My Father, Fortunetellers and Me was released in October 2019. This is your second book with the West Coast indie press, Mother Tongue. What’s changed now that the book is circulating freely in the world? What are you learning from its reception, its audience—who loves this book, and why?

True story: My dad loves it, but he hasn’t read the book. Five fishy stars from him. He believes I’ve spun a golden memoir out of straw history because a few people have approached him and mentioned they loved the book. To clarify, these are neighbourhood folks he’s pressed into owning the book, and one fellow he loaned it to—he gave away several copies of the memoir and kept asking for a replacement. I teased him about being a terrible salesman and he came back with, “What difference is twenty bucks going to make in your life?” Safe to say my ego is not in danger of ballooning any time soon.

Readers who reached out have been diverse, and I’ve been heartened by their generous responses.

Let’s talk about patterns. Certain issues haunt nonfiction writers: how to depict people in ways that are truthful, authentic, but not hurtful; how not to exact revenge; how to avoid diminishing or punishing your characters. It’s the dilemma at the heart of making art from trauma. Your story digs deep into the family vault, exposing generations of harm, including a mother who is ill and suffering, someone who’s caused unending heartache for herself and others. How did you balance the enormous pressures that come with exposing family trauma with the tell-all expectations that come with writing memoir?

Let’s talk about patterns. Certain issues haunt nonfiction writers: how to depict people in ways that are truthful, authentic, but not hurtful; how not to exact revenge; how to avoid diminishing or punishing your characters. It’s the dilemma at the heart of making art from trauma. Your story digs deep into the family vault, exposing generations of harm, including a mother who is ill and suffering, someone who’s caused unending heartache for herself and others. How did you balance the enormous pressures that come with exposing family trauma with the tell-all expectations that come with writing memoir?

Ethics is a fraught issue that wakes essay writers and memoirists in the middle of the night. I wondered for ages about whether I had the right to tell my own tale because it would be impossible to write without including abuse, battles, and unfavourable portraits of people I care deeply about. The stories I chose to reveal were selected and distilled, organized and edited with an aim to give as authentic a report as I could about growing up with an ill, abusive mother and a depressed, passive father. The added layers of confusing cultural beliefs, complicated language barriers, inherited trauma, superstitions, and dealing with a broken medical system were demanding and worrisome. I was antsy about getting details wrong or about delving too deeply into the despair the situation could produce.

I kept a quote, “There are three sides to every story: yours, mine and the truth,” above my desk, and some mornings I lit a candle and recited an incantation asking my ancestors to assist me. I spoke in Molisan, repeating my intention to be a truth-teller, and to walk the path without causing further harm. Like everything in life, this is much easier said than done. There’s a code of secrecy woven into family chronicles, but silence begets trouble. Toxic patterns are allowed to flourish and continue unabated unless we’re willing to name the damage done and wrestle with the accompanying shame.

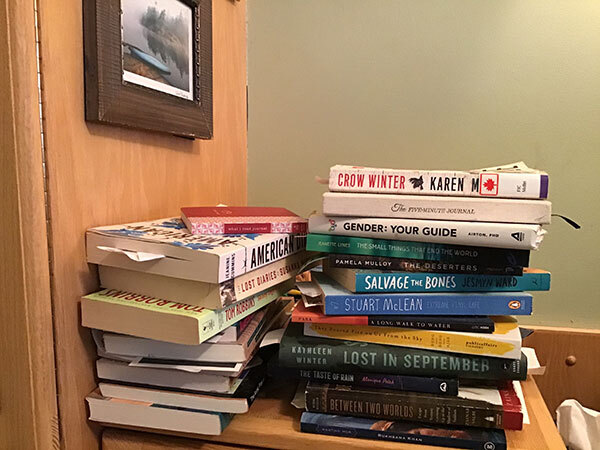

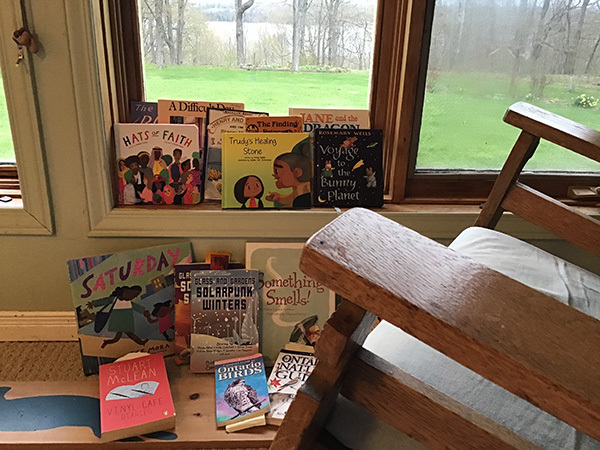

Books have been my comfort food, teachers, and medicine—I return for remedies when I am hurt and lost in the dark woods of my wounded self. Memoirs are sacred texts: I didn’t receive the “How to be Human” guidebook at birth, and I misplaced the “Here’s How to Fix This Mess” memo, so I turned to other writers to learn. My goal wasn’t to humiliate anyone, but to make order from the chaos.

Now, to the mother question. Conventions around how to talk about mothers are so strong—there’s a special place in hell for women who complain about our mothers. And yet, the “poorly mothered,” as Linda Clarke puts it—a long list of writers that includes Mary Gordon, Mary Karr, Jeanette Walls, to name a few—have pushed back on society’s assumptions about how daughters should behave. You could say these writers have placed truth above relationship. Or that their relationship with truth outweighed a conventional sense of duty to the mothers. What are your thoughts on this dynamic?

Uhm, first of all, thank you for putting me in incredible company—took a moment to swoon and pass out. I’m back now. That special place in hell has a room reserved for the ungrateful daughters of Italian mammas (down a rocky corridor route, past huge cisterns of molten lava, and low-hanging stalactites, turn left). To be a mother in Italian culture is to be a member of an exalted, celebrated group, and to a certain crowd my mother outranks me in respect simply because she became a mom—even though she was astonishingly unsuited for the role. On my maternal side, three generations of mentally unstable behaviour were recorded, and I’ll never find out how far back the strain extends.

Clearly, the situation is far more complex than individually being unmothered. Not long ago, Italy had the highest rate of femicide in Western Europe. At the intersection of imperialist Roman Empire Avenue and Monolithic Catholicism Boulevard (aka Ground Zero) thrives the blight misogyny. It wouldn’t be fair to explore my difficult mother or the lingering harsh impact she had without acknowledging the deeply flawed world that formed her. This requires a collective societal reckoning: until we can stop reading articles about domestic violence that state “The catalyst was an argument—”, and understand that brutality is frequently a precursor or predictor of catastrophic events—nothing will change.

Family violence is another taboo you tackle, revealing stories that implicate you in the household cycle of violence. Wasn’t it exhausting, having to recall those scenes? How did you prepare yourself? And how did you survive the writing?

Absolutely, the process tuckered me out. My feeling was, the only way to be fair was to show the devastation we wrought together and the part we all played in our disastrous union. We dealt with each other day-in, day-out with warts, blisters, and all on display. Imagine sitting down to dinner with family and the equivalent of an old-style pull station fire alarm goes off. The device never stops blaring, and no one arrives to turn off the noisy contraption. Everyone shouts over each other to be heard, nerves unravel, and the conduct is unbecoming to their humanity. We were a family in constant crisis—no one behaved their best.

When the process wore me out I checked in with friends, ate comfort food, and practiced the avoidance skills I had acquired and perfected in childhood. At times, unhelpful coping techniques were my best defense against the vociferous inner critic who berated everything I wrote. The hindering strategy I reference is code for copious amounts of sugar. I’m talking about an outrageous intake of sour key candies.

Please, say more about self-care.

Please, say more about self-care.

Of course, it would be an honour. I don’t think self-care is discussed as much as the subject is needed. And I want to be cautious with the topic because a well-being routine is as personal and unique as a fingerprint.

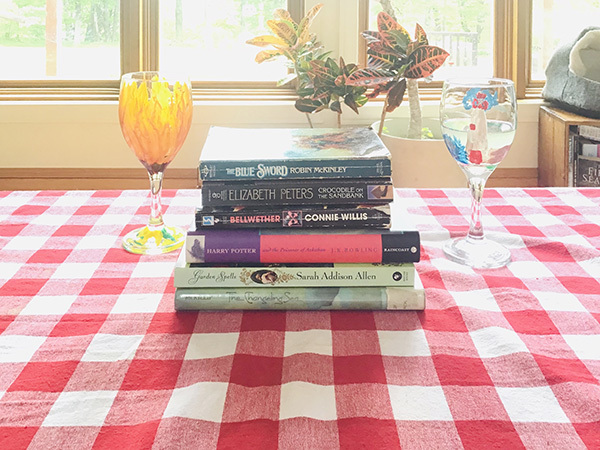

One thing I recommend to students is to make a self-care list of activities that soothe. Everything has to go on that list without judgment. Let me share part of mine to highlight what I mean: Cry. Consume chocolate. Call a friend. Slip under the duvet. Read. Drink a cup of tea. Have a glass of water. Eat spaghetti sprinkled with parmesan. Hoover potato chips. Shower. Order take out. Speak with dad. Watch Star Trek. Decorate a notebook. Sleep.

A self-care list isn’t the sole domain of creative nonfiction writers, but a form of dependable solace for anyone going through a difficult time—say, a pandemic. For years I felt embarrassed about the habit of viewing television shows I’d already seen or rereading a favourite book while others waited patiently in a pile for attention, but I’ve learned that the practice is common in individuals dealing with Complex-PTSD. The unsettled mind seeks stories with character arcs, plot lines, and endings that are already known as a source of comfort and calm.

Your mother and father are still very much alive. We know when we put down the book that the heartache is ongoing—that the mother-daughter story, in particular, when it does end, might not end well. What are your thoughts on how to tell a story that is still in motion?

This was the biggest hurdle for the longest time in large part because I bought into the self-help myth that one could change their station in life with hard work and adjust their busted self through serious effort. My father fervently believes people can pull themselves up by their own bootstraps, and while I don’t agree, I still battle that beast. When I poke holes in the expression, he admits it’s untrue. Barriers exist that we can’t fathom, but we must.

In my distorted thinking process, it might have been acceptable to end with our story “still in motion” if we had an overall successful finish. This is where buying into the self-help myth is a form of interior pollution, and I think it’s also where the demand for inspiro-porn comes from; a dark and troubling tale is permissible if everything works out favourably in the final scene: readers trust everything will be “better in the long run”—everyone altered forever but wiser for the anguish they endured.

That false equation of suffering-plus-survival-makes-people-stronger simply indulges the broken systems within society while placing the blame squarely on an individual’s shoulders. It’s absurd and corrupt.

Resilience depends more on the support we receive than on our inner mettle. Anyone who says different is peddling snake oil. In reference again to the pandemic, the popular saying, “We’re all in the same boat,” was making its way across social media a few weeks ago. Thankfully, people pushed back noting that while we are weathering the same storm it’s sheer ignorance to assume we’re all in the same boat. I mean, how was that not obvious? Some people are in sailboats, some individuals will ride out this squall in yachts moored securely in a marina, some hoodwinked folks claim to miss the cruise ship adventure and many, many more are bracing to get through this tempest in life rafts or gondolas or worse—already clinging to flotsam and trying to keep their hope above water.

One of the things I love is how you handle class and dialogue—moving seamlessly between Molisan and English. Ocean Vuong talks about recreating working-class, immigrant bodies and voices in his novel, On Earth, We’re Briefly Gorgeous—he sees himself writing in the tradition of Melville, another local New England writer who took the working class (in his case, whalers) seriously enough to document their lives. Vuong places his work in a line he traces straight to Moby Dick. Immigrants, in art, are so often marginalized, invisible, yet in Vuong’s works they are lifted up, placed squarely in a literary tradition where they belong. Any thoughts as you reflect on this?

One of the things I love is how you handle class and dialogue—moving seamlessly between Molisan and English. Ocean Vuong talks about recreating working-class, immigrant bodies and voices in his novel, On Earth, We’re Briefly Gorgeous—he sees himself writing in the tradition of Melville, another local New England writer who took the working class (in his case, whalers) seriously enough to document their lives. Vuong places his work in a line he traces straight to Moby Dick. Immigrants, in art, are so often marginalized, invisible, yet in Vuong’s works they are lifted up, placed squarely in a literary tradition where they belong. Any thoughts as you reflect on this?

Trying to capture my father’s voice and do him justice was another craft element that would swirl through my neural pathways late at night when I was trying to work out chapters and sequences. I love accented English; honestly, I cannot get enough of that glorious speech choir one can hear on the subway in Toronto. I love the made-up words of the first generation (a vocabulary that often is lost or erased when their descendants learn to speak the “proper” language of their ancestors).

All my life, I watched people treat both my parents as if they were unintelligible simply because they had thick accents even on words that could be easily deciphered. Listening is a lost art. Combined with my intense dislike of snobbery, I was determined to include untranslated dialect that I hoped readers would understand by dint of context, and include some dialogue where we switched from our rural Italian dialect to English because that is how we converse. To state the obvious, accents are different on the page; the whole endeavour can come off sounding fake, or like a gross stereotype. I was confident readers would discern that the solid English sections of dialogue was in fact Italian. And when readers quote my dad’s botched idioms, I feel honoured that his charming expressiveness continues on.

In Amy Tan’s fantastic essay, “Mother Tongue,” she addresses the problems with calling her mother’s English “broken,” “fractured,” or “limited.” I decided not to use those terms anymore because they were pejorative.

I speak mangled Molisan, and have been mocked for mistakes many times. I persist because I’ll lose this first language when my father is gone. Since he’s retired, my dad’s grasp of English is weakening and worsening. Let’s just say, I’m translating more medical appointments. This is how communication works—always in a state of flux.

In one sense, your memoir is the paradigmatic ugly story/beautiful art phenomenon—and yet you resist notions of the classic redemptive arc. You’re willing to challenge the notion that if the Truth (capital T) is told with heart, all will change magically for the better.

Life is messy in general. With a chronically ill loved one (even estranged) and an abusive past, so many days felt like I was juggling with fire and dropping a bunch of lit torches. The auspicious aspect: my publisher Mona Fertig was sending gorgeous designs of the book cover and encouragement from afar. Time flies when the calendar contains a deadline.

The week after the launch in Toronto, my father went to the police with my aunt to attempt to put another restraining order in place. Peace bonds lapse, but abusive behaviour isn’t a carton of milk—there’s no expiry date. At the station my dad told the officer the situation was so bad, his kid wrote a book about her mentally ill mother. He produces the memoir and insists the account proves he was right all along—my mother is impossible, unbearable, and relentless. Remember: he hasn’t read the book and likely won’t, so he fantasizes one character the villain, when in reality our circumstances often brought out the worst in each other.

Peace bonds are ridiculously complicated to enforce. I’ve thought about getting one, but my address would be required and I live in hiding from my mother. I’ve been lucky no one has given away my exact whereabouts; my mom is aggressive and exhausting in her search for me. There is no such thing as closure (another myth), and after taking so long to realize I would never officially “get over” what happened (an objective for many years), it would have been irresponsible to say I came out of my childhood, the ongoing battles with my mother, and the experience of writing a memoir a stronger, better, more improved version of myself.

Families don’t always survive their trauma. They implode, shatter, and disintegrate—home is lost but the painful memories prevail. Acceptance is a calm day with a light breeze, meeting a friend for a meal and observing a glorious moon over the city. I can still be grateful for the life I have without engaging in a thinking process that supports victimizing other women or the most vulnerable communities among us. It takes vigilance.

Recently, I reread the ending, to recommend it in a memoir course, and found myself bursting into tears. “No longer troubling deaf heaven with bootless cries, we might look upon ourselves and bless of the sum of all who came before us…” The closing lines are shatteringly beautiful and deceptively simple. How did you resist the pressure to say “everything’s fine now,” the temptation to say that all the terrible things that happened were simply gifts that made you appreciate life even more?

My heart! That is so generous and I’m deeply grateful. Even while I grappled with self-help mythology or the pressure to produce inspiro-porn, I was acutely aware that our story would be erased from the world if I didn’t endeavour to be as precise as possible about how difficult it was, and how troublesome it remains. And I was fortunate to have strong readers, excellent advisors (including you, Susan) and to work with a wonderful editor who helped as well: Pearl Luke.

What’s next in your writing life?

A collection of lyric essays, Let Not Your Heart Be Troubled, and a series of linked stories titled Mangiacake.

And finally, how about some hard-won wisdom. The Paris Review has a column called Rx: readers write in with a problem (pandemic, lost job, death of a beloved), and a resident poet prescribes a certain poem with that heartache in mind. Naturally, you should have your own column, but for now, what would you prescribe for writers who are struggling as you’ve struggled?

Read Michael Ungar’s article in The Globe & Mail, “Put down the self-help books. Resilience is not a DIY endeavour” as an antidote to gaslighting (and then carry on with Rebecca Solnit’s writings and keep going). Seek out community. Help everyone you can when you are able to do so. Find free online workshops or classes. Read Mary Oliver’s poem “Wild Geese,” and minimize your time with harmful people. Keep a safe distance. Memorize this line from Max Ehrmann’s Desiderata: “You are a child of the universe no less than the trees and the stars; you have a right to be here,” and aim to embody this truth every moment of your precious life.

Eufemia, thank you.

An absolute pleasure, Susan, thank you.

Let’s talk about patterns. Certain issues haunt nonfiction writers: how to depict people in ways that are truthful, authentic, but not hurtful; how not to exact revenge; how to avoid diminishing or punishing your characters. It’s the dilemma at the heart of making art from trauma. Your story digs deep into the family vault, exposing generations of harm, including a mother who is ill and suffering, someone who’s caused unending heartache for herself and others. How did you balance the enormous pressures that come with exposing family trauma with the tell-all expectations that come with writing memoir?

Let’s talk about patterns. Certain issues haunt nonfiction writers: how to depict people in ways that are truthful, authentic, but not hurtful; how not to exact revenge; how to avoid diminishing or punishing your characters. It’s the dilemma at the heart of making art from trauma. Your story digs deep into the family vault, exposing generations of harm, including a mother who is ill and suffering, someone who’s caused unending heartache for herself and others. How did you balance the enormous pressures that come with exposing family trauma with the tell-all expectations that come with writing memoir? Please, say more about self-care.

Please, say more about self-care.  One of the things I love is how you handle class and dialogue—moving seamlessly between Molisan and English. Ocean Vuong talks about recreating working-class, immigrant bodies and voices in his novel, On Earth, We’re Briefly Gorgeous—he sees himself writing in the tradition of Melville, another local New England writer who took the working class (in his case, whalers) seriously enough to document their lives. Vuong places his work in a line he traces straight to Moby Dick. Immigrants, in art, are so often marginalized, invisible, yet in Vuong’s works they are lifted up, placed squarely in a literary tradition where they belong. Any thoughts as you reflect on this?

One of the things I love is how you handle class and dialogue—moving seamlessly between Molisan and English. Ocean Vuong talks about recreating working-class, immigrant bodies and voices in his novel, On Earth, We’re Briefly Gorgeous—he sees himself writing in the tradition of Melville, another local New England writer who took the working class (in his case, whalers) seriously enough to document their lives. Vuong places his work in a line he traces straight to Moby Dick. Immigrants, in art, are so often marginalized, invisible, yet in Vuong’s works they are lifted up, placed squarely in a literary tradition where they belong. Any thoughts as you reflect on this?