Finding the Form With Matthew King

By Matthew King

I remember the first time I identified a poem as an irregular sonnet: it was Robert Frost’s “For Once, Then, Something”, which was in an anthology we used in one of my highschool English classes. I don’t know why I thought it was a sonnet; I just remember insisting that it was. Now, having more experience of the appearance of these things, when I see a poem with that almost-square look on a third of the page or so, the first thing I do is count the lines–fifteen, it turns out, in the Frost poem; close enough. A regular five feet per line, too, unrhymed, but not the familiar Frostian blank verse: a trochee, a dactyl, then three more trochees, eleven syllables per line, like clockwork. (I can’t stop counting on my fingers as I re-read what I’ve written here.) And a turn announces itself, too, but soon, as the seventh line begins, emphatically: Once.

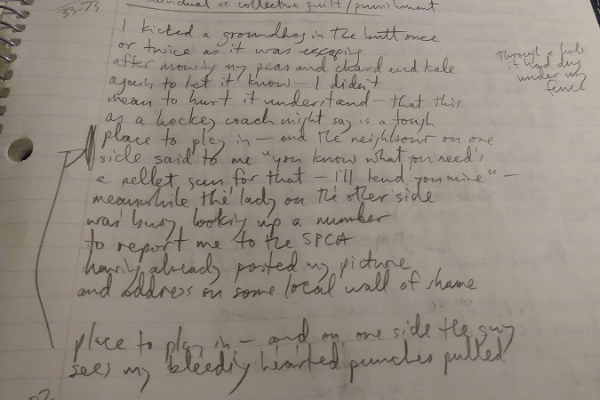

I used to say it was an arbitrary life-goal of mine to write as many sonnets as Shakespeare. Some poems are easier to count toward that than others. Should I count “Yes, I Kicked a Groundhog in the Butt Once”? Arguably it’s basically a blank-verse sonnet, but its feet are running all over the place, maybe befitting such a rambling little yarn (which turns one way, then another)–truth be told, it’s really more decasyllabic than pentametric. It got to be that way because it was always going to start with “I kicked a groundhog in the butt once”, which needed just a little affirmation to work itself up into a nice line of pentameter. From there, the rest of the story (which is admittedly a half-imagined mash-up–the lady calling the SPCA is only a personification of my own superego, and the guy with the pellet gun was, in real life, talking about chipmunks) told itself, fortuitously enough, in thirteen more just-about-ten-syllable chunks–and there I had it, that respectable sonnet-esque look. It ends with a rhyming couplet, but as a coda to its fourteen-line body, the moral of the story, signalling that it’s more comment than content by separating itself and dropping a syllable in each sing-songy, just-so line.

Well, this is a pretty serious take on such a goofy little poem. But it’s a goofy little poem on some serious business. I don’t mean the business of maybe getting strung up for animal cruelty because I kicked a groundhog in the butt once or twice (which indeed I did); I mean the business of investing yourself in some precarious thing, which you were always afraid was nothing but ridiculous anyway, then watching as something, making a mockery of your defensive pretenses, comes along and destroys it all in minutes, munch-munch-munch, carrying out a phenomenological reduction of your endeavours to their essential vanity. As Hegel writes (and this is his only published joke, as far as I know, but it’s a good one), non-human animals demonstrate that they are “profoundly initiated” into an ancient wisdom about the non-being of the things of sense-experience when “they do not just stand idly in front of sensuous things as if these possessed intrinsic being, but, despairing of their reality, and completely assured of their nothingness, they fall to without ceremony and eat them up.” Back when I would see rabbits robotically consuming the grass at the side of the path as I walked home from my graduate seminars, it amused me to think of the rabbits as little Hegelian nihilists, but the joke wasn’t so funny anymore when I started trying to grow things–not so much for me to eat as to make something of myself–and the annihilating rodents showed up, cutting me down to size.

Shakespeare didn’t actually write a huge number of sonnets: 154, officially, so, at, say, one a week, I would’ve achieved my old arbitrary life-goal in about three years. The poetry-writing goals I have these days seem to me a whole lot less arbitrary; my defenses are a whole lot more pretentious. The groundhogs are hibernating as I write, but they’ll be back, again and again, to eat up the fruits of my labours. And I still–I hope–won’t have the heart to really hurt them.

Photos courtesy of Matthew King and Gary Bendig.