Deepa Rajagopalan’s Writing Space

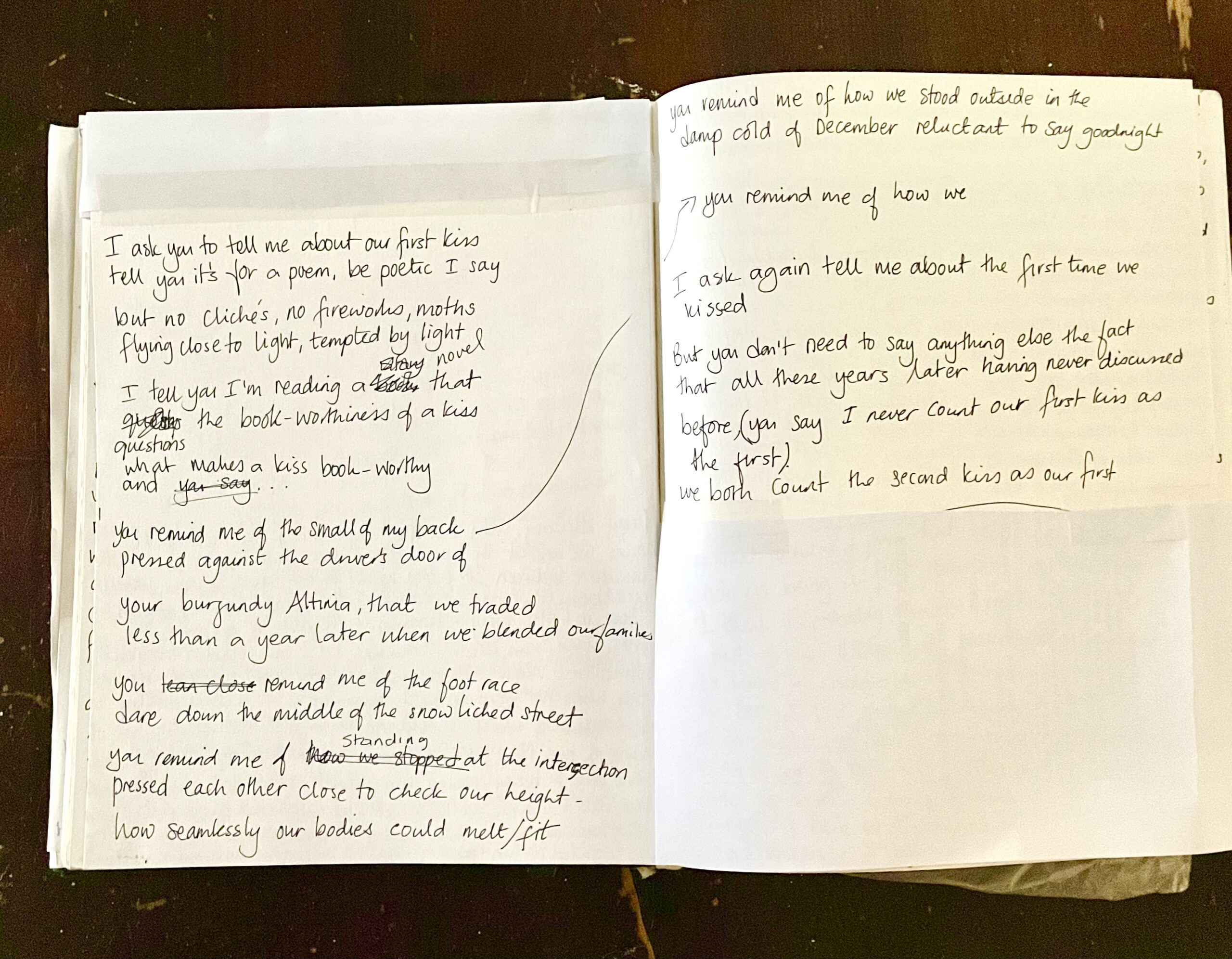

Orhan Pamuk said in an interview with the Paris Review that he thought that the place where he sleeps, should be different from the place where he writes. That the domestic rituals and details kill his imagination, and so he always had a little place outside the house. I sometimes imagine having a space like that, away from the dishes and the refrigerator and the laundry. But for now, I write in cafes, on trains, in hotel rooms during holidays, on long walks, on a chair beside the fireplace, and in my study.

There’s a café near my place which I like because it is filled with people who, like me, sit there for hours doing things no one asked them to do: writing, drawing, building businesses from scratch. The café is loud and bright and has bad Wi-Fi, all of which is good for writing.

A lot of the untangling in my writing happens during long walks. When I am stuck in a story, an eight-kilometre walk usually fixes it. It helps me think about the idea without holding it too tightly. Sometimes, a friend or two would call me during the walk and I’d tell them that I’d call them back because I was thinking. There’s a trail behind my house that is flat and boring and long, all of which is good for thinking.

“The café is loud and bright and has bad Wi-Fi, all of which is good for writing.”

My favourite place in my house is a corner beside the fireplace on an orange chair. I usually sit there first thing in the morning, before dawn when the house is so quiet that I can hear my dog breathing, and I read or write or think.

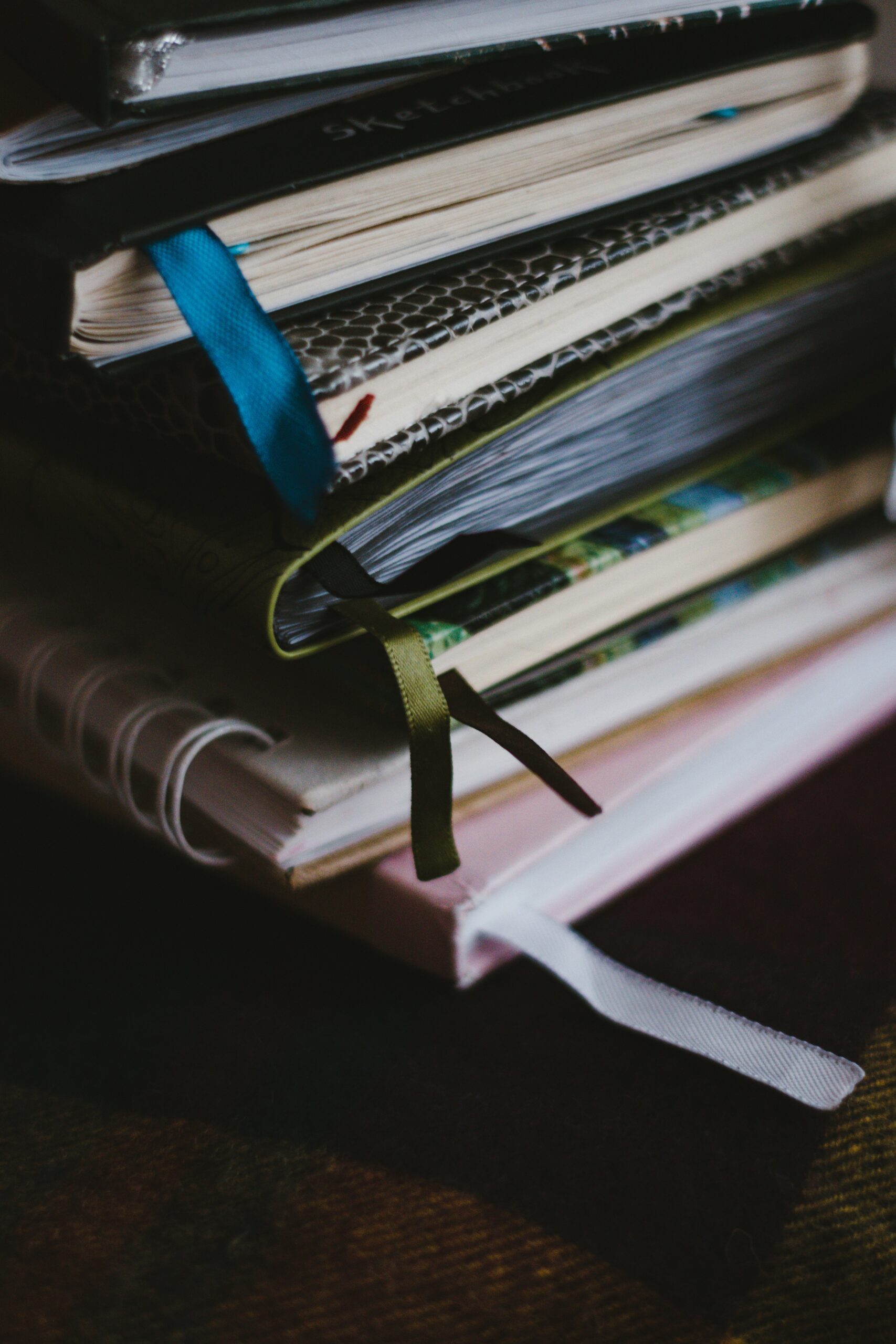

I mostly write in my study, at my desk on an uncomfortable but pretty chair or on a comfortable but ugly lounge chair sandwiched between a window and my bookshelf. My books are organized in no particular order, but I always have a stack of emergency books on a floating shelf beside my desk at arms length. These are books that keep me going when I feel I don’t know how to write. I also have a small stack of magazines ad anthologies that I’ve been published in and little treasures from my daughter and my friends on the shelf. There are pictures on the wall, artwork from friends and strangers, and a few photographs I’ve taken.

A lot of writing is staring, so I have a few low maintenance, good looking plants scattered through the study: a monstera, couple of pothos, an anthurium. Sometimes, when I’m supposed to be writing, I stare at the plants, at the new leaves unfurling and think about their beauty, and how there’s so much beauty in this broken world, and how I simply want to tell the truth about this beauty in my writing.

Deepa Rajagopalan’s debut short story collection will be published in 2024 by the House of Anansi Press. Deepa has an MFA in creative writing from the University of Guelph. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram @deerajagopalan. Visit her website: deeparajagopalan.com.