A Tribute to Jean Becker and Mino Ode Kwewak N’gamowak

Pungent smell of burnt sage. Haze in the air. Chanted vocalizations. Drummers gather in a circle around a newly fashioned frame drum held horizontally, a pinch of loose tobacco scattered across the drumhead. The drummers beat in unison. The collective sound of a common heart beat. Then it happens: resonance. The drumhead vibrates as it listens to the drumbeats that surround it. The tobacco strands dance on the stretched deerskin. A new drum is birthed. Ready now to sound. Ready now to sing.

“Drums have spirit. They are not just objects,” says Jean Becker, Inuit elder and Senior Advisor of Indigenous Initiatives at Wilfrid Laurier University. Her life journey stands as a testament to that conviction. A journey that starts, however, without a drum, without ceremony, without connection to her Indigenous roots. A journey that awakens, transforms, and inspires. A journey she invites others to take into the spiritual realm.

Born in remote and sparsely populated Nunatsiavut, Labrador, Jean is of Inuit and English ancestry. She has early memories of her family living on the land eating seal, caribou, fish, partridge, and geese. But while the diet may have been traditional, the ongoing destruction of her cultural heritage meant she rarely experienced expressions of Indigenous beliefs and rituals. There was no drumming in her childhood, no Aboriginal ceremony. Instead the Christian church dominated… or tried too. As a young girl, Jean rejected what she considered to be hypocrisy in the church, the disparity between the teachings and the actions of the adherents.

But nothing from her Inuit background remained to fill the void. She left home at 17. An atheist? An agnostic? She was unsure. Certainly without a spiritual centre.

Eventually, after many travels, she made her home in Southwestern Ontario where she encountered the Anishinaabe culture and the teachings of elders Art and Eva Solomon. Her welcoming experience was underscored by her recognition that her new teachers actually embodied what they taught. It was a refreshing difference. Art, who was at the forefront of the revival of Indigenous spiritual traditions, introduced her to a Midewiwin sacred ceremony. The impact was profound. Jean began to see herself differently. To see herself as someone who had value. She began to fully understand the fundamental idea: all beings are connected.

Jean also came to the realization she was someone who could make a difference. She joined Art in his work to bring Indigenous cultural practices into the prison system as a way to offer healing and transformation. Guiding her, on what would become her own transformational journey, were her newly learned traditional values, the Seven Grandfather Teachings: Respect, Truth, Bravery, Wisdom, Honesty, Humility, and Love. It was a challenging road. And through the trials of her own conflicts, failures, and emotional pain, she confronted a question Art often asked: “What does it mean to walk with Love?”

She found the answer in serving others. She had experienced the powerful effects of ceremonial gatherings, but while pursuing an academic career in Southwestern Ontario, Jean lived in an urban environment that offered few opportunities for connection among the Indigenous community. She set out to change the often solitary walk. In 2003, living and working in the Kitchener-Waterloo area, Jean organized a way for Indigenous urban women to meet, to socialize, and to find their voices: a drum circle.

Jean, however, did not own a drum, and she didn’t know any songs… yet. But the point was to form the circle; the drum and the songs would follow. With the help of Barbara Waterfall, a “Song Carrier”, Jean learned her first songs. In a drum-making workshop, she made her first frame drum. The ritual “birthing” of the drum revealed its distinctive voice and its purpose in calling both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women to form a community around the Seven Grandfather Teachings. Reaching into her Anishinaabe experience for a suitable name, she called the group Mino Ode Kwewak N’gamowak: The Good Hearted Women Singers. As participants shared songs from different Indigenous traditions, the circle grew into an opportunity to discover and express both individual and collective cultural identity. For many displaced women the drum circle became a safe place to share life experiences, a healing place to recover from emotional wounds, and a spiritual place to encounter the sacred dimension. According to Jean this progression was not so much her doing as it was a natural evolution that came from drumming and singing together: “The drum is the healer not the drummer.”

For thousands of years across diverse cultures, the drum has evoked the heartbeat of mother earth, the rhythmic power of the life force. In our mother’s womb, the first sound we experience is the heartbeat. No wonder drumming elicits a primal response. Drumming in unison summons our sense of shared connection with one another. It energizes both our bodies and minds. And for some, drumming carries them across a threshold into the spiritual realm. Such has become Jean’s passage.

Jean’s life-altering journey has opened the door for others to be changed as well. The spiritual animation of the drum circle comes out of careful and respectful preparation. The circle is opened with smudging, the burning of medicinal plants such as sage, sweetgrass, tobacco or cedar, as a ceremonial cleansing. The ancestors and their teachings are invoked as part of the welcoming ritual that includes the prayerful expression of intentions. No one person leads the songs. Rather, various individuals, taking turns, are encouraged to start the singing and are vocally supported by the group. Regardless of the musical talents of individuals, the attitude is the same: no one beats out of time; no one sings out of tune. The women follow a “sweetgrass teaching”. One blade of sweetgrass is not strong, but braided together the sweetgrass is resilient. Thus they support one another both in the drum circle and in their extended lives bound by a sense of community. After several rounds of singing, “The Travelling Song” bids a ritual farewell and acknowledges the connection to all things as represented through the physical movement of the drummers’ bodies turning full circle as they successively orient themselves to “The Four Directions.” The entire experience, with the frame drum at the heart, offers a portal to the sacred.

Thus Mino Ode Kwewak N’gamowak thrived. As did Jean, confirmed in her sense of purpose and direction. But illness can beat a jagged rhythm in our lives. Even in the life of a “Song Carrier”. Struggling with serious liver disease in 2007, Jean passed her role on to someone who had also been transformed by the power of the drum: Kelly Laurila. With Indigenous Sami background from Finland, Kelly had heard the call and had previously found her voice within the group. As Kelly and the Good Hearted Women offered support with healing songs and prayers, Jean turned to maintaining the very drumbeat of her heart.

Kelly continued the teachings and approach upon which Jean had founded the group. She also extended the group’s reach into the community. More and more the women were asked to perform at various social events. Not established as a performance group, they were stretched and challenged; but public presentations allowed them to carry their Indigenous voices beyond the immediate drum circle into a dynamic relationship with the wider community. Gradually Kelly increased the cadence. She actively sought ways for the group to interact with Settler People using music as a commonality. Events under the banner “Bridging Communities Through Song” hosted by Mino Ode Kwewak N’gamowak in partnership with other organizations, including the Police Choir, became forums for initiating dialogue and fostering understanding. Of course there were awkward moments and tensions, but the language of the drum resonated across cultures.

And Jean’s imperiled health? The jagged rhythm almost became no rhythm at all. As her illness progressed, only a transplant could save her. The wait was fraught with apprehension. The odds unfavourable. In the end, the woman who had devoted her life to serving others received the gift of life from a stranger. Another profound experience. Another rebirth. All beings are connected. The rhythm of renewal had prevailed.

After her remarkable recovery, Jean returned to her work as an educator at Wilfrid Laurier University. In the broader community she has responded to the call of being an elder: listening, encouraging, guiding and conducting traditional ceremonies. Throughout she has continued to ask, “What does it mean to walk with Love?” The narrative of her life-song and its ongoing legacy of service to others remains the answer. She has become what she admired in her first teachers: an embodiment of values taught. She has become The Woman of the Drum.

need them be just right. I want comfort, and I want to be surrounded by my things, photos of loved ones and art and quotes that inspire me, books and mementos. Of course, it would have been nice an entire room to myself—a room of one’s own—but since I have a family and a small apartment in an expensive city, I have to settle on a corner. In Toronto, I was lucky enough to

need them be just right. I want comfort, and I want to be surrounded by my things, photos of loved ones and art and quotes that inspire me, books and mementos. Of course, it would have been nice an entire room to myself—a room of one’s own—but since I have a family and a small apartment in an expensive city, I have to settle on a corner. In Toronto, I was lucky enough to  claim a corner of the living room that was separated by a book shelf, and since the living room was on a different floor than the rest of the house it felt fairly private. Last August we moved to Tel Aviv, and now I’m literally banished to a corner of the living room, writing in the middle of the house, while the kid and her friends run around and my partner is on the phone, or making dinner, or doing whatever. Some days, I try to wake up early to steal some quiet hours to write. I still love

claim a corner of the living room that was separated by a book shelf, and since the living room was on a different floor than the rest of the house it felt fairly private. Last August we moved to Tel Aviv, and now I’m literally banished to a corner of the living room, writing in the middle of the house, while the kid and her friends run around and my partner is on the phone, or making dinner, or doing whatever. Some days, I try to wake up early to steal some quiet hours to write. I still love  my little corner: my desk is facing a large window, which offers plenty of sunlight, breeze, and a nice view of the Tel Aviv skyline. I like having a window to the world and I like watching the street when I write. In the fall and spring, when the window is open, I can hear people talking from below, catch snippets of phone conversations. Sometimes, because I am writing in English in a Hebrew speaking country (in which my work is usually set) it can be disorienting. But I’ve long embraced this dislocation as a part of my life and my writing. The most luxurious item in my writing corner is my electric desk, which rises up by the press of a button, so I can alternate between standing and writing. Once spring rolls in and the rain ends, I plan to find an old desk and an office chair and drag them up to the roof of the building so I can sit there from time to time and write in peace. I’m ridiculously excited about this plan.

my little corner: my desk is facing a large window, which offers plenty of sunlight, breeze, and a nice view of the Tel Aviv skyline. I like having a window to the world and I like watching the street when I write. In the fall and spring, when the window is open, I can hear people talking from below, catch snippets of phone conversations. Sometimes, because I am writing in English in a Hebrew speaking country (in which my work is usually set) it can be disorienting. But I’ve long embraced this dislocation as a part of my life and my writing. The most luxurious item in my writing corner is my electric desk, which rises up by the press of a button, so I can alternate between standing and writing. Once spring rolls in and the rain ends, I plan to find an old desk and an office chair and drag them up to the roof of the building so I can sit there from time to time and write in peace. I’m ridiculously excited about this plan. (born in Saskatchewan, now resident in the UK) published Eve and the New Jerusalem, a well-received study of 19th-century feminism and socialism. Taylor seemed on the brink of a fine career. But overtaken by anxiety, she became addicted to alcohol and tranquillizers. As part of her treatment, she entered into a lengthy Freudian analysis, and at one stage was admitted to Friern Hospital, just at the time asylums were being closed in Britain and North America. This extraordinary memoir is Taylor’s account of her analysis, nestled within her consideration of the treatment of mental illness and a history of asylums. Taylor doesn’t spare her analyst, herself, or the reader in her harrowing narrative, but the writing is beautiful and her candour creates a story both moving and fully realized. (Spoiler alert: all’s well that … )

(born in Saskatchewan, now resident in the UK) published Eve and the New Jerusalem, a well-received study of 19th-century feminism and socialism. Taylor seemed on the brink of a fine career. But overtaken by anxiety, she became addicted to alcohol and tranquillizers. As part of her treatment, she entered into a lengthy Freudian analysis, and at one stage was admitted to Friern Hospital, just at the time asylums were being closed in Britain and North America. This extraordinary memoir is Taylor’s account of her analysis, nestled within her consideration of the treatment of mental illness and a history of asylums. Taylor doesn’t spare her analyst, herself, or the reader in her harrowing narrative, but the writing is beautiful and her candour creates a story both moving and fully realized. (Spoiler alert: all’s well that … ) I am currently rereading Adam Nicolson’s The Seabird’s Cry—rereading, actually, because on my first go-through I simply gulped it down for the double pleasures of his knowledge and his language. Now I’m making notes. In the author’s own words:

I am currently rereading Adam Nicolson’s The Seabird’s Cry—rereading, actually, because on my first go-through I simply gulped it down for the double pleasures of his knowledge and his language. Now I’m making notes. In the author’s own words: I didn’t pick up this Montreal classic until I’d already left the city. As soon as I opened it, though, I was instantly transported back to the neighbourhood of Saint-Henri, and back in time to WWII. The novel follows a working-class Québécois family as they fall in love, go to work, hang out in diners, sign up for the army, and try everything to make ends meet. It’s very sensitively written: the author takes us right into the minds of all the characters, especially Florentine, the adolescent daughter, as she nurtures a massive crush on someone who barely cares. Most of us have been there…

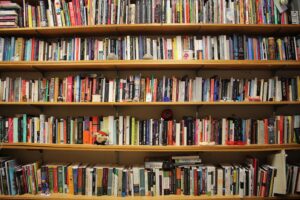

I didn’t pick up this Montreal classic until I’d already left the city. As soon as I opened it, though, I was instantly transported back to the neighbourhood of Saint-Henri, and back in time to WWII. The novel follows a working-class Québécois family as they fall in love, go to work, hang out in diners, sign up for the army, and try everything to make ends meet. It’s very sensitively written: the author takes us right into the minds of all the characters, especially Florentine, the adolescent daughter, as she nurtures a massive crush on someone who barely cares. Most of us have been there… My space is now painted a sunny yellow, has plenty of light, and is crammed with things I love to have close at hand. Bookshelves of course: poetry flanking both sides of the desk, fiction (authors A-Mc) along another wall, and a small shelf with various places where my work has been published (including THREE issues of TNQ!). Artwork, including the first original art I ever bought (a wintery water colour), illustrations from fairy tales and children’s books, two favourites among paintings by my late mother-in-law, a couple of pieces given to me as gifts, a line drawing entitled ‘Shy’ that people have said looks like me, and some palm-sized prints by Chris Tse and Manahil Bandukwala pinned to the end of one of the bookshelves.

My space is now painted a sunny yellow, has plenty of light, and is crammed with things I love to have close at hand. Bookshelves of course: poetry flanking both sides of the desk, fiction (authors A-Mc) along another wall, and a small shelf with various places where my work has been published (including THREE issues of TNQ!). Artwork, including the first original art I ever bought (a wintery water colour), illustrations from fairy tales and children’s books, two favourites among paintings by my late mother-in-law, a couple of pieces given to me as gifts, a line drawing entitled ‘Shy’ that people have said looks like me, and some palm-sized prints by Chris Tse and Manahil Bandukwala pinned to the end of one of the bookshelves. Lotsa tchotchkes (or mathoms as I prefer to think of them, after hobbits’ collections) grace the tops of the shelves, and most other surfaces. I have cloisonné and pottery that belonged to my mother, craft projects my children made for me, small gifts, and objects that I somehow acquired and that seem to belong. Spirals abound, in a carved stone fossil ammonite dish that holds two other ammonites, on a silver dish where I keep a spell-bottle my niece Nicole made for me, and on a ceramic bowl with a collection of buttons. Family photos, tote bags with meaningful logos, various assemblages of feathers/stones/shells/dried flowers…

Lotsa tchotchkes (or mathoms as I prefer to think of them, after hobbits’ collections) grace the tops of the shelves, and most other surfaces. I have cloisonné and pottery that belonged to my mother, craft projects my children made for me, small gifts, and objects that I somehow acquired and that seem to belong. Spirals abound, in a carved stone fossil ammonite dish that holds two other ammonites, on a silver dish where I keep a spell-bottle my niece Nicole made for me, and on a ceramic bowl with a collection of buttons. Family photos, tote bags with meaningful logos, various assemblages of feathers/stones/shells/dried flowers… I fight a constant battle with paper, trying to keep things more or less under control so that clutter doesn’t frazzle the edges of my concentration. I recently gave away, to a grad student acquaintance, an old desk from the basement. But getting rid of it meant that its jam-packed contents spent several months in boxes stacked around my writing room. Conquering the chaos by sorting and finding space for all that stuff in the closets and drawers in my room felt like a major accomplishment.

I fight a constant battle with paper, trying to keep things more or less under control so that clutter doesn’t frazzle the edges of my concentration. I recently gave away, to a grad student acquaintance, an old desk from the basement. But getting rid of it meant that its jam-packed contents spent several months in boxes stacked around my writing room. Conquering the chaos by sorting and finding space for all that stuff in the closets and drawers in my room felt like a major accomplishment. Of course, not all of my writing happens here. Most of my pen-and-notebook work is done in an armchair, either in the living room beside my ‘to be read’ stack of books and magazines, or in the room off the kitchen, which now houses the M-Z fiction bookshelves along with the TV. But the writing room is where I sit, at my insufficiently ergonomic desk, to do the real work of revising and fine-tuning my poetry and fiction, as well as writing pieces like this one. It’s also where I take care of the business part of writing – research (aka getting lost down internet rabbit holes), submitting to journals, such self-promotion as I feel comfortable with, staying remotely connected with writer friends, and spending almost certainly too much time on social media. I’m grateful for the privilege of this space, the touchstone objects I’ve filled it with, and the comfort and inspiration of the memories they evoke.

Of course, not all of my writing happens here. Most of my pen-and-notebook work is done in an armchair, either in the living room beside my ‘to be read’ stack of books and magazines, or in the room off the kitchen, which now houses the M-Z fiction bookshelves along with the TV. But the writing room is where I sit, at my insufficiently ergonomic desk, to do the real work of revising and fine-tuning my poetry and fiction, as well as writing pieces like this one. It’s also where I take care of the business part of writing – research (aka getting lost down internet rabbit holes), submitting to journals, such self-promotion as I feel comfortable with, staying remotely connected with writer friends, and spending almost certainly too much time on social media. I’m grateful for the privilege of this space, the touchstone objects I’ve filled it with, and the comfort and inspiration of the memories they evoke. My office is like our barn

My office is like our barn As a writer,

As a writer, My collage wall is

My collage wall is