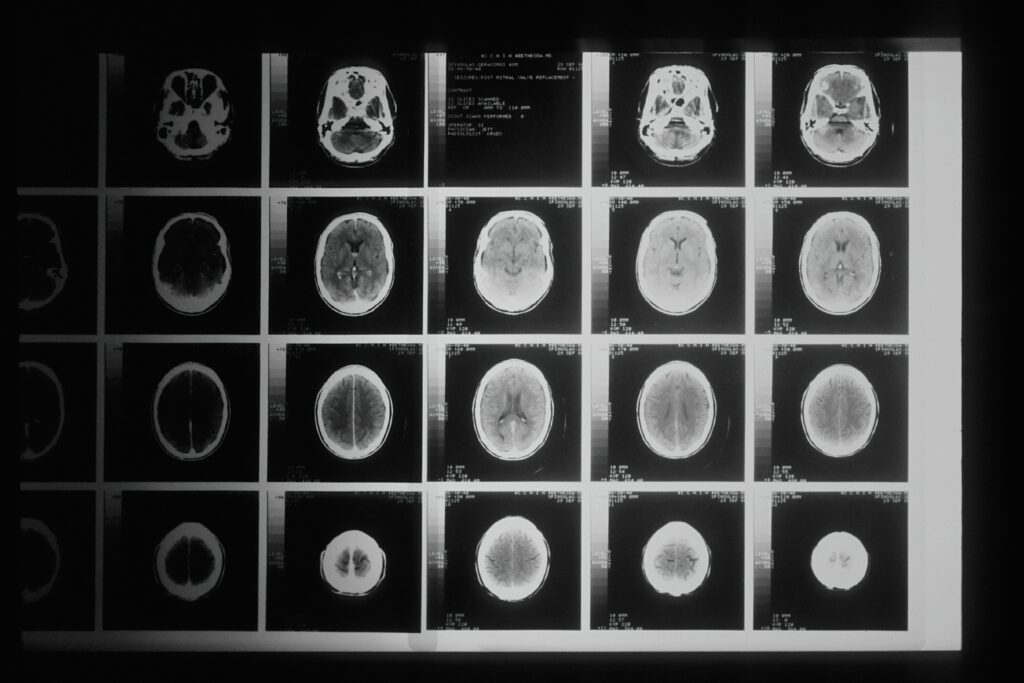

Linda: My father, a physician, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 1995. He saw his own MRI and knew that he was “done for”. Dementia is a cruel disease that results in ever diminishing language skills, behavioural and mood changes, and of course, fading memory and cognition, all of which makes for awkward visits. Early in the journey, my family (four girls and my mother) were struck by how quickly we all felt abandoned by our support community. When Dad was placed into long-term care in 2001, very few friends or family members felt comfortable spending time with him. Determined to be there for him, we daughters each took one day of the week, and my mother took the remainders to ensure he had contact with a friendly face every single day.

I am familiar with Tuesdays with Morrie, and acknowledge the connection, although it wasn’t intentional, at least not consciously. I was simply trying to capture the ritual of my weekly visits. My assigned day changed over the eight years he was in care, so Monday isn’t significant in any intended way. It was always a weekday, though, and as I was a full-time teacher back then, it always came at the end of a long and often challenging day of work. So, my “Dad Day” was wrapped up in a complicated sense of duty as his daughter, of being a “team player”—supporting my mom and sisters—as well as a deep love and desire to ease the isolation, in some small way, of a man who had always been there for me.

Barb: The title is gentle, quotidian. The reader eases into the poem, but immediately the first stanza grips the reader, as she acknowledges the plight of the speaker: Duty calls and I reply,/battling buses and exhaust,/ exhaustion and resentment. Mondays with Dad are not necessarily pleasant occasions. And then the final four lines startle the reader into recognition with the subtle religious overtones that will move throughout the poem. The speaker is heading to a place called Bethany, where some say the (nearly) dead/can be temporarily raised/by the miracle of visitation. How would you describe the tone of your poem, the intent of those four lines?

Linda: From the outset, our experience of long-term care was filled with frustration and concern. Three of us worked in the education system and were appalled at the lack of programs for dementia patients. Amongst ourselves, we described it as “death by boredom”. Residents were often ignored or forgotten, left sitting in hallways with absolutely no stimulation.

These lines attempt to capture the sense that our visits with our dad not only raised his level of engagement with the world, but also raised the hopes and spirits of anyone around us who would hear our chatter or singing or other efforts to stimulate a response from our dad. We befriended many of the other residents on his floor (not all of whom had dementia) and made efforts to acknowledge and honour them. Seeing them respond to our care and attention, however briefly, felt truly miraculous. The fact that his care facility had Bethany in its name was a gift in terms of expressing the concept of reanimation.

Barb: Tell me about the use of parentheses. I admire your clever use of whispers under the breath. I like how they continue throughout the poem.

Linda: Thank you! As the poem unfolded, I found myself needing/wanting to add depth to the story I was telling but didn’t want it to feel too cluttered or wordy. I found the parentheses useful in providing that detail as a kind of interior dialogue—or sidebar whispering as you worded it. It also serves to emphasize that there was next to no back and forth to the communication with my dad; he was unable to speak for at least the last five or six years of his life.

Barb: Stanza two is excruciating in its all too intimate sensual detail of the nursing home: the smell of loneliness, /the sounds of helplessness,/and the walls the colour of neglect/in the catacomb rooms of long-term care. Why catacomb rooms of long-term care? Is there an intended echo back to the stanza that comes before?

Linda: Yes. The reference to raising Lazarus in ancient Bethany and to that time in early Christian history when burial tombs were hidden from the Romans is intentional. The image of the cramped, partitioned chambers of the catacombs is intended to be a metaphor for Lazarus’ tomb as well as the tiny rooms within a long-term care facility, in which residents are largely left alone —their “resting places”. Those rooms affect a kind of burial of who they are/were before they came to long-term care. I visited the catacombs of Rome when I was young, and I remember the winding corridors as dark and bleak, hidden from the light and joy of the living world. I couldn’t wait to leave them, and I confess I often felt the same way about my dad’s facility. Every visit was an act of will, to overcome the trepidation. So many people would say, “I don’t know how you do it.” While meant to be sympathetic, comments like this one often stirred anger, instead. It was no easier for my family and me than it would have been for them. But my love for my father would not allow me to give in to self-pity or self-preservation. Being abandoned is my number one fear. I couldn’t let that be his experience.

Barb: Anyone who has visited a long-term care facility recognizes the speaker’s walk through the halls to find her Dad in stanza three. What do you hope we learn about the speaker in this stanza?

Linda: I am a huge empath. I easily take on the pain and anxiety of others, to my detriment. I hope readers can sense that burden, and themselves chafe at the thought of those poor souls simply sitting there, desperate for attention. Walking past them on my way to see my dad was one of the most difficult parts of my weekly visit. It would have been easy to blame the staff, but that is not fair. The work of caregivers is undervalued and underpaid. Their inability to fully address the needs of their clients is a systemic problem. And, based on my more recent experience with my mom in long-term care, not one that is going to get better soon.

Barb: I am moved by the intimacy of your poem, the candour, the diction so aptly chosen. Stanza four reveals tenderly the love of the speaker for her father. Seeing his face lit by the afternoon sun–/looking less his eighty years elevates him from the other residents. As the description of him continues in stanza five and six we learn he has soft hands and a gentle touch. And then the big reveal occurs in stanza six. Dad was a doctor. How fiercely ironic that he could not heal himself. For whom should the listener/reader feel more sympathy, the father or the daughter?

Linda: I wouldn’t want one to garner more sympathy than the other, in all honesty. The plight of both was excruciating. It’s impossible to know how my dad truly felt about his circumstances; I don’t believe he ever imagined that he’d find himself there. He was a well-known public figure in our community—a pioneer in the field of medical ethics, dying with dignity and treating the whole person. He was a BIG presence—and I don’t believe his ego ever allowed for the possibility that he would fade into obscurity. I’m sure when he first realized his fate, he was as terrified of what lay ahead as we were. At some point, however, he was no longer aware of what was happening while we were not spared. Still, our family believes that through it all, there were moments of grace—given and received—in a touch or smile, a moment of emotional or spiritual connection, if not an intellectual one. That’s what got us through it—believing the man we knew and loved was still “present” and had something to offer.

Barb: Is the poem about the speaker or the father? It is she who paints the hell on earth in which he lives. The allusion to the raising of Lazarus in stanza one haunts the poem. How badly does she want to be the angel she imagines him expecting…/to rescue him from this purgatory?

Linda: I believe the poem is about both of us, about the most basic elements of human connection and the bond between parent and child. In writing it, I felt the need to be his witness, one who was accompanying him on his journey who could testify afterwards to his courage and humility.

The possibility of an angel watching over him provided me a source of comfort and wonder. He really did often look up and over my shoulder, as though focused on another “presence”. If an angel, I imagined that he might welcome it to set him free. Each visit pulled him a tiny step back from that precipice, so perhaps we were keeping him from that release. I did have dreams in which my father was cured, that he was raised from the “death” of his mind, that his disease was no longer a chasm that separated us. So perhaps I, too, subconsciously wished for that angel to lead him gently away.

Barb: We see the interaction between the two through the daughter’s eyes. We feel him gently stroking her fingers…silently counting the joints/like a bone-bead rosary, /examining the upturned palms,/his touch, a wordless prayer. What a powerful, brilliant simile. Is she or is she not a believer?

Linda: I was raised in the United Church, a denomination with a liberal and progressive view of Christianity. I was very involved in my congregation, in youth groups, choir and serving on committees. I also attended a post-secondary, four-month program living in community and exploring faith with other young people. These experiences helped me to formulate my set of beliefs. Although many of the religious images in the poem reference Catholic terms or practices, I personally, embrace a very ecumenical understanding of faith and find beauty and meaning in a variety of spiritual traditions. My father was also raised in the United Church and was very much a man of faith, and yet also a man of science. That particular image attempts to demonstrate the meshing of the two—the doctor performing a ritual that is at once physical and spiritual. It also represents “old memory”, the last bastion against the ravages of the disease.

Barb: How well the poem is crafted, constructed effectively to build to its understandable, but devastating climax. Immersed in the reality of the long-term facility once more, we visit with them the table /where supper is served/in blobs of muted hue/(unrecognizable), /bathed in gravy. But it is the final religious allusion that devastates.

…

Like a penitent bird, his mouth opens

and I offer him a bite,

(his body, broken)

and then a sip

(his blood, shed)

a strange Eucharist, this—

a communion of souls

without words,

without blessing,

on Mondays with my Dad.

Please comment on the deft conclusion of your poem.

Linda: At some time in my teens, I developed an understanding of the eucharist (communion) as the defining moment of Christ’s life, proving his divinity and humanity at the same time. It is both a deeply religious ritual that hints at the promise of eternal life, and the acknowledgement of a most basic human need: the communal sharing of food. I remember often feeing that feeding my dad also embodied those two realities: at every meal given with love and tenderness, not only was he the recipient of physical nurture, but of spiritual nurture as well. It felt like a “holy” experience.

Barb: What prompted the writing of Mondays With My Dad? Is this poem a stand-alone or part of a series?

Linda: I have written a few other poems about my experiences with my father as he struggled with Alzheimer’s. Almost all of them have a spiritual dimension and religious references. I think I wrote them to capture the feelings of those years in a way that is deeply personal, but perhaps also universal—something others (like yourself) who have undergone a similar journey can appreciate. Writing poetry is cathartic for me.

I have also written a few poems about my mother’s experience with dementia and long-term care. They may one day make it into a collection that I’m building of other such spiritual experiences in my life.

Barb: What are you writing now?

Linda: I am part of a writing group called The Espresso Poetry Collective. We gelled after taking a class together just before the pandemic hit and decided to self-publish an anthology called “Uncommon Grounds”. We continue to meet regularly to workshop new poems and are considering putting together another anthology in the next couple of years. I belong to another, less formal writing group that meets periodically to workshop other genres of writing, as well.

Since retiring seven years ago, I have also embarked on writing a Creative Non-Fiction/Memoir about my mother, her mother and grandmother, and their influence on my sisters and me. My Grannie died when I was just a year old, so I didn’t know her, and my mother never knew her own grandmother. But we have come to believe that we all share/d similar traits. I am attempting to examine these connections between women generations apart, and how biology and life experiences translate into behaviours/personalities that are passed down. It’s been a fascinating dive into my personal history and how the lives of my ancestors are still impacting my own life today. I hope to bring it to the finish line in the next couple of years.

Linda Hatfield is a retired teacher who has been writing poetry since she was a teen and has begun penning a CNF/memoir. Her poems have been published in the ARTA magazine, the YYC POP online exhibit, and the Wine Country Writers’ Festival Anthology in 2021. She is a member of the Espresso Poetry Collective, who self-published an anthology called Uncommon Grounds during the pandemic. When not engaged with the written word, Linda loves to read, travel, garden, and create with paint, fabric and photography. She lives in Calgary with her husband, Rick Smith.

Photo by David Sinclair on Unsplash