Finding the Form with Lisa Alward

By Lisa Alward

My story ideas usually begin with an image, a mental picture of something I witnessed or experienced or that someone told me about. For “Little Girl Lost,” that image was a young girl’s sullen face pressed up against a window.

My father’s family were related, through marriage, to the Saint John artist Miller Brittain. Once, in the early 1960s, when my father was back in Saint John for Christmas, his mother asked him to drive a box of presents to Miller’s house, out near the airport. But when he got there, Miller wasn’t home. Just his nine-year old daughter. Miller’s wife, Connie, had been dead for several years by then and the house by my father’s account was a wreck, but what unsettled him more was how odd this little girl seemed. Not in the least friendly or polite, or worried about being left all alone in a falling-down house while her father was likely out boozing (Miller Brittain was a well-known drunk). My father might have used the word feral, or maybe I thought of that later on my own. All I know is that this tiny sliver of a story, a strange little girl living with her alcoholic artist father, stuck with me.

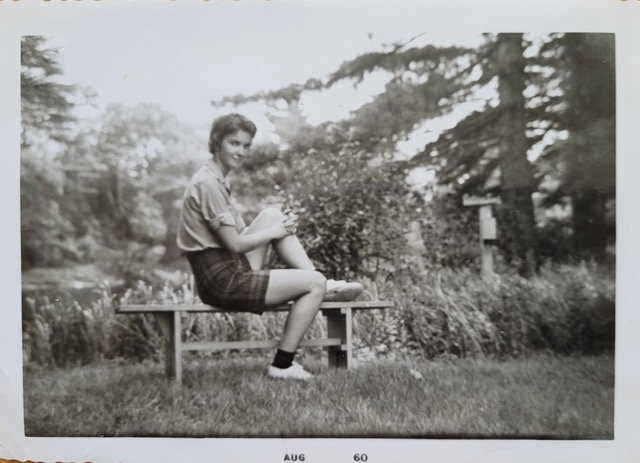

Ten years ago, when I began writing fiction, I thought about doing something with this material. What if, instead of my father, my mother had been the one to drive out to Miller’s house with the box of presents? Maybe a year or so after their marriage or during their engagement, and possibly in the company of my father’s mother? I made some notes in a computer file. I pictured the sullen face in the window. This, I decided, would be the story’s final image. A moment of ambivalent connection between the girl trapped in her father’s house and a young woman trapped in an engagement or new marriage that she’s worried isn’t right for her. I pictured my mother turning back to look at the little girl in the window as my grandmother drove them away. I gave the story idea a draft title, “The Artist’s Child.”

Years went by. I can see now that I wasn’t ready, that I didn’t have all that I needed, yet for a long time those two or three sentences in my “Stories” folder felt like a false lead. I didn’t like to look at them and buried the file deeper inside another folder.

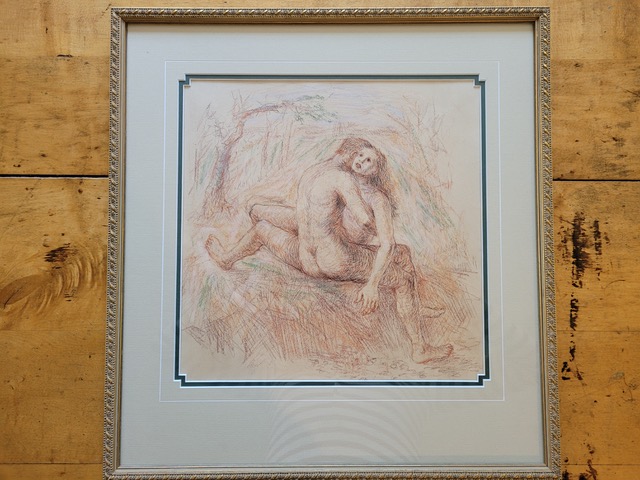

Years went by. I can see now that I wasn’t ready, that I didn’t have all that I needed, yet for a long time those two or three sentences in my “Stories” folder felt like a false lead. I didn’t like to look at them and buried the file deeper inside another folder. Then during the pandemic, I made an impulse purchase. I bought a sketch by Miller Brittain. The gallery where I saw it had dubbed this charcoal-pencil drawing, which features a naked couple embracing, “Adam and Eve,” but I instantly recognized my distant relative Connie Starr as the vacant-looking woman being embraced and Miller as the man clutching her rather desperately on his lap, and it struck me that whatever was going on between them had more to do with human love than Original Sin. Around the same time, I learned that Miller’s daughter, Jennifer, had died, sending me down a Google rabbit hole and ultimately to the NFB website where I found Kent Martin’s moody documentary Miller Brittain, which includes clips from an interview he did with her in the 1980s, and to the book Miller Brittain: When the Stars Threw Down Their Spears, with its interesting essay on the influence of William Blake on Miller’s art.

I now had considerably more material than I’m used to having at the beginning of a story, including another haunting image, one that I could actually gaze on as I wrote, since it hangs in my living room. My story’s form, however, still eluded me. I’d initially imagined it as one long scene ending with the image of the artist’s child: her small pale face pressed up against the grimy window, my young fiancée staring back at her. Now, I toyed with a more complex structure. What if the character inspired by my mother were to meet the artist’s child two more times? Her life story punctuated by these three chance encounters? But this began to feel contrived. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to happen between them, especially in that third and final encounter. Then I remembered one of the odd details I’d learned about Miller Brittain in my research. How on bombing missions over Germany, he’d always carried a copy of Blake’s Songs of Innocence in the breast pocket of his uniform. There was something ironic, self-mocking even in this gesture. (His role on the plane was to aim the bomb.) I thought about how in Blake innocence and experience are intertwined, neither state fully as distinct from the other as it appears on the surface. I pulled down my own copy of the Songs and found two poems we hadn’t covered in my third-year Romantics class, “Little Girl Lost” and “Little Girl Found.” Suddenly I had my form. Two scenes, two encounters with a stranger, set seventeen years apart. Innocence and experience.

“Little Girl Lost” is Lisa Alward’s fourth story for The New Quarterly. A past recipient of the Peter Hinchcliffe Award, her short fiction has appeared in Best Canadian Stories and The Journey Prize Stories as well as journals such as The Fiddlehead, Exile Quarterly, Prairie Fire, and untethered. Her debut collection, Cocktail, will be released by Biblioasis Press on September 12, 2023.