Finding the Form with Eva-Lynn Jagoe

By Eva-Lynn Jagoe

When Vinh Nguyen asked me to write something for “Scatterings,” I felt so honoured because the writing in that series has been so amazing. In trying to find the form of a piece, I find that I tend to write with a particular reader in mind. For “The Finca,” I was thinking of Vinh, who I know to be a beautiful subtle writer and a perceptive reader. I wanted to evoke, for Vinh and readers like him, the nostalgia of place and time that I feel so strongly. I knew that, to do this, I needed to linger on sensory imagery and really try to express the longing I feel when I can’t sleep and lie in bed tracing, with minute detail, the rooms of the house, the touch of the cool marble tiles on my bare feet. Or when I think about the saffron taste of my grandmother’s paella, jostled by cousins at the patio table in the heat of the midday shade.

Vinh Nguyen asked me to write something for “Scatterings,” I felt so honoured because the writing in that series has been so amazing. In trying to find the form of a piece, I find that I tend to write with a particular reader in mind. For “The Finca,” I was thinking of Vinh, who I know to be a beautiful subtle writer and a perceptive reader. I wanted to evoke, for Vinh and readers like him, the nostalgia of place and time that I feel so strongly. I knew that, to do this, I needed to linger on sensory imagery and really try to express the longing I feel when I can’t sleep and lie in bed tracing, with minute detail, the rooms of the house, the touch of the cool marble tiles on my bare feet. Or when I think about the saffron taste of my grandmother’s paella, jostled by cousins at the patio table in the heat of the midday shade.

It was a pleasure to write the essay, and I wrote it quickly. The first person, which is me and not me, is a voice that I am familiar with, since my previous book is a memoir. Recently, I’ve been trying to write a gothic climate novel about the finca and my family’s legacy. My grandfather was a British electrical industrialist in Barcelona, so I want to write a novel that looks at hydroelectricity in Cataluña and the repercussions of modernization in the intimate space of a family and a place. I have been pushing myself to write characters who are very different from myself, and to use the third person. I am having a pretty bumpy time. Sometimes, it’s totally fun to make up situations and character traits, other times I feel that really I have no imagination and that I’m just fictionalizing reality.

The other day, a writer friend told me that I should just write in the voice that comes naturally. I whined, “But I don’t want to write another memoir!” This is something that I really need to figure out, since the novel draws so much from my own family and the finca. How am I going to write this? Why am I so averse to writing it as memoir? In part, I think, this has to do with fear of hurting people. My first memoir was already so intimate and painful that I still cringe to think about my parents reading it.

My uncle, who appears in “The Finca” as Uncle Tony, read it and wrote me an email headed “Slightly Petulant,” with a link to a Leon Redbone song, “Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone.” My heart sank when I read it. I regretted that I had written about him and my aunt, and felt a paralysis about the writing that I was currently doing for the novel, which was about them.

After some thought, I wrote this reply: “You know what they say, dear uncle… ‘For the wolf of a writer, the family is a crowd of sitting ducks.’ No, but seriously, I wrote this piece because it felt true to me, but you know how it is with writing, even real people become characters who demand to be written a certain way. Any autobiography or biography is both a truth and a fiction, so how much more so in full fiction?”

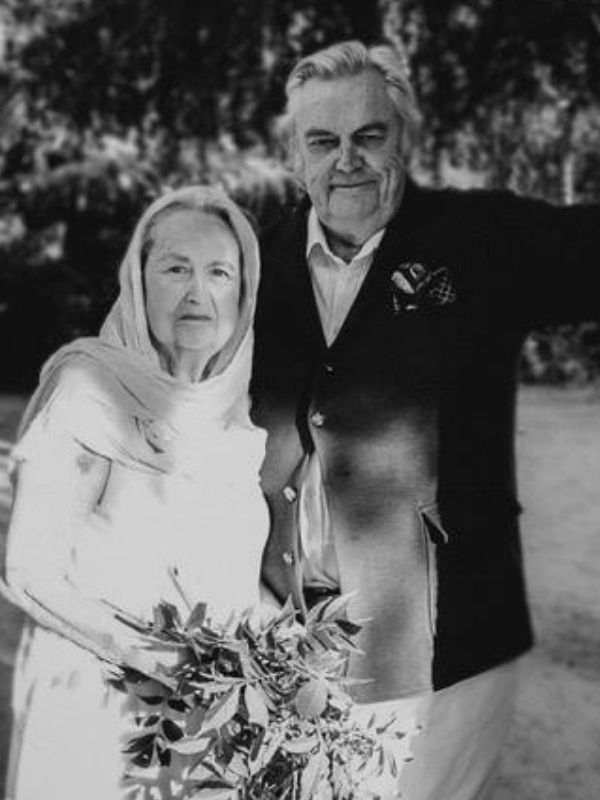

We’ve been writing back and forth since then, him telling me about how the finca is more bohemian than ever, now that he and my aunt live in it full time, me asking him questions about family history. He sent me these two pictures the other day, which haunt me. I stare and stare at my aunt’s young 1972 beauty and her aged 2020 face, seeing my mother, seeing my aunt Chichi, and seeing myself. It’s all so deep and tangled in me that I wonder how I’m going to write my way into and out of it.

Eva-Lynn Jagoe’s Take Her, She’s Yours (punctum books, 2020) is a memoir about psychoanalysis, sexuality, and self-possession. She is a professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature at University of Toronto.

Photos courtesy of Eva-Lynn Jagoe. Cover image by Pascal Habermann on Unsplash