What’s Natalie Hryciuk Reading?

By Natalie Hryciuk

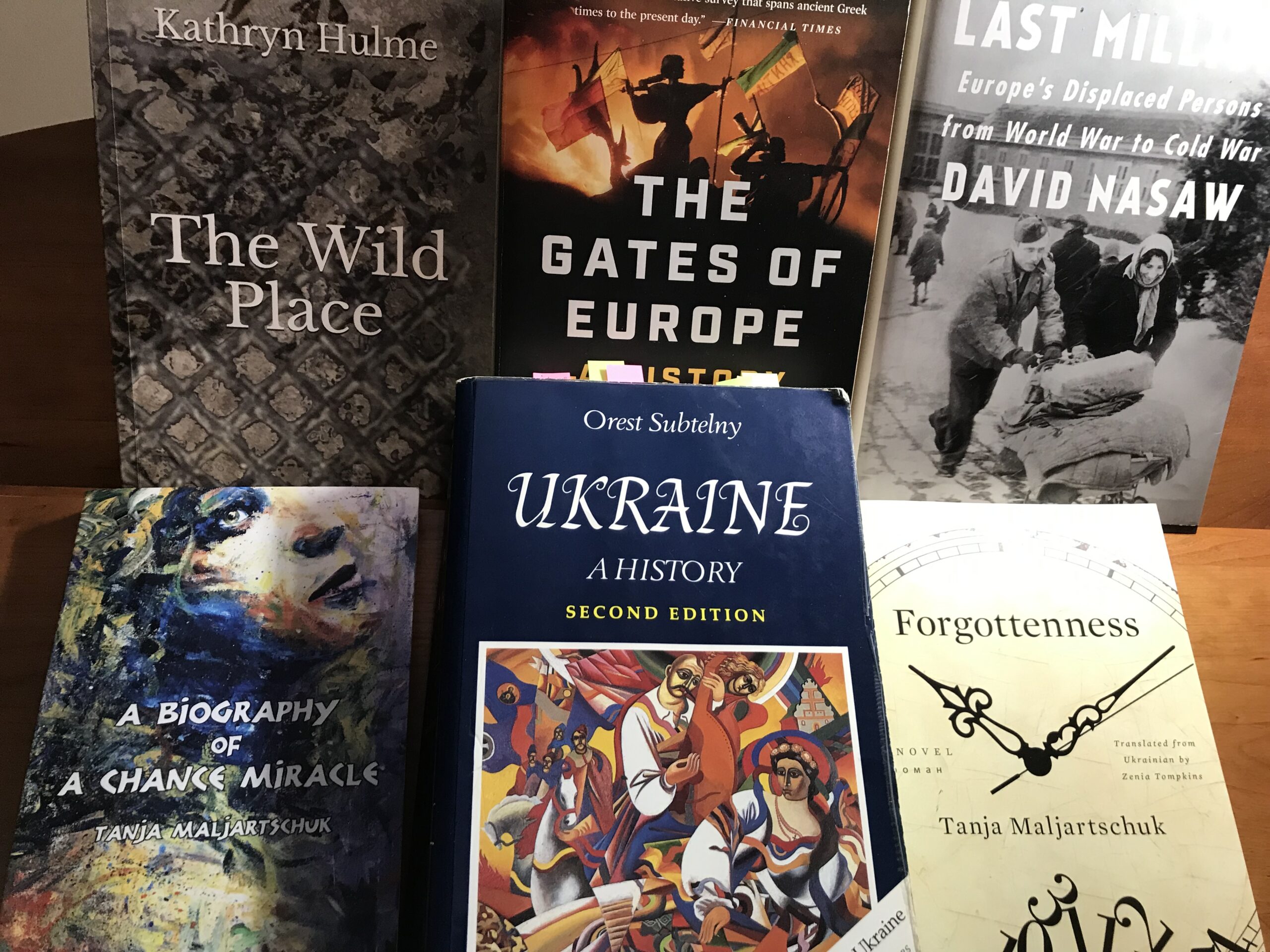

I’ve always enjoyed reading a blend of non-fiction, fiction and poetry. A few years ago, I began reading a series of non-fiction books about the history of Ukraine, where my family originates. I wanted to know more about the political and historical events that have shaped Ukraine, and how these forces shaped my parents and, in turn, me. This need intensified in the months after Russia invaded Ukraine. Two texts were especially useful: Ukraine, A History, (second edition), by Orest Subtelny, a Canadian historian, and The Gates of Europe, A History of Ukraine, by Serhii Plokhy, who teaches at Harvard. Another valuable resource was David Nasaw’s book, The Last Million, Europe’s Displaced Persons from World War to Cold War, which helped me to understand my parents’ experiences as displaced persons.

My mother, who worked as a Nazi slave labourer during World War 2, found herself among the many Eastern Europeans who spent the post-war years in DP camps in southern Germany, waiting for a country to accept them. David Nasaw’s book, which is about the events of more than 75 years ago, is a timely read during the current global migrant crisis, and the displacement of 95% of Gazans. Nasaw, an American historian, also reminds us that no nation wanted to take the 200,000 Jewish people who remained trapped in Germany after the war, and that it was only after the partition of Palestine and Israel’s declaration of independence that these Jewish survivors were able to leave the displaced persons camps.

“I wanted to know more about the political and historical events that have shaped Ukraine, and how these forces shaped my parents and, in turn, me.”

A more personal account of displacement in the post-war DP camps is The Wild Place, a memoir by Kathryn Hulme. Written from her point of view as an UNRRA director, it’s a beautifully written story that engages both your heart and your intellect. She describes army truck convoys departing the camps filled with displaced people who were heading to new lives in countries like Belgium, Holland and England, which had accepted them as economic migrants, “country after country reaching in for its pound of good muscular workingmen’s flesh.” My father was one of these economic migrants, among the first to leave for work in a Belgian coal mine. Thanks to Hulme’s memoir, I experienced the thrill of discovering he left the camps in May 1947.

After this intense immersion in non-fiction, I was curious to read some fiction by a contemporary Ukrainian writer whom I’d come across in a book review. Tanja Maljartschuk is an accomplished and versatile writer who writes in both Ukrainian and German, having moved to Austria in 2011.

She has published short stories, essays, two novels, one YA novel, as well as poetry. I have just finished reading Forgottenness, which received the BBC Book of the Year award. Published in 2016, it was translated into English (by Zenia Tompkins) this year. I have also read her other novel in translation, A Biography of a Chance Miracle.

Twentieth century Ukraine is the historical backdrop for Forgottenness, which weaves together the story of a real-life Polish/Ukrainian activist named Viacheslav Lypynski with the fictional story of the writer-narrator, who decides to explore and write about Lypynski’s life. The narrator struggles with bouts of agoraphobia and other mental health issues. In an interview with Craft magazine [craftmagazine.net], Maljartschuk describes herself as “a person of a pessimistic-sarcastic nature.” She is known for her use of satire and absurdism, and is not afraid to reach into dark places with humour; in one scene the narrator runs out of food after a pathological bout of overeating, but cannot go out to buy groceries because of her agoraphobia. However, just as she seems to be spiraling downwards, the narrator gives us vivid, chapter-length descriptions of her Grandma Sonia and her Grandpa Bomchyk. Both were damaged by traumas inflicted during the Soviet era, but became, above all, survivors. I find these characters riveting. Grandma Sonia’s lesson on how to wash floors is emblematic of her pragmatic approach to life: “Trying to wash yourself clean from tragedy your whole life was pointless. Washing floors taught you that. No matter how much you scrubbed, dirty streaks would emerge regardless.” Grandpa Bomchyk is defined by his giggling, and the narrator describes his body as a “receptacle for the accumulation of unutilized laughter, which is why, over the years, as the reasons for laughter grew fewer and fewer, his body began to increase in size.” By resurrecting memories of her grandparents, the narrator is able to move past her own “shame and powerlessness.”

In the Craft magazine interview, Maljartschuk describes faith as an ethical concept that one has to work at strengthening, for “disbelief is what the enemy uses to destroy his victims. Disbelief is at the heart of powerlessness.” She says the war has made it impossible for her to continue writing fiction or poetry; she realizes “literature does not prevent the most senseless wars from happening again; dictators and tyrants are still there, and they even read books.” Instead, she has turned to philosophy, reading Hannah Arendt “as a form of psychotherapy.”

Although the novel I have just finished reading may be the last one Maljartschuk will ever write, in spite of her despair at the state of the world, she has also inherited the pragmatism of her grandparents’ generation. When she observes a peace installation at the town hall in Osnabrück, she notices that pitchforks are shown with their tines hammered into a block of wood to symbolize non-violence. Maljartschuk laughs when she sees this; wouldn’t it be useful to keep at least one pitchfork handy in case you have to defend yourself? I will miss her spirited, grounded approach to life, and the dark humour bubbling up in her fictional voice as she describes the bleakest of circumstances.

Natalie Hryciuk is an emerging writer living in Surrey, B.C. She is a first-generation Ukrainian Canadian, and explores that aspect of her identity in some of her writing, including both poetry and prose.

Photo by Andriyko Podilnyk on Unsplash