Uncategorised

Finding the Form with Kasia Jaronczyk

On the Value of Things

Every time I fold my pre-teen children’s laundry, their graphic t-shirts, colorful socks, bright sweatshirts, and remember their cute onesies and hats with animal ears when they were babies, I’m amazed at how beautiful their clothes are and how many they have. I think back to my time as a child growing up in the 1980’s in the Polish People’s Republic, where I had to wear my dead grandfather’s socks because there were shortages. My brother and I had only a few pairs of identical underwear that was difficult to obtain, (looking for separate styles for different genders would be impossible), two pairs of shoes – sneakers to wear in warmer weather and boots for the snow, and very few clothes that seemed to grow with us. In my childhood photos I am always wearing the same outfits: when I am very little, the sleeves of my sweaters are rolled up over my chubby toddler arms, and several years later, when I’m school age, it is the same sweater but the sleeves are three-quarter length on my skinny pre-teen arms. In even later photos, my younger sister is wearing it.

When I see my children’s toys, markers, crayons, notebooks scattered among discarded clothes on the floor of their bedroom, I wonder about the value of things. How some things do not have an intrinsic value, and that their value lies in how we feel about them. I don’t want my children to lack anything; on the other hand, sometimes I feel like they don’t appreciate what they have. I remember how excited and astonished I was when I received a pencil with an eraser on top one day. I had no idea such things even existed! For back to school shopping my parents made a trip to downtown Warsaw to a big department store and stood in lines to buy a few Chinese-made fountain pens, wax crayons whose marks did not peel on paper. The box had an elephant on the lid that I remember to this day. If we were lucky they would find scented erasers with pictures printed on them and magnetic closure pencil boxes – iconic items which can be found on a lot of communist nostalgia websites today. Even certain kinds of foods were special. The waiting for the Christmas or Easter feast with ham, sausages, different kinds of fish, oranges, and other rare items, was what made the holidays special. We often received chocolate, salted peanuts and oranges as treasured gifts. The foods which my children could have any time but don’t particularly like or desire.

A lot of people in Poland are sentimental about their disadvantaged childhoods where a lot of necessities were special, even toilet paper. There are several famous black and white photos from that time of lucky shoppers proudly carrying a wreath of toilet paper rolls carried across their torsos like a beauty pageant winner’s sash. However, there is a danger in that kind of thinking, the nostalgia for our communist childhoods that excludes the negatives. I was lucky not to experience any serious lack of food or other provisions, my parents did everything they could so I never felt hungry or cold. Because I was a child during Communism, I did not experience censorship or physical abuse from the military police or any frustration with my job prospects for the future. I did not have to struggle to provide for my family. The memories of my childhood are peaceful and happy, and do not reflect the economic or political reality of those times. It is very easy to forget that.

But there were a lot of things I hopelessly desired as a child, among them were toys that came from the forbidden West. One of them was a Dutch Sindy Doll called Fleur – a European version of the Barbie doll coveted by all the little girls in Poland. I remember I had longed for Fleur, kept asking for it for several on my birthdays, and was very disappointed year after year. I don’t think my children had ever waited longer than a couple of months for any toy. They don’t know what it is like to want something so much. There is value in waiting, in expectation and imagining what that toy and playing with it would be like. It was a long time until my parents were able to purchase it from Pewex, a special store in Poland where you could by Western goods for American dollars or special cheques from the government bank.

There are lasting effects from that kind of life – I have a lot of unused art supplies because I feel they are too nice for me to waste on bad art; nice clothes hardly worn because I am saving them for a special occasion that never comes. I collect different kind of dolls. Perhaps too many. I often look at my children with a strange envy when they carelessly rip open packages of markers or crayons, and immediately use them, the way they carry them outside, or leave in different rooms of the house where they often forget them. When they wear their favourite clothes every day unconcerned about staining or ripping them.

When last year Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie came out and people started talking, yet again, about Barbie and all the bad cultural stereotypes it represents and how it negatively affects young girls’ self-esteem I decided to write about what it meant to me. How the Fleur doll, along with chewing gum, Lego, and jeans epitomised the West, freedom and bounty. This again comes down to the intrinsic value and meaning of this woman-shaped doll. It is just a piece of plastic, but at the same time, it represents an unrealistic and unhealthy beauty standard. However, would a child playing with it notice this if she hadn’t heard her mother complaining that she looks fat, if she hadn’t seen photoshopped images of women in the media. The doll’s value should lie in its play possibilities, not in what it represents according to adult biases. For me, the doll’s beautiful wardrobe made me imagine my future outside the grey communist life and its deficiencies, in which I could wear something different every day and own more than just two pairs of shoes. The bendable legs and arms were features that made it come alive. I would never dare to cut my doll’s hair or paint on her with markers. She was too precious. I had only one.

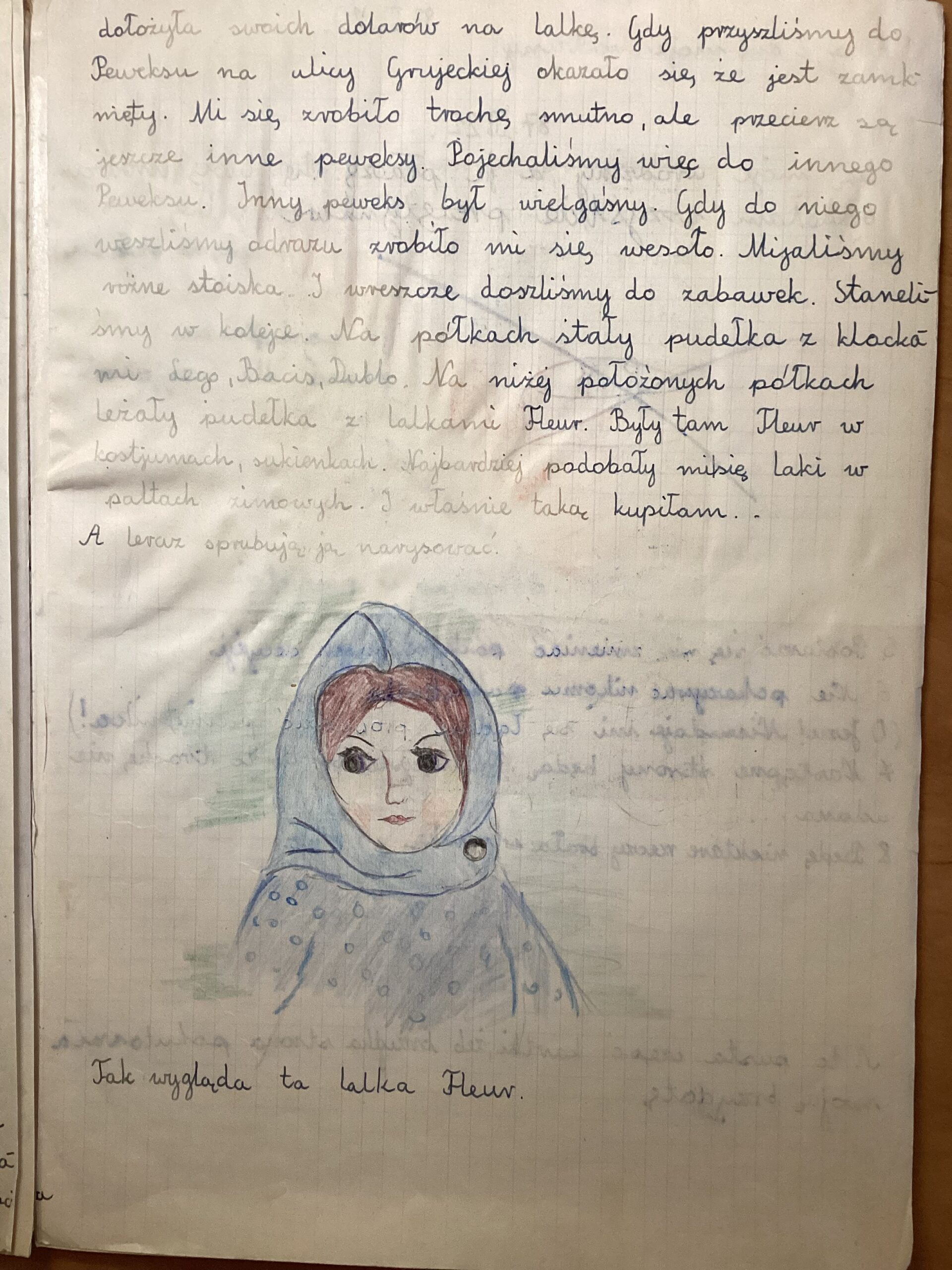

To write this essay I looked through my childhood diaries in which I had written about and drew a picture of the Fleur doll when I had finally received it. On the internet I found photos of the specific doll I had chosen. I researched the details of how Polish people had access to the forbidden American dollar – the black market, and what the Pewex stores that carried Western goods looked like.

My Communist Barbie essay flows naturally from the memories of my childhood to my present when I watch my children play. I describe the moments from my life in The Polish People’s Republic that are parallel or opposite to my children’s, so that I could compare and contrast them in the essay. I included what I thought were interesting details from my childhood in Poland beyond toys and games but which coloured my childhood and were for various reasons memorable. Just like I’m doing it here.

And finally, I looked for the child that is still very strongly present in myself and how I connect with her in my life.

Kasia Jaronczyk is a Polish-Canadian writer. Her novel Voices in the Air is upcoming from Palimpsest Press in winter 2025. Her debut short story collection Lemons was published in 2017 by Mansfield Press. She is a co-editor of the only anthology of Polish- Canadian short stories Polish(ed): Poland Rooted in Canadian Fiction (Guernica Editions, 2017). Her short fiction was short-listed for Bristol Prize 2016 and long-listed for CBC Short Story Prize 2010.

Photo by Maksym Harbar on Unsplash

A Spring’s Hope

The X Page: A Storytelling Workshop

A Spring's Hope

by Reem Elkady

I breathe in and breathe out as I close my eyes, the crush of the crowd washing over me. I can feel the familiar skin pricks, fists tense as my throat closes up and my breathing gets shallower and shallower. Yes, this is a crowd and yes, I should be running for the hills. Far away from any form of people congregating in a confined area.

But not tonight. I straighten my back, square my shoulders and pick up the pace, following my husband, my hand in his, deeper into the throng of bodies. We have to navigate closed-off and packed streets to get to the downtown square. A sense of calm washes over me as I glance at the majestic seated lions guarding the exit of the Nile Palace Bridge. Tonight, it seems like they are looking on with pride, telling us to be brave and go forth.

I look at Adam’s back. His little curly-haired head is turning from side to side, wide-eyed and silent, the yellow glaze of the street lights reflecting off his glasses. His five-year-old sense of wonder is endearing. Sitting on Shady’s shoulders, he must have an amazing view of the crowd, or does his autism make the sea of floating heads something intangible? He’s uncharacteristically engaged and present and it makes me grateful for small blessings. So I start counting; the cold, crisp air that fills my nostrils and carries the overwhelming smells of smog, roasting corn and the vague whiff of night jasmine far away. The short, sunny days and long February nights that make dealing with the sticky, sweaty bodies a welcome relief. The hazy orange light that engulfs a city that never sleeps makes me thankful for the glow that paints the packed streets with an air of celebration instead of foreboding. And if I’m counting blessings, the biggest one is that I don’t need to be on my usual extreme guard around all these men.

And they are mainly men. We pass the occasional woman here and there; a sister, a friend, or cousin—never alone—with an entourage of family or friends to protect her.

The streets of Cairo, as usual, are predominantly composed of the male of the Egyptian species. And, they are unfriendly streets towards women. I can’t remember a time when catcalling, harassment, and unwanted physical advances were a given for any woman that dared to walk Cairo streets, whether alone or not—it was something that they

drilled into all of us from a young age. Instead of criminalizing the boys and men for their behavior, teaching them to respect women, it is we who carry the burden of always being on our guard, and wary of the harm that could befall us. But like all the other blessings and surprises of this night, I don’t have to worry about any of it for now. Tonight, I want to be part of this crowd and this crowd wants me to be part of it; woman, immigrant, atypical Egyptian that I am. And for the first time in what seems like forever I feel like I am one with a crowd.

I look to my right to check on my best friend, Maha, and her husband. Her six year old son is hopping excitedly on his father, Amr’s shoulders as we weave through the crowd

around the United Arab Nations Building. Hamza has a huge smile on his face, wonder in his eyes and a continuous babble that goes on and on about the thrill and awe of being there. I am grateful for his joy and envious for the fact that I never experienced that same sense of oneness or belonging in this country—or any country.

We reach the makeshift checkpoints set up by volunteer protesters. We stand patiently waiting as they ask the questions: Why are you here? Are you carrying any concealed weapons? Can we please look through your bag? Then they notice our two young boys sitting on their fathers’ shoulders, and they wave us through with a smile.

As we emerge from the shadow of the stoic, post-modern government complex, Tahrir Square in all its glory, hits us. People fill every corner of the street, gardens, sidewalks

and pavements as far as our eyes could see. It’s the zenith of night, but nothing is dark. Light from street lamps and building spotlights along with the haze of a city of 80 million

envelops us in an orange and warm embrace. Ahead is the statue of the stony horse-backed general, some revolutionary soldier from a forgotten time, silently witnessing something familiar but oh-so-foreign to him.

From the edge of the crowd, we hear laughter, loud conversations, and faint cheers coming from a makeshift stage set at the end of Tahir Road. A small group of protestors takes turns talking to the people. I’m too far away to hear the words but the most important chant carries over the breeze; ‘Bread, Freedom and Social Justice!’

Suddenly, people start shifting and bending. As I look all around me, everyone is bent over, focused on their feet as they slip off one shoe. I look back at the stage where the group stands, each of the speakers has one shoe raised high in the air. They start chanting ‘Erhal’ and the crowd is chanting back ‘Erhal’. One word— Leave—repeated

over and over. Tens of thousands gathered with one goal in mind: bringing about a peaceful and just change!

I have goosebumps again, not because I’m trapped in a crowd, but because I am lucky to be alive at this moment in time, to be present. To be physically here to witness a momentous point in history when the will of the people prevails and all of the wrongs are made right.

I set my backpack down and check on Adam. He is still awake, but just barely. Resolved to absorb it all, he crosses his hands on top of Shady’s head and rests his cheek on them. I look over at Hamza on his father’s shoulders. Unfazed by the lights, sounds and chanting, he’s fast asleep. Amr’s shoulders ache and my husband offers to carry Hamza for a while. As they gently bring Hamza down off his father’s shoulders, the men around us notice the sleeping child in their arms and the equally drowsy boy in mine and a

whisper starts encircling us. The crowd parts, revealing the pavement, and jackets, scarves and blankets start flowing in as people offer anything they have that is soft. Two men insist on taking the weight of the children from us. They were complete strangers, but the camaraderie and shared goals connected us in that moment, and they are

strangers no more. They sat down by the borrowed clothing on the pavement, and we passed our sleeping children to them as they gently laid them down on the makeshift beds, heads on their laps. The rest of the group circle them, protecting Hamza and Adam as they sleep.

Me, Shady, Maha and Amr stand there for a few moments, overcome with a wash of emotion, love, and purpose before we collect ourselves and start chanting ‘Leave’. And for tonight, we are whole. We are all Egyptian, and we all belong.

Read more

After 12

The X Page: A Storytelling Workshop

After 12

by Sidra Khan

It’s 12:45 a.m. The doorbell would ring any moment now. I’m in the kitchen, collecting a plate and two small bowls. I start looking for the fancy tray. This tray could easily call itself royalty, with its unconventional shape, dark color, and dull gold handles. My mom keeps this tray for the guests. I’m going to be the guest today. Maybe I’ll make tea.

I turn around to see my brother, Abdullah. He did not ring the doorbell, as expected. He is already in the kitchen doorway with my paratha rolls. I take them from him, trying to avoid eye contact. I can feel his eyes and an innocent smile plastered on his face. I turn my back to him and become a tall wall between him and my food. He is 6’2. With the weight of his hungry eyes on my back, I forget about the tea.

Typically, when my brother has joined my midnight food excursions, I’ve either lost my appetite or given into my brother’s interrogations, “Kaisa hai roll, garam hai? Tmhare

liye taaza banwa kar laya hun.” He never brings anything for himself. Instead, he stares at my food until I feel bad enough to give him half. Then he pretends to be surprised! “Arey tmne mere liye bhe bacha dia!” as he still stares at my plate.

I want this time for things to be different. I’m starving.

I salivate just thinking about the tikka-flavoured, crispy pieces of chicken, tightly wrapped in a hot crispy paratha. My biggest problem is deciding which chutney I will dip my roll in. There’s Imli chutney, dark brown in color with a blast of sweet, and tangy flavor. The other is hari chutney. It’s green and made of mint, lemon, and cumin seeds. I imagine dipping the roll in both and seeing the blast of flavours that it would bring.

My hands fumble as I put together the food on the tray and worry about finding a quiet spot. My brother follows me like a death angel.

He sits on the floor across from where I am seated. I am a few bites in when he starts to tell a story. Only he knew what he was talking about. I am completely disengaged,

hypnotized by the paratha roll in my hand.

Tonight is different. It has been decided by the divine! And my hunger pangs.

I look up and pretend to be interested in his story, but I don’t smile. I keep chewing the hot, yummy paratha roll as I stare down my brother. I see hope in his eyes. A smile

starts to spread across his face as he struggles to pretend he doesn’t care about my food.

I look at the last big morsel of paratha roll in my hand. I hold it so he can take a good look at it. I open the roll to fix the onion and chicken then I slowly refold it. I take the morsel and dip it in the last remnants of the chutneys. I have to scoop up all the remaining chutney from both the bowls and also make sure it doesn’t drip off.

While I try to balance the perfect bite, I feel my brother edging closer to me. He is also speaking louder than before. “Yeah and then the sister gave the food to her younger hungry brother because he didn’t have his own.”

I meet his gaze. “Well, the brother should’ve gotten his own food.” And stuff the last bit of roll into my mouth. I smack my lips as loudly as I can. I savour the last of my paratha

roll and the disappointment on my brother’s face.

Read more

A-N-A

The X Page: A Storytelling Workshop

A-N-A

by Georgina Fernandes de Barros

I stand side-by-side with my grandmother as she kneads the sticky yellow dough. Avó—it means grandmother—throws her entire skinny body into the dough, and the table is covered in white from her exertions.

I am four years old, and am on a step stool so that my hands reach the floured surface of the kneading table—the “mesa masseira”. The mesa is cornflower blue—my

grandmother’s favourite colour—and when I picture her, she is wearing a cornflower blue apron, and a patterned scarf to hide her hair from any sudden strangers. My grandmother is tiny, bird-like, and her elbows and knees are wider than their limbs. But she has big, deep-set gray eyes that sparkle with humour.

She makes an excellent “pão de milho”, a regional delicacy. It is an almost spongy bread with a thick brown crust, made of corn flour and rye, and baked in a clay oven. My grandmother is a terrible cook, and her bread is the only exception.

I had been begging my mom to go to school for awhile now, but she said I was too little. As consolation, we would play school at home. While she would make dinner—or generally did other mom things—I would be sat at the kitchen table with a notebook and pencil. She taught me the letters first; pages of “a’s” and then “b’s”. I stumbled through “f”, the hardest letter in Portuguese cursive, and then all the way to “z”.

That accomplished, my mom has taught me how to combine these letters into the names of everyone in my family. Writing everyone’s name down on paper makes me

feel like a wizard, like I have access to their power by having access to their names.

Empowered now by this knowledge, I dip my finger into the flour on the table and write in big letters: A-N-A. Ana. My avó’s first name.

I wait for her to notice, feeling proud that I know her name, and mischievous for daring to show her I do. But my grandmother continues to knead the dough exuberantly and doesn’t notice.

This simply will not do. “Look, avó.” I point to her name.

She looks over briefly, and does not react. “Oh? Did you draw a little picture, child?”

I shake my head. I have forgotten—my grandmother never learned how to read or write; she is illiterate. “No, avó, it’s your name. A-N-A. Ana.”

Here my grandmother stops. Her arms are full of flour, and her eyes are full of wonder.

“What?” she says. “It is? You can write?” Then she raises her voice: “Velho! Anda cá! Come see what your granddaughter did!”

My grandfather comes into the kitchen slowly, to remind my grandmother that he chooses to come. My grandfather is tall, with snowy hair, and watery cornflower-blue eyes. A hand-rolled cigarette sticks out from between his lips.

My grandmother points to the mesa excitedly. “Look!” she says. “Can you read that?”

My grandfather moves over and squints down at the letters in the flour. He can read a little, but he is out of practice, so it takes him a moment. When he recognizes the word, he turns to me in surprise.

“You wrote this, girl? You can write?” he says.

I almost fall off the stool with excitement as I say, “I can write your name too!”

I trace six more letters on the table. M-A-N-U-E-L. Manuel.

“That’s my name!” my grandfather tells my grandmother. He chuckles then, a low smoker’s rumble from his chest like he is mixing gravel somewhere in his solar plexus.

My grandmother’s voice sounds awed as she speaks, “Isn’t that something? Here I am, an old woman who can’t even write her own name. And you are four years old, and already ahead of me.”

I stare up at both of them, at their shining faces, and I am overjoyed to have made them so proud.

Dream House

The X Page: A Storytelling Workshop

Dream House

by Andruly Alpala

When I was a girl, I lived in my dream house on a mountainside in Colombia. My father helped to build the house before I was born. He died when I was nine months old. The house belonged to my grandma.

Living in the mountains meant not having electricity or other fancy stuff. We woke up early, and went to bed early too.

This morning, I’m half-awake. I smell firewood and fresh coffee. I see the sun shining through the cracks in the door. As always, my aunt and my mom are already up and ready for the day.

And today is very important—because I’m starting my first job! With my aunt! I’m going to work at her daycare. This makes me happy because I plan to buy blue jeans and a yellow bathing suit with my first payment.

But my first day isn’t starting too well—I hear my aunt say that she will leave in ten minutes.

I run to the bathroom to take my extra-cold morning shower. It’s difficult to jump in, but the fresh cold water gives me energy. After my cup of coffee with two cheese

empanadas made by my mother, I say loudly, “I’m ready! Let’s go!”

My aunt is waiting for me.

I cannot leave without the bag my aunt made for me, because it holds all my stuff. In my mind, I’m preparing for my job as a teacher, eager to finish everything on time so I can play with the kids. But my aunt has other plans. I’m only fourteen, and she wants me to help with cooking. On my first day, she tasks me with chopping onions; I don’t like chopping onions because they make me cry. But I want to show my aunt that I can do it, so I tell her, “Don’t worry, I can handle it.” She just laughs and says, “We’ll see.”

We start to walk down the mountain to the road—this takes around 45 minutes. But when we’re together, we walk slower. It’s our special time to talk about everything. My aunt tells jokes and gives me advice. She warns me not to have a boyfriend because I’m still young. She says I should focus on studying. She shares her own not-so-great experiences in love to emphasize her point. Yet, despite her warnings, she eagerly shares all the exciting moments she’s lived through. I wish I could record all these moments and conversations with her.

Today, while we’re walking, I see something green move suddenly. It’s a snake! I scream because I’m scared of animals, even though I live in the mountains. I run away as fast as I can. I hear my aunt saying, “It’s okay, the snake is not following you!” But I can’t stop running. I’ve never gone down the mountain so quickly. Finally, I arrive at the road.

Now, I’m waiting for my aunt.

When she arrives, she laughs, and I laugh. On this first day, I will not be late for work.

Read more

Flammable

The X Page: A Storytelling Workshop

Flammable

by Hala Alzain

Springtime in Kuwait is the perfect time for picnics. Actually, it’s the only time for picnics. For those who aren’t familiar with it, Kuwait is a small, peaceful country in the Middle East, where for most of the year it is very hot.

One spring day when I was eleven years old, my family joined a few other families for a day at the beach. Being a typical Syrian family, we packed a lot of food. Food determines whether a picnic is a success or not. We kids had a different way of judging picnics. For us, the more we could play, the more awesome the picnic.

On this day, we raced each other up and down the hills and laughed when someone fell and rolled all the way to the bottom. Covered in bruises, we kicked off our shoes and ran to the sandy beach. There we collected shells, looking for the most beautiful and unique ones.

As I was digging, I found a spray can. I picked it up and was about to toss it aside when I spotted a symbol on it, a little red flame inside a triangle and underneath it, the word: “Flammable.”

I had an idea.

Back then I was a curious child. Some might have called me a naughty child. But I think I liked to experiment. I wanted to try things, usually dangerous things, to see what would happen.

My friends gathered around and asked what I was thinking. As soon as I was finished sharing my plans, they scattered along the beach, gathering any materials that could be used to build a fire.

It was a perfect example of “one person’s trash is another person’s treasure.”

Not long after, we stood in a circle and watched our friend Ahmad light a fire. I stepped forward, raised my arm, and threw the can into the flames. We held our breaths as we watched, waiting for sparks or maybe an explosion. We were so excited we didn’t notice our parents running over at the sight of smoke.

My dad was at the front of the group of parents. By then I had a history of doing crazy things.

Suddenly, I felt myself pulled up and away from the fire. At first, I thought it was the force of the explosion that lifted me. But right away I realized it was my dad holding me. Other adult hands threw sand over the fire and put it out before the can exploded.

No one was hurt but I was in big trouble. Not only with my dad. I spent the rest of the picnic trying to convince the other parents I was just a kid who wants to explore the world.

Read more

Masala Dabba

The X Page: A Storytelling Workshop

Masala Dabba

by Sanjana Srikant

Jeera, kadugu, dried red chilli, urad dal, and of course, turmeric. The five spices in my mum’s masala dabba.

I remember sitting on the marble kitchen counter at the house I grew up in, in Chennai. I was three, maybe four years old. I sat transfixed as Amma boiled water in a steel saucepan for the first round of chai of the day. It was our quiet, loving, daily ritual. I watched the graphite-like leaves swell and foam when they hit the boiling water and breathed in their earthy aroma, sweet and malty with a hint of bitterness. It was magic.

But soon enough, I grew bored. Amma knew just what to do to keep me from pestering her. She handed me the masala dabba. A wide, shallow, cylindrical steel box with a translucent lid containing five congruent small tumblers, each with its own spice and a tiny measuring spoon.

It contained everything I took for granted and became everything I would yearn for as I put years and miles between that child on the counter and the woman I am now.

Turmeric is vibrancy and life.

2014 Chestnut residence, the University of Toronto.

Amma and Cheeka (that’s what I call my dad; he won’t answer to anything else) just moved me into my dorm room. I have a spectacular view of the Canada Life building with its imposing façade on tree-lined, regal University Avenue. Everything sparkled under the noon-day September sun.

I’m going to meet people from everywhere! I’m going to learn SO much! Omg I don’t have a curfew!

Kadugu is small, feisty, spluttery, and explosive.

2018 Queen’s Park Subway Station

I stood at the intersection of University Avenue and College Street gazing up at a row of country flags. I had hurried over those pavements every day for four years. Today, I was stopped in my tracks by a flood of memories of moments, people, and places, spinning around me.

Oh the places you’ll go, darling girl. Plenty of life left.

2021 to 2022

Chennai, Beach Road

Amma was sick, so I left home (did I just refer to Canada as “home”?!) and went back—well, home. I rediscovered a child-woman. Quiet, resilient, a receiver of stories. I found my people, and among them, old, buried family treasure, wounds that needed tending, and I gave care.

Hello, there. It’s been a while, hasn’t it? I’ve missed you.

I’ve missed you too, my love.

Dried red chilli is wisdom, lending comforting warmth, and unapologetic heat.

Now, the University of Waterloo

I began to learn how to treat myself the way I would a dear friend—slowly but surely, speaking encouragingly, patiently, and respectfully. I sat beside discomfort without fear and distrust.

In the center of the masala dabba is an empty spot, where a perfectly circular vial would fit, only Amma didn’t have one in there. I think about that now. How it holds space. In the center of everything is an empty space. Am I that empty space?

Read more

Don Juan Alba’s Daughter

The X Page: A Storytelling Workshop

Don Juan Alba's Daughter

by Raquel Streppel

The air in the kitchen smelled of fried onions, fresh garlic, and oregano. My Dad was slowly stirring his unique tomato sauce with his mom’s old walnut concave spoon. My grandma used the same spoon to make jam in the past, strawberry jam, the staple fruit of my town, Coronda.

My Dad’s sauce was simply unmatchable. Was it the way he patiently stirred it? He had his cooking secrets. I wondered whether that spoon, his mother’s spoon, was his “wand” to turn those simple ingredients into something magical with the power to transmit his love for his family and his passion for life.

All together, my family was making gnocchi. My Mom, Dad, three siblings, and me—I was about ten years old. Daniela, the kindest sister you could ever have was almost two years older than me. Carlitos, the eldest of the siblings, handsome, athletic was somewhat of a rebel. I remember my parents arguing about Carlito’s ways. Inesita, who was five years younger than me, was also there, but completely unaware of the metamorphosis that was going on in the kitchen. I was concerned not only with making the gnocchi but also making sure that the table was perfectly set. Everything had to be neat, clean, and in the right place, paying close attention to all the details. Now, I understand that was a characteristic of my zodiac sign…a Virgo.

Gnocchi were mandatory in my family home every 29th of the month, no matter the season. This was an Italian tradition my parents grew up with and passed on to us all.

Why gnocchi on the 29th? Well, gnocchi was a go-to recipe for the Italians who had immigrated to Argentina. Italians had to make their meager salary last till the end of the month, and making gnocchi was an affordable yet nutritious meal.

The coming of Italians to Argentina was due to two main reasons. First, the Argentine government fostered European immigration during the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Argentina was a land of promise away from the hunger and war.

Even though Italians were poor, their minds and souls were full of recipes, music, and dance. My Dad’s grandfather came from Angera, a town in the Italian Lombardia, next to Maggiore Lake at the end of the 19th century.

I remember helping my mom make this potato, egg, and flour recipe as if it was yesterday. My hands and fingers were sticky, and my clothes were covered with white flour. My mom would carefully roll the dough into logs with her palms, then she would cut pieces about three centimetres long, each as fast as she could. After that, my mom and I placed ridges on them using a fork. Two small rolls for each gnocchi. I tried hard to make them look like my mom’s, but my gnocchi were nothing compared to her perfectly sculptured pieces.

I enjoyed counting them all up and making a guessing game out of it.

“Guess how many gnocchi we’ve made?” I asked my family. My dad always was the best guesser. “198”, he said. Exactly what I had counted! How did he know?

We all had to place a bill under our plates; each bill came from our dad’s brown leather wallet, of course. He made sure that all of us had something under our plates. The idea

was to save the money till the end of each month, or we could just spend it right after our lunch on ice-cream. There was always an ice-cream truck or scooter going by our

neighbourhood, riding the old sandy streets, breaking into the “summer siesta” with its loud piercing horn, shouting “helado”—”ice-cream” in English. As soon as we heard the ice-cream man nearby, we grabbed the money under the plates and rushed outside barefooted, running after the truck, waving our bills in the air. We would get ice-cream bars for the whole family—no ice-cream cones at that time—and only three flavours to choose from: “Dulce de Leche”, a sort of caramel sauce; “Granizado”, something like crème with chocolate chips and “Frutilla”, strawberry, the best one.

But lunch was not over till our dad performed. Yes! My dad had the voice of a tenor. We would wait for him to start tapping on the table or on the fridge before his “12 Cascabeles Lleva mi Caballo” song, “My Horse carries 12 bells”. My dad went from tapping on the table with his knuckles to demonstrate the way the horse trotted to clapping his palms to pretend he was a Spanish flamenco singer. This last movement was a prelude to “La Hija de Don Juan Alba’s song” or “Don Juan Alba’s Daughter.” My favourite one. Apparently, Don Juan Alba’s daughter wanted to become a nun instead of marrying her fiancée, despite having bought a long white dress.

But I was especially drawn to this song because I could see how happy and confident my dad was when he sang it. He was born to be a singer, but we were his only audience.

And when I think of “La Hija de Don Juan Alba” now, I cannot help admiring “Her” determination and courage in following her own dreams and convictions…despite the challenges. A message carried from past to present, from father to daughter.

I miss him very much.

Read more

When No One Is Looking

The X Page: A Storytelling Workshop

When No One Is Looking

by Eunice Owusu-Amoah

I…may have done something…dumb.

I am, maybe, nine, ten. I stand in the corner of the bedroom I share with my three older sisters. The fire…is small, so I am only slightly alarmed. I lit the piece of paper and dropped it on the ground. I am no longer a lighter of fires on little matchsticks quickly put out in fear. Now I am a lighter of pieces of paper…just to see.

The small fire grows. In the sudden perceived darkness of my surroundings, lit up by the scarlet at my feet, I am abruptly aware of my stupidity.

I pick up a little plastic cup of water from the bedroom table and dump it on the fire. But the fire grows bigger, and I know I am doomed. Why has my curiosity led to this? Then, the flames calm and disappear. Never to be mentioned. But they say something about the word, ‘never’.

Many years later, I will mention this hazy, ‘created a fire in our bedroom’ memory to the sister preceding me. She will say, “Oh yeah, back then we used to light matchsticks and pieces of paper.” “We?” I will exclaim, amazed by how she’d named my exact tools and materials before I mentioned them! She will clarify that she had simply been doing it before me and had learnt it from the sisters before her. It is wonderful to know they shared my childlike stupidity.

When no one is looking, I do what I want.

I am, maybe, eleven, twelve. In my classroom, I sit in the sun’s white rays. It is break time and only I remain, a storybook beneath my desk. The best time to read books is in dramatic sunlight.

Plus, I am not reading this story over anyone’s shoulder, nor rushing to finish so they can flip the page. I take a slow-motion bite of my overly sweet Super2 biscuit and a relaxed, swirling, sip of my Pineapple Kalyppo juice box. The laughter, chatter and play outside…do not exist.

When the English teacher enters and comments that I must be a fast reader; I’d made much progress from yesterday, I laugh and answer that I am not a fast reader. I respond that, last night, I read until five a.m. before waking for school at six a.m. This is true, but I do not tell her that throughout her class and many others, the book also remains open beneath my desk.

Others do this too, but my book has not been confiscated yet. Probably because I hide mine better.

Yes, it is not all danger and mayhem. I am like every other child: curious.

I am, maybe, eight, nine, and I’m in my parents’ usually locked bedroom. I sit on the plush blue toilet seat cover of their bathroom. They are not home yet. As I rot on the seat with my mum’s Samsung Galaxy tablet, the device and I sink into the dim blue darkness of night. You know how it is: when you sit on your business long enough, you don’t smell anything anymore.

I watch Mr. Bean dance his animated little dance. I watch movies with characters and storylines strangely similar to The Lion King.

When I hear the bedroom door open, I flush the toilet, even though I flushed long ago. I stroll out, give a quick “hi”, and slip the tablet back on my mum’s side table.

They say, “She’s a quiet one,” but they say other things about the quiet ones: Words like dangerous and troublemaker.

I am, maybe, ten, eleven. I stand before my mother, the yellow living-room couch pulled back, and the half-eaten fufu hidden behind it revealed for all to see. Against the creamy wall, the fufu is a sickly pale colour. Luckily there is no smell. When my mother moulded the mashed plantain and cassava into a ball, I said, quite clearly, I thought, “It’s too big.”

She chose to ignore me.

This is what happens when you’re a child who ‘doesn’t eat’. They say, “Eii, won’t you eat? Don’t you eat? So, you won’t eat? Ahh, you don’t eat ehh?” So, when my family left me alone at the dining table with my unfinished food, I looked to the living room a few steps to my right…

Now that I have been caught, I feel two things. First, ashamed; I lacked the foresight to see beyond, ‘where can I hide it?’ Second, proud; even I had forgotten I put the fufu there! Who else but me would have thought of such a great hiding spot? Some years later, not far from this great hiding spot the carcass of a mouse will be found. Through no fault of mine, of course, because I will choose a new hiding place after getting caught; the uncared-for garden at the back of the house.

This younger Eunice is curious. Curious about the spaces she can create just for herself, the stories she can discover, the problems she can cause and the problems she can solve. I wonder…is she so different now?

Read more