Finding the Form with Pamela Dillon

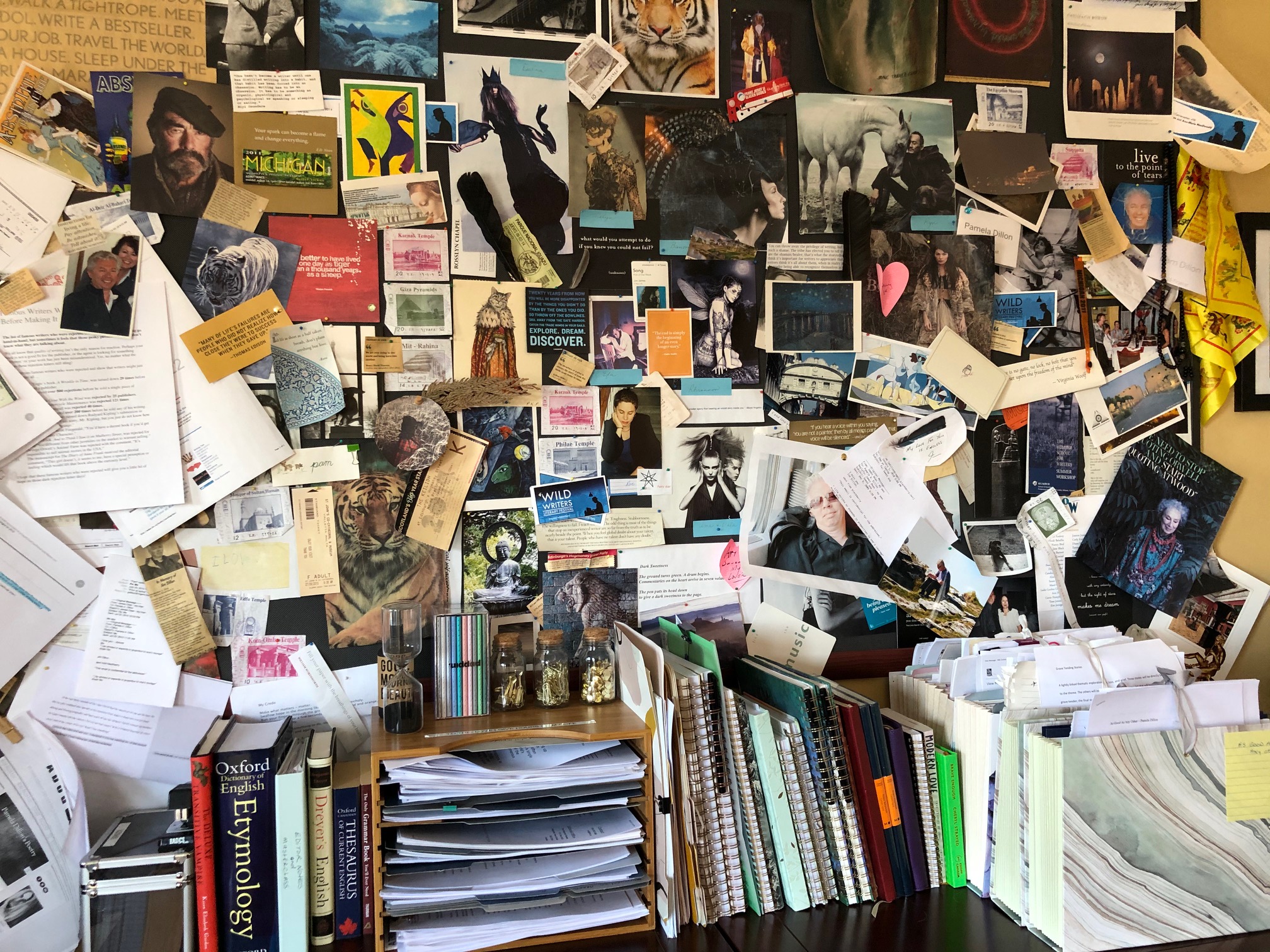

I rarely start with form unless I’m intentionally writing poetry; most other prose begins with a session of free writing. In the days when we were able to wander and sit in cafés I often spent a couple of mornings a week in a coffee shop journaling.

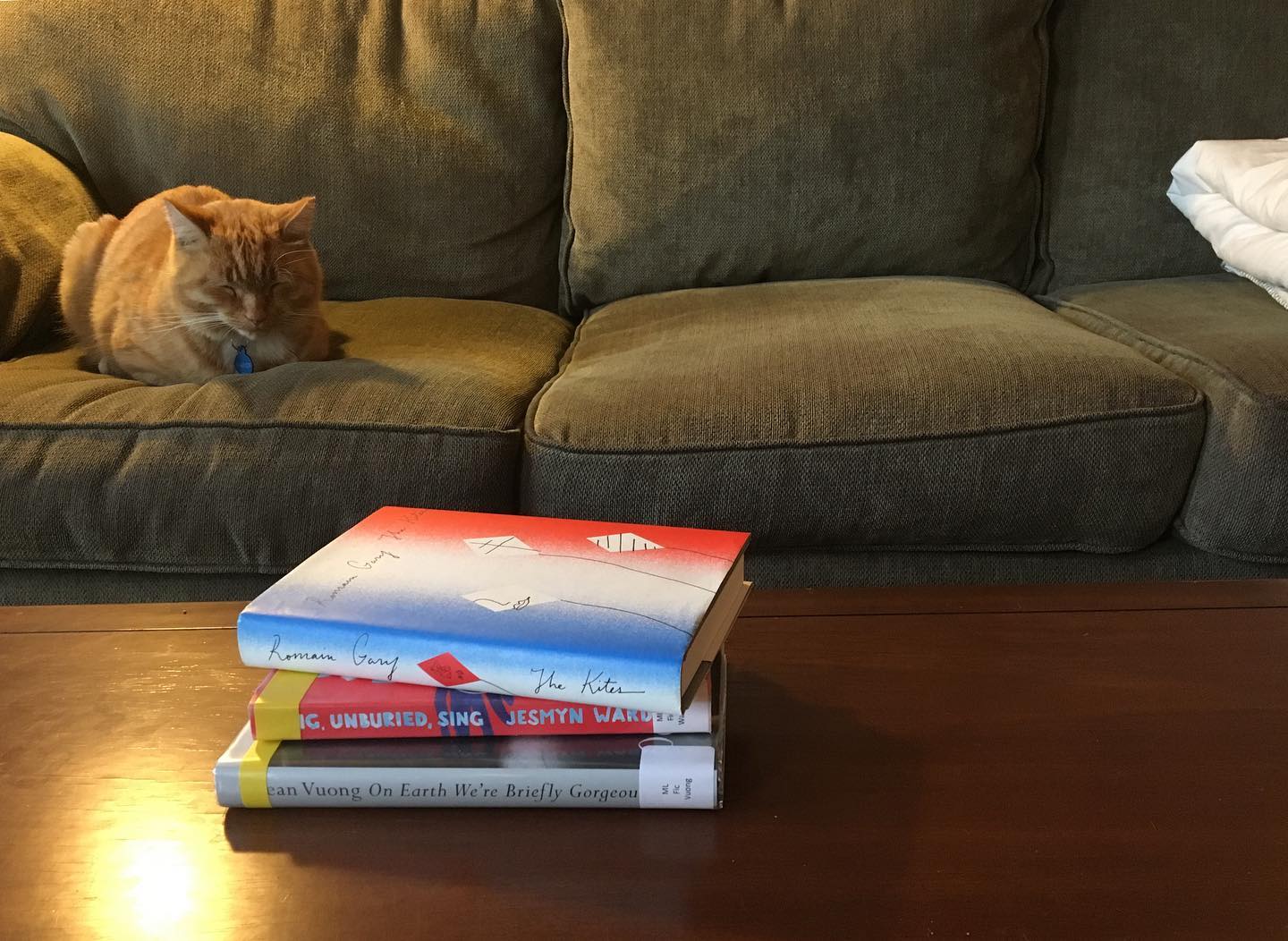

I remember playing with the idea of a poetic form for this story, something akin to a Pantoum poem with repeating lines. In the case of “Murmuration” I started the first sentence with the phrase—“I remember . . .” I thought I would repeat that line at the beginning of each paragraph.

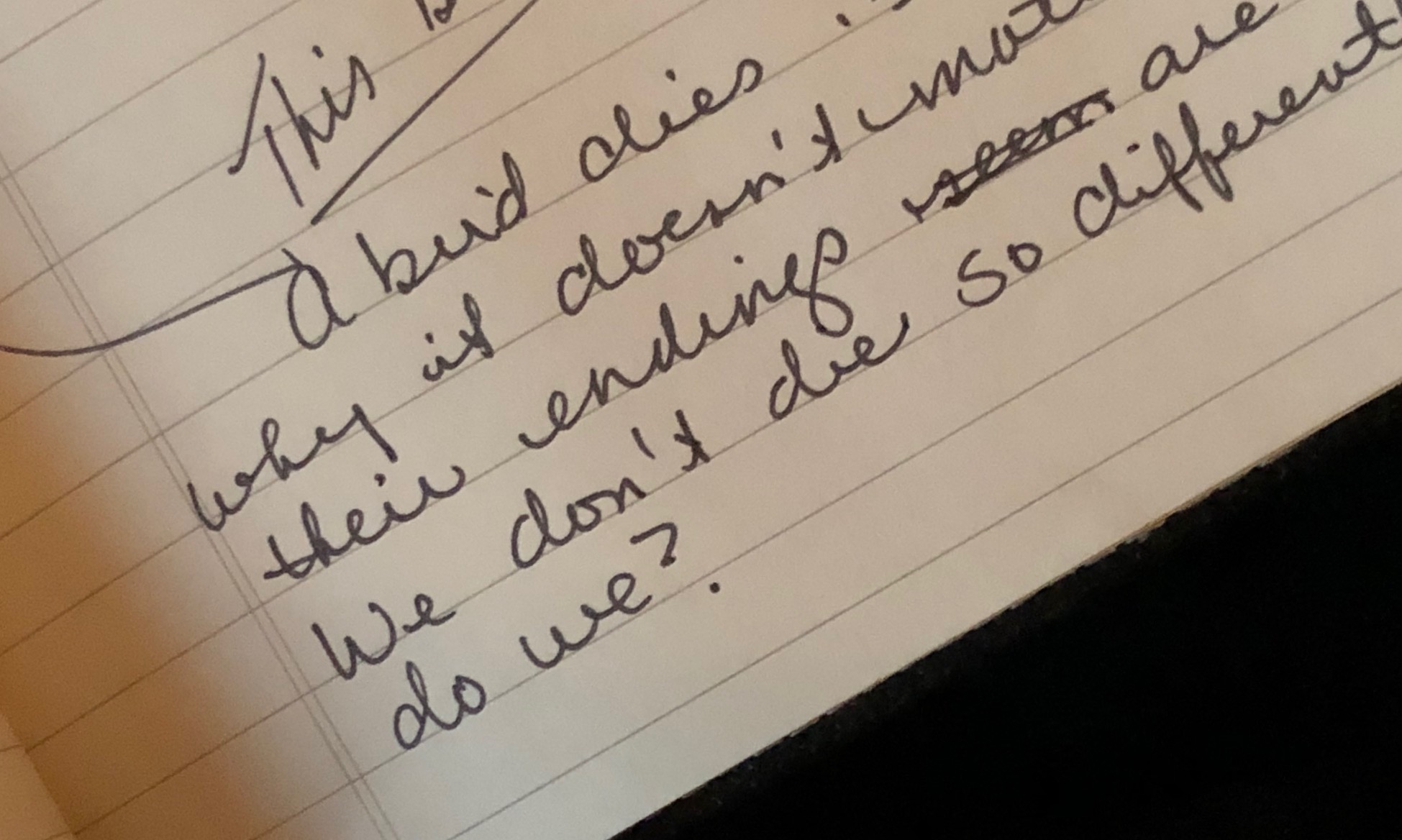

The beginning of the story is dark. I wanted readers to feel a sense of a future as though the protagonist was looking back from a better time. However, as I went on the repeated phrase began to feel limiting and it necessarily fell away during the editing.

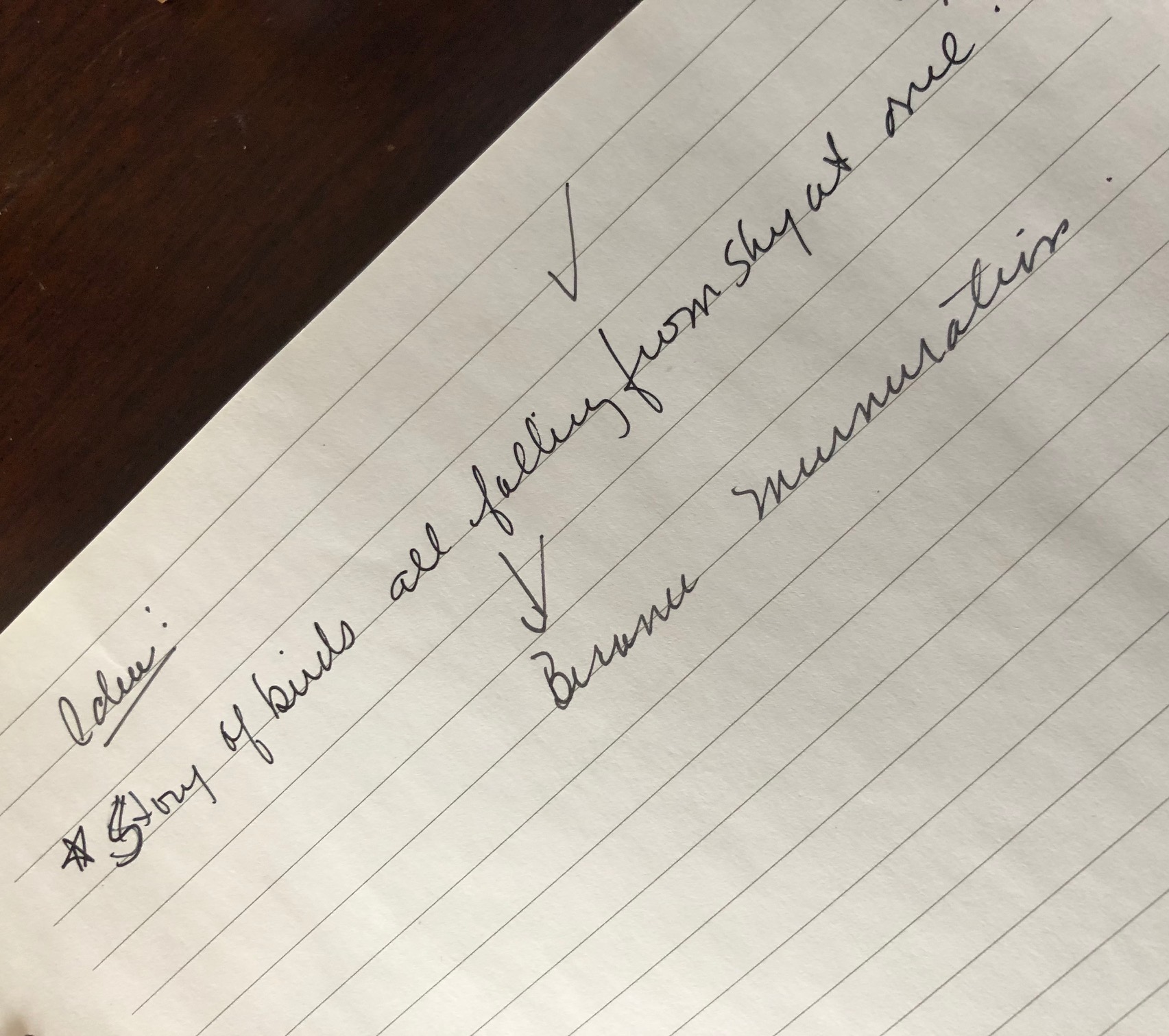

There were a few themes that interest me within this story:

- What makes some people respond to a crisis with hope, and others with nihilism? Why do many relationships seem to pivot between these two worldviews?

- I thought a lot about the romantic notions we have of nature and our place within it. Rather than being a part of nature we often seek to master it. I thought I might try to mimic this in the relationship between the two characters. In “Murmuration,” it’s Ava who seeks to master the relationship and Jenna who observes it.

It also made me think about the ways we learn to live with an uncontrollable event. What conflicts arise? Yet, I hoped to contrast the notion of conflict as revealed with Jenna and Ava, and acceptance with the brief appearance of David and Liliane at the end.

- I also confess to a fascination with murmurations. I’ve been lucky to see a few large flocks play out this strange dance; I’ve also watched a few dozen on YouTube. One day while watching a particular murmuration video I wondered if the birds ever crashed into each other or hit the ground. That question really captured my imagination. Of course, I had to find out and went down the rabbit hole of the Internet searching for that answer which then led to an imagining of the opening scene.

I wrote “Murmuration” in 2018. Of course, I had no idea that we’d someday be in the midst of a pandemic. I’m grateful to have this story published now; perhaps it’s the best possible time. I truly believe the story finds the writer and its moment.

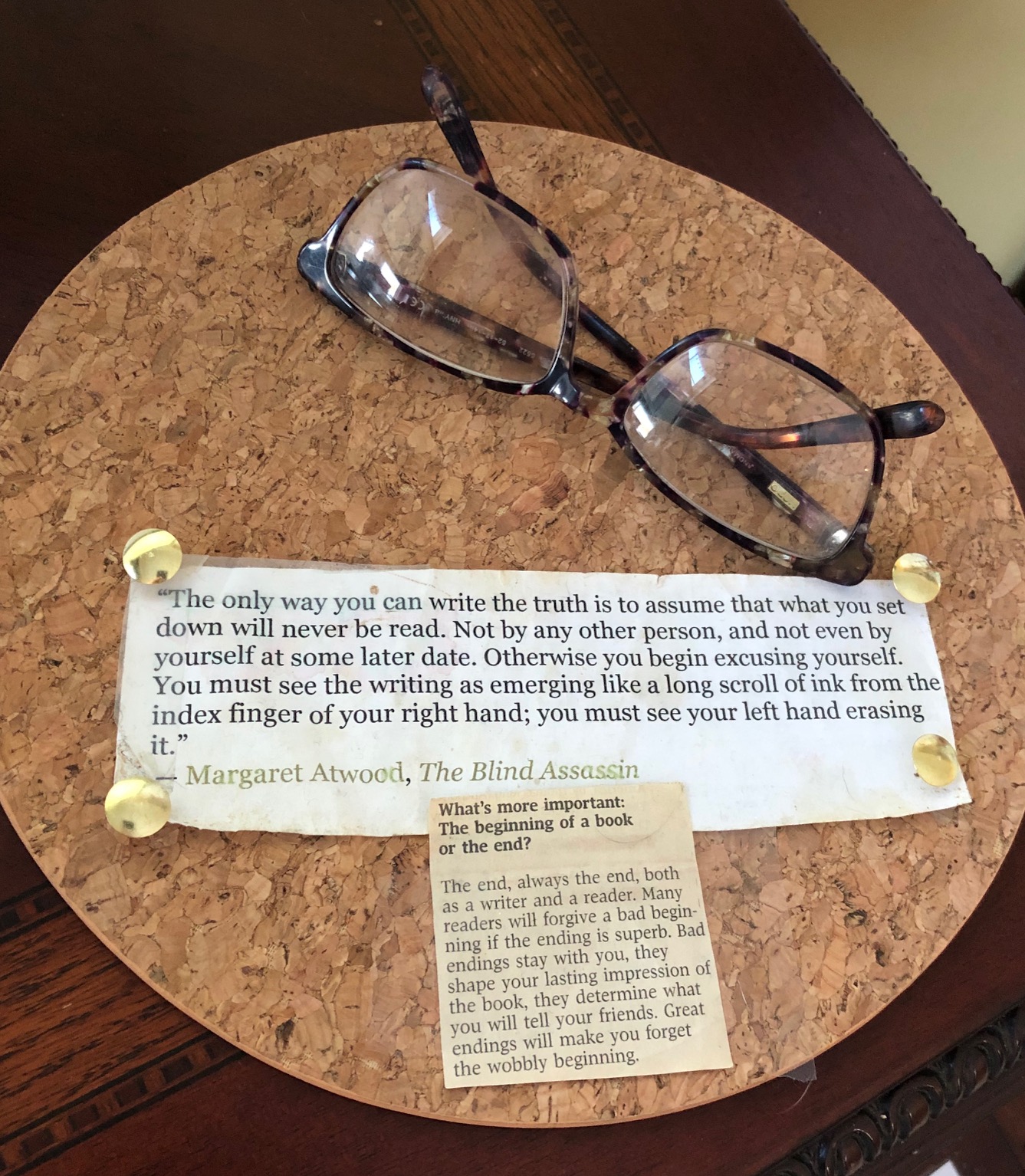

I’m most comfortable with fiction, and I’ve always thought of short fiction as considerably harder to craft. I find writing short fiction the most satisfying because the story has to be tight and there needs to be a firm grasp on the characters; it also requires a clear through line from beginning to end. I’ve become comfortable with this closer view.

I’ve played with stories that move back and forth in time; it’s something I feel can be done well though I’ve not mastered it yet. I’m also working on a story with the narrative voice in the second person. I love inviting the reader into the story I’m creating; I love the immediacy of it. It’s exciting to play with the point of view and see what works.

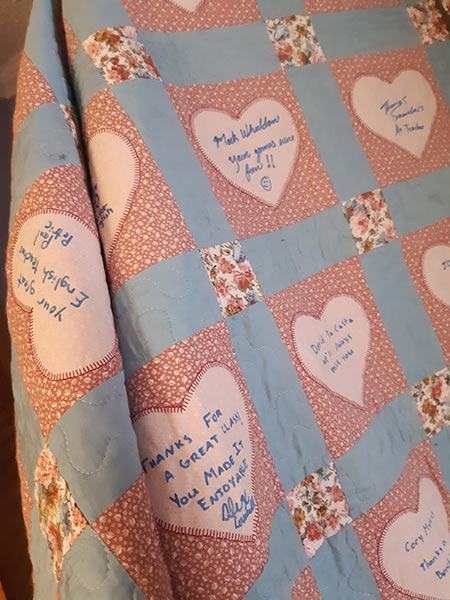

I must add that I’ve a lovely relationship with an editor whose questions and comments I trust. Writing can be lonely work, it helps to have someone with whom you can share your work in progress, and who doesn’t think you’re odd when you speak of your characters as living people.

Pamela Dillon is a writer, poet, and graduate of creative writing from the University of Toronto. Pamela’s publications can be found on literary websites and print journals including the CBC Books – Canada Writes, and The Globe and Mail. She is currently working on a collection of short stories.

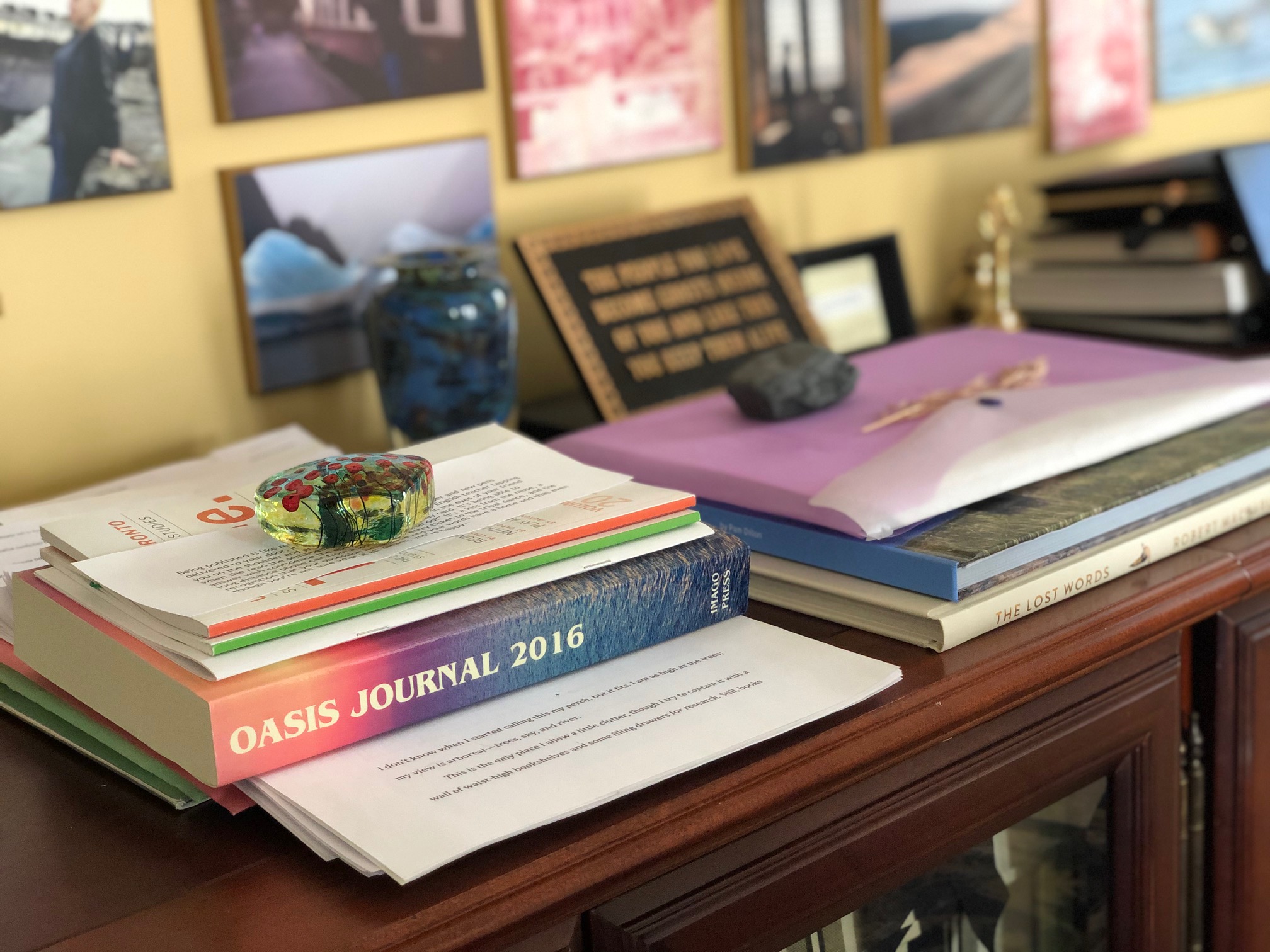

Photos courtesy of Pamela Dillon.