Launched: Fast Commute by Laurie D. Graham

By Laura Rock Gaughan

Laurie D. Graham grew up in Treaty 6 territory (Sherwood Park, Alberta). She currently lives in Nogojiwanong, in the territory of the Mississauga Anishinaabeg (Peterborough, Ontario), where she is a writer, an editor, and the publisher of Brick magazine. Her first book, Rove, was shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award for best first book of poetry in Canada. Her second book, Settler Education, was a finalist for Ontario’s Trillium Award for Poetry. Her poetry has been shortlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize, won the Thomas Morton Poetry Prize, and appeared in the Best Canadian Poetry anthology. Laurie’s maternal family comes from around Derwent, Alberta, by way of Ukraine and Poland, and her paternal family comes from around Semans, Saskatchewan, by way of Northern Ireland and Scotland. She has about a century of history in Canada.

Q: Fast Commute illuminates levels of responsibility and implication—for the land, the landscape, the toll of humans at scale, but also for an individual life. How a person not of this continent can claim a home, a connection, and history on this land. The names of places and species. How did you approach such varied elements and connect them? As a matter of craft, how do you decide what weight each element will get? Was it many drafts, trial and error, or something else?

It all arrived in pieces, chunks, a few words/lines/images at a time in some cases, or a page or two at a time, and it took me a while to realize that all these pieces were organizing themselves into a larger thing, a book-length poem. Parts of this even started out in point form, so I knew early on that this book was trying to show something big, taking on attributes of the list poem, saying as much as it can about its (already quite large) subject.

Organization on the level of the line or the stanza felt almost arbitrary, or like the simple piling up of detail would yield the result I wanted more than the specific order it all came in, though there are lines and images that to my ear do belong close to one another, and there are pages that do lean toward existing more discretely on their own. But I moved things every which way when I was editing; it all felt pretty malleable, and at times too malleable, like I lacked firm ground to stand on, which is sort of what the book’s about—or rather, it’s not the ground’s problem but my understanding of it that’s lacking.

But two things did in the end guide how I organized the book: first, connecting the colossal ongoing “growth” in southern Ontario to the settlement of the West felt important. The poem starts on the prairies, at the moment after the Northwest Resistance, after Batoche and the sham trials and the hangings, with settlers and homesteaders creating towns and industries, and at its most basic level the book is arguing that nothing much has changed. And second, the overall shape of the piece—from disconnection to first gestures toward relation, from speeding over the river on a train to sitting down beside it and watching and listening to it—felt like the move I most wanted the book to make.

Q: This long poem has a you and an I. Are they multiple speakers or a single speaker with different angles of approach? The posters referenced, with their advertising slogans, also seem to function as speakers from the past. Can you talk about this fluidity of perspective?

That wasn’t intentional, that shifting perspective, but I think it results in a thing more slippery and hence more broad and perhaps more true to life or able to take up more of the world. I did puzzle over that one. And consistency of pronouns, keeping it to a neat “I” throughout, was striking me as suspect or false: as I was writing I really was talking both to and about myself, and pointing fingers at people, addressing the perpetrators. Not worrying about consistency or organization created the potential to take us all up, writer and reader together, draw us into thinking deeply about how non-Indigenous people, and especially white settlers, account for this mass obliteration still being done in their names, and what we have to do, all the frameworks and systems of belief that need to change, in order to stop it.

Q: You document human impact on the land—a catalogue of degradations—in a way that expands our vision. We must see the garbage collecting at the foundation of a new build, the bulldozed berms, the white breadcrumbs scattered by the creek—and I felt that those things, too, hold a kind of beauty in this depiction. Rendering of them in poetry creates fine language out of something ugly, a paradox. What do you think?

This might, in a way, be what Adrienne Rich describes at the end of her poem “What Kind of Times Are These”: “to have you listen at all, it’s necessary / to talk about trees.” My goal with this book is to have the reader pause on that ugliness you mention, that catalogue, its expansiveness and relentlessness, to consider it for long enough to see it as a direct outgrowth of resource extraction and a mode of supremacy that insists on its own presence only and the eradication of all else. To have the reader see well and sit with the profound harm we’re still perpetrating on this continent, it’s perhaps necessary to find the beauty that remains in its contours. And this might then lead to seeing better what life remains there, surviving in spite of, in the midst of, the destruction. An ode to life, even as that life is being decimated.

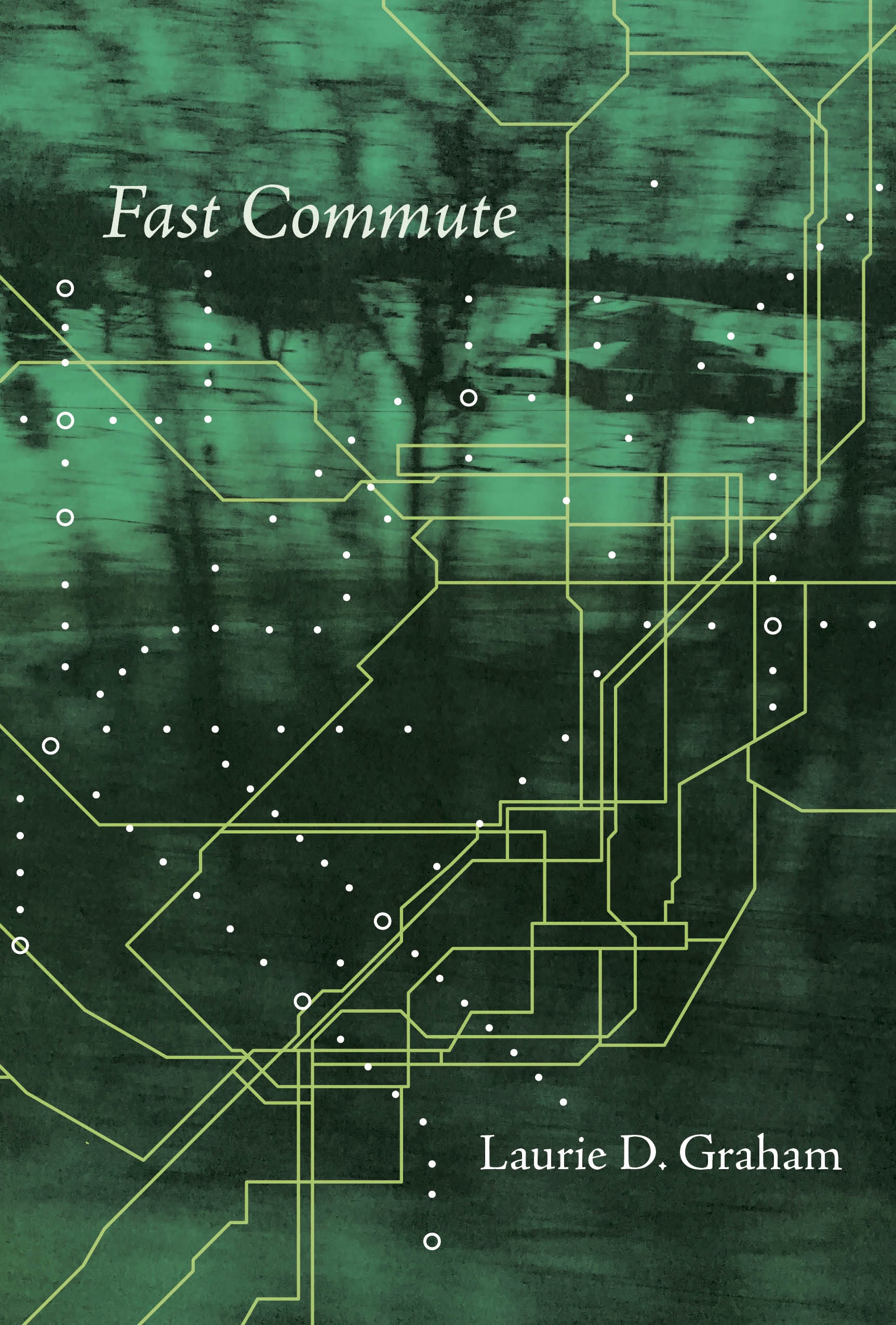

Q: You are credited with the cover image. Tell me about that image and its use in the cover design.

When I was deepest into the writing of this book, I was taking the train between Kitchener and Toronto regularly to go work at the Brick magazine office, and I was snapping lots of photos of all I was whizzing past—holding my phone up to the window and pressing the button a lot, which felt like a kind of research—and when my publisher asked me to send ideas for cover imagery, I sent a selection of those train-window photos, as reference. And Andrew Roberts, the book’s designer, ended up incorporating one of those photos into the design, overlaying a sort of commuter train map on top of it. I love the green Andrew chose as the background colour, and how if you’re looking at the book from far away it just looks like foliage and you can’t make much else out.

A similar thing happened with my last book, Settler Education: I sent some reference photos and they used one as the background image, so now a theme has emerged. I feel it important to stress, however, that I am in no way a photographer!

Q: What are you working on now?

I’ve got most of a draft of the next book of poetry written, and I’m at the point of trying to figure out what’s left for me to do to make the thing a thing; as often happens with me, the writing happens fast, and then I have to sit and figure out what I’ve done, what work the poems are doing together, and whether they’re doing the right things.

I’m also taking tentative steps into prose, of a sort, of a style that’s feeling quite new to me, and which these days I’m kind of test-driving in a biweekly newsletter. I hope something comes of it, but that might take a while. Poetry I can fit into the crannies of my life pretty well, but prose, to me, needs the day, needs all the days, so I’m just trying to figure out how that one fits. I want it to fit. It’s a stretching out that has been feeling good and urgent.

Laura Rock Gaughan’s fiction and essays have appeared in literary journals and anthologies. Her short story collection, Motherish, was published in 2018.