On Isabella Wang

By Selina Barker

Isabella Wang was born in Shandong, China, and lived in Beijing until the age of seven when she immigrated with her parents to Vancouver, British Columbia. A lifelong reader and aspiring writer, she volunteered at Room Magazine for their 2018 Growing Room Literary Festival. While working as an intern, she curated and published an interview series focused on authors at the 2019 festival.

Her writing and work with the festival propelled her to the Submissions Coordinator role and a summer position as Web Content Coordinator. She is also coordinator for the Dead Poets Reading Series, a Vancouver-based poetry reading series. All this while she pursues a double major in English and World Literature at Simon Fraser University.

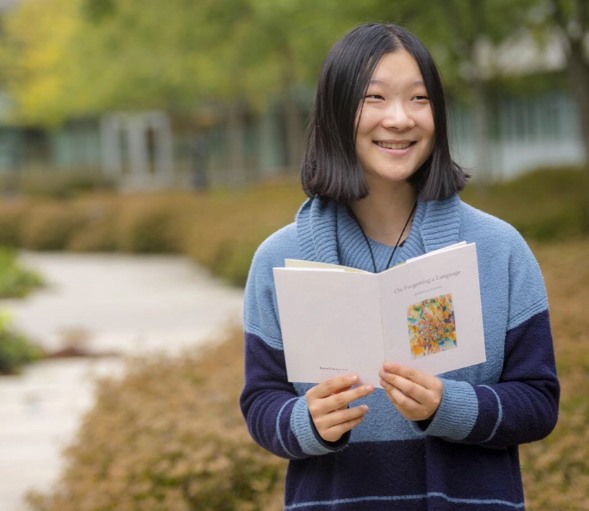

Now age 19, Isabella has been published in over 20 journals, including Prairie Fire, The Fiddlehead, Arc Poetry Magazine, Contemporary Verse 2, The /tƐmz/ Review, and Looseleaf Magazine. Her autobiographical piece “Rain Clouds,” was published in Issue 154 of The New Quarterly; “Shortcomings of a Juvenile” in Issue 146. The latter was shortlisted for TNQ’s 2018 Edna Staebler Personal Essay Contest when Isabella was 18—the youngest writer shortlisted for the contest in TNQ history. Isabella has also received a Pushcart Prize nomination for poetry and has been shortlisted for both the Minola Review Inaugural Poetry Contest and the Malahat Review’s Far Horizons Poetry Contest. Her debut poetry chapbook On Forgetting a Language, published by Baseline Press in 2019, has entered its third printing. Her new, full-length poetry collection Pebble Swing is forthcoming in Fall 2021 from Nightwood Editions.

Writers from J.R.R. Tolkien (The Lord of the Rings) to Gillian Flynn (Gone Girl) studied at post-secondary institutions before writing the quintessential works of their careers while some, like Harper Lee (To Kill a Mockingbird), dropped out before earning a degree. Many avoided university altogether and developed their craft independently. These pathways point aspiring authors and poets in opposing directions, making many unsure of how to start their careers. Isabella Wang proves to be a unique case study in following two paths at once, as she is working towards earning a degree in writing while working as a writer. Does she view her education as a pathway to her career goals? We spoke in a video conference about the connections—or disconnections—between her writing career and her literary education.

What factors impacted your decision to start working as well as attend university?

I had no other choice; because of my family circumstances, I was working through child welfare for a while and was largely on my own by the end of high school. The only money I had when I left home was a $250 cheque from TNQ—my first income ever sourced from writing. All the money I made that summer I invested in my tuition, not knowing if I would be able to afford the next payment the following semester. I was homeless most of my first year and “lived off the land” at my university, so to speak, in order to pursue my studies and write at the same time. I was taking a full-time degree and working four to five jobs aside from my creative writing gigs and writing conference papers. I was lucky that a lot of my jobs were writing related so I was doing what I loved, but it was a lot.

What is the value you have found in diving into a job in the writing business like writing for Room Magazine?

Room is one of my favourite jobs. I started out as a volunteer. I was in my last year of high school, just beginning to write seriously, when I saw an ad for a literary festival run by Room Magazine in Vancouver. I wanted to be a part of it so bad that I volunteered 30 hours over the course of three days. To me, that was just a way of getting involved and being excited—later on I was told that some of the festival organizers were shocked to learn Room even had 30 hours of events. But it was the greatest weekend of my life; I got to meet so many writers and many have become some of my closest friends and mentors.

Through that experience I got to know Room’s Publisher, Meghan Bell, and Managing Editor, Chelene Knight. When I was starting university and needed money, Room helped me by hiring me as an intern. The skills I picked up over those few months, from grant writing, to shadow editing an issue of the magazine, to administrative, behind-the-scenes work that keeps a literary journal running, were invaluable. I was also invited to be on the programming committee for the literary festival that year. I acted as Youth Programming Consultant, in charge of organizing and hosting the Youth Reading. In the past year I have also worked as Room’s Submissions Coordinator, and I’m now temporarily the Web Content Coordinator. In the fall, I will also be the Editor for Issue 44.2 of the magazine, working with assistant and shadow editors, Micah Kj and lue Boileau. Room has been great to me. They have been a lifeline when I needed them. We are also a collective so I am always meeting new Roomies.

Are there any unexpected lessons about writing you learned in university?

Two semesters into my university degree I was granted permission to take a fourth-year poetry class taught by Dr. Stephen Collis with a focus on BC poets: Phyllis Webb, Fred Wah, and Jordan Abel. One of the sections we studied was a series of ghazals written by Phyllis Webb; a Persian form of poetry originating in 10th century Iran. Webb had transgressed beyond the rules of the form, riffed off ghazal writers that came before her, and innovated the form in her own unique way. I think what provoked my interest in this collection was how difficult it was to understand what Webb was doing.

I began researching Canadian poets such as John Thompson; poets that Webb herself had cited, who had done similar work with the ghazal. That led me into a completely new direction, for I was not only studying English, but World Literature as well. When I took the form beyond its purely Canadian context I discovered there were a lot of female Farsi and Urdu poets writing in the 20th and 21st centuries challenging the strictures of the form. I realized that what I was studying was not just one very recognized Canadian poet breaking the form of poetry from another culture, but more of a phenomenon: a community of poets working with the form, performing through breakage of—a kind of refusal to be held back by the patriarchal roots of the form. I have wanted to pursue this project ever since, and Dr. Collis from my English studies as well as Dr. Mark Deggan from World Literature, have both been very supportive of me.

This obsession started in class; we were discussing 20 poems by Phyllis Webb, and the next day I said to Dr. Deggan: “Guess what I found? There’s a collection of Urdu poems at the National Archives in Pakistan!” He looked at me and said: “Isabella, we’re not going to Pakistan.”

What is the value, personal or professional, you have found in your literature classes?

The academic has aided my literary work, which involves writing, reading, editing and interacting with other writers at festivals and events. When I first joined the community, there were dynamics that I was being exposed to that were both eye-opening and overwhelming. As someone who wanted to pursue a career as a writer, I began to realize that writing doesn’t just entail me sitting at home; there is a lot of social responsibility tied to it. In this sense, university has helped me to understand our current social and political world. It has been a place where I can ask questions and learn from my mistakes. It has offered me a set of lenses that I would not have gained any other way—for instance, feminist criticism, postcolonial criticism, or lesbian, gay and queer criticism. And it is often in university that I read theory as a way of understanding the global situation that we live in. It is through writing, however, by working and engaging with other writers and their work, that I begin to see the soul inserted back into the theory. I see what I read being enacted in real life, with a human heart and pulse. That is what is most important to me.

The current Phyllis Webb project is an example of something I learned in university that has impacted my creative writing. After studying Webb’s ghazals I began to write ghazals myself, often writing through and in response to Webb and other poets. These ghazals are embedded throughout my current manuscript, with my last section entitled, “Thirteen Ghazals After Phyllis Webb.” When you factor in the equation of translations—reading poems by women ghazal writers in Persian, Farsi, Urdu—I am learning a lot about translation theory in school and applying that to my own work as well. I am also writing about appropriation: what happens when you take a cultural form that has been integrated into ceremony and song from one culture and express it through your own voice in another Western culture. This exchange can be a process, with writers expressing themselves and influencing each other, but also can be problematic. It’s an intricate project requiring a lot of time, and I’m building on my creative work as my academic perspectives evolve.

Does what you learn in your classes help you with the writing you submit to journals?

By studying literature, I have learned so much about the poetic form, different styles of writing, and theory that I constantly embed in the writing I submit to journals. I have also taken a few creative writing classes which I think are important to any writer who is looking for mentorship and getting started, because you get the opportunity to explore your own voice, and you get amazing feedback. It’s not only in a workshop environment, but also when I’m working with an editor. I’m always learning something new about myself and my writing, which is so useful when you’re building your craft and looking to submit.

I personally take one or two creative writing classes a year, so most of the time I am writing aside from work and academics. When there is a grade and a deadline attached to the writing it’s different. It’s not exactly how writing functions in the real world when you’re submitting to magazines and journals, taking months to write something and then another few months to edit it. So I think there’s a benefit, but you can’t depend on that alone.

How important is it to have good professors to propel a writer forward in their interests, as opposed to having professors who may dispirit a student from learning more?

I think it is important to have good mentors and professors at every stage of a writer’s career, but especially when you’re an emerging writer who loves to write and doesn’t have a lot of confidence. It can mean the world to have someone believe in your work and tell you that your voice means something. When they’re giving you feedback, I often find that a little goes a long way.

I wanted to write in high school, but there weren’t a lot of programs in my school. I was too young to enrol in a university degree, so in Grade 12, I took a creative writing Continuing Studies program at SFU with local poets Fiona Lam, Evelyn Lau, and Rob Taylor, all of whom have been published in The New Quarterly. They were the most incredible people, and they taught me everything I needed to get started—not only the poetic form and how to write, but how to edit my own work. They exposed me to a lot of local poets and took me from the purely traditional mindset to a whole new genre of contemporary poets that I hadn’t heard of until that point. I think it takes a writer to be passionate and pursue that passion, but it also takes a mentor who has experience and is willing to support them.

When I was still in high school, I had published my first poem in a literary journal and I was going to literary events. Back then, I was afraid to call myself a poet because I thought I might offend other poets. It wasn’t until someone else introduced me as a poet that I said, “Oh yeah, maybe I am.” When you have someone recognize that and give you that space and support, it means a lot.

The connection between mentor and mentee goes both ways. I’ve had the pleasure of mentoring very talented youth writers and poets, and they have taught me so much. When you are pursuing writing as a career you have so many deadlines; you’re always submitting, getting acceptances and rejections, sometimes you can lose the bigger picture. I find working with them very restorative and hopeful. They’re energetic and passionate, and they remind you of why you went into this work in the first place.

Did you have any professors that helped you reach your writing goals?

All my professors at SFU have been amazing. The support wasn’t what I expected going into university. I was in a rough patch, and in high school they always tell you that professors are not going to baby you. It’s going to be an adult environment and you’re going to have to fend for yourself. So I went into university thinking that everything was just going to be a black and white exchange, not expecting any of the human connections that would come out of it. That said, I do think that I was in somewhat of an interesting position thanks to TNQ and the writing community. I was already involved in the literary scene going into university: working at Room as an intern and having already been published. Later, I was also presenting at graduate conferences. These were all opportunities that I was given by the kindness of my community and mentors, and opportunities that I had to work for. I was also told that it’s very rare for an undergraduate student to be doing all that at my age. I had to set my own expectations. And once they saw how passionate I was about my writing, my work, and the people in my life, my professors Dr. Stephen Collis, Dr. Diana Solomon, Dr. Clint Burnham, Dr. Mark Deggan, and Dr. Melek Ortabasi supported me 100 percent of the way. They’ve motivated me and pushed me with their expectations, and at the same time they always made time for me when they knew that I was struggling, always being sure to check in to make sure I was taking care of myself.

How important for one’s writing career is getting involved with their local writing scene? For instance, did getting involved with Vancouver’s writing scene further your career?

Definitely. I know some writers whose day jobs are separate from their personal lives and their writing, but for me writing has always been everything. In my first year I was just going to workshops and developing my own voice, and it wasn’t until my mentors began introducing me to events, and I got social media that I began to grow acquainted with this whole community.

It started out with one writer, Kevin Spenst, who reached out to me at a reading and, even though I didn’t know anyone, said, “Next week I’m going to be reading at this place; there’s an open mic, do you want to go?” And by going there you meet another ten people. With every reading you meet new people, and by the end of it you’ve at least heard of most writers in Canada. That has been incredible because there is something special about reading someone’s work when you know them as a person—when you know their life, when you know their dogs!

I was learning so much when I was reading other people’s work and getting to know not only the literary world that occurs inside a text, but the conditions and dynamics that shape the literary world. I’ve met all my closest friends through the literary community—it’s everything to me.

Do you think writing is a social pursuit? A lot of people historically have said that writing is solitary because you do it alone, but for instance, is the path to becoming a writer necessarily intertwined with other writers?

I know what you mean. I had a writing mentor in university who said that writing is a solitary act, that writing is lonely, and that you need a lot of stamina just to push through. And even though I admire him a lot, I do not fully agree. Aside from the literary readings and social gatherings I’ve talked about, writing is always a connection and a transaction. Even when I’m writing at home and not going to readings I’m still responding a lot to writers in my own writing. It takes a lot of energy, emotions and effort for a writer to channel the strength to produce an essay, a poem, or a book. Once out there, it takes another acting force for that body of work to be picked up, read and responded to. When you create that kind of dynamic between writer, reader, and text, it creates what I like to call a form of ecology. When we think of ‘ecology,’ we think of the interconnectedness of organisms, but it’s also very present in writing. When a writer is taking the time to create, they are not only replicating some form of the social dynamics that govern the real world, but also imagining alternative worlds. Literary critic Pheng Cheah calls writing a “world-making activity” in progress. When one writes, when one reads, that process is ecological, and it is a natural interaction.

What do you think have been the best takeaways from working with other writers? For example gaining mentors, expanding your own ideas of what it is to be a writer or, as you just mentioned, how you respond to others’ writing?

There’s so much and I’m constantly learning, so I’m going to talk about some of the best advice I’ve ever gotten – from Wayde Compton – that has really helped me. He was acting as director of The Writer’s Studio at the time. When I published one of my first essays on Learn Writing Essentials, an online writing and mentorship program founded by Chelene Knight, he responded with a really nice letter. In the letter, he told me, “You will learn that your writing is best when you do not pander. When you follow your own interests no matter how strange or obscure you suspect they might seem to others. Others will in fact connect with your writing, especially when you go deeply into your own particularities.” His words have had a profound impact on my entire writing experience. I return to his words all the time, before readings, when I’m feeling dejected, when I’m chasing obscure interests and thinking, “Are others going to care? Are others going to respond? Because this is weird.” But my best writing comes from times when I’m just being myself and not trying to be overtly clever.

As Isabella and I finish video chatting, I am left feeling revitalized. Just how she described mentoring young writers as restorative and hopeful, Isabella herself has, as she said, reminded me of why I went into this work in the first place. Isabella and I have led incredibly different lives and come to the same conclusion: we want to write. I can see myself in her writing, like I saw myself in the first books I learned to read, because stories show us ourselves in others no matter how different they may at first appear. Her commitment to learning propelled her to personal and professional success while overcoming many barriers. The inspiration that emerging writers should take from Isabella is her tenacity for doing what she loves, and taking every opportunity to do it.

You can follow Isabella’s adventures writing, reading, studying, taking care of her cat and supporting great authors on Twitter and Instagram @isabellawangbc and on her website at isabellawangbc.weebly.com.