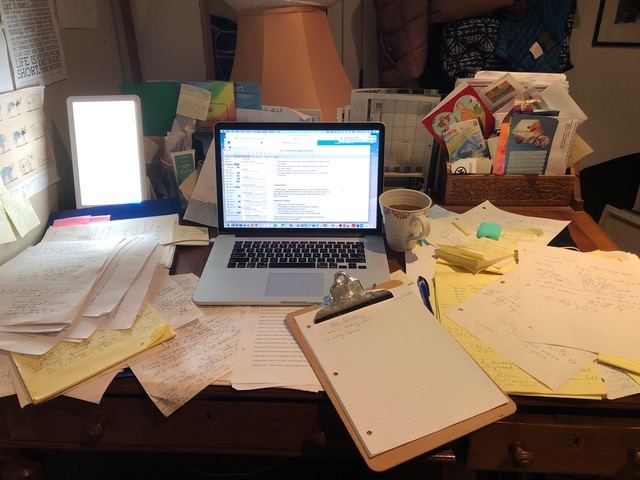

What is Heather Paul Reading?

My reading life is typical of the rest of my life: always a lot going on. I usually have three to four books on the go, one of which will be an audiobook. Often the audiobooks will be nonfiction, usually in the realm of health and wellness, food and drink. Recent non-fiction reads (approximately two per month) have included Gabor Mate’s, When the Body Says No, and Anodea Judith’s, Eastern Body, Western Mind. As I am also a yoga teacher, I find the connection between the mind, body, and spirit, inspiring and fascinating; and, I am able to enjoy learning while performing mundane adulting or exercising.

In terms of actual reading, like fiction on paper, I always have several books scattered throughout the house. As I like to say: one for fun; one for challenge; and one for book club. Right now, my fun read is Judy Blume’s, In the Unlikely Event. I selected this title because I had never read any of her adult novels, but one of my most memorable Christmases as a child was receiving a box set of Judy Blume books which I tore through, read in about a week, and proceeded to read over and over again. I still remember the trial scene in Blubber, Shelia the Great’s swim test, Deenie’s scoliosis brace, and have enjoyed rereading the Fudge books to my kids, so, I thought I’d give it a go. Despite the subject matter, three planes crashed during one year in 1950’s Elizabethtown New Jersey (based on real life events), it’s an enjoyable read. It isn’t complicated, it doesn’t require deep pondering, and has some interesting insights into life and social mores of the 1950’s which I enjoyed and was able to read quite quickly. I won’t say I loved it, but it was a pleasure to read.

I’m also just about finished my challenging book which seems to be taking forever: the 2001 Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, by Michael Chabon. I had heard of, though never read, anything by Chabon. When I was reading a collection of Nora Ephron’s essays that I picked up at Value Village, she waxed poetic about the power of fiction to escape one’s life citing Kavalier and Clay as powerful example of a quintessential New York adventure story. Not going to lie, it’s a tough, though thoroughly enjoyable read. Chabon blends historical facts and figures, Jewish mythology and folklore, with fiction to create the tale of two Jewish comic book creating cousins before, during and after, WWII. Overall, he plays thematically with the idea of escape: from tyranny and the confines of social and familial expectations ultimately leading to personal liberation. My favorite thing about the novel is the comic book references.

Next on deck for me is the book club read which this month is, How to Pronounce Knife, by Souvankham Thammavongsa. I’m just about to crack the spine and begin. What a great feeling!

Heather Paul has worked as an art teacher, a canoe trip leader, a yoga instructor, at a men’s prison and a women’s shelter. Her short fiction has appeared in numerous publications. She currently lives with her partner, children, and dogs in Ontario.

Photo courtesy of Andres Urena