Kim Jernigan in conversation with Terence Young on his poem “The Bear,” one of the winners in The Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest for 2018. The poem appears in Issue 148 of The New Quarterly.

Terence Young is a poet and fiction writer who lives on Vancouver Island where, until his recent retirement, he taught English and Creative Writing at St. Michaels University School. He is co-founder of The Claremont Review, an international journal for young writers, as well as an accomplished writer himself—and an inspired and inspiring teacher.

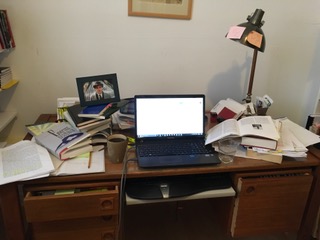

In 2008, he was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence, a national honour. “That Time of Year,” a story from his second collection of fiction, The End of the Ice Age, was selected for the annual Best Canadian Stories in 2012. The whole family is literary (his wife, the poet Patricia Young, has frequently been among the finalists for the Occasional Verse contest). The setting for his poem “The Bear” is taken from life, a property that has been in his family since the 19th century. The land, a small acreage, includes a barn that has been transformed over the years into a summer cabin, complete with cast iron bathtub, outdoor shower, and a 1939 Savoy Enterprise wood cook stove.

*

Kim Jernigan: When I wrote to tell you that “The Bear” was one of the winners in The New Quarterly’s Occasional Verse contest, you replied, “I have only recently returned to writing poetry more seriously and am a little uncertain about it. The contest, centred as it is around occasional verse, suits what I write perfectly, since I am by nature drawn to the lyrical narrative.” I know you’ve worked primarily in the short fiction genre and am curious to know how you understand that term in relation to both fiction and poetry.

Terence Young: Having been a teacher of English literature for far too long, I understand the term “lyric” as it pertains to poetry that is primarily the expression of emotion, usually written in the first person. Shakespeare’s sonnets are good examples, as are odes and elegies. Narrative poetry usually takes the form of ballads, epics, and romances. Coleridge and Wordsworth threw this distinction out the window when they published the Lyrical Ballads in 1798.

My first poetry teacher, George McWhirter, applied the term “lyrical narrative” to the kind of poetry I was writing for him while I was at UBC in the MFA program there, and I think it has always rung true. I tend to explore “occasions” for meaning, for personal significance, and because these occasions are often incidents, they end up taking the form of a story, one that, in its language, tries to convey not only a narrative, but also a tone: the attitude of both the speaker and the author. My impression is that such poetry is of less interest for readers of verse these days and that the musicality of language detached from any story is in the ascendant.

I read all kinds of poetry and am continually amazed by what I read, but when I write, it is usually the lyrical narrative that finds its way onto the page. As for fiction, story is still an important component, although there is a multiplicity of ways to tell stories, techniques that involve the manipulation of voice, chronology, setting, diction, point of view. Like many writers, I don’t really know exactly where I am going when I begin a story and am often surprised where I end up. But, as with my poetry, the effects of tone, language, and the tale’s structure really dictate the success of the final product.

KJ: The New Yorker, in their fiction issue of some years back, divided their pick of the best up-and-coming writers into categories by subgenre, one of which they dubbed “lyrical realism,” stories taken from life in which the language, particularly the imagery, lifted, or dignified, the subject matter. Think Joyce’s “The Dead.”

Yet your fiction, at least in The End of the Ice Age, seemed to me darker, grittier, more despairing. Then I came upon “That Time of Year,” a story about a long marriage, about aging, diminishment, and loss, which none the less lifted and comforted me. It begins, beautifully,

They swam on the last night of summer. The lake still held the heat of the day, and in the fading light bats swooped low over the water, hunting the few remaining mosquitoes. Tomorrow’s forecast was for clouds, possibly showers. There was a note of loss in the air, as there always was when the weather turned. It wasn’t just another rain coming. It was the shrinking year, the dark months, the retreat from joy. How many times could she do this, she wondered. It was like drowning. She almost laughed at the thought, afloat as she was on her back, looking up at the stars that multiplied in the deepening sky. But, no, that was exactly what it felt like. It was like going under.

I’m pretty sure the ghost of “The Dead” hovers over this sad/luminous story. Or maybe the voice of Virginia Woolf in To the Lighthouse? Whom would you put forward as your literary mentors?

TY: The story you have quoted takes its title from Shakespeare’s sonnet 18: ‘That time of year thou may’st in me behold/ when yellow leaves, or none, or few do hang.’ And, like “The Bear,” it is situated at our cabin, a similarity that demonstrates just how strongly that little piece of land figures in my life and the lives of my family. What I like about Shakespeare’s sonnet is the voice, the calm and honest speaker who offers three distinct images of his stage of life, each an image of approaching extinction, and how he argues rationally and forcefully that it is this transitory quality that should bind us even more closely to one another.

It is a lovely thing to stumble upon a character whose musings allow the writer to explore at his or her leisure such pressing questions. Certainly, Joyce in The Dubliners has a number of such voices, as does Woolf in her stream of consciousness meanderings. I am also drawn to the people in Haruki Murakami’s stories and novels, particularly the speaker in his novel Norwegian Wood. I even tried consciously to copy Murakami’s style for a couple of stories, so strong was the impression he made upon me. There are many other writers who have influenced how I write: Joy Williams, Lorrie Moore, Amy Hempel, Amy Bloom, Denis Johnson, Tobias Wolff. More recently, I am drawn to the clarity of someone like Rachel Cusk, who mixes fact and fiction so brilliantly, but also to the zaniness of writers like Karen Russell and Lauren Groff.

KJ: Every year the judges of the OV contest, friends and family of the man for whom it’s named, wrestle with the question, “What is Occasional Verse?” We’ve settled on two loose criteria: there must be an occasion, of course, and the poem should be addressed in some way.

Our sense of what constitutes an occasion is open-ended. Many of the poems received were written for a formal occasion: a wedding, a birth, an anniversary, a funeral. But others make an occasion of something ordinary by virtue of the poet’s attention. Examples from this year’s gathering: a man sweeping snow off a rooftop antennae, a child responding to his father’s query about what he dreamt that night, a mother doing a crossword puzzle with her grown daughter. The addressee of the poems (we often imagine these poems being read aloud, and indeed read them aloud ourselves as part of the adjudication process) is sometimes made explicit, as in Suzanne Nussey’s “For My Husband on Our Anniversary,” but other poems are addressed slant: to a daughter, to another poet, to a civic “we”, or to the dead.

Your poem “The Bear” takes as its occasion a bear raiding a garbage can on a wooded lot that’s long since been encroached upon by the city. Sighting a bear where you don’t expect one is an occasion, for sure, a brush with mortality, but the chief interest in your poem, or so it seems to me, is as much in the addressee, “you,” initially some version of the poet’s own self. But there’s a nifty shift at the end from the poet registering his experience as it unfolds to his imagining how he will polish the story for sharing later around the dinner table.

My father, after whom the contest is named, was a natural raconteur. I was always amazed, listening to him tell a story about an adventure I’d been party to, at how much more wonderful, meaningful, or apt the story was in his telling. Do you also rise to an audience, or do you prefer the distancing mechanism of the page? A little of both? You are, of course, a teacher as well as a writer, but what was, for you, the added value of concluding the poem with that imagined retelling, a second occasion to cap the first?

TY: I’m pretty sure many people, despite whatever inconvenience, danger, annoyance they may be experiencing at the time, consider the possibility of embellishing the episode later to a friend or friends around a dinner table or at the pub. We are very “meta” in that regard, both living our lives and imagining at the same time how others, even ourselves, may view them later. Facebook and the art of the selfie may be to blame for the latest obsession with how our exploits are perceived, but I have no doubt that the storyteller in all of us and his or her penchant for elaboration has been with us for a long, long time.

It’s also interesting that some stories do not lend themselves to such artistic interpretation. My father loved to tell stories, for example, but he would never speak of the war. Clearly, it needed no enhancement and was something he preferred to forget. Like my father, I also love to tell stories, and teaching was a great vehicle for combining literature and personal experience. I once had a student come back to tell me many years later that a story I once told about my high school years, during which several of us at one point dared another student to jump out the math class window when the teacher’s back was turned, had actually gained some personal significance for her, for she had married the son of the jumper. The connection did not become clear until she innocently brought up my story at dinner one night, and her new father-in-law, astonished to hear about the incident so many years after the fact, revealed that that story was actually about him, attested to its truth and to the fact that he had broken both ankles upon hitting the ground. So, yes, I do indeed rise to an audience, and the poem about the bear has been told many times with many variations and emphases.

For me, the conclusion of the poem seems in keeping with magical qualities of the bear itself, that the appearance of such a creature in a place where none had been seen for over half a century should rightfully become the stuff of legend. And what better way for a legend to start than among friends during a meal.

KJ: I’m also interested in how you conceived of the character of the bear, a combination of clown and adversary.

TY: Rightly or wrongly, when I first saw him, it was hard to think of the bear as anything other than comical, seated as he was with his head in the plastic garbage can. He might have been an act from the circus, he looked that silly. Close as I was, too, I was able to see quite clearly how lustrous his fur was, what a young and handsome creature he was. Having worked in the bush, however, I knew also that it was not wise to anthropomorphize these animals, that they are unpredictable and powerful. And I was instantly aware that something had changed, that the mere sight of him had altered the woods around us.

KJ: So many of the poems received for this contest concern issues or life experiences that bring up emotion on tap. So we are always asking ourselves where is the craft? To what extent is the impact of a poem owing to the poet’s handling of form and language as opposed to the claim of the occasion itself? Can you speak to some of the techniques you used to shape the story you wanted to tell, or perhaps to understand, yourself, its significance, in the moment and after?

TY: I have to say that I’m not really conscious of technique when I am writing. I’m mostly looking for the right form—in this case the couplet—and the narrative flow of the poem, how it moves from moment to moment. I’m also trying to identify exactly what it was about the experience that affected me. To see a bear is one thing, but to see one in such proximity after a sleep when one is still in partial dream state is a different thing entirely, and if there is anything worthwhile in a poem, it must come from a true rendering of the emotions and thoughts that generated it.

KJ: I appreciate what you are saying, that if the form is too insistent, too self-conscious, the whole thing can collapse under its own contrivance. But I still can’t help but admire how “The Bear” works: the couplets are a visual equivalent of the opposed realities—man and bear. But lest that become facile, only the first two—when taken together, a kind of establishing shot—are end stopped. The next sentence runs a little over five lines, ending mid-line, as also the third. But the fourth and final sentence runs to twelve lines, a great rush of words that, subliminally at least, suggests the adrenalin rush of the encounter.

Then there’s the poem’s ending. Earlier, you included Lorrie Moore in your list of writers whose work informs your own. She has said that “[t]he end of a story is really everything.” It’s often not the chronological ending, “but it gives the whole meaning to the story.” I think the same could be said of a poem, so I felt a particular joy at imagining the ah-ha! moment when your raconteur self seized upon the perfect simile with which to end his story, a description of “…the garbage can’s rectangular lid and four neat punctures, / arranged in a fan, an arc, like a winning hand of poker, jokers wild.” Jokers wild! That’s the experience in a nutshell, the poet’s cautionary note to self: a bear, no matter how clownish he looks, can snuff out a life with the swipe of a paw.

Okay, two last questions: The initial encounter ends with the narrator/poet following the bear “axe in hand.” So I have to ask, “What the heck were you thinking of doing with that axe?!!” And what are you thinking of doing with your prize money?

TY: As for the axe, some part of me was aware that Trisha was down the road gathering blackberries, and I think I felt I had to arm myself in case he headed in that direction. After he disappeared, I ran as fast as I could to where Trish was and did my best to convince her calmly that she needed to return to the cabin. The axe was still in my hand, so I believe she picked up on my urgency.

The prize money, on the other hand, no longer exists, which is to say that I spent it as soon as I heard about the poem’s success. Since our most recent indulgence was a trip to Spain and Portugal in September and October, I think it’s safe to say that it helped us to more than a few delightful Spanish and Portuguese meals, possibly even some wine.

*

Interviews with Past Contest Winners:

2017: Fiona Tinwei Lam for “Test”

2016: Ruth Daniell for “Wedding Anniversary”

2015: Cori Martin for “Quilters”

2013: Suzanne Nussey for “Poem for the First Sunday of Advent”

2012: Anne Marie Todkill for “Non sequitur”

2011: Kerry-Lee Powell for “The Lifeboat”

2010: Jeanette Lynes for “The Day John Clare Fell in Love (1818)”