Rejections were barely whispered in our writing group. A few of us shared details at times in a text, an email, but never to the whole group and rarely face to face. Then in 2017 TNQ editors Pamela Mulloy and Susan Scott asked us to write about rejection collectively. At the time, we—Jagtar, Tamara, and Leonarda—were working with TNQ on diversity and equity issues and when the editors came to meet with our writing group, we got talking about rejection, the process of rejection. Not just how it felt, but where and how rejection lands. We wanted a chance to share how rejection lives in our bodies and how we move through it both individually and collectively as writers.

We wanted to speak up, to editors. We want editors to listen.

Our group has been together for three years now. We first met in a creative nonfiction class and, one class turned into more classes, and then writing group sessions. We gather in each other’s homes on Saturday mornings. We are a group of nine.

In our group, we share the most intimate details of our lives, yet before we had embarked on this project with TNQ we had not really spoken to each other about the rejection letters we receive and the impact that some words, or silences, have on us and on our writing. The way rejection cuts through us, and into us. Even though all of us had experienced rejection, for some, it was like our dirty secret. Those brave souls who were willing to mention it briefly did so over our morning coffee, cheese balls, and crackers before we moved onto the real work of workshopping our pieces.

Of course, each of us experiences rejection differently. We come from different locations. Our writing group is diverse and we write about experiences that are often not represented in CanLit. We write about personal trauma and family trauma, intersecting race, sexuality, and aging. We write about migration and feeling like an outsider and out of place, we write of loneliness and wanting, and ugliness. We write about shame and unlikeable female narrators. Our work doesn’t always find a home. Can we ever be home if we are not invited in? What happens if some cross the threshold while others are left behind?

Writing about rejection, and sharing it openly with the group, has allowed us talk openly about pain, about the ways we move through rejection individually and collectively, and it has allowed us to learn how to support each other on this journey.

This note, by one of our group members, Emily McKibbon, is in response to a rejection letter. We include it here because it is written beautifully and because it encapsulates the ways that rejection is held and responded to collectively:

There’s something really inherently gritty about you—all of the things that you think make you less of a success are really all of the things that show how inherently tough you are. Rejections are the worst, but I think the secret is just being super gritty. You’ve gotta be that girl in the horror movie with the knife in her teeth who’s climbing back into danger because she’s burnt out on running away from her troubles. That’s the girl that kills Jason. That’s what Mary Karr would do.

Along the way the lonely experience of rejection has become a group affair, our rejection emails continue to be shared as if we are showing our war wounds with pride. We are taking risks. Most importantly, we are a community. We are not alone.

—Leonarda Carranza with Jagtar Kaur Atwal and Tamara Jong

Perfection

“I don’t see many publications that represent who I am, or my experiences, so I wonder if anything I send for publication will ever be accepted.” I recall saying that or a variant of that in response to the question posed by TNQ about rejection.

There was more to that response.

It was the same reason I could not go and talk to Bisi as a twelve-year-old in the school cafeteria after Emeka told me to chat her up. Instead, I sat a number of tables away watching her. It was the same reason that, even as an adult, I could not go up to people I was attracted to and ask them out or talk about who I was attracted to with family, friends, and co-workers. It was also the same reason that I tried to hide my stutter.

Thinking about rejection made me recall another question I had to contemplate from time to time for many years during interviews.

“What are your weaknesses?” The answer I have given over the years—my illusion of strength—was, “I tend to always be perfect.” Recognizing that my name gives an indication of my race, I had always ensured I was overqualified for the jobs I pursued, in a sense perfect for those roles.

Being perfect, I came to realize after months of exploring my stutter, was code for “I don’t want to be rejected.” I felt stuttering was a stain that I could not wash off. So like the other things that I thought made me imperfect, I tried to hide it.

Perfection was the mask I wore. If I am so good, how could I be rejected? So I worked hard to be perfect, by hiding my stutter, by making sure I was overqualified for jobs, and by making sure potential partners were interested before I approached them.

In 2013, I began taking creative nonfiction writing classes. I have always considered myself a numbers’ person and made a living by analyzing financial data, but I kept returning to creative nonfiction, feeling compelled to tell my stories. Classes turned into a writing group, friends started sending out their work, and I felt the pressure; some encouraged me to send my work out too. But how could I? The pursuit of perfection seemed futile here. My work never felt perfect. How can I measure if my work is perfect when there aren’t many writers like me in CanLit to compare my work to? But also, if by some fate it gets accepted, how will readers receive it, what if people I know read it, what if people don’t like what they read about me? I have a piece I am working on that weaves in my struggles with race, sexuality, and my stutter. I say this is the one I will send out. But there are complicated risks in rejection. Will I send it out? I’d like to think so; I’d like to think I will embrace the possibility of rejection.

~Obim

Minefield

We appreciate the chance to read your piece. Unfortunately it’s not for us.

My eyes dart across these words, sprinting from one to the next. I barely pause at one before I’m off again. I’m scared to slow down; I keep running and running, through the minefield of letters, until I get safely to the end. Then, Kaboom! The meaning of the sentence explodes in my brain.

Another rejection.

Another rejection.

Another rejection.

Sigh. Well, fuck you. My first thought is directed to the editor, to whoever sent me the email, to whoever the contest judge was, to whoever the readers were, and to whoever else might have been involved. Who are they and what do they know? I conjure up pieces of my piece, rolling the words and images around in my brain. They’re etched there, a testament to the amount of time and effort spent on their creation. They’re good.

Aren’t they?

Hemingway has been quoted as saying, “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” This holds a particular truth for creative nonfiction writers, as the craft is founded on personal truths. We reach deep inside ourselves, gather the silent, the untold, the most meaningful parts of us, wrap them up in a ball of words and lay them out on the page and say “Here I am.”

And they respond, “No.”

NO. We do not accept this. We do not accept YOU. This is what I hear in my mind when I read a rejection letter. There’s a reason rejection hurts. MRI studies tell us that the brain responds to emotional pain and physical pain in similar ways. When you’re rejected socially, the same areas of your brain become activated as when you’re, say, punched in the gut. Which is sometimes what reading these rejection letters feels like.

I look at the rejection again. Whereas before I tried to run past the words without actually reading them, now I turn to each and every one, individually, and hold them up to the light to examine closely. Trying to understand what I did wrong and why I wasn’t chosen.

I shrink, deflated. Thoughts cascade and push me down. My piece sucks. I chose the wrong theme. I chose the wrong words. They didn’t like it. I’m not good at writing. I’m not good at this. I’m not good. I shouldn’t bother anymore.

And while other rational thoughts try to bubble up, right now they don’t hold weight. For example, the understanding that my piece could have been rejected for a number of reasons beyond I suck. Right now, I want to wallow in self-pity. I want to scowl, and hate. Until I’m ready to remember that this does not define me, and I’m ready to pick up the pen again.

~Lina

Stats

Thanks for the invitation to rant about my rejection history. I’m hoping it will do me some good, since a couple of burning rejections in March seem to have almost paralyzed both my writing and submitting practice (to the point where I spent a week sprucing up an essay I’ve been writing for a couple of years, and as I was about to submit it, I suddenly felt it was complete crap, and as a result didn’t submit it to the Event contest, and then froze in the same way at 11 p.m. the night of the deadline for the TNQ contest.

First some statistics:

I’ve been submitting since 2013. According to my records, I’ve made 158 submissions in these four years. In all, 108 have been rejected, 40 I withdrew of my own accord—some because I lost my nerve, some because I submitted simultaneously and the piece was accepted elsewhere. Only ten have been accepted (and a couple by third-tier publications, so not much to write home about).

So rejection is a constant doctor’s hammer testing my reflexes.

Some anecdotes:

My worst, most impolite rejection came from Geist. A flash fiction story was rejected without even sending out a form rejection letter. No “We’re sorry to inform you…” Instead I got a system notification from Submittable that my submission had been moved from “in-progress” to “declined.”

I’ve collected five rejections from Malahat, and at this point almost use them as a vaccine to overcome my fear of rejection. With them it’s a certainty, the only question is how long it will take. Stuff they can’t stand is usually booted out by 25-27 days. None of my pieces has survived more than 30 days.

Some rejections I almost want to frame, because they made me feel worthy of those extra ten minutes.

The Boston Review sent me a short note with my rejection about my writing showing promise. Some lovely passages, they wrote. The rejection took so long I had already started to see gaps in the story, but the idea that Junot Diaz (fiction editor) had taken the time to add a line and a half helped me to keep going through the years I only got one piece published.

Boulevard sent me a wonderful evaluation of my piece, saying that several of their readers had really liked it, and then went on to discuss what worked and didn’t work according to the panel evaluating the piece. I’m still working on a story I think would fit their esthetic, and while I do the fifth edit I think of the fact that my name would be ahead of Joyce Carol Oates on the cover (in alphabetical order—she has a story in Boulevard 75 percent of the time), which is of course setting myself up for disaster and heartbreak. And still I can’t stop myself.

My latest lack of success revolves around a short story titled “Salt,” which has gotten personal, encouraging rejection letters all around, but which still hasn’t made it across the threshold. I thought I had made it when Upstreet (an annual anthology) kept the piece for close to six months on their short list. I was already imagining myself wrapping the book in Christmas paper and sending it off to my parents. The rejection (albeit personal and detailed) felt like being hit by a police baton: sudden, painful, and completely unjustified.

I got right back up and submitted the story again, this time to The Sun magazine. After all, it was a good story, everybody who’d read it said so.

A little more than a month later, the rejection letter read:

Dear Hege,

Thanks for sending us “Salt.” We’re sorry to say that it’s not right for The Sun. This isn’t a reflection on your writing. We pick perhaps one out of a hundred submissions, and the selection process is highly subjective, something of a mystery even to us. There’s no telling what we’ll fall in love with, what we’ll let get away. We rarely respond personally to submissions, as the number of manuscripts we receive makes this difficult. We’re aware that writing is hard work, and that writers merit some acknowledgment. This note doesn’t speak to that need. Please know, however, that we’ve read your work and appreciate your interest in the magazine…

And that was it. I’m still in the crawling state where every attempt to get up is crushed by the fear of being hit again. Who knows when I’ll get back to writing with confidence again?

~Hege

Classroom Lessons

I learn about rejection and shame in classrooms where I am often the only woman of colour. I learn to keep quiet and hide bits of my stories from other writers and educators. I learn to press my lips together and study white writers and their writing practices and styles. Their characters do not sound like the people I write about. When I submit my work for workshopping, I learn that my stories are strange. Sometimes, the stories elicit a visceral interest and excitement from the writers in the room. Sometimes they gawk at me. Sometimes they question the authenticity of the experience. “Did that really happen?” It feels too abnormal for them. It must not be completely true. I must be exaggerating the details. At times, I am red-faced from their interest. I feel like a strange animal. During and after class students take liberties with my work and ask me probing questions about traumatic events. They are eager to know all the details. And even though I am not ready to discuss these things for their interests, I am too young and too shy to set my boundaries. I learn to write and hide myself in these spaces. I begin to hide the parts that make me feel shameful.

In these writing spaces, educators rarely take an interest in my work, except to correct me or to mock my grammatical errors. The mistakes are so glaringly obvious that the classroom is invited to laugh along and enjoy them; as signs of my out-of-placeness. I feel visible and yet invisible at the same time. Some of the grammatical structures seem foreign to me. They are difficult for me to adopt. I want to write in the language that we speak at home, in the movement in and out of Spanish and English, but this is not proper, and the class reminds me that they are the readers and that they can’t be left out of my work. I want to write with the missing prepositions and the attempt to move between languages, but the readers are left with too many questions. They are not satisfied and I do not know how to navigate their dissatisfaction and unknowingness.

“Leonarda,” wrote one of my writing instructors, “Let me remind you that writing is about a relationship between the writer and the reader.” She does not realize that I do not trust her as my reader. That if she were to represent all readers I would never write my stories. I know that if I am to write towards her gaze then I won’t write about the experience of being racialized, of coming to Canada as a refugee, of trauma or violence.

I take these classroom learnings with me into my process of submission. I research carefully where there are people of colour listed as part of the editorial team. I look to see what kind of work they read, what they are interested in. There aren’t many places that are revealed in this process.

I convince myself that I am protecting myself from potential rejection that my work is too raw, too personal, that it might be too painful to receive a rejection letter. But if I’m honest, I’ll admit that these raw stories have already gone through a steady stream of subtle and overt forms of rejection. It takes me years to realize I am looking for a home for my work that doesn’t make me feel foreign and out of place, and that, way before the work can even enter into the process of workshopping and editing, way before I can even fathom the idea of sending out a piece for publication, I need a writing community that desperately wants to hear these stories, a writing community that has been craving these stories as badly as I have been wanting to set them down and craft them into stories.

~Leonarda

Emptiness

I spent over 30 years as a Jehovah’s Witness preacher. I started knocking on doors when I was two. Doors were shut more often than opened. My buffer against the constant rejection was always God. I told myself that He was the one they were rejecting; it wasn’t personal. I was the messenger, his faithful servant. I would not get offended or hurt, ever. Surprised perhaps, by the lack of interest in Jehovah’s message about His Kingdom, but I remained hopeful. That is how I approached my ministry. That is how I approached the shut doors. When I was in my twenties, this man told my preaching partner and me that we’d better leave now or it wouldn’t be pretty. We didn’t stick around to see what he meant.

I didn’t feel alone in this work since we closely followed Jesus’ model of companionship preaching, “He now summoned the Twelve and started sending them out two by two” (Mark 6:7). If the sheep were there, Jehovah would lead the way using his angels to guide us to them. We were less focused on the results since, “God is not unrighteous so as to forget your work and the love you showed for his name” (Hebrews 6:10). God knew we worked hard to get his message out and he would reward our efforts with blessings and everlasting rewards. I gave my youth and energy to preaching work and spreading the good news of His Kingdom. I put my writing aside for a time. I did not know back then where this would lead me.

Just before my thirty-second birthday, I tried to take my own life. Later, I tried to make sense of what happened and began writing about my experience in fiction. I kept writing this story, or versions of it, over and over, but it was clear that I did not have the creative freedom or religious distance in my headspace.

Six years later, I stopped knocking on doors and slowly became what’s called an inactive Jehovah’s Witness. I no longer could give witness to a God I had lost faith in. I had become depressed again and started therapy with a Jungian analyst. She said she could not make any promises that I would still be a Witness when we were done. I decided to go back to my fiction and submitted it to the Humber School for Writers Summer Workshop. I felt hope when they accepted me and the story. For the first time in my life, I was really ready to dig in.

The story moved along a little, but it rang false to me. When a magazine did a call out for a special mental health topic, I felt that I could write the story the way it was meant to be written, nonfiction. Seventeen years seemed like enough space between me and what had happened. The story was rejected; the response seemed robotic, “Thank you for sending us, ‘Your Terrible Story’. We appreciate the chance to read it. Unfortunately, the piece is not for us.” How long had I preached and remained undaunted. I had hidden behind God as my protector and now I realized that I was alone. They weren’t rejecting God, only me. I had been sending out pieces for years and this was the first time that my heart hurt. I had shared something deeply personal so all the terrible things I thought about myself bubbled to the surface. I didn’t want to write anymore. I wanted to leave it. Maybe forever or temporarily. I didn’t know. I wondered why I would ever subject myself to rejection.

I stopped writing. Months passed. Stories didn’t come to me. If they tried, I shooed them away. I didn’t take notes, as was my practice. I could stop writing; my day job paid my bills, I reasoned, not my words. No one wanted them. Not even me.

~Tamara

Notice of Failure

I don’t have to wait for the mail to arrive to receive the dreaded letter of rejection. My rejections are tucked into my mind, and lie in wait each morning. The notice of failure is unfolding even now, as I write this.

I fidget. I search the fridge, clean the kitchen, surf the internet—anything to distract me from this certain rejection.

Some days I trick myself into really good writing. The process feels right, I am pleased, even excited. On those days, I am, indeed, a writer.

Then my writing abilities abandon me and I am left, bereft, with awkward phrases, way too much telling, not nearly enough showing. Lumpy dialogue. Shame.

Failure, fear of rejection created a hollow footprint in my early life. My father was quietly disappointed in my school performance. He thought I was lazy. My mother was convinced that I was smart, but “an underachiever.” In addition to my own hopes and humiliations, I have both parents’ voices in my head. Even now, as I enter my seventh decade.

The struggle often exhausts me, robbing me of my optimism for days on end. Then, for reasons that elude me, I find my own spark and take the risks that await. Most often, I stumble between the lure of failure and the waiting pleasures of words that flow, dreams that sing.

I sometimes take safe risks with selected readers. Our writing group receives the 27th draft of an uncertain effort. I share the work with carefully selected friends and my partner, himself a recovering writer. They rarely send letters of rejection. Instead they offer suggestions, encouragement, all to replace the condemnation of my dissatisfied parents who, long dead, live on in my writing heart.

~Laura

Retreat

When I was twenty-three, I gathered my poems and sent them to three different Norwegian publishers. The manuscript was typewritten, with typos erased with White Out, and then corrected with a black pen.

I had been writing for a while, on and off since adolescence, and the eighty-some pages were the culmination of two years of solitary work. I finally felt ready to have somebody competent read them, somebody who would see the real me and like me for my ability to string words together.

I wasn’t a very likable child. I was timid, but once I let down my guard, I suddenly suffered from galloping foot-in-mouth disease. I wasn’t stupid, though. As soon as I realized what I had said, I’d retreat to myself and my books. The botched conversations would play over and over in my head, and I’d think of a hundred things I could have said that would have made more sense.

In my poetry I was able to get the words right, I could edit and rewrite until it was there on paper—my better self: thoughtful, elegant, terse and just a touch vulnerable. A couple of months passed before the rejection letters arrived. There were no nasty letters, no standard rejections. Every single one contained some suggestion for how to improve my writing, weighed the strong and the weak points, and encouraged me to continue. I was devastated. The part of the collection I felt was the best, where I felt I had bared myself the most, were deemed too “hermetic,” unclear, which was editor-speak for “don’t know what the hell you’re saying here.”

I tried to go back to the poems, but the more I looked at them, the more lifeless they felt. I waited for the hurt to pass, waited for inspiration, but didn’t write another poem for more than twenty years.

So I abandoned writing, took on this new identity of someone who used to write, and ha-ha isn’t that funny.

It took me over twenty years to get back to writing. By this time, I had a husband and two daughters, I was entering the mid-life section of life, and I was writing in English. My ambitions were lower, I told myself. Even if I didn’t succeed in my writing, I had a life, I had a profession; it wouldn’t affect me as much now.

But even now, with close to a dozen publications, when the emails arrive, I’m still back there, in that cluttered student flat in my early twenties, completely exposed to someone else’s judgment. What was I thinking? I imagine someone who really knows English reading my work, seeing nothing but a word salad. And even if the words make sense, who’s interested in the thoughts of a middle-aged woman from Norway?

~Hege

Exposure (a few thoughts on taking it personally)

Sometimes a work leaves you exposed. In this case, rejection is not like a nightmare, it is a nightmare: it’s that one where you’re naked, and everyone is bored with and ignoring you. But here you should allow that you’re one of a panel of naked and exposed people, and take heart if you’re the most abject of these. There’s a glory in writing down to the bone.

Rejection is one thing. Failures of moral courage are another.

Lately I am looking for writing as ugly as my feelings.[1] Hot stories about shame, envy or irritation, written too soon and too quickly and too burnt-up to like easily. Unlikeable female narrators. Sweaty concepts.[2] Writers can be accused of failures of moral courage when they fail to write what scares them. Editors can be accused of failures of moral courage when they fail to publish what scares them. Writing is not something that languid aesthetes doddle with on a drizzly Tuesday afternoon. It’s fucking torture and we should acknowledge it as such.

I don’t trust writers who enjoy writing. I trust writers who write despite writing.

Which is not to say that writing is not necessary. But it’s work, and most of it’s dreary. The challenge is letting writing be necessary on its own terms, and acceptance be the extraneous, superfluous thing.

***

Confession: I am not sure how to let acceptance be the extraneous, superfluous thing.

I am particularly unsure of how to let acceptance be the extraneous, superfluous thing when I am writing my truest, ugliest self.

***

Can I tell you how much I love the ones who take it personally, who’ve got skin in the game?

I love these writers—and editors—by reading them. I read them because reading is a never-ending, grinding hunger. I read them because I believe we can become the audience we haven’t found yet. My proximity to several of these unruly new writers—Jagtar Kaur Atwal, Lina Barkas, Logan Broeckaert, Leonarda Carranza, Hege Jakobsen Lepri, Tamara Jong, Obim Okongwu, Laura Sky—makes me a better writer. (Tritely: makes me want to be a better writer.) To be naked and vulnerable in the presence of those you trust, and to emerge unscathed, is a specific kind of honour. I wear it like armour. I wear it like unassailability, in the hopes that it will soon feel as natural as skin. “No matter how dispassionate or large a vision of the world a woman formulates, whenever it includes her own experience and emotion, the telescope’s turned back on her. Because emotion’s just so terrifying the world refuses to believe that it can be pursued as discipline, as form.” (Chris Kraus, I Love Dick)

~Emily

Dear Jagtar

I understand that rejection confuses you, not because you don’t understand what it is or what it feels like but because you feel the pressure to be still in that space, when you don’t want to be.

You are not afraid. I know you know that rejection can play cruel games on the mind and the body, but you made a decision as a writer to accept that rejection comes along with this profession. When you first started to write, the thought of rejection weighed heavily on you; it’s different now. You are growing as a writer, becoming comfortable in the skin of a writer. At the beginning you could easily have walked away from it all, believing you were not good enough.

But something magical has happened along the way, you found something you can never let go of, and this feeling has a stronger hold on you than rejection could ever have. Writing is teaching you to understand who you are. Writing has been showing you how to love yourself. Writing is helping you to feel real. So keep moving forward at your own pace and follow the words because they will take you somewhere unimaginable.

~Jagtar

[1] Ugly feelings c/o Sianne Ngai, http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674024090

[2] Sweaty concepts c/o Sara Ahmed, https://feministkilljoys.com/2014/02/22/sweaty-concepts/

Jagtar Kaur Atwal resides in Cambridge, ON, and enjoys painting and photography.

Lina Barkas is a writer, psychological associate, and soon-to-be sleep-deprived mother-of-two.

Leonarda Carranza is a Central American born writer, raised in Toronto, currently resides in Brampton.

Hege Jakobsen Lepri was born in Norway, married in Italy and currently lives in Toronto, where she works as a translator and writer.

Tamara Jong is a Montreal-born mixed race writer currently enrolled in The Writer’s Studio.

Emily McKibbon is a Hamilton-born, Barrie-based curator and writer.

Obim Okongwu is a social impact consultant and writer, formerly a risk manager in the corporate finance sector.

Laura Sky is a documentary filmmaker, writer and researcher.

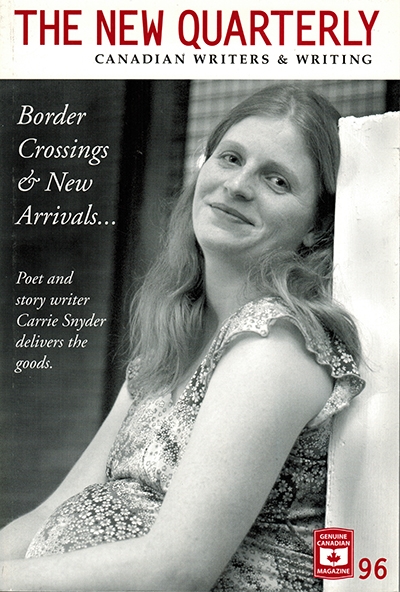

In 2005, I was featured as the cover girl, massively pregnant with my third child, an issue that also featured a story, several poems, and an interview with the magnificent Charlene Diehl, who had been one of my profs in university.

In 2005, I was featured as the cover girl, massively pregnant with my third child, an issue that also featured a story, several poems, and an interview with the magnificent Charlene Diehl, who had been one of my profs in university.