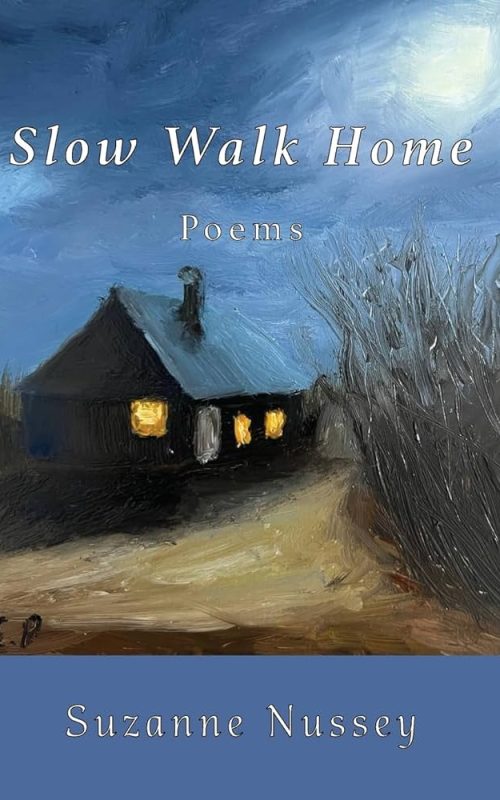

In the tradition of poetry collections that gather work from a sometimes extensive diversity of themes, styles and poetic preoccupations, the book is divided into three sections, ‘My Father’s House,” “Life Skills,” and “Safe as Houses,” each title based on a key poem and designed to capture the dominant theme or mood. Any reviewer can choose to focus on poems that they find particularly effective and moving, as I intend to do but I would also like to take advantage of my editorial familiarity with these poems to note what has happened to them between journal and book publication, that is, to see what she has revised, the obvious part, and why, a more speculative endeavour. This is what is meant by “versions of these poems have appeared…”—a ubiquitous phrase in many an Acknowledgements page.

The most dominant presence in the poems in the first section is, of course, the father and the family, but another unifying element, at least in the poems focusing on the poet’s girlhood, is Nussey’s way of conveying her innocent perception. As the poet asks in The New Quarterly’s “Finding the Form” on-line series of essays, “How do we recall something that wasn’t actually an event, was more of a transition…How do we reconstruct something we did not, at the time, have the language to describe?” We see such innocence in “What Comes of Picking Flowers” when the young daughter finds newly picked gladiolas resting in pails of water in her father’s shed. Unaware that they are intended for a wedding at the church where her father is pastor, she replants them in “rows of rebel angels/until his garden blossoms brilliantly again/and I see my work is good.” Hearing the mother’s angry words, about the expense and inconvenience of replacing them, consequences beyond her naive conception, the girl retreats to the nearby forest to watch her father discover her well-meant but futile floral arrangement in his beloved garden; she expects anger but he “steps back and shades his eyes./ He sees me and then/he laughs.” Nussey’s achieves the same effect even more forcefully in the collection’s title poem, which recounts the father’s front-porch visits, accompanied by his daughter, to his parishioners, elderly women, “their silver hair coiled/into mesh-capped knots,” smelling”of “soap and talcum.” The poet notes that there is “something in their faces I do not recognize” and on their way home, her father “names for me/the things I do not know./Shepherd. Sparrow. Oak./Blossom Widow.” A few changes have been made to this poem, the most conspicuous being its title, which was originally, “Morning Walk, Summer 1956,” a title that offered the benefit of specificity but lacked the symbolic significance of the replacement, “Slow Walk Home,” which suggests the gradual dawning of awareness and the comfort to be had in the soon-to change certainty of home or, as Nussey describes it, “This day/an empty tablet not yet tipped/toward calamity.” Instead of “We walk from the parsonage” we now have “From the parsonage we walk,” a reversal that gives the ordinary action more formality. “Freshly painted porches” has been revised to “thickly painted porches,” which hints more clearly of age and the continuing efforts to mask appearances. Other changes eliminate unnecessary details or redundancies: “their silver haired coiled smartly” reads better when the superfluous adverb is removed; the lines “a black dog chases, barks, but does not bite, my father promises” are more effective when economically reduced to “He promises the black dog barking will not bite.”

Another excellent poem in this section has been retitled to better effect. “The Black Fan,” as it was titled in its TNQ appearance, has been altered to “The Magic Fan,’ which coincides more powerfully with the primary intent of the poem, which provides a study in contrasts between the church, stifling both literally (the oppressive heat) and perhaps figuratively (the orthodoxy of worship), and the manse next door, where imagination roams more freely when the children’s mother brings out her exotic black fan and sings in a “voice she never brings next door, ” a song in which the hypnotically waving fan “will vanish summer/and winter and spring/ and then the worn out year,” sending her offspring “wandering into the fantastic night.” There have been other changes made to this poem, mostly minor, but none is as mood-altering as the reworded title.

All of the poems in the second session, “Life Skills,” are praiseworthy in their own way. Of particular note is “On your way out, please close the door behind you,” a facetiously titled but somber poem about our inevitable decline, the inescapable entropy of being human. The poem begins with the lines “Everything works its way/to naught/relentlessly as surf on stone” and ends by reminding us that “the body/becomes nothing/but another/body’s/thought,” the final lines of each stanza aligned as if the words are drifting off the page, the way, perhaps, we all slip out of life.

To return to the secondary focus of this review, the details of revision, let me focus on a poem that I first fell in love with in its original form, “Toward My Mother,” an attempt to paint a poetic portrait of a woman whose inner life and personal conflicts her daughter knew too little about. It is, in a sense, a lamentation that will resonate with any son or daughter who has taken their mother for granted. The poem begins with “What She Said,” a litany of motherly maxims and mythical advice like “always leave home in respectable underwear in case you are taken to hospital suddenly.” The poem then reflects on the extent to which these firmly entrenched but easily dismissed adages have influenced her own behaviour and attitudes, including the fact that she owns “ten pair of cotton underwear” and still spits out seeds she was told as a girl not to eat as they would take root in her stomach. The second part of the poem, “What She Never Said,” consisted in its original version of only five lines: “I am lost./ I did not listen/and have lost you/again.” The book version condenses the first twenty-two lines into one italicized stanza without punctuational pauses, as if to approximate the collective impact of this rush of memories. The end repeats the mother’s statement, “I am lost” but then adds several significant details about the unacknowledged realities of her mother’s life: “Her talents/under-estimated unsung/unrecompensed.” The final lines suggest a change of emphasis : “I did not know/how to listen/and cannot find her now.” The difference in the endings lies perhaps in the difference between hearing and heeding, the inability to listen rather than the refusal to do so, something not lost irretrievably but simply not yet found.

Another interesting change in this section of the collection involves separating what was a single three-part sequenced poem in TNQ, “Life Skills,” into three distinct poems interspersed among the others in a way that both emphasizes and isolates their impact, not to mention giving the impression of development over time.

The choice of title for the third section, “Safe as Houses,” is thematically appropriate as a number of poems deal with house and home, leaving and returning to it, and death, which for some is considered a spiritual coming home. At the same time, the title is sadly ironic as the safety of home is only temporary or impossible, as reflected in the title poem, “Safe as houses: A litany,” which ends with an image of old women in Ukraine weaving “camouflage nets/to mimic green leaves/in spring, yellow/ in fall, dirty snow/in winter.” There is also no hymns-and- angels certainty surrounding death in a poem like “Selfie with Jesus: End Times,” which speaks of the contrasting experiences of the poet’s “godly aunts,” one of whom was asked to dance by Jesus as she came close to dying, the other “harrowed” by demons on her deathbed. The latter memory has the speaker seeking reassurance from Jesus, a sort of password, “something just the two of us/would know. What I said to my father/the day he taught me how to walk/alone.” Fortunately, there is a kind of reassurance offered in the book’s final poem, “Last Request,” which recounts the last hour of the poet’s dying father, lying in a hospital bed, kept alive by a respirator. As a departing gesture, “He pencilled in unsteady script/on a paper slip /his hardest words of all/Don’t be afraid.”

In addition to praising an accomplished collection of poetry in a literary environment where so many works compete for attention, I also wanted to focus on the common poetic practice of revision, especially as it applies to Nussey herself. As an editor, I know that many poets are incessant tinkerers, wanting to hone their poems to an ever elusive perfection. Many have not been able to resist the temptation to add, alter, or excise lines in poems we have already accepted. So it is hardly surprising that many a change is wrought between journal and book production. I wonder what happens when poets gather poems for a selected edition.

It occurs to me, belatedly, that I have not focused on an integral thematic and emotional element clearly evident in these poems—the significance of the spirit, especially in the Christian sense, the difficulty of maintaining faith, both an acceptance of it and a rebellion against it. These are all relevant to the mission statement of this book’s publisher, Saint Julian Press in Houston: “As a creative imprint, we aspire to identify, encourage, nurture, and share transformative literature and art of past and living masters.” Transformative— I can’t think of a better way to describe Suzanne Nussey’s first collection.