Finding the Form with Jessica Moore

By Jessica Moore

One day in the second lockdown winter, when my twins were nearly three, I was walking to the office – my office is a small room in a brutish 70s building downtown, with very thick walls and one window that looks out onto a tree and a patch of sky. It takes me about an hour to walk there from home, so I have lots of time for thoughts. This particular day I remember I had noticed a hair elastic on the ground – I so often see lost elastics and think of Annie Dillard’s wondrous passage about pennies and abundance, and more than once on a windy day I have stopped to pick an elastic up from the ground and pulled my hair into a ponytail to keep it from whipping in my face, a habit that makes my sister and my mother grimace, but what could really be so wrong with an elastic on dry concrete, and why waste your money, I tease them, when the world is fairly strewn with elastics

Around the halfway point to the office I had also witnessed a moment that made me grimace inwardly, outside the Harbord Bakery, when a middle-aged woman bent down to drop a coin into the hand of a man sitting on the sidewalk. He had a very soft-looking brown beard and reminded me of a video artist I know. It was the way the woman so urgently avoided skin contact that made me want to look away, and I suppose also the performance of abundance and lack in this city that is driving artists and others so steadily out (or into the ground), untenable, and who will be left when only the rich can afford to live here, and what kind of city are we already creating.

Thoughts of scraping by made me think of gleaners, and about how things in plain sight can still be invisible, at least to most eyes. I thought about the back-alley vision some of us – dumpster divers, for example – must have of this place. And then I got to thinking about Agnès Varda because she is one of my favourite artists to think about, and because her documentary The Gleaners and I inspired me so deeply when I first saw it, elevating as it does these practices, bringing in an awareness of waste and a gleam of delight.

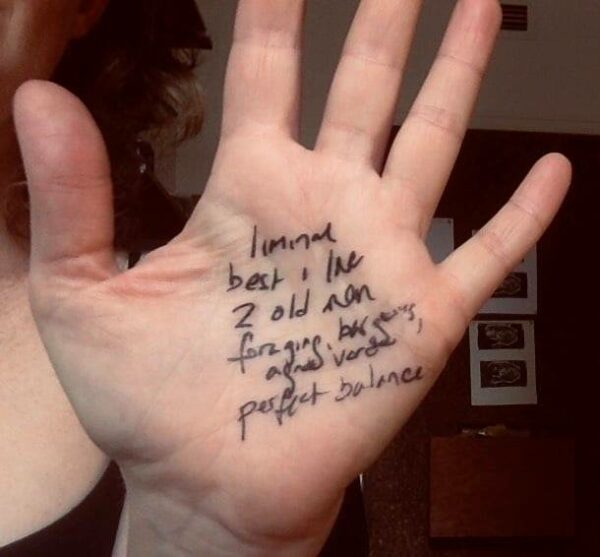

I didn’t have my notebook with me on that walk so I took out my pen and wrote on my palm a list of vagaries floating in my mind: liminal; best I love; 2 old men; foraging, bargaining, Agnès Varda; perfect balance.

I suppose most of my thoughts for the book have come in these jumbled, palms-full, jostling annexed fragments that I try out alongside one another to see what resonates when they are in conversation. Metonymy is one of my favourite literary devices.

Jessica Moore is an author and literary translator. Her first book, Everything, now, is a love letter to the dead and a conversation with her translation of Turkana Boy by Jean-François Beauchemin, for which she won a PEN America Translation award. Mend the Living, her translation of the novel by Maylis de Kerangal, was nominated for the 2016 International Man Booker and won the UK’s Wellcome Book Prize in 2017. Jessica’s most recent book—The Whole Singing Ocean—is a true story blending long poem, investigation, sailor slang and ecological grief, and was longlisted for the League of Canadian Poets’ Raymond Souster Award. She is currently at work on a memoir about the intersection of motherhood (to twins) and art.

Photos by Jeff Frenette on Unsplash and Jessica Moore