From the Banks of the Grand

One of the short-listed essays in the 2011 Edna Staebler Personal Essay contest, Geoff Martin’s “From the Banks of the Grand” traces the history of Block II, a parcel of land in what is now Waterloo County settled by his own Mennonite ancestors under deeds that were illicitly issued, a swindle that only came to light when the debt owed on the land surfaced. He begins digging into this story of frontier injustice done to his own people only to discover a deeper history of injustice done to the Haudenosaunee, or Six Nations of the Grand River, to whom the land belonged until they were maneuvered into selling it at a time of great privation and duress, and who were never adequately compensated. But, as Martin discovers, “the past is never past,” and these overwritten or neglected histories have a way of outing. He ends by examining his own conscience, his own complicity of silence, in the oppression of others. It is a beautifully written, conscientiously researched essay framed by a personal history of connection and dislocation. And it is set in the community where The New Quarterly also makes its home. Though we didn’t have the space to publish it on the page, we asked Geoff’s permission to make it available online to our readers and our community.

When the coffin hit dirt, my mother’s cousins slackened their ropes, untied the knots, and pulled the frayed ends upward into the sunlight. Several shovels were passed around, from family member to family member, and the hole slowly began to fill. The repeated, resonant sound of earth dropped on wood sounded out, like a cracked bell, through the cemetery.

It thuds for thee.

The internment of my great grandmother certainly felt old-fashioned. I’m used to the mini-putt turf and the brass cable mechanism used by funeral parlours to mask the messy logistics of interring a dead body. But this was my first, and quite likely my last, Mennonite funeral. My great grandmother’s children and their children’s children have all left the conservative church, gravitating to a variety of more modern or more evangelical persuasions. Funerals have a way, though, of bringing together a variety of different affiliations, reminding all attendants of their interwoven histories. Which was why I found myself, in August 2006, standing silently, suddenly, behind a yellow-bricked Meeting House on an old river road east of Elmira, Ontario.

Half a kilometer farther east, across the sloping field beyond the cemetery, the Grand River courses quietly below a ribbon of spruce and pine trees, breathless from its tumble through the Elora Gorge. Just past Line 86 to Guelph, the river curves back upon itself and flows beneath the covered bridge at West Montrose, where it soon collects the slow waters of the Canagagigue that have bent their way south-east from the industrial edge of Elmira, my hometown.

That creek’s name remains something of a mystery around town. I’m told by some, with a shrug, that it “sounds Indian,” and I’ve seen it danced out, with brooms and steel-toe boots, as the “Canada Jig”; neither interpretation, however, adequately plumbs the depth of its original meaning—a meaning now fully submerged, apparently forgotten.

Further south of Elmira, the Grand River commingles at various points with the tributary rivers of the Conestogo, the Irvine, the Nith, and the Speed. After wending its way southward past Kitchener-Waterloo and Cambridge, the Grand sweeps through Paris and hooks through Brantford before dividing the Six Nations Reserve on the northwest from the town of Caledonia on the southeast. Eventually, at Dunnville, the Grand River sheds the accumulated waters of 6,800 square kilometers into Lake Erie for passage down Niagara Falls to Lake Ontario and through the Saint Lawrence to the continent’s edge, where it surges out into the Atlantic Ocean.

It’s a circuitous route that ties together disparate communities of people who live by the water’s edge. Each place-name, along the way, evokes a distinct history, a pattern of settlement, a raison d’être. These place-names stock the river with human value and make the waters flow with social, political, economic, and environmental importance. In this respect, the Grand River channels a sort of liquid lineage, an archive we can trace backwards; it’s a watery inheritance that belts together large expanses of time and space.

In front of the Mennonite meeting house, newer, colored vehicles sat side-by-side with older, uniformly black models, while rows of horses waited patiently with their buggies at the line of hitching posts; the parking lot was a remarkably catholic scene for a people whose theological heritage marks them as protestant of the Protestants. Behind the Meeting House, meanwhile, I stood tightly with my great-grandmother’s non-Mennonite descendants around her open grave. Encircling us was the much wider gathering of her Mennonite church community. A circle within a circle, amidst the uniform rows of white, slab gravestones, bearing simply the names, the birth dates, and the death dates of our collective ancestors lying beneath our feet.

An open grave, with its exposed soil and its hollow ache, calls attention to the stories that explain how a person and a people-group come to rest on such a precise spot of earth. Funerals often help those stories resurface; they seem to haul up into the light of day stories that hook onto the frayed ends of the rope of history. What we make of these stories, and how we piece them together, shapes the way we understand ourselves and our communities; our stories, in other words, generate a sense of place and a responsibility to that place. Like needles and thread and conversation at a quilting bee, the narratives we repeat to each other work to suture together diverse pasts and diverse presents. They produce a culture.

In the weeks and months after the funeral, for instance, my great grandmother’s descendants shared stories at kitchen tables and on living room sofas. These accounts bundled together various personal memories with a collective sense of received history. Throughout these conversations, I listened with renewed interest to tales about the early Mennonite migrations from southern Pennsylvania to Block II, the heavily forested hinterland of Upper Canada. What began as a trickle of settlers in 1800 became a flood by the late 1820s, as the Pennsylvania Dutch Mennonites sought out cheaper land and followed north the British Crown’s assurances of military exemption. From the expansive forest of the upper Grand River watershed, the Mennonites hewed the lumber for house, barn, and fence. They proceeded to cultivate the newly cleared land and opened up, in the process, what became the County of Waterloo. It is a story of faith and trust, resourcefulness and industry, daring endeavour and blessed triumph.

And yet funerals sometimes also bring stories to light that have been otherwise intentionally or unconsciously buried within the sedimented layers of time. This happens, most especially, with family secrets dislodged by death. But it happens, too, with larger cultural narratives—voices breaking in upon the usual patterning of events retold, haunting about the quilted margins of our narratives, interjecting complexities and disturbances into our otherwise tidy needlework.

That same year, forty kilometers downstream from my great grandmother’s meeting house, a contentious and, at times, violent land dispute exploded on a housing development site situated between the Six Nations Reserve and the town of Caledonia. News reports of road blockages, police arrests, depressed housing prices rippled up the Grand, seeping worry through the rural farmlands and urban foundations that bordered the waterway. Each report carried with it the revelation, for most of us, that the Six Nations’ claim to the twelve acres at Douglas Creek Estates was but a small fragment of a much larger, original land grant—one that encompassed six miles of land on either side of the river, beginning at its mouth at Lake Erie and extending north to the headwaters beyond Orangeville. It’s an expansive, twenty-kilometer-wide tract that cuts up through the province of Ontario, enclosing a population of more than 650,000 people and sundering the Greater Toronto Area from the London-Windsor-Detroit corridor. In town and at the funeral that summer, ‘Caledonia’ conjured a range of reactions, varying from astonishment to disparagement to angered hostility; that a tract of such magnitude could have any bearing on contemporary Ontario was regarded as sheer presumptuousness, as utterly preposterous. If land claims and Indigenous issues were matters for the department of Indian and Northern Affairs, what was this, we wondered, coming from the south? The story floating up, against the current, from the Six Nations Reserve sounded nothing like the story told around Waterloo.

In response to my initial questions about the Mennonite migrations, my grandfather suggested I read Dr. Mabel Dunham’s 1924 novel, The Trail of the Conestoga. This historical romance has had, it turns out, a remarkably long shelf-life. After its initial publication in 1924, with a forward penned by Kitchener-born Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, the book was re-printed six times through to 1979 and was adapted into a wildly successful outdoor musical spectacle during Waterloo’s centennial celebrations in 1952. Without a doubt, The Trail of the Conestoga has been the most popularly re-told history of the region.

In Dunham’s depiction, Samuel Bricker and his brother John’s family leave behind their farms and community in Pennsylvania fifteen years after the American War of Independence. Fearing that the new republican government will not honour Britain’s older promise to allow the Mennonites freedom of conscience and the avoidance of military conscription, the Brickers act on rumours of cheaply available land in Upper Canada. After a six week journey, they drive their covered wagons to the Head of the Lake, where a seemingly respectable Member of Parliament named Robert Heasley sells each of them three hundred acres of the best land in all Upper Canada at the “ridiculously low price of a dollar an acre” (111). Following the Brickers’ success, many more families from Pennsylvania migrate north, purchase titles from Heasley, avail themselves of supplies at Coote’s Paradise, and then brave the treacherous road north to the remote Mennonite settlement on the Heasley Tract.

Just as the fledgling community begins to prosper, Bricker discovers, to his astonishment, that “his deed…isn’t worth the paper it is written on” (154). Heasley, it turns out, is not the sole owner of Block II and all 94,012 acres of that parcel are held under a joint mortgage worth $20,000 American dollars. Owing to their religious principles against indebtedness, the Mennonite pioneers fear the loss of their land and their investments as Heasley struggles to meet his mortgage payments. Meanwhile other, newly-arriving Mennonite settlers change course and purchase land in present-day Markham, which diverts increased settlement from the Block II community and thwarts the very acreage sales that would help enable Heasley to meet his financial obligations.

Though Dunham’s novel is structured around these specific historical details, the narrative concerns itself largely with the moral education of Samuel Bricker. This sudden controversy over proper land title shakes Bricker’s faith and confidence in Britain, for “he could not persuade himself that a man of education, a lawyer, a Member of Parliament, could stoop so low as to defraud an innocent and inoffensive people who came as strangers to a land where justice and equity were said to prevail” (154). Fortunately for Bricker and his community, a kindly colonel named Isaac Brock overhears the matter in York and stops in at the Registry-Office to help the “Mennonite in distress,” explaining that “Mennonites, you know, never take the offensive” (158). Bricker, however, does take offense to Heasley’s duplicity, and he stomps off furiously in the direction of the Head of the Lake intent on a confrontation at Heasley’s large, two-story house.

As Bricker slowly learns to control his temper, however, he emerges as the Mennonite community’s hero. He and another man travel back to Pennsylvania as emissaries to solicit the support of their wealthier kin; after much debate, twenty six wealthy Mennonites from Lancaster County come together to form the German Land Company, which purchases the entire mortgage outright.

At the end of Dunham’s novel, all is set to right by 1805. The $20,000 worth of American silver coins is safely carried over the Allegheny Mountains and across the Niagara River (notably, without guns in this post-World War One version of events). The Mennonites not only retain their lands and usher in a new wave of profitable settlement but actually enlarge their territory considerably by the additional purchase of Block III, or Woolwich Township. Moreover, Bricker’s faith in the British empire is restored. In the closing scene, a British officer arrives at Bricker’s freshly plowed fields to offer compensation and wage payments for the Mennonite horse teams conscripted into non-military service during the War of 1812. Though Bricker reiterates the Mennonites’ doctrine of nonviolence, their conversation is amiable and their handshake, in advance of dining together, cements a mutually supportive friendship between the Mennonite and British loyalists in Upper Canada. As for Heasley, the officer is forced to admit that he is simply one of the few “wicked that flourish” (339); that is, Heasley’s wickedness, though repugnant, can be safely ignored.

I moved to the Head of the Lake with my wife, Colleen, in September 2009—except that I didn’t immediately realize that this was where I had landed. I thought we were simply moving to Hamilton so that I could attend McMaster University. Beaconed, like my ancestors of old, by cheap habitation, we ended up renting a small house near the top of the Burlington Heights, across from Dundurn Castle. The historic mansion sits to the east of an old canal cut, which joins Lake Ontario’s waters to the town of Dundas through the marsh of Cootes’ Paradise. On our first walk out along York Boulevard to the Heights, we came to a lookout that offered both a distant view of the Burlington Bay Skyway and a close-up look at a weathered historical placard. Before explaining the history of the canal, the bridge, or Dundurn Castle, the sign established this fact:

The arrival of merchant and trader, Richard Beasley in the early 1770s made the Heights one of the earliest locations for European settlement.

Richard Beasley, Robert Heasley; Robert Heasley, Richard Beasley. The pseudonym is as clever as it is obvious. And the personal implications were even more apparent.

Inadvertently, I had just moved to the very place from which my ancestors in Waterloo had first purchased title to their land. Before the earliest Mennonites had turned north-west, travelling another week to their timbered plots on the Upper Grand, they had waylaid here, briefly, on the Road to York. The towering willow tree in my backyard seemed suddenly imbued with a greater sense of draping majesty; could it have germinated from the seed of a much older willow, itself hanging nearby, offering shade to my distant grandmothers while Beasley flourished his pen indoors with the men?

Of course, the Heights have been heavily over-run since then, and much has changed. During the War of 1812, the British army and local militias marshaled their forces here for several weeks, preparing to counter-attack the Americans at Stoney Creek; their bunkers still ripple through the cemetery. The Great Western strapped ties and rails across the Heights in the mid-nineteenth century, and its iron bridges continue to arch over the canal’s incision. The housing subdivision was built up after World War One, and Highway 403 was paved along the edge of Cootes Paradise in the 1950s.

I looked about in vain for a material trace, amidst this crowded neighbourhood, of my ancestors’ brief stopover here. A lone hitching post would have done the trick, all the better if at a lean, with a single, rusted loop. I ended my search at the base of the willow tree, hoping. It’s possible. Roots lie deep and seeds hibernate, biding their time, awaiting some sudden, shifting displacement upwards into moist soil and sunlight. History past, sprouting again.

Today, Waterloo and Hamilton are often depicted antithetically, as if they are worlds apart. Waterloo is figured as white-collar and tech-savvy, head office to several insurance conglomerates as well as Research in Motion, makers of the Blackberry; Stephen Hawking was recently in town to theorize with the Perimeter Institute, and the large farmers’ market and Old Order Mennonite sightings offer a pleasant indication of general wholesomeness. Hamilton, on the other hand, gets summed up by the view from automobiles traversing the Skyway—all fiery chimneys and great plumes of carcinogens, a decaying steel-town, apparently, and therefore lamentably, out of sync with the new economic order and the information age. Such a dichotomy does a disservice to our present conceptions of both locations; it masks the industrial base and class-divisions of Kitchener-Waterloo, and it fails to see the transformation of Hamilton into a nexus of health care services and research, or its emergence as a hub of artistic pursuit.

These over-simplifications also ignore deeply embedded regional ties—economic and cultural exchanges that have transformed the landscape in which we live. Early log roads, laid down through the Beverley Swamp, connected people and surplus grain from the Grand’s middle and upper watershed to the settlements at the Head of the Lake, where more than a dozen mill wheels once spun by the propelling force of escarpment-fed river runs. The trade serviced both locations equally well; essential supplies from Dundas and Hamilton were carried back up the road to the growing villages of Preston, Galt, Berlin, and Waterloo, while milled grains and other manufactured goods were shipped out to the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean through the Desjardins Canal.

Two hundred years later, exchange between Waterloo and Hamilton continues, in manifold ways, over the various north-south asphalted veins that bleed into the arching, east-west provincial artery that is King’s Highway 401. A one-week journey has now collapsed, by economic necessity and technological possibility, into a fifty minute car ride.

But peel back the blacktop and fill in the canal-cut and you return to the linkage that is Richard Beasley—the man who is celebrated as the first European settler of Hamilton and the man whose land speculating and surveying directly resulted in the settlement of Block II.

Beasley’s legacy, however, is not equally regarded.

An historical placard at the Brubacher House, a Mennonite homestead-turned-museum at the University of Waterloo, registers Beasley’s land dealings as decidedly criminal, like Dunham’s characterization of the man. Of the Block II tract, the sign states that “Beasley made no initial down payment, and stuck with a six percent annual interest on the principal (which he also did not pay), and a binding stipulation that the tract not be subdivided before paying the full purchase price.” To make matters worse, “In 1800, Beasley illegally (and deceptively) sold over 8000 acres of the mortgaged land” to the first twenty six Pennsylvania German Mennonite immigrant families who were “under the false assumption of gaining clear land titles.”

Tour guides at Dundurn Castle, on the other hand, proudly display a wall of bricks from Beasley’s original house, the foundation of which was later incorporated into the construction of the mansion. And while hunting for Beasley through the yellowing card-file index in the Local Archives and History section of the Hamilton Public Library, I came across Nicholas Leblovic’s address to the Head-of-the-Lake Historical Society. In this 1965 speech, Leblovic offers greater context to Beasley’s life, nuancing the financial and political pressures under which he operated. He suggests that Beasley was simply a rather inept businessman, one who was luckily saved from debtor’s prison by the timely German Land Company purchase of Block II (Leblovic 5, 8).

Beyond the debate over Beasley, what both the basement placard at the Brubacher House and this archived historical society proceeding do tell us, which Dunham’s own much more public and oft-retold narrative does not, is exactly to whom Beasley’s mortgage was owed in the first place. And it was owed, of course, to the Six Nations of the Grand River.

How scant and selective is our public memory of this river-place. In elementary school I was fascinated by the “ancient” North American Indians, some of whom, I understood, built longhouses, while others lived in teepees. The differences, by my recollection, seemed to end there. I was always jealous to read of other children, somewhere else, finding arrowheads in their uncle’s field; this, seemingly, didn’t happen in Elmira, though I kept an eye out just in case. Once, while my brother and I helped my dad dig out a new brick patio, we came across a few stalks of corn. I was disappointed to learn that we weren’t uncovering an Indian village site, but simply turning soil that had been a farmer’s field fifteen years previous. It was all so banal.

By high school, World History, the World Wars, and World Issues commanded my attention— interesting, important stuff that usually happened elsewhere, “over there.” Occasionally, though, some of these Great Events did involve the nation of Canada, as my teachers would point out proudly at such moments; like, for instance, when we were given our own spot at the League of Nations at the close of World War One. It was one of the first tangible signals that Canada had entered, finally, the world stage some fifty years after Confederation. But of my specific locale, the world seemed to have passed it by, in ancient times as in the modern now.

It’s an unfortunate myth, this assumption that the land we walk, the roads we drive, the food we eat contain no history, or at least only a faint connection to anything of greater import. It’s the same kind of disconnectedness that allowed my classmates and I to study longhouse Indians, recreating village settings with popsicle sticks and birch bark, like we did pirate ships and pyramids, without making the absolutely crucial connection to the People of the Longhouse, who continue to live downstream.

A triangulation of places that form a larger place. And yet Waterloo Region, the City of Hamilton, and the Six Nations Reserve are not equally connected nor remembered in our public consciousness. It’s a region divided against itself despite the river that connects. For all the loyalist histories of settlement in Upper Canada, all the pioneer villages depicting settler life-ways and their attendant struggles, the history of the Six Nations’ own arrival and settlement along the Grand River is consistently disregarded, if not effaced entirely. This is especially peculiar, I am beginning to realize, given that their existence on the Grand centers not on a claim to ancient territorial inhabitation, like most other Indigenous land claims, but originates from the basis of rights and legalities contained within a Royal Proclamation (1784) and a British land patent (1793). Their legal and historical basis is, in other words, the same as Canada’s legal and historical basis—to ignore the legitimacy of one makes a mockery of the other. And the evidence of our stories notwithstanding, the Six Nations have coexisted alongside both early settlers and contemporary Ontarians for the entire history of this British-Canadian province.

To be sure, the Six Nations have always been acutely aware of the existence of white settlers around them and the expansion of Canadian society along the river. The many letters of Joseph Brant attest to this fact, written as they were from his position as a junior Chief of the Confederacy, as a veteran British Army Officer, and as power of attorney for the Six Nations of the Grand River. Last winter I began to read these letters and papers in The Valley of the Six Nations, Charles Johnston’s invaluable compilation of historical documents pertaining to the settlement of the Grand River. The content of these papers, as well as emerging scholarship, detail the Six Nations’ two-centuries-long struggle to retain autonomy and territorial sovereignty in the aftermath of the American War of Independence.

These voices, and the stories they tell, offer a corrective to the established narrative of this region’s history; they re-draw certain lines of connection and provide, in the process, a richer context to what the present-day struggle at Caledonia signifies. And, for that matter, what the silence of our government bodies signifies, too.

Before European contact and their eventual relocation to British Canada, the Six Nations inhabited an ancestral territory that stretched across what is today upstate New York from the Hudson River Valley through the Finger Lakes district to the Great Lakes region. Sometime about the twelfth century, the warring Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk nations united to form the Iroquois Confederacy, calling themselves the Haudenosaunee meaning “we build the house (together)” (Monture 3, 17). By the beginning of the colonial era, the Haudenosaunee (pronounced ho dee no SHAW nee) were well-positioned, geographically and politically, to benefit from the emergence of the fur and crops trade in the sixteenth century with the French to their north and the Dutch and British colonies to the east of the Appalachian mountains.

In order to preserve these mutually beneficial trading relationships, the Confederacy exchanged the Two Row Wampum belt, a physical and philosophical agreement, with the Dutch in 1613 and then with the English (Monture 24). This white-beaded wampum belt contained two parallel lines of purple beads, which represent the Haudenosaunee canoe and the European sailing vessel. The two boats, each containing its nation’s language, culture, and traditions, coexist peacefully and equally on a shared waterway, even as they maintain their differences.

By the enactment of this peace agreement and as key allies and trading partners with the British, the Iroquois Confederacy wielded considerable political and military influence with both colonial powers and other neighbouring Indigenous nations through the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Despite all that has transpired over the last four hundred years, the Two Row agreement continues to form the “philosophical foundation,” according to Mohawk scholar Rick Monture, by which “the Haudenosaunee have conducted themselves politically in relation to Europeans ever since” (23). And it was this same agreement that the Six Nations sought to re-establish along the Grand River following the loss of their territory.

Caught between the opposing British and American armies, the Six Nations fractured over their differing strategies of involvement in the conflict. While some groups of the Six Nations attempted to assert their neutrality and others fought alongside the American rebels, the majority chose to take up arms in Britain’s defense. Britain’s colonial governors, in turn, promised that Haudenosaunee property and rights would be fully protected and restored to them ( Johnston xxxiii).

As the war progressed and the tide began to turn on the British, the Haudenosaunee became increasingly anxious about their precarious position, especially following American General Andrew Sullivan’s 1779 scorched earth campaign through the Finger Lakes, which laid waste to many of the Confederacy’s fields, villages, and storehouses. Despite continuously affirming their earlier promises, the British, at the end of the Revolutionary War, surrendered Haudenosaunee territory to the Americans and withdrew into the province of Quebec (xxxiv). The Iroquois Confederacy, divided already by the fighting, found themselves dispossessed at Buffalo Creek and Niagara or clinging to fragments of land in New York.

When Sir Frederick Haldimand, Governor of Quebec, learned about these “serious omissions” from the Treaty of Paris, he moved quickly to appease Haudenosaunee anger by suggesting the Grand River Valley as a possible site for relocation. Brant and other Chiefs of the Six Nations agreed, so Haldimand secured the valley’s purchase from the Missisauga-Ojibwe nation at the Credit River and proclaimed this tract to be the Six Nations’ territory in perpetuity. In 1784, the largest remnant of the Haudenosaunee, consisting of some 2000 people, moved west from Buffalo and settled by nation along the Grand, from the Tuscarora site at Lake Erie up to the Mohawk village that took the name of Brant’s Ford (xxxv-xl).

The Six Nations’ struggle to re-establish themselves was compounded, however, by a number of issues. Due to numerous casualties throughout the war, the Six Nations of the Grand River consisted of a large number of widows and children. In 1788, according to one of Brant’s biographers, a large famine wiped out the region’s crops and left the Six Nations even worse off than their white neighbours (Kelsay 553-54). Their food supply became steadily worse over the course of that first decade. Readily available game meat began to vanish as ever-greater numbers of United Empire Loyalists moved into Upper Canada and began clearing the forested land on either side of the Haldimand Tract, whether throughout the Niagara Peninsula or in Oxford County along the Thames River. As a result, individuals from the Six Nations of the Grand River began to migrate out to other Haudenosaunee land holdings in Canada and the United States.

In order to stem the loss of their people, Brant and the re-established Confederacy Council of the Six Nations of the Grand River decided to sell certain portions of the Haldimand Tract. The plan, according to Brant’s power of attorney document, was that “the monies arising out of the Sales thereof may be laid out and Converted to the purchasing an Annuity or Stipend for the future support of themselves and their posterity” ( Johnston 79-81).

In 1791, with the encouragement of their neighbours, the Six Nations of the Grand River enlisted Augustus Jones, a government surveyor, to conduct the first official land survey of the Tract. This survey, unfortunately for the Six Nations, located the headwaters far beyond the land that Haldimand had actually purchased from the Missisaugas. More disappointing yet, the colonial government was not forthcoming with a deed in fee simple for the Haldimand Tract, preventing the Confederacy from selling portions of the land for seven years.

Most of Brant’s correspondence in the intervening time relays the Six Nations’ dissatisfaction with their increasingly dependent status on the British; one letter from Brant on December 10, 1798 is particularly telling and worth citing at length:

Sir, I presume that you are well acquainted with the long difficulties we had concerning the lands on this river—these difficulties we had not the least idea of when we first settled here, looking on them as granted us to be indisputably our own, otherwise we would never have accepted the lands, yet afterwards it seemed a little odd to us that the writings of Gov. Haldimand gave us after our settling on the lands, was not so compleat [sic] as the strong assurances and promises he had made us at first, but this made no great impression on our minds, still confiding in the goodness of his Majesty’s intentions…. Unhappily for us we have been acquainted too late with the first real intentions of Ministry; that is, that they never intended us to have it in our power to alienate any part of the lands; and here we have been prohibited from taking tenants on them, it having been represented as inconsistent for us, being but King’s allies, to have King’s subjects as tenants, consequently I suppose their real meaning was, we should in a manner be but tenants ourselves, as for me I see no difference in it any farther than that we are as yet rent free…. (Brant 13-14)

There are, in this letter, a number of unfortunate, though revealing, historical ironies playing out. While the Six Nations leadership presently regrets having sold any of its territory and is currently fighting for lands taken but not paid for, the Canadian government insists that the Six Nations of the Grand River have always been subjects of the British Crown, not its national allies. At the juncture of this letter, however, the argument was reversed, with the colonial government maintaining that the Confederacy Council could not sell portions of its land because this would result in the jurisdictional trouble of having British subjects inhabiting the territory of a national ally. In this respect, Brant was quite right to note that if the Six Nations of the Grand River did not have the power to alienate any part of their lands, then they were as good as tenant-subjects of the British anyway; this is to say that gaining the authority to sell their land was also an assertion of sovereignty.

Yet, in order to gain that authority, the Six Nations had to agree to conduct their sales and invest their earnings through the auspices of the Department of Indian Affairs. Doing so meant depending upon the advice and fiscal management of a committee of British politicians and lawyers who were called the Trustees of the Six Nations. With approval in place, in the winter of 1798, Brant and the Confederacy went ahead and put six blocks of land up for sale, finding an immediate purchaser for Block Two in Brant’s acquaintance, Richard Beasley, from the Head of the Lake.

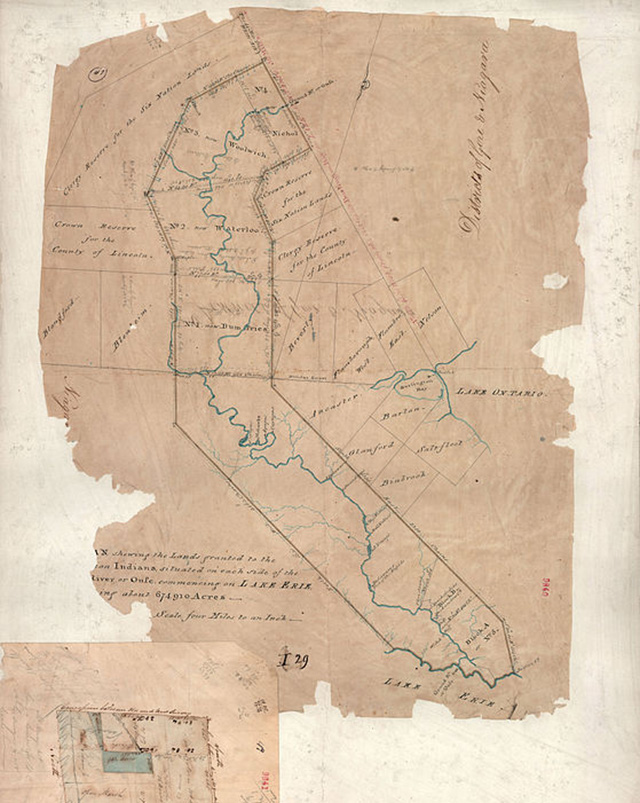

I had stumbled upon a triangle of trails that led me down paths I had not known existed. In my initial hunt for my Mennonite history, I encountered, via Beasley and the history of his land dealings, an old map of the Head of the Lake. It was hand-drawn in 1793, copied in 1909, and laminated sometime after for its protection. Here on this map, the black-top is, in fact, peeled back, and the canal cut through the Burlington Heights is still some fifty years off. In place of the present city of Hamilton is a convergence of trails that connect the scattered points of human interest in Upper Canada at the time. Along the south shore of Lake Ontario meanders a route toward Niagara, an early etching of King Street and the trail that all settlers, whether Haudenosaunee, British, or Pennsylvania Dutch, took in settling the Niagara Peninsula. At the western tip of Burlington Bay, a “Carrying Place” marks the beginning point on a long “Path to the Mohawk Village Grand River and Detroit,” which climbs the escarpment and journeys southwest off the map. From the “Landing Place” at Coote’s Paradise, a “Road to Hunting Ground on Grand River” follows the curve of the escarpment wall and then veers northwest into the wilderness of the upper watershed.

This triangulation of the Mohawk village, the northern hunting grounds, and the British fort at Niagara does more than delineate early routes of movement and migration that criss-crossed at the Head of the Lake; it implies crucial interrelations and mutual dependencies between the Six Nations of the Grand River, the British colonial government, and the Mennonite and Loyalist settlers at the turn of the nineteenth century—interrelations and dependencies now forgotten, ignored, or scorned. And in many ways, our present detachment makes sense; who wants to talk about, or dwell upon, the history and legitimacy of the two-hundred-year-old land transactions that underlie the infrastructure of this valley?

Especially when it’s a history as muddied as the southern Grand’s effluent-filled waters.

As the six, crown-managed block-sales became mired in their own financial difficulties, the middle and southern sections of the Six Nations’ tract were quickly and unduly carved up by arriving settlers, squatters, and speculators. Against these emergent improprieties of land settlement, the Confederacy Council drafted resolutions to their trustees at Indian Affairs, disputing specific irregularities of ownership on their territory. One of thirteen such claims filed in 1809 cites 4800 acres that were apparently marked out for Jones, the very man who conducted their land survey ( Johnston 110-12). Rather than deal with the infringements of its settler-citizens, the government turned such improprieties into further reason for the Six Nations to alienate greater portions of their land.

Where money was in fact paid out to the Trustees, as in the case of Blocks Two and Three for example, much of the funds were subsequently lost, ill-invested, or pilfered for development projects that attracted yet more settlers onto the tract. Between 1832 and 1861, for instance, the Trustees of the Six Nations made ever-increasing capital investments in the Grand River Navigation Company after the colony’s business elite refused to bear further risk. In this way, Six Nations funds were used to appropriate their own lands and natural resources in the process of structurally altering the lower Grand to permit barge traffic on the waterway (Hill 40). While the company “had opened up the middle and lower Grand River Valley…foster[ing] towns and cities…and townsman, farmer and merchant had benefited,” the Six Nations, who were eighty percent shareholders by the time of bankruptcy, had never been granted representation on the Board of Directors and were “never paid any dividends” (38-40). In other instances, their land was flooded for the construction of the Welland Canal, cut through for the passage of railways, and leased for the building of roadways, such as the Hamilton-Port Dover Plank Road—now the focal point of the stand-off in Caledonia.

By 1850, less than 5% of the original Haldimand Tract remained in possession of the Six Nations of the Grand River.

Objections over the loss of this territory and the mismanagement of Six Nations funds did not only come from the Confederacy Council. Lord Durham, too, in his influential report on Upper and Lower Canada following the 1837 rebellions, was unequivocal in his condemnation of the colonial authorities’ trusteeship of the Six Nations’ lands, saying:

To the extent of this alienation the object[ive]s of the original grant, so far as the advantage of the Indians was concerned, would appear to have been frustrated, by the same authority, and almost by the same individuals that made the grant. I have noticed this subject here for the purpose of showing that the government of the colony was not more careful in its capacity of trustee of these lands, than it was in its general administration of the lands of the Province. (Johnston 298-99)

This double standard between the careful administration of the rest of the province and the hapless, near-profiteering, administration of the Haldimand Tract has left a dubious and even illegitimate substructure beneath the human environment along the Grand River.

This deeper territorial history seems surprisingly new to most of us settlers in this valley because we have consistently avoided these details in the stories we tell. And by avoiding for so long, we have forgotten. That being said, our forgetfulness and inattention have a history, and it’s a relatively recent phenomenon.

In Dunham’s opening page, beside her dedication to the memory of her mother and her mother’s people, she acknowledges her indebtedness to Ezra E. Eby’s tome, A Biographical History of Waterloo Township. This dependency is not surprising given that Eby’s 1895 text is one of the earliest recorded accounts of the Mennonite settlement on Block Two. What is surprising, however, is that in contrast to the complete absence of the Six Nations from Dunham’s story, Eby offers us the traces of a slightly more integrated and co-dependent relationship between the Mennonites and the Six Nations of the Grand River.

Speaking of the town of Berlin in the years following the War of 1812, Eby notes that “in those times the Indians were very numerous” (10.3). Eby mildly objects to the common stereotype of the ‘savage Indian,’ stating instead that “if kindly treated [they] would never injure any one” (10.3); this phrase, though, is a strange insertion because nowhere else does he allude to any potential violence, kindly treated or not. In fact, Eby records that “parents often left their children alone and the Indian children would play with them and the squaws [sic] would take care of the white children” (10.3-11.1). Evidently, the two communities lived in close contact for “as a rule the young people were always rejoiced to see the Indians come” (11.1).

Eby also describes an ongoing system of exchange, where “for a small loaf of bread and a six-penny crock of thick milk the Indians would bring them the nicest quarter of venison or a large basket well filled with the finest of speckled trout” (10.3). More than simply economic trading partners, Eby suggests that “often during cold nights when the inmates of the house had retired to their respective places of rest, their kitchen would be taken possession of by the Indians who would spend the night sleeping warm and comfortable around the large fire place” (11.1). Of course, the pastoral nostalgia of these descriptions makes their accuracy somewhat suspect; that being said, Eby’s account at least recognizes relations between the Mennonites and Six Nations, whereas Dunham erases them.

A decade after Dunham’s novel was published, a local historian named I.C. Bricker, himself a descendent of Samuel Bricker, wrote an influential article in 1934 for the Waterloo Historical Society. Bricker opens with an exclamation that in Waterloo “were performed deeds of unsurpassing interest; here were achieved great things; here occurred an event of national importance—the coming of the Mennonites” (81).

Bricker offers “a fleeting outline of the preceding period,” where he acknowledges the river passageways used by the Algonquin, the Huron, and the Neutral Indians. He then cites the Haldimand proclamation that granted the Grand River territory to the Six Nations (81). He correctly details how Joseph Brant, through the power invested in him by the Six Nations Confederacy, surrendered “certain portions of this land to the Government that it might be sold and the proceeds invested for the benefit of the Indians” (82). However, by the act of signing over land title, the Six Nations are suddenly banished to the disappearing past.

In Bricker’s account, the Six Nations of the Grand River had made inadequate use of the region’s fertile soils, for “this forest primeval was but the happy hunting ground of a few roving bands of Redman. Here and there in some rich meadow opened to the sun, the Indian squaws [sic] would cultivate, with their crude stone implements, the black soil and sow their scanty stores of corn and beans” (83). Though he has already established the initial, legal transaction of the land sale to Beasley, Bricker still, interestingly, feels the need to assert the Six Nations’ seemingly insignificant use of their land. It’s the same argument levied today whenever Indigenous land tenure stands between capital investment and ‘untapped’ natural resources.

By employing the myth of ‘Indian’ indolence, Bricker justifies passing over the Six Nations’ continuing existence along the Grand, and instead he ushers “our Canadian progenitors” onto the vacated land (86). Fusing both biblical typology and British-Canadian loyalism, Bricker declares that “for twenty and more years they, like the Israelites of old, had been crying unto Him for some Promised Land where that freedom and peace which they had previously enjoyed under the British flag, could again be realized” (86).

A promised land where freedom and peace could again be realized. It’s a yearning so simple, perhaps even universal, yet so frequently frustrated. It’s a yearning often frustrated by the yearnings of others. The discrepancy I trace out above—Eby’s romanticism versus Dunham’s absences and Bricker’s avoidance—is not coincidental. While Eby could, in the tenor of the late-Victorian era, wax nostalgic about the ‘disappearing Indian,’ by Dunham and Bricker’s time, the Six Nations of the Grand River had clearly not disappeared. And they weren’t going to. But rather than having to account for the continuing existence of the Six Nations of the Grand River, Dunham and Bricker simply pass over Eby’s descriptions of Haudenosaunee-Mennonite relations, despite their otherwise heavy indebtedness to his text.

Three years before my grandfather was born and in the same year that Dunham was writing her novel, the Six Nations of the Grand River were causing considerable embarrassment to the young nation of Canada on the international stage. Deskaheh, a Cayuga Chief and spokesman of the Six Nations of the Grand River, had travelled on a diplomatic mission to Geneva in 1923 to elicit the support of the newly-formed League of Nations. He sought international arbitration for the Six Nations’ significant political and financial disputes with the Canadian Government.

Declaring the Six Nations to be the original League of Nations, Deskaheh conveyed the confederacy’s claim to be “an organized and self-governing people” (qtd. in Rostkowski 436-8). In his appeal to individual member-nations, Deskaheh called attention to the Confederacy’s historical, national alliances with the Dutch in the Hudson River valley and later with the British, giving specific mention to the Haldimand Proclamation; both European nations, he noted, “recognized us as a confederacy of independent states” (qtd. on 438).

Deskaheh then laid out four major complaints against the Government of Canada. He cited, first, the Enfranchisement Act of 1919 as an imposition of “Dominion rule upon neighbouring Redmen.” He protested the armed invasion of the reserve by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in 1922, which enforced Canadian penal codes on Haudenosaunee territory. He called attention to the large sums of mis-appropriated money from the Six Nations’ Fund, and he objected to the efforts of the Federal Government to weaken the political strength of the centuries-old Confederacy Council by attempting to institute a new Band Council, whose power would rest within the Department of Indian Affairs (442).

Deskaheh’s appeal gained the initial support from the Netherlands, their original European ally and a key player in Geneva, as well as from Estonia, Ireland, Panama, and Persia. However, the Canadian Government, with the assistance of Britain, reacted strongly and defensively, forcing those member-states who were tentatively supporting the Six Nations to desist entirely. For Joelle Rostkowski, a French scholar of the Americas, the actions of the League with respect to the Six Nations’ petition demonstrated that it was “first and foremost, an exclusive and protective ‘club of Nations’” (439).

After silencing Deskaheh’s international petition, the Government of Canada acted swiftly on matters pertaining to the Grand River Territory. It instituted the Band Council in September, 1924, deposing the Confederacy Council and exiling Deskaheh from the reserve for his trouble-making; he died in New York shortly thereafter (451-2). In 1927, the Federal Government reformed the Indian Act and made it illegal for all First Nations to hire legal representation for any land claims suit against the federal government.

Though these provisions were repealed from the Act in 1951, the legacy of discriminatory avenues to land claims resolutions in Canada persists into the present, with the government continuing to serve as negotiator, defendant, judge, and jury. In the 1970s, for example, the Band Council created the Six Nations Lands Claims Research Office and, by 1994, had submitted twenty-seven land claims with the Crown. While these claims were all duly received by the Office of Native Claims, only one, in 1980, was fully resolved. Though four other claims were validated for negotiation, they were closed in 1995, along with the twenty-five additional, unopened claims, by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (Coleman). One of those unopened claims, which was filed on June 18, 1987, concerned the Hamilton-Port Dover Plank Road in Caledonia.

As one politician put it mildly in the 1924 federal report, which ironically also called for the establishment of the Band Council, these constant frustrations of ‘Indian’ grievances “shakes their confidence in British justice” (Rostkowski 451).

I unstitched the Canadian flag from my backpack. I don’t mean to seem ungrateful; certainly, the maple leaf patch has served me very well through numerous backpacking trips. In England, where my friend and I weren’t even trying to hitchhike, an older man still pulled over for us; “my son lives in Toronto,” he explained as we climbed in. Out on the prairies, that summer of 2006, when I actually was trying to hitchhike, several truck drivers hauled their rigs to the shoulder of the Trans-Canada Highway and shouted, through the settling dust and diesel exhaust, “you weren’t a drunk Indian, so I had to stop for you!” I was thankful for these rides, but equally conscious of the terms under which they were offered.

White privilege. Let’s name it for what it is. In the angered reactions to the land claim dispute at Caledonia, one particularly vocal contingent of white Canadians have protested what they see as “two-tier justice” at work; after a failed attempt to enforce a court order to remove the so-called illegal occupiers, the police allowed the standoff to continue, eventually turning their barricade around to hold off the residents of the town. Now that the Ontario government has bought out the developers and is holding the tract in trust, these same people continue to gather for “anti-racism” rallies, where they argue that the white residents of Caledonia have been subjected to racism and terrorism from the Haudenosaunee.

I’m a reluctant activist, which I owe to the conservatism of my roots, and confrontation makes me extremely uneasy. Still, this reverse-racism logic is a cruel parody of the history and struggle that has structured the human habitation of this river valley. When I heard of people from Hamilton, Toronto, and Kitchener gathering in Caledonia in the spring of 2010 to protest one of these ‘anti-racism’ rallies, I joined. But I needed my backpack to carry my notebook and camera.

In the context of Caledonia, the emblem of the maple leaf takes on new meaning for me. In February 2010, Sidney Crosby scored an overtime goal that caused the entire nation to erupt in a deluge of red and white; in Caledonia on a frigid afternoon one month later, residents of the town and other Ontarians unfurled the same flag, tied it to hockey sticks, and hoisted it high. A national battle in two parts, I suppose. But this second battle is considerably more ugly, more drawn-out, more pernicious than a game of hockey. This flag waving—which billowed angrily at Oka, at Ipperwash, and again at Caledonia—is it Canada showing its true imperial colours? Or are these flag bearers simply appropriating a national symbol and flapping it for their own ends? I suspect it’s a little of both, but either way, it makes me wary.

Does it make a difference, though, that my version of Canada can co-exist with and learn from the Haudenosaunee? That I believe something productive and collective could be gained by the communities of the Grand River Valley seeking out reconciliation with each other? That I think we need to begin listening generously to each other’s stories, widening the scope of our own understanding, and seeking out a deeper inclusivity with respect to the complex history of this place?

This is why I am also troubled by the characterization, made by some of my fellow-protestors that day, that Caledonia is, essentially, “a racist, little town.” No doubt, the hatred and animosity directed by some of the residents toward the Six Nations has been blatantly racist. And we should call a spade a spade. But unmentioned in such a blanket statement are the efforts of other residents to form organizations that work to bridge differences and promote understanding. The statement also suggests a degree of urban and intellectual self-righteousness. But more importantly, this rhetoric plays into the Six Nations vs. Caledonia divide, entrenching a binary that our political and economic professionals in Toronto and Ottawa have been only too willing to let stand and detract attention. Quietly, the Ontario government bought out the developer and paid out area businesses in an effort to ‘redress’ their lost profits; now Queen’s Park and its courts sit mum, refusing to even address, let alone redress, the core claim at stake. In an attempt to maintain business-as-usual throughout the rest of the province, the government is clearly buying silence, to the detriment of both the Six Nations of the Grand River and the residents of Caledonia. So while the anger of some in the town is misplaced, the town does have cause to be angry.

This present that we inhabit now is the result of an accumulation of past events, decisions, and movements. Which is another way of saying that the past is not past. As the legacy—and seeming pastness— of land transactions along the Grand River resurface forcefully into our present, we are, collectively, being compelled to reexamine the history of this place.

It’s both a daunting challenge and a tremendous opportunity.

For the moment, however, Ontario’s courts are unwilling to consider this challenge; in (not) doing so, they do a disservice to us all, for their silence reinforces the myth that First Nations’ land claims in Southern Ontario are presumptuous, are utterly preposterous. But there is grievance here, grievance that grows more legitimate the longer Ontario refuses to address it. In contrast, argues Christopher Moore, a Toronto-based writer and historian, the courts of British Columbia have done a much better job over the last forty years of decision-making and land claims rulings of “gradually acclimatizing both the government and the citizenry to the idea that aboriginal title could not be avoided” (Moore). The power of this cultural and political education is such that Moore tracks a growing appreciation for the new power-sharing model that is underwriting—not harming—much economic development and community cooperation in British Columbia.

If Ontario’s courts will, sooner or later, be forced to address the complexities of these land claims, then what also cannot be avoided is our collective need to re-make the stories we’ve been telling about this place. This isn’t simply a matter of settling past injustices and moving on, like a quick, governmental apology; it is, more fundamentally, a matter of re-imagining how we might mutually and cooperatively inhabit the land along this river.

I feel, sometimes, a long way off from my great grandmother’s burial place. That long, reverberating echo of earth thudding on wood followed me out past the field of corn beyond the cemetery; it trailed me down through the wooded ravine, and it waded out with me into the Grand River. The current, pulling south from West Montrose, is gentle, worth riding, but it’s still more than I bargained for. Voices call out from the banks of each twist in the river run; they commingle with the flotsam of two hundred years of settlement; they give substance and meanings to the ringing musicality of that earth-thumping echo.

My earlier conception of this place has come undone by these reverberations. My own storyline-stitching has come loose. This is because local history, like the local river, is never entirely local. Inevitably, localized stories intersect with other stories. These branch narratives spill forth into the same waters, churning together downriver with a vehemence of emotion, submerging deposits, surfacing contaminants. We’ve been content to watch these thickened waters wash out, through our continental drain, eastwards to the Atlantic Ocean; we’ve been content to hope that the waters of the greater watershed will dilute the potency of meanings from this particular river-place. But these waters evaporate, west-winds blow, and rain consistently returns the Grand River’s waters back unto itself—water that refuses to escape our inattention.

Geoff Martin holds an MA in Literature from McMaster University and grew up in the Waterloo Region. He currently writes and teaches in Chicago.

Works Cited

- Brant, Joseph. “Letter (Grand River, Dec. 10, 1798).” In An Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English. 3rd edition. Eds Daniel David Moses & Terrie Goldie. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2005. 13-14. Print.

- Bricker, I.C. “The History of Waterloo Township up to 1825.” Waterloo Historical Society Annual Reports. 1933-34. 81-131. Print.

- Coleman, Daniel. “Broken Pine.” In Hamilton Arts & Letters. Issue 3.1. Spring 2010. Electronic. Dunham, Mabel. The Trail of the Conestoga (1926). McClelland & Stewart: Toronto, 1979. Print.

- Eby, Ezra E. A Biographical History of Waterloo Township…Being a History of the Early Settlers and Their Descendants, Mostly All of Pennsylvania Dutch Origin (1895). Ed. Eldon D. Weber. Kitchener, ON, 1971. Print.

- Hill, B.E. “The Grand River Navigation Company and the Six Nations Indians.” In Ontario History. 1971. Print.

- Johnston, Charles M. “Introduction.” The Valley of the Six Nations: A Collection of Documents on the Indian Lands of the Grand River. Toronto: The Champlain Society for the Government of Ontario, 1964. xxvii- xcvi. Print.

- Kelsay, Isabel Thomposn. Joseph Brant 1743-1807: Man of Two Worlds. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University, 1984. Print.

- Leblovic, Nicholas. “The Life and History of Richard Beasley, Esquire.” In Wentworth Bygones: Head of the Lake Historical Society. Vol. 7. 1967. 3-16. Print.

- Monture, Rick. Teionkwakhashion Tsi Niionkwariho:ten “We Share Our Matters”: A Literary History of Six Nations of the Grand River. Thesis, McMaster University, May 2010.

- Rostkowski, Joelle. “The Redman’s Appeal for Justice: Deskaheh and the League of Nations.” In Indians and Europe: an Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays. Ed. Christian F. Feest. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989. 435-453. Print.