The Long Route to Le Mas Blanc: A writing retreat in the South of France

This piece was originally posted to the TNQ blog in Spring 2013.

I am a terrible traveller. Pretty much phobic about flying. Ironically, I’ve spent my life travelling. I was born on an overseas business trip—crossed oceans and continents my entire life. I should be cavalier but I’m not. Quite the opposite. My fears were intensified by a series of horrible incidents on planes: fires, forced emergency landings, violent passengers, and a miscarriage en route from Australia to Fiji. I was the one miscarrying, doubled over in the tiny toilet cubicle, gripped with pain and fear and sorrow, and blaming myself for flying pregnant.

I had all but abandoned flying when I happened upon an article about the Yorkshire-born travel writer, Bruce Chatwin, who apparently travelled to the far reaches of the globe with little other than a rucksack full of prescription drugs.

I’ve long regarded Chatwin as an ally. Yorkshire is also my ancestral home. I admire Chatwin’s dogged determination. And I’d heard him described as so gay he was positively festive. I feel instinctively I would have loved this feisty, festive man. But it was his rucksack full of medications that helped ease my fear of flying; the realization that anxiety is part of travel even for the most intrepid. And the simultaneous insight that there’s a drug for that.

So, in a heated moment after looking at the Air France website daily for two weeks, I belted back a stiff drink, reminded myself how much I love France and paid for a non-refundable trip across the Atlantic. My mission—a writing retreat in the South of France. I was going to stay in an old barn, the solo writing retreat at Le Mas Blanc, home of Canadian writer and French resident, Isabel Huggan.

On the train between Kingston and Montreal’s Trudeau airport, I let go of the pre-trip chaos and shift into another mode altogether. I order coffee and watch the bare, brown fields go by. It is early April and the snow is gone, but it is still the limbo land between winter and spring.

I cross the Atlantic with two seats to myself. I order champagne. I watch movies instead of sleeping. The Ativan in my carry-on goes untouched. In Paris, I charge between Charles de Gaulle and Orly airports feeling almost worldly, with minutes to spare before the final leg of my trip.

Isabel Huggan meets me at Montpelier airport. She is lively, has a great smile. Her car has recently sustained some damage. “It’s kind of rakish, driving a slightly banged-up Citroen,” she says.

Moments later we are hurtling along narrow French roads—two women, footloose and schedule-free in the beautiful South of France, in the rakish Citroen.

I’d read about Le Mas Blanc in Huggan’s award-winning book, Belonging, never once imagining that I might one day visit. As we pull onto the property, remnant details of the book come flooding back: the ancient bridge, the olive trees, the old micocoulier tree on the terrace overlooking the river, the stone house and barn that will be my home for the next two weeks.

The barn doors are epic. Huge. Handsome. Solid wood. Beside the barn is the river, behind are the garden and orchard. In front of me is Le Mas Blanc. Outside my second-floor studio windows, the beautiful grey-blue Cevennes Mountains.

It’s cold and damp, and utterly rural. Surrounded as I am by stone and river, I feel as close to my heritage here as I would in Yorkshire. I am, strangely, home. A sense of belonging.

Routine sets up quickly. I write all day long, taking time out to walk and eat. Walks usually take me along the river across the ancient bridge, past the vineyards and the 12th Century Romanesque church. There is a perfect hilly walk through the old village and other options for more remote walks, but I prefer to avoid the wild boars so I stick mainly to the paths I know.

The first week is unseasonably cold. I write with a hot water bottle, hot tea, a blanket draped over my shoulders.

This is the perfect place to write. Distraction-free. No café or corner store. The village has only a post office and French library. My studio is equipped with breakfast and lunch fixings. Initially I eat too much. Isabel has laid in: tapenade, cheese, chocolate, honey, biscuits, fruit, muesli, yogourt. I make deals with myself–I must write another page before I eat another piece of cheese.

At night I head over to Le Mas Blanc for dinner with Isabel. We talk about food, cooking, writing, books, France, travel, and eventually, about life and love and lovers. Some nights Isabel lets me loose in her kitchen. I cook while she lights the fire and sets the table. These nights are a highlight; the fresh wild leek omelette seared into my memory forever.

I knew when I read Belonging that Isabel and I share a love of place—a love as potent and meaningful as any other. The love of place is as much about longing as anything else—the beautiful yearning aching for somewhere or something left behind.

Week two, and the weather warms. The frogs in the river start their croaking. I lay in bed at night, listening—smiling to myself. The frogs of France are keeping me awake… Isabel tells me that the almighty racket they are making is the sound of their mating. Who can be lonely with that for company? I drift off every night to the sound of frogs making love.

Daily walks through the vineyards bring glimpses of the first tendrils of life appearing on the ancient vines. Asparagus and strawberries are in season. I turn off the heater, shed my blanket and hot water bottle and return to my desk—my notes—my computer. I keep writing. In my second week it feels as though I mustn’t stop. I am conscious that my time in France is running out. This is the ultimate luxury—this absolute quiet—this much time to write, this freedom from work and chores.

Isabel convinces me to see a little of the Languedoc-Roussillon, the largest wine-growing region in France. Grapes have grown here since the Pleistocene era, since before the appearance of man. Grapes actually preceded us.

We visit the neighbouring towns of Anduze, St. Hippo, Nimes, and Uzès. I am smitten with everything.

In medieval Uzès, a town famous for its beauty and history, we walk the narrow curving cobblestone streets, admiring the tile roofs, the wrought iron, the faded, ancient shutters, the French blue, and the remnants of ancient history. The Romans built an aqueduct in Uzès in the first century BC to take water to nearby Nîmes; this town is over two thousand years old. In Kingston, where I live, we are proud of our two hundred-year-old buildings, of our history that reaches back to a time before Canada was yet a country.

At the market in Uzès I buy local olive oil in a sleek black tin, an olive wood cutting board, and a fabulous, huge (and very French) sac au main. Isabel buys artichokes and fresh pasta and sun-dried tomatoes as plump as fresh plums. We sit on a café terrasse enjoying coffee and pain au chocolat. The sky is brilliant blue, the deep cornflower blue of neighbouring Provence. The plane trees are just beginning to bud. Locals walk by, their market bags brimming with flowers and baguettes.

On my last night in France, I sleep badly, dreaming about not waking up in time, missing my flights. I check my clock and listen to the dark night, repeating the dream-wake-clock cycle over and over. I think about my time in this old barn in the South of France where I have been steeping in history and culture and fresh air. I have been living on cheese, honey, coffee, wine, listening to love-making frogs.

I waken to the alarm jangling. Sunshine is pouring in the windows. Isabel and I are back in the Citroën, hurtling along the now familiar narrow roads, heading towards the Mediterranean, to the airport in Montpellier.

There is a strange power in repositioning oneself. It is not just the time and space that a writing retreat affords, it is the explosion of neuronal activity that jolts one into the miraculous state of being fully alive. As Henry David Thoreau wrote, “It matters not where or how far you travel…but how much alive you are.”

I would like to thank both the Ontario Arts Council for the International Writing Residency Grant that enabled me to travel to France to work on a series of stories about transgender journeys; and Isabel Huggan for her care during my stay at Le Mas Blanc.

For more information about Le Mas Blanc, please visit: http://www.isabelhuggan.com/.

Delectable, down-to-earth recipes to see you through your retreat are posted on Lindy’s blog, “love in the kitchen” at: http://lindymechefske.com.

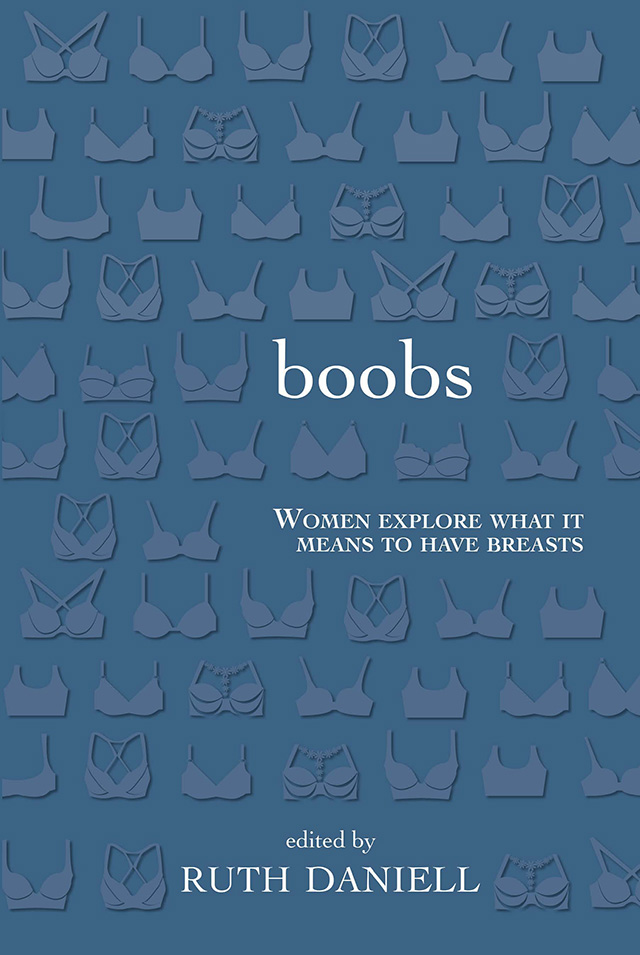

You use the phrase “their uncommon bodies” to describe the cranes (“sure-headed mystics adorned with nuptial red”). That puts me in mind of another of your projects, one you both conceived and edited: the anthology Boobs: Women Explore What It Means to Have Breasts. The publisher (Caitlin Press) describes it thus: “At turns heartbreaking and hilarious, Boobs is a diverse collection of stories about the burdens, expectations and pleasures of having breasts. From the agony of puberty and angst of adolescence to the anxiety of aging, these stories and poems go beyond the usual images of breasts found in fashion magazines and movie posters, instead offering dynamic and honest portraits of desire, acceptance and the desire for acceptance.” I like that last pairing. Can you tell us something of how that anthology came together, of the way the poems and stories (essays too?), as they came in, surprised or unsettled you?

You use the phrase “their uncommon bodies” to describe the cranes (“sure-headed mystics adorned with nuptial red”). That puts me in mind of another of your projects, one you both conceived and edited: the anthology Boobs: Women Explore What It Means to Have Breasts. The publisher (Caitlin Press) describes it thus: “At turns heartbreaking and hilarious, Boobs is a diverse collection of stories about the burdens, expectations and pleasures of having breasts. From the agony of puberty and angst of adolescence to the anxiety of aging, these stories and poems go beyond the usual images of breasts found in fashion magazines and movie posters, instead offering dynamic and honest portraits of desire, acceptance and the desire for acceptance.” I like that last pairing. Can you tell us something of how that anthology came together, of the way the poems and stories (essays too?), as they came in, surprised or unsettled you?