You’re Not a Monster

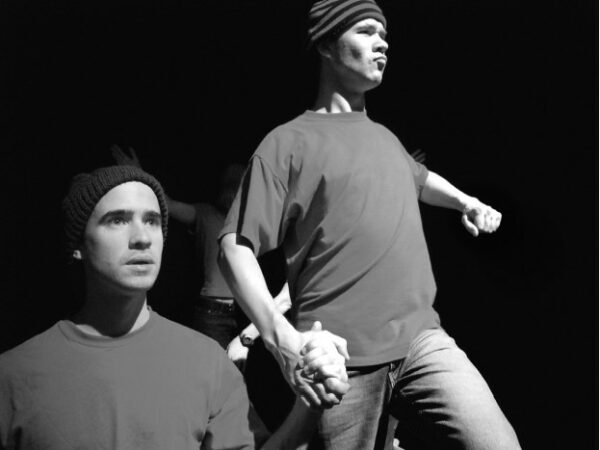

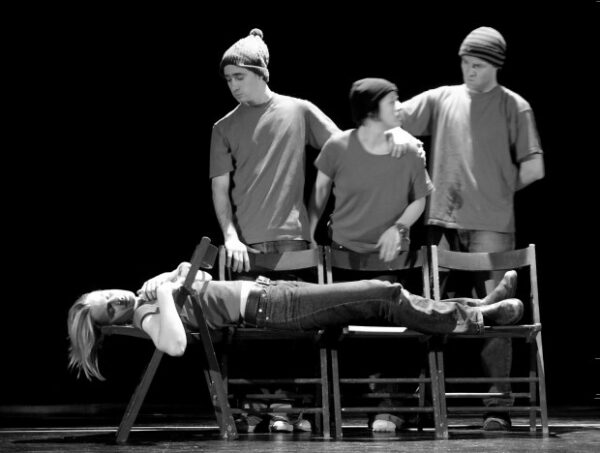

with photographs by John Haney

1.

GaRRy Williams’s copy of Towards a Poor Theatre looks like it has been through the wars. It is a Danish edition, published (in English) by Odin Teatrets Forlag in 1968. The cover, printed on thin, laminated stock, has been chafed to the consistency of lambskin. The binding is flaking off. The glue along the signatures has become a calcareous rind. The text is printed letterpress, in a proletarian sanserif, with a noticeable and uneven emboss.

This book is a collection of the writings (and, in some cases, speeches or interviews) of the Polish theatre director, producer, theorist, and pedagogue Jerzy Grotowski. In 1959, at the age of 26, Grotowski began work with a small, experimental theatre group in the town of Opole. This group would go on to become the Teatr Laboratorium, or Laboratory Theatre, international in its influence and renown. In the texts collected in this book, Grotowski’s signature notion of a “poor theatre” is elaborated and refined. It is a theatre which answers the technical bravura of film and television, not with technology but with actorly technique. It is an actor-centred theatre, and yet a theatre in which the actor gives himself completely—not to the spectator or for the spectator, but, somehow, in his stead. It is a theatre stripped down to its essential elements:

The theatre must recognize its own limitations. If it cannot be richer than the cinema, then let it be poor. If it cannot be as lavish as television, let it be ascetic. If it cannot be a technical attraction, let it renounce all outward technique. Thus we are left with a “holy” actor in a poor theatre.

In the book’s title essay, Williams has marked the following passages, lightly, by means of a pencilled ‘x’:

[For] each production, a new space is designed for the actors and spectators.

[We are concerned with art as] a process in which what is dark in us slowly becomes transparent.

Then I clearly saw that myth was both a primeval situation, and a complex model with an independent existence in the psychology of social groups, inspiring group behavior and tendencies.

What is possible? First, confrontation with myth rather than identification.

If the situation is brutal, if we strip ourselves and touch an extraordinarily intimate layer, exposing it, the life-mask cracks and falls away.

[The actor entrusted to me] must be attentive and confident and free, for our labor is to explore his possibilities to the utmost. His growth is attended by observation, astonishment, and desire to help; my growth is projected onto him, or, rather, is found in him — and our common growth become revelation. This is not instruction of a pupil but utter opening to another person, in which the phenomenon of “shared or double birth” becomes possible.

2.

I first met Williams in my second year at Mount Allison University, where I was studying English and he, English and voice. It quickly became clear to me that he harboured erudition which belied his current status as an undergraduate at a small-town Canadian school. He had been born in Halifax, I discovered, the child of visual- and performance-artists, but the family had moved shortly thereafter to New England. In 1980, his father’s work had brought them to Berlin, where Williams had spent the remainder of his childhood. By the time he arrived at Mount Allison, in 1999, he had already studied at the Free University Berlin and at Manhattanville College, New York, and had taken supplementary theatre courses in Stratford-upon-Avon, London, Williamstown (Massachusetts), Berlin, and Barcelona. How on earth, I wondered, had he fetched up in Sackville, New Brunswick?

The town of Sackville is dear to me. It has been my home on and off for almost eight years now, and I have a rich sense of community and of cultural life here. But the population peaks at 8000 when the school year is in full swing. What might draw a person here from London, Berlin, New York?

Well, for one thing, the fact that the population peaks at 8000. I learned in time that the Old World cosmopolitanism which held such allure for me was a stuffed shirt to Williams. What he was after was New World charm. In a recent, unpublished “Text Montage,” he writes of the Sunday service at a Sackville church with a particularly enthusiastic congregation:

I’d seen these men and women become enthralled in worship, spontaneously sharing a dream they’d had the night before with the congregation, unashamedly intoning songs in arrangements for out of tune guitar, tambourine and Hammond organ, more moving and true than most of the recitals I was to witness at the Conservatory…. I admired their whole-hearted commitment, their utter lack of city slick.

What to me represented a sort of rube-ish credulity, then, to him represented authenticity, a lack of pretense. Williams had given up on his Old World education when he tired of being told he needed to have studied Latin in high school if he wanted to go on to study anything else. I had despaired of my New World education when I found out that my high school didn’t offer Latin classes. Williams was something of a looking-glass creature to me.

I worked with him on various student theatricals during our time at Mount Allison—most notably on an outdoor production of Twelfth Night, which he co-directed with Erin Brubacher. These projects were enough for me to gain a sense that, however taken Williams might have been with the amateur efforts of local congregations, he was himself eminently professional, bringing to his directorial work a keen eye for the nuances of a text, a rich vocabulary of theatrical techniques, and an uncompromising sense of what his actors might be capable of doing, if only they were willing to work for it.

After graduation, I drew the curtain on theatricals (or so I thought), and turned to what I had determined would be the real business of my life: writing, editing, the world of letters. I worked as a research assistant here in Sackville, and later in St. John’s, Newfoundland. I worked as an editorial assistant and as a publishing intern in Ontario. I wrote essays; I laboured at poems. Williams, meanwhile, turned to the real business of his life, which would be persistently performative in nature. He worked the Maritime summer dinner-theatre circuit; he directed college musicals; he scripted and scored material for local theatre companies. In the fall of 2003, a man named Howard Beye came to his Halifax apartment to fix a Hurricane-Juan-broken window. It turned out that this handyman moonlighted as an impresario: he had recently acquired a building on Gottingen Street, and was looking to turn the main floor into a theatre space. By the time the pane was mended, he and Williams had fixed on the idea of working together; not long afterwards, Beye approached Williams about being the artistic director for this new space. In August of 2004, my phone rang.

Williams had been commissioned by an old friend of his, the Theatre Education Coordinator at the FEZ Wuhlheide, a children’s activity centre in Berlin, to mount a production that was somehow distinctly “Canadian,” to bring to the FEZ’s English-language symposium in November of 2004. This would be the inaugural project of Williams’s fledgling theatre company, based out of Beye’s Gottingen-Street “Busstop Theatre.” Williams had christened the company DaPoPo, a nod to New York’s La MaMa theatre group, and an acronym for a mission-statement: Daring, Popular, Poetic. He was not one to start small.

The mandate of DaPoPo, Williams said, would be to “facilitate the convergence of ground-breaking, passionate artists to explore expressive possibilities.” This would be done in the context of “an actor’s studio, inspired by Grotowski’s Theatre Laboratory.” (Grotowski was nothing more than a name to me, at this point.) This “studio” arrangement would enable us “to explore a plurality of theatre traditions, dramatic theories, media and narrative structures.”

This all sounded rather impressive. In retrospect, I suppose I might have wondered why Williams was calling me, a writer and editor, at least three years out of touch not only with him but with the world of theatre, to propose this actorly venture. I might also have wondered about this Grotowski character, who was obviously so central to Williams’s scheme. After a year and a half spent working alone at my desk, however, I was drawn to the idea of working with other people, of motion, conversation, collaboration. It would be a chance to spend some time in Halifax, a city I enjoyed and where I had good friends. Most of all (remember my starry-eyedness about all things European), it would be a chance to travel to Berlin.

Rehearsals began in Halifax in mid-October. The play—which was to be called Four Actors in Search of a Nation, a tribute both to Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author and to the FEZ Wuhlheide’s commission—existed only as a skeleton, in notes for scenes and in scraps of dialogue that Williams had written and assembled. The meat of the thing was to evolve from our collective process. We had four weeks. By the end of the first of them, a few things had become clear.

For one thing, none of us were conventional actors. There was bookish me. There was Christopher Cohoon, a photographer, philosopher, poet, and erstwhile comedian, who was recently back from a two-year Master’s program at the New Mexico campus of St. John’s College. His head was bare, shaved but for an occipital fin, which gave one the impression that he moved with a rudder. There was Steph Berntson, a playwright, literary theorist, and performance poet, recently graduated from Mount Allison herself, but a born Torontonian in style. She wore a streak of blue in her hair like a feather; a small silver barbell graced the bridge of her nose, and a silver stud adorned her upper lip. Williams himself would make the fourth, and would be our director.

Secondly, it became clear that, at least in some sense, we were to be guinea pigs: that Williams had certain theatrical ideas he wanted to try out, and that he had constructed for himself a laboratory in which these experiments might be undertaken. To be fair, I believe that his ideal was for all of us, himself included, to be equal parts experimenter and experimentee; but I’m not sure that I went into the project girded with his same spirit of inquiry (though perhaps I feel it now, in retrospect). In light of this, Williams’s unconventional choice of actors began to make sense to me. Though experienced in other disciplines, Berntson, Cohoon and I were, qua actors, more or less blank slates.

Thirdly, it became clear that Williams’s theatre, like Grotowski’s, was poor not just in theory but in practice. The building was still very much under renovation: the backdrop to our vocal exercises was the sound of the band-saw, coming from behind the plastic curtain that separated the workshop from the rehearsal space. The carpenters, Jay and Margaret, were our first, incredulous, audience. Corollary to the building’s unfinishedness was the fact that there was no central heat. For the early training sessions (Williams followed Grotowski in referring to our work primarily as “training” and “research,” not “rehearsal” ), in October, it was sometimes warmer outside than in. Seeking sunshine, we’d hold meetings on the roof, or do our exercises in the gravel parking lot out back (underfoot, the detritus of broken glass and bottle caps and, occasionally, alarmingly, a sloughed condom). Sometimes we would have an audience of loitering high-school students or local ne’er-do-wells (though surely whatever menace we saw in them was mirror to our own provocation, walking like badgers or stretching like cats in what was, after all, very much their neighbourhood.)

The final thing that became clear to me in that first week of training was that I was in way over my head. This theatre that Williams had in mind was an all-or-nothing proposition. My visions of afternoons spent working on my poems evaporated. My creativity would go into the training sessions; at the end of the day, there would be nothing left. There was no room for dabblers here. (I choose that word carefully. To dabble is, figuratively, to take a superficial interest in something; literally, it is to move without conviction. The Grotowskian/DaPoPoian actor must learn to account for his minutest actions: “Everything we undertake must be done without too much haste, but with great courage,” says Grotowski, “in other words, not like a sleep-walker but in all consciousness, dynamically, as a result of definite impulses.” The dabbler, then, is to theatre what the dauber is to painting, or the scribbler to poetry.)

Furthermore, I realized that I was going to have to learn to be creative in a way that was entirely foreign to me. Talking would be important, here, but moving would be more important. We were to learn to think not with the mind but with the body, by way of a physical training program which, I can see in retrospect, must have borrowed its rigour from the quest of Grotowski’s “holy actor” to “eliminate his organism’s resistance”:

Imagine you have a metal band around the chest. Stretch it by means of a vigorous expansion of the trunk…. Headstand with the feet together against the wall. The legs slowly open as wide as possible…. Keeping the legs together, jump up onto a chair. The impulse for the jump does not come from the legs but from the trunk…. Starting from an upright position, bend the body backwards to form a “bridge” until the hands touch the ground behind…. Walk on the hands and feet, with the chest and abdomen facing upwards….

“Lie on the floor,” Williams would say, his voice taking on an authoritative timbre. “Feel the floor along your spinal column. Put your hands at the base of your ribs: feel your torso expand, contract. When you feel the impulse to make sound, let sound happen. Do not think. Obey the impulse.”

Do not think: this was anathema to me. How could one sum without cogito? I was (am) a word person. If I had had to draw a caricature of myself, I would have drawn a lump of grey matter with legs for locomotion. As rehearsals went on, however, I was forced to admit the rest of my body to the picture. My body changed, in fact: it became stronger, more capable. It also became bruised. My mind changed, too: at times, in the thick of our training, it would come up wordless. Grotowski might have seen this as development; to me, it would have been alarming, had I not been too exhausted to take note.

Gradually, out of this course of training, our play emerged. It would involve, as props, only four chairs: the spare, stackable seats which had formed the four points of our rehearsals’ compass. It would be punctuated by scenes in which we played ourselves, talking—acknowledgement and parody of our collective tendency (detrimental, in Grotowski’s terms, but for us seemingly unavoidable) to talk first and act later. It would incorporate sections born of text written by each of us. There was a framing diptych I had written, in which a Williamsian director, recruiting actors for a poor theatre, was juxtaposed with (and superimposed on) a land speculator, recruiting immigrants for a poor country. There were a pair of provocative nursery rhymes, by Berntson: in lieu of the falling of London Bridge there was the disappearance of the Beothuk; in lieu of the ashen posies there was the Acadian Expulsion. Cohoon’s piece was a kind of lyric memoir, a story out of childhood about being lost and found. From Williams’s original script we took a series of meta-theatrical monologues, and a parodic psalm. Interspersed among these verbal sections, there were non-verbal scenes. These had evolved directly from our training; they were meant to evoke a national history not literal but mythic: birth, growth, atastrophe, construction, dissolution—nation-building as set forth in grunts and wriggles, shrieks and moans. This sounds like a hodgepodge, I realize—but I did come to feel that the play had a kind of unity; it was tied together, if not by narrative, then by a series of recurring themes and forms.

We had scheduled two preview performances in Halifax, the week before our departure for Berlin. We were in the business of research, after all. If theatre is, at its most basic level, the conjunction of actor and spectator—as Grotowski maintains—our research would be incomplete until we formally introduced the latter. Our idea was to bring in friends and colleagues, perform the show for them, hold a reception, and solicit their response.

The first night’s performance went well, I thought, all things considered. It’s not that I felt the technical advances, the muscle-memories, of my training combining alchemically in the crucible of performance, as I might have wished—but the play did run smoothly, one scene followed another without hitch, and there was a general sense of exhilaration at show’s end. My friend Sylvia Nickerson, with whom I’d been staying while in town, was congratulatory but cagey when I sought her out at the reception. On the way home, I asked her what she’d thought. “I’m glad I saw it,” she said, “but I’m not sure I liked it. Perhaps I’d have to see it again.” She thought for a moment. “It’s very dark.”

I was taken aback. As I reran the performance in my head, however, I could see that she was right: there were moments of conciliation in the play, of connection between characters and between actors, but they were by far outnumbered by moments of conflict and discord. How, I wondered, had four basically fortunate Canadians created a play about nationhood that was so dark? Was this compensatory darkness: a guilty need to tip our hats to those violent histories from which we felt ourselves to have been exempted? Or were we merely tapping into the sense in which no one is exempted from the violence of history? Or perhaps—and I found this possibility the most unsettling—there was something in our very process of creation, with its emphasis on pushing the body to its limits, on poverty, asceticism, self-effacement, which brought out what was dark in us, rather than what was light.

The day before we were due to leave for Berlin, I asked Williams the question that I probably should have asked him on the telephone in August. Towards a Poor Theatre: can I borrow that book? I thought might like to read it on the plane. I opened the book that evening before I went to sleep, and read a page or two from the title essay. I slammed it shut. I didn’t pack it in my luggage the next day.

Here was a book, composed in decades before I was born, published in a country to which I’d never been, and translated from a language I’d never spoken—yet in it I found an uncannily accurate description of the process in which I’d been engaged for the past four weeks. I would read this book, I thought, but not here, not now. From the few pages I’d looked at, I’d surmised that this book might confirm for me not only the challenge and interest of our endeavour, but those things about it I found most disquieting. I wasn’t sure I wanted to get into that now, with our rehearsal period behind us and our performances ahead.

3.

I have often thought that everyone has two careers: the one she pursues, and the one she’d like to pursue in another lifetime. For a long time, acting was that second career for me. This began when I was about five. My parents took me to see a production of Peter Pan, in which a young woman played the title role. I was completely Neverlanded. I determined to become an actor so that I, too, could play Peter: glory, androgyny, flight—what more could a five-year-old ask for?

As I grew older, and set myself a writerly course instead, the actor-me became the looking-glass self. Where writing was solitary, acting was communal. Where writing sought a kind of timelessness, acting

embraced time: time was its medium. While writing was predicated on a sort of separation between the artist and the art, acting was predicated on their unity.

There is, of course, a long tradition of writers who, for better or worse, have dabbled in the theatre. My favourite picture of Iris Murdoch shows her “sewing costumes for undergraduate dramatics.” In a memoir about James Merrill and David Jackson, Alison Lurie writes of the early days of the Poets’ Theatre, in Cambridge, Mass.:

This was an informal, somewhat disorganized collection of young writers committed to putting on plays in verse: both those of classic authors like Yeats, and ones they wrote themselves. Among them were John Ashbery, Edward Gorey, Frank O’Hara, Donald Hall, V. R. Lang, and Richard Wilbur. Today this list sounds impressive, but in the 1950s all these people were unknown, and the Poets’ Theatre was a broken-shoestring operation, mocked in the Harvard Crimson, always running over budget and into crisis.

There are also, of course, writers who have done much more, in the world of theatre, than dabble (some of them included in the list above, in fact); but it’s with the dabblers that I’m forced to cast my lot.

I suspect that this kind of dabbling tends to be predicated on certain misconceptions. A writer, even a famous writer, labours in obscurity, insofar as she is seldom present when her work is read—nor, rankly, would she often want to be. Yet might she not see in the actor visions of ovations and roses—of instant gratification, that is to say? (A real actor might tell me that this gratification, if it comes at all, is far from instant, and that, when it comes, if it’s sincere, it is not for the person but for the work.)

Or, again: a writer creates dashing characters with fascinating lives, but when she gets up from her writing desk, she’s still her dowdy self. Might she not see, in acting, the allure of transformation—of actually becoming what she creates? (A real actor might tell me that one acts, one doesn’t become—at least not if one wants to retain one’s sanity.)

This fantasy of becoming must be somewhat widely shared, however, amongst writers. In 1995, The New Quarterly sent round a survey, asking writers not which literary character they would like to have created, but which literary character they would like to be. There was one ground rule: “no cheating—no Anna Karenina without the train.” The responses were many and varied. Russell Smith wanted to be P. G. Wodehouse’s character Psmith. (I’m still not sure if this was for the prose or for the clothes.) Steven Heighton wanted to be Tom Jones, for “the chance to be guided through the rogue’s galleries and rowdy districts of his novel by the generous hand of Henry Fielding.” Sandra Sabatini wanted to be Shakespeare’s Kate, that “untamed shrew,” and to be her “in black leather and heels. Red lipstick, seamed stockings, and gloves. Make obedience dangerous.”

My own long-standing confusion of acting with becoming, the represented with the real, has been a source of trouble for me. When, in grade one, we did a unit on dinosaurs, and watched a claymation video in which a tyrannosaurus cheerfully dismembered a triceratops, I ran from the classroom in tears. “It’s only a movie” meant nothing to me. Hundreds of movies later, my condition has not improved; if anything, it’s been exacerbated by my now keener sense that most of the violence we imagine has its counterpart in fact. When people say, “That’s not for the faint of heart,” I know they’re talking about me.

A few years back, my partner—John—and I were visiting friends in Newfoundland. They have a son named Jonah, at that time a goldilocked and engaging two-year-old, with whom we were both quite taken. John and Jonah had a game. John would loom up on tiptoes, with his hands in the air, and come stalking towards Jonah, growling.

“You’re not a monster,” Jonah would say.

John would continue to advance.

“You’re not a monster.”

John would loom larger still.

At this point, Jonah would begin to retreat by half-steps, saying all the while, in a breathy giggle, “You’re not a monster, you’re not a monster.” This was becoming a question.

The game would end just at the point when Jonah was prepared to turn and flee. John would concede that Jonah was right—he was not, in fact, a monster—and harmony would be (at least temporarily) restored.

I was reminded of this game the other day, when I sat down, finally, with Towards a Poor Theatre. Several months had passed since our trip to Berlin. Our play, performed in three very different venues for three very different crowds, had been well-received. (The first show was the commissioned one, for a group of elementary-school children at the FEZ Wuhlheide; the second was for senior drama students at John F. Kennedy International High School; the third was for a group of adults—many of them artists and performers in their own right—at a small, avant-garde gallery in the east part of the city.) In 1966, Grotowski and Ryszard Cieslak, a virtuoso actor from the Laboratory Theatre, gave a course at the Institut des Arts Spectaculaires in Brussels. Franz Marijnen took notes. Here, he describes an exercise called “Tiger”:

This exercise is obviously intended to make the pupil let himself go completely and, at the same time, set the guttural resonator in action. Grotowski participates in the exercise himself. He plays the tiger attacking his prey. The pupil (the prey) reacts….

Grotowski: “Come closer … Text … Shout … I am the tiger, not you … I am going to eat you…”. In this way he goads the pupil on to enter fully into the game. It is remarkable how the pupils are carried away by the exercise.

Reading this, I had a flashback to a scene I’d worked on with Williams years ago, in that undergraduate production of Twelfth Night. I was playing Viola. Viola—disguised as Cesario, a young man in the duke Orsino’s service—loves Orsino. Orsino (he thinks) loves the lady Olivia. Olivia loves Cesario, to whom she has just (she thinks) been wed. Act five, scene one, finds us at the juncture at which Orsino learns of Cesario’s seeming betrayal. He turns on his heretofore loyal servingman:

O thou dissembling cub! what wilt thou be

When time hath sow’d a grizzle on thy case?

Or will not else thy craft so quickly grow,

That thine own trip shall be thine overthrow?

Williams, as director, was trying to get Orsino to be more menacing. The actor tried one thing, then another: righteous indignation, cold anger, inchoate rage. Finally Williams said, no no, like this, and stepped into the role. He dispensed with all bluster. He came very close to me and reached up as if to touch my face. He spoke in a voice that scarcely broke a whisper, letting the words fall onto the silence one by one:

O thou dissembling cub

You’re not a monster, I thought. The gesture of Williams’s outstretched hand went from tender to violent:

What wilt thou be when time hath sow’d a grizzle on thy case?

His voice rose to a stinging pitch. Time, grizzle, case: he spat them. I recoiled. “You’re not a monster,” I thought. “You’re not a monster, you’re not a monster.”

It was remarkable how the pupil was carried away by the exercise.

This story is in part about Williams’s ability as an actor—and my own comparative lack thereof: clearly, this theatre business required some balance between acting and becoming, belief and disbelief, which I had not (have not) yet mastered. But there’s also something in this story which speaks, indirectly, to the discomfort I felt when I ventured into Grotowski’s writings. Here is an excerpt from a 1964 interview that Grotowski did with Eugenio Barba:

What strikes one when looking at the work of an actor as practised these days is the wretchedness of it: the bargaining over a body which is exploited by its protectors—director, producer—creating in return an atmosphere of intrigue and revolt.

Just as only a great sinner can become a saint according to the theologians … in the same way the actor’s wretchedness can be transformed into a kind of holiness….

… If the actor, by setting himself a challenge publicly challenges others, and through excess, profanation and outrageous sacrilege reveals himself by casting off his everyday mask, he makes it possible for the spectator to undertake a similar process of self-penetration. If [the actor] does not exhibit his body, but annihilates it, burns it, frees it from every resistance to any psychic impulse, then he does not sell his body but sacrifices it. He repeats the atonement; he is close to holiness.

To me this sounded rather like exchanging one kind of wretchedness for another: what’s the difference between the victim and the martyr, here, but rhetoric? Even if we ascribe something of the fanaticism of

Grotowski’s language to the translation, there’s an unsettling subtext. I recalled Grotowski playing the tiger to the pupil’s “prey.” In another interview (this from 1967), Grotowski says: “I was first trained as an actor, then as a producer…. Gradually, I developed and discovered that to fulfil myself was far less fruitful than studying the possibility of helping others to fulfil themselves.” Is it possible that Grotowski was asking his actors to sacrifice themselves not so much to art as to Grotowski?

My concern on this front deepened when I began to read accounts of Grotowski’s most celebrated productions. There is Akropolis, an adaptation of a drama by Wyspianski, transplanted from an old cathedral to a concentration camp, in which the actors play a “group of human wrecks”: “The characters re-enact the great moments of our cultural history; but they bring to life not the figures immortalized in the monuments of the past, but the fumes and emanations from Auschwitz.” There is Dr. Faustus, an adaptation of Marlowe’s play, in which, at drama’s end, Faustus is “no longer a man, but a panting animal, an unclaimed, once-human wreck moaning without dignity.” There is, perhaps most famously, The Constant Prince, an adaptation of the play by Calderon de la Barca, which deals specifically with sacrifice. The audience looks down on the actors, as into an “arena” or “operating-theatre”: “A ball is held at the court. The cries of the tortured form the music of the minuet.” In still photographs from the performance, the actor Ryszard Cieslak, in the title role, his body refined not by torture but by “training,” looks indeed like a man on the road to calvary.

Could it be that the self-sacrifice of Grotowski’s “total acting” produces actors best suited to a single role: the “human wreck”? I thought back to our own production, with its grunts and groans, its howls and whimpers.

In The Grotowski Sourcebook, a more recent treatment of Grotowski and his techniques, I found an article by the theatre critic Harold Clurman, which gets at the source of my concerns:

The exercises of Grotowski are intended to make the actor surmount his supposed breaking point, to stretch him vocally and bodily so that he can hold nothing back; to remove his restraints, those “blocks” imposed by his usual social comportment. He is wracked so that he becomes nothing but his id and thus releases what he primally is. Whether he actually succeeds in this, or whether it is altogether desirable that he do so, is another matter which I have no desire to question or capacity to determine at this juncture.

The emphasis is mine.

Clurman’s article, for all it confirmed some of my fears, also helped me to understand a strange phenomenon. As alarmed as I had been by my friend’s diagnosis of our production—dark—I had come to feel much better about the play after we performed it in Berlin. Scenes which had felt alarmingly provocative when we did them for an audience in Halifax had felt appropriate, there—even when performed for an audience of schoolchildren. How could this be?

The children were quicker to laugh, for one thing, in lighter moments of the play, than our Halifax audience had been; this helped us draw these moments out, as counterbalance to the darker material. But there was perhaps something more. Clurman says, of Grotowski, “Born in 1933, he is the witness and heir—as are most of his actors—of his country’s devastation. The mark of that carnage is on their work. It is an abstract monument to the spiritual consequences of that horrendous event.” It occurred to me, absorbing the reaction to our play of those German schoolchildren, that they, too, were witness and heir to devastation. Canadians are used to thinking about national identity in terms of cheerful call-in sessions on the CBC. A dark play about national identity will of course be jarring to us. But to children brought up with the Holocaust as the unforgiving centre of their history curriculum, the darkness of a play about national identity must seem natural—even requisite. It occurred to me that these children knew a good deal more than I did about the monstrous.

I remembered something that Williams had told me once, about an experience he’d had shortly after returning to Canada as an adult. He had woken up one morning to the noise of a parade. Looking out his window, he had seen the usual complement of clowns and city fathers, but also ranks of marching men in uniform—veterans, cadets. The whole city seemed to be waving flags. Now, a typical Canadian might have recognized this as Canada Day: our annual quixotic attempt to shore up our national identity, three days before the fourth of July. Williams’s reaction, however, was horror. In Germany, goose-stepping and flagwaving have distinctly different connotations.

I began to understand part of Williams’s attraction to Grotowski. Here was a kind of theatre that might allow him to respond to a commission that must have been troubling to him: to create a play about nationhood. And he must have recognized—better, perhaps, than most Canadians do—that our seemingly placid North American history comes, in fact, with its own complement of horrors; that we too are heirs to violence, whether or not we choose to bear witness.

Perhaps, I thought, there was something to this method of Grotowski’s—so long as one didn’t take it too far. This was the position I had reached by the time I got into the final sections of Towards a Poor Theatre. One of these is devoted to Grotowski’s “Skara Speech,” a talk he gave at the Skara Drama School in Sweden in 1966. He is speaking, once again, about the actor’s art—what he calls “total” acting, the utter gift of self. “I do not mean that you have to be a masochist,” he says.

Oh really?

I began to read more closely:

When it is necessary, when your director has given you a task, when the rehearsal is in progress—at these moments you must be unbound by time and fatigue. The rules of work are hard. There is no place here for mimosa, untouchable in its fragility. But do not always seek sad associations of suffering, of cruelty. Seek also the bright and luminous. Often we can be opened by sensual recollections of beautiful days, by memories of paradise lost, by the memory of moments, short in themselves, when we were truly opened, when we had confidence, when we were happy. This is often more difficult than to penetrate into the dark stretches, since it is a treasure we do not wish to give. But often this brings the possibility of finding confidence in one’s work, a relaxation which is not technical but which is founded on the right impulse.

Perhaps, then, it was not that we had taken Grotowski’s method too far in our own play, but that we had not taken it far enough. Finding it easier “to penetrate into the dark stretches,” we had left “the bright and luminous” un-mined. It was Pandora’s box, the lid slammed shut too early.

In a 1967 interview in New York, Grotowski returned to this idea of the actor’s gift of self. To whom is this gift addressed? It must not be addressed to the audience, he says, as this leads to narcissistic “flirtation”—and it must not be addressed by the actor to himself, as this is “the shortest way to hypocrisy and hysteria.” The actor must give himself to the research: “In that sense it is like authentic love, deep love. But there is no answer to the question, ‘love for whom?’” In the end, he calls this unknowable “whom” the “secure partner”: “One need not define this ‘secure partner’ to the actor, one need only say ‘you must give yourself absolutely’ and many actors understand.”

Even after my months of thinking, with body and with brain, I had to concede that I was not among these many.

And yet.

There are, as I have said, writers who dabble in theatre. There are also, as I’ve said, writers who go beyond mere dabbling: who embrace theatre and involve themselves in it deeply, and who leave it transformed. But there must also be a third category: writers who recognize the theatre as a separate art form, to which they will always be outsiders, but from which they may nonetheless learn. For theatre can be metaphor.

Richard Outram’s poem-sequence Benedict Abroad features a character who is an actor. On the night of her virtuoso performance, we are told, she “was made somehow acutely aware / that the gods were restless tonight, if watching intently / as always, and that their perspective was other.” In his book on Outram’s work, “Her kindled shadow…”, Peter Sanger reminds us that the gods, as well as being Gods, are “the cheapest theatre seats in the upper back balcony.” In a subsequent performance, this same actor has a scene with a “firecat,” which is so convincing that her director fears she’s “skipped a groove.” The reader, likewise, wonders: back in her dressing room, the actor stanches her wounds.

Not until nearly dawn did she leave the Lyric,

long dark, slipping unnoticed out the stage door.

And headed for her digs, exhausted, escorted

by Lions that stared down the last pale stars ever.

What are we to make of this?

Well, there are monsters and there are monsters. Perhaps the artist must not altogether shun their company. Furthermore, if we see in the firecat a conjunction between theatre and poetry (prompted by that Lyric), we might say that there are tigers and there are Tygers. And we might find here a tentative answer to Grotowski’s “for whom.” It is a double answer. A true actor plays both to the gods and to the Gods. Perhaps this answer holds for the poet, too.

Works Cited

“Changing Places: New Quarterly Writers Choose Literary

Alter-egos.” The New Quarterly 20.2 (2000): 46-65.

Clurman, Harold. “Jerzy Grotowski.” The Grotowski

Sourcebook. Ed. Richard Schechner and Lisa

Wolford. London: Routledge, 1997.

Grotowski, Jerzy. Towards a Poor Theatre. Holstebro,

Denmark: Odin Teatrets Forlag, 1968.

Lurie, Alison. Familiar Spirits: A Memoir of James Merrill

and David Jackson. New York: Penguin Books, 2002.

Outram, Richard. Benedict Abroad. Toronto: St. Thomas

Poetry Series, 1998.

Sanger, Peter. ‘Her Kindled Shadow…’: An Introduction to

the Work of Richard Outram. Rev. ed. Antigonish,

N.S.: Antigonish Review, 2002.

Williams, GaRRy. “Text Montage.” Four Actors in Search of

a Nation Unpublished draft play script. 2004.

—. “What is DaPoPo?” Unpublished mission statement. 2004.

Wilson, A. N. Iris Murdoch As I Knew Her. London: Arrow

Books, 2004.

The photographs which accompany this essay were taken by John Haney during DaPoPo’s Berlin performances of Four Actors in Search of a Nation, and during a post-performance photo call at the FEZ Wuhlheide. The actors, all pictured in the photograph above, are (from left to right) Steph Berntson, Christopher Cohoon, GaRRy Williams, and Amanda Jernigan.

DaPoPo gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts towards the travel costs of individual actors.