Finding the Form with Colette Maitland

It is in the doing, i.e. process, that I discover a story’s form. For me, form almost always springs from character development. The more time I invest getting to know my character or characters, the clearer the path forward.

Case in point: Miss Touchy Feely (MTF), who appeared in a previous story, Overtime, where the main character of that piece, Axel Connor, referred to her as MTF. (He didn’t know her name either.) Currently, I’m working on a linked story collection, so it was only a matter of time before I’d write a piece from MTF’s point of view. I began by taking stock of what had been revealed about her in Overtime. She was a police constable in small town Kanawasaguay. She didn’t grow up locally. She and her work partner, Constable Saunders, had been called to an apartment complex in the evening to speak with Axel’s mother, Mable, regarding her suicidal thoughts. Axel described MTF as having a mole above her upper lip. MTF assessed and provided comfort to Mable while Saunders spoke to Axel. I also knew the ‘now’ of MTF’s story would occur during the same day as the ‘now’ of Axel’s story. I needed to understand more about MTF before I could begin to write: an actual name for a start, but also more about her job, colleagues, private life and relationships.

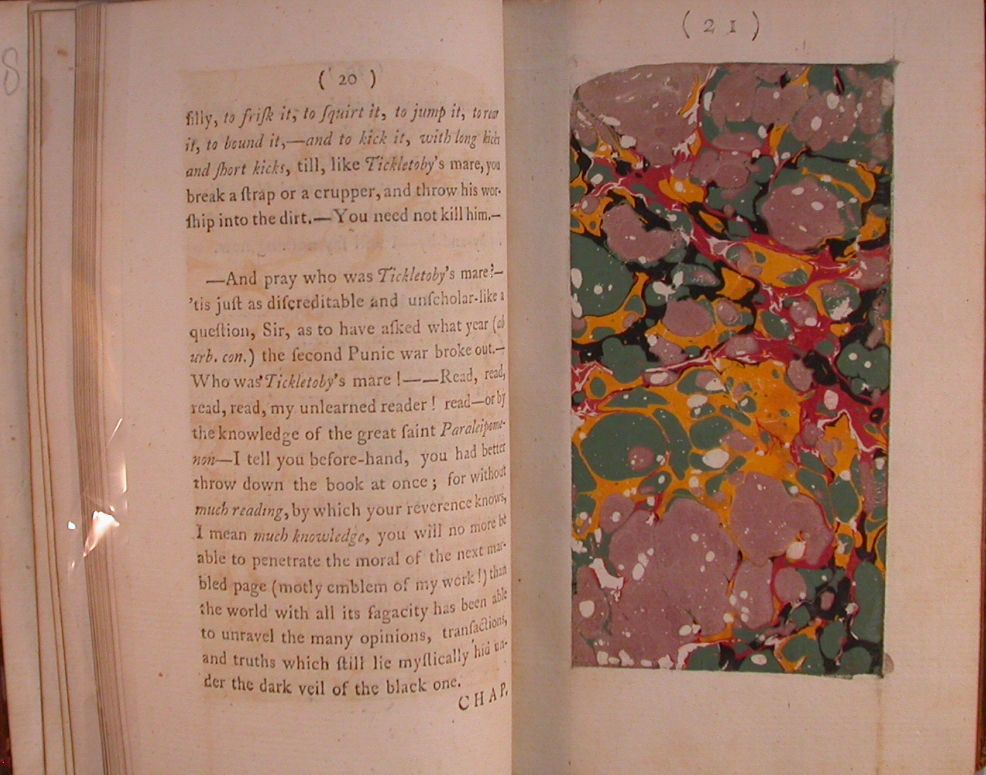

I began by researching policing, reading Gender and Community Policing: Walking the Talk, by Susan L. Miller. I took notes. I looked up information on-line about how one becomes a police constable in Ontario. I scrawled questions in my notebook – “At what point in the day do we take up with MTF?” “We know she’s not ‘from town’ – so where does she come from?” “How does she get on with her family – parents? Sibs?” “Could she be called to a local business to deal with some sort of situation?” I drew up a list of questions for two recently retired local police constables who’d agreed to speak to me. I took more notes, made a list of words related to policing: suspicion, community, rapid response, briefings, shifts, crimes, delinquency, etc. What if MTF was called out to investigate a minor crime at the beginning of her shift? A mink stole I’d once seen out front of a local business in my town came to mind. From my notebook: “there’s a junk shop on main street … outside the door they’ve set up a mannequin, headless…one of those sewing mannequins? – check proper name – displaying a fur stole – a ratty stole – hard to know what kind of fur … and the teen … has squirted a bottle of ketchup all over it in protest … the store owner … will know who the kid is…” Now there were three characters – MTF (still nameless), the kid, and the owner of the junk shop, but the ketchup bottle had quickly morphed into an aerosol can of red paint. I’d yet to scratch the surface of MTF’s private life.

Everything was fluid, I hadn’t written a word of the story. The characters needed development/depth. I scribbled more notes, questions, and came up with a name for MTF (Cathee), the shopkeeper (Rona Blunt). I identified the teenaged girl. So many puzzle pieces in my notebook, in my mind. Still, others were missing. Who were Cathee’s people? What happened in her past, what’s happening now in her private life? What if her parents divorced when Cathee was a teenager? Why? A great aunt appears. What if Cathee’s great aunt, now living in a retirement home, was instrumental in some way I’m not yet privy to during that period of domestic upheaval? How might all these factors impact or affect Cathee’s behaviour on this particular day?

What I know as I sit down to begin the first draft is that MTF, first name Cathee, last name undecided, will drive the narrative. I’m starting to see a shape. Cathee will appear at the junk shop, now called Vintage Chic. She’ll question the owner, Rona Blunt. At some point Cathee will have to deal with the kid. This story will wrap up before Cathee appears at Mable Connor’s apartment complex.

Everything’s still fluid, but I feel ready to let the characters play. Something Anne Lamott wrote comes to mind: “Just don’t pretend you know more about your characters than they do, because you don’t. Stay open to them. It’s teatime and all the dolls are at the table. Listen. It’s that simple.” (Bird By Bird)

Or that hard, depending on the day.

Colette Maitland has published two books: Keeping the Peace and Riel Street. Her short story “Downsizing,” was published in Best Canadian Stories 2021 and received the Metcalf/Rooke Award for best short story in that anthology.

Photo by Denise Jans on Unsplash