Finding the Form with Wendy Donawa

By Wendy Donawa

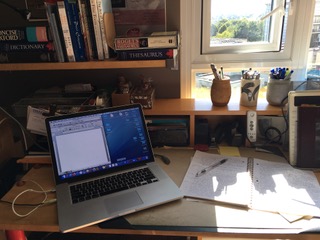

The window at my desk overlooks the blue slump of the Sooke hills; beyond, the Salish Sea surges around Vancouver Island’s south coast. I write my poems here, in a small condo angled toward sea and sky, on the traditional territory of the Lekwungen (Songhees and Esquimalt) peoples.

“Eye of God” was finished and submitted for publication before Covid-19 and George Floyd’s murder. But even without those two tragedies, viral and racial, ample impetus for distress has been provided by a relentless news-flow of desperate refugees and environmental degradation, of our own country’s obtuseness about inequity and racism, and of the relentless surveillance of the algorithm that seems to contain us.

My poems tend to the lyric, or narrative lyric, often in free verse. But sometimes a theme asserts itself that requires a particular structure. This poem gradually morphed into a pantoum. Its repetitious structure is good for a rant, and I was in a rant-ish mood. But a rant is not a poem.

How to remain porous to the wretchedness of the world in this troubling and unreadable historical moment? How to find those grace-notes of compassion and beauty that animate and energize a poem?

When I finally settled on a title, the poem found its controlling metaphor. The Eye of God nebula, its splendor in an unfathomably vast universe, suggests ancient beliefs in a compassionate deity who “sees the little sparrows fall” amid the world’s misery. The Mexican ojo de dios is a woven votive believed to protect children.

But Opus Dei is also a sinister and secretive organization. Its present-day parallel is the digital universe’s constant surveillance, banal as a messy kitchen drawer, but documenting every aspect of our lives, served by flotillas of drones and security technology of every description. The narrator’s mundane “life’s minutae” is coded by some watcher, motive unknown, and evoked the contrasting image of a Book of Days, the exquisite illuminated manuscript format that guided the medieval faithful—a far cry from the coder’s jumble of “pencil stubs and unsorted baseball cards”.

Because I don’t think clearly on a screen, poems go through multiple penciled iterations on yellow-lined foolscap before I print and edit until form and content cohere. At this point editing becomes a continual reading aloud for cadence, for the doubled implication that repetition brings, for line breaks that control flow, for musicality that doesn’t get singsong-y from duplication.

I love the way pantoums accommodate shifts in meaning. I can fiddle a bit with syntax so that line breaks allow startling disparate images (“…conspiracy theories/pencil stubs…”; or “…swans, and/Rohinga….”). Repeated lines reflect on one another: “Yet there will be judgment” suggests divine will, while the following line “while drones scoured forested borders…” implies oppressive legal regulation. It all circles back to the beginning, like the narrator, still trundling her burdensome luggage into the dark.

Wendy Donawa grew up in Victoria, but spent most of her adult life in Barbados as an artist, college teacher and museum curator. Since her return to BC’s salty coast, her poems have appeared in magazines, anthologies, and her three chapbooks. Her first poetry collection, Thin Air of the Knowable (Brick Books, 2017), was a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award, and her forthcoming collection, Our Bodies’ Unanswered Questions, will appear (Frontenac House) in 2021.

Photos courtesy of Wendy Donawa and Angelina Litvin.