What is Matthew Hollett Reading?

I first encountered the work of Irish writer and artist Sara Baume through a friend who recommended her novel A Line Made By Walking. The title immediately intrigued me – it’s plucked from an artwork by British artist Richard Long, who in 1967 walked back and forth across a field until his path was well-trod enough to became a visible line. I remember marveling over Long’s walk-work when I was studying conceptual art and photography in art school. Documented in a muted black and white photograph, the artist’s path stretches towards a cluster of trees and back, plain and shining. Nothing could be simpler, yet it felt like an invitation to ask questions about art that I had never considered before.

So I read Sara Baume’s curiously titled A Line Made By Walking, and I loved it. For me, Baume’s novel captures something of the post-MFA doldrums – after years of focused, intense work among fellow creatives and colleagues, being plunked into a world that doesn’t know or care about conceptual photography, psychogeography, or the Oulipo leaves you a little adrift and broken-hearted. In A Line Made By Walking, Frankie is a troubled artist who leaves Dublin in search of solace and space, moving into an ancient cottage once inhabited by her late grandmother. She walks, sulks, and photographs small dead animals, attempting to pull herself together as the house falls apart around her. It’s a novel about depression and grief, about looking closely at things that make you uncomfortable, and about seeking comfort in a dispassionate world. It’s also rooted in place in a way that I really love. Baume’s prose is restless and evocative, with the concise inquisitiveness of the best poetry.

Though she’s published four books, in interviews Sara Baume calls herself an artist first. Much of her writing is semiautobiographical. Her tiny painted plaster sculptures of birds are scattered throughout Handiwork, a 2020 nonfiction project that perhaps comes closest to synthesizing her art and writing practices. “I have always felt caught between two languages, though I can only speak in one. The one I can speak goes down on paper and into my laptop, in the hours before noon. The one I cannot speak goes down in small painted objects, in the hours after.”

Handiwork is a book you can dart, birdlike, in and out of. It’s not quite a journal, but an interwoven series of memories, musings, and impressions. Baume writes about the soundscape of her studio, the poetics of migrating birds, the paint under her fingernails, and her relationship with her late father, “a scratch-builder of the monumental” who built everything by hand. His memory lends the book a certain melancholy, though Baume’s observations are mostly buoyant, wry and lyrical. “I would like to know at what stage of life a person stops making small, painted objects, and how I managed to overshoot it.” As an artist-turned-writer myself, Handiwork’s everyday reckonings hit home. It’s rare to come across a book that captures not only the artmaking process, but the artmaking instinct – along with the second-guessing, callouses, and occasional moments of magic that accompany that way of being.

Matthew Hollett is a writer and photographer in St. John’s, Newfoundland (Ktaqmkuk). His work explores landscape and memory through photography, writing and walking. Optic Nerve, a collection of poems about photography and visual perception, has just been published by Brick Books. Album Rock (2018) is a work of creative nonfiction and poetry investigating a curious photograph taken in Newfoundland in the 1850s. Matthew won the 2020 CBC Poetry Prize, and has previously been awarded the NLCU Fresh Fish Award for Emerging Writers, The Fiddlehead’s Ralph Gustafson Prize for Best Poem, and VANL-CARFAC’s Critical Eye Award for art writing.

Photo by Dariusz Sankowski on Unsplash

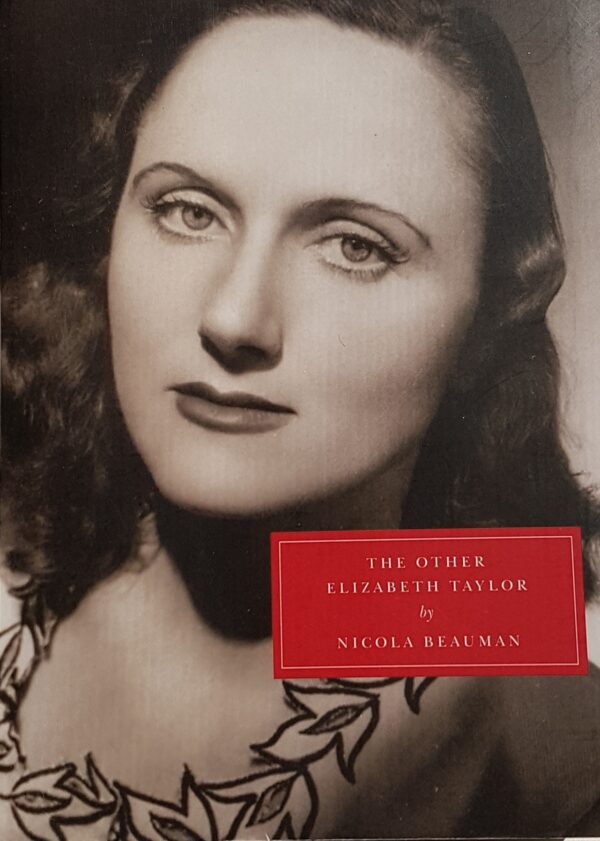

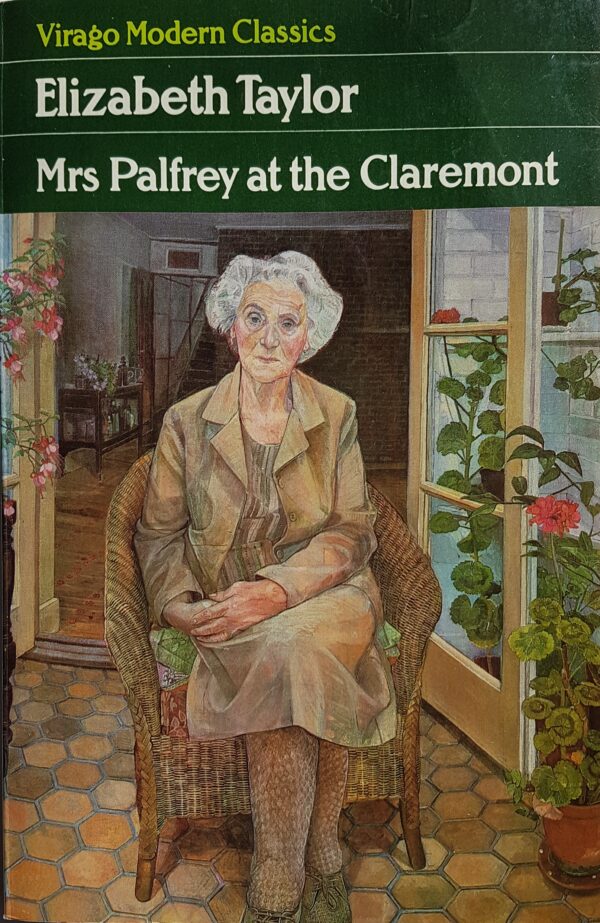

This Elizabeth Taylor (1912-1975) was an English writer who published 12 novels and also wrote short stories, many of which appeared in the New Yorker. She was championed by friends like Kingsley Amis, Ivy Compton-Burnett and Elizabeth Bowen. And she needed champions because she was often panned by the critics, dismissed as a boring, suburban wife and mother with nothing to say for herself. Condescended to because she wrote about domestic

This Elizabeth Taylor (1912-1975) was an English writer who published 12 novels and also wrote short stories, many of which appeared in the New Yorker. She was championed by friends like Kingsley Amis, Ivy Compton-Burnett and Elizabeth Bowen. And she needed champions because she was often panned by the critics, dismissed as a boring, suburban wife and mother with nothing to say for herself. Condescended to because she wrote about domestic