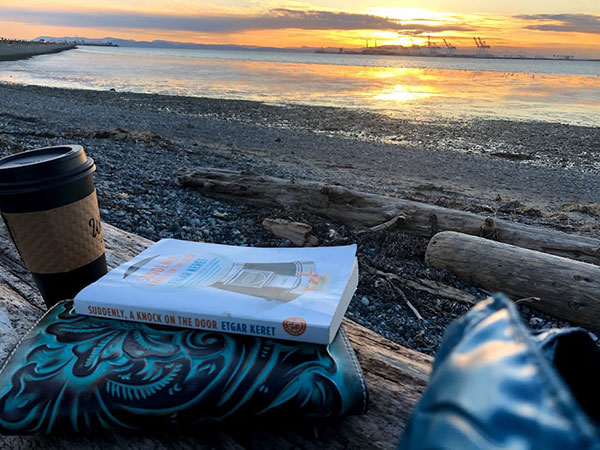

David disappeared in December of 2005. We thought he had walked into the Yukon River but didn’t know for sure. I went up to Whitehorse in June 2006, after the ice had come off the river. His body was found the day I arrived, an eerie coincidence. The time spent there—talking to friends, former employers, ex-bandmates, going to the bars he used to play in—was the most valuable research. I could try to inhabit his life up there, to see what he might have seen. In a way the book draws a line between what appeared to be an idyllic childhood and that final moment standing at the edge of the river.

With the larger issue of suicide research, there is the problem of reliable data. Suicides are under-reported (by some estimates, by 60%) and suicide isn’t a government priority in Canada. The data is getting more comprehensive, but there’s still an element of conjecture. Suicide isn’t always logical, and the data and stories and research often reflect that.

Q: Why did you decide to expand the scope of the book to include the broader research on suicide?

After my brother took his life, three old friends (and recently a fourth) took their lives. They were all middle-aged men. It seemed to be a disturbing trend and when I started researching, I found this was, in fact, the case; middle-aged males now had some of the highest suicide rates. I thought that by opening up the story I might gain more insights into my brother’s decision. I think it helped, certainly. With suicide there are so many roads you can go down—teen suicide, military suicides, cluster suicides. I decided to limit my research to middle-aged baby boomers, and centred on men, whose rates are four times that of women (though women make more attempts). It is the world I’m most familiar with—the problems and experiences are ones I know and understand at a visceral level.

Q: What surprised you in conducting research, or in the writing process, for To the River? What did you learn along the way that perhaps wasn’t part of your initial plan or the questions driving the book?

I interviewed a sociologist from Rutgers University who had been studying suicide. One surprising thing she told me was that baby boomers have always had high rates of suicide. When we were in our twenties, our rates were triple those of our parents. In middle age, the rates went up. There is an expectation that when we become genuinely old, when no amount of yoga or Botox or Rolling Stones concerts can convince us otherwise, the rate will go up yet again. Our suicide rates are higher than previous generations but also higher than the generations that have come after us. The Rutgers sociologist said boomers may carry a unique risk for suicide. A surprising and disturbing thought.

Q: With such a personal story, how do you let the book have its own life in the world after publication and balance that with protecting yourself and your family?

When I first wrote an autobiographical piece for a magazine years ago, I was mortified when it appeared in print. I felt so exposed. That feeling tends to disappear, I think, for most writers. This is the story we are compelled to write. Joan Didion wrote a piece where the first paragraph announced that she and her husband had gone to Hawaii instead of divorcing. An intimate disclosure, but she said the writer works with what they have.

Q: The way you frame the events on the Yukon River with your childhood on the Red River lets the reader feel not only the danger of rivers, but the wonders. In fast-moving scenes, you render the childhood you shared with your brother vividly—the tree forts and fights and adventures, your emerging talents, your different personalities. How are you able to go back in time and recreate all that detail? Were you that kid always carrying a journal?

I wish I had kept a journal. It’s something that appears on every New Year’s resolution list. The only exception is I keep a very detailed journal when I travel, which made the Yukon section possible. As for childhood memories, I find that once I start writing, it’s surprising what comes back, and how detailed those memories are. This isn’t to say they are entirely accurate. I have a vivid memory of my brother showing me the tattoo on his chest. We are in his bedroom, and he’s pointing to the osprey he had on his chest (Osprey was the name of his first band). Except, as several people pointed out, it wasn’t an osprey. It was the old RCA Victor logo of a dog listening to a Victrola record player. So, there are pitfalls as far as memory goes.

Q: Writing non-fiction, are there ways to check your subjectivity when relating events that you are involved in? How do you let readers know where the attitudinal fault lines are, for example, in reporting difficult relationships like the one with your sister-in-law? Or is this simply the territory of memoir, and there’s nothing to be done?

We may strive for objectivity, but it is largely a myth, I think. But we can be aware of the nature of our own subjectivity and biases and hopefully adjust accordingly. It is difficult to write about difficult relationships. There are places where I employ the fictional technique of “show don’t tell.” So, the reader sees that person doing something unfortunate, something that illustrates their character, or lack thereof, rather than me saying she is awful (though there is a bit of both in the book). But this is still a form of subjectivity; the writer picks the scene. In her book, The Journalist and the Murderer, Janet Malcolm writes that in journalism, the subject always thinks the story is about them, but it’s not, it’s about the journalist.

Q: Do you tend to write full drafts before editing? Rewrite a lot? I’m curious about the chapter entitled “Solo Canoe”, which is a moving, atmospheric scene, pivotal to the story.

I edit as I go and tend to do a lot of re-writing. The farther into the book I get, the more re-writing. I also tend to write longer and cut out quite a bit. I cut more than 10,000 words from To the River. Generally, these were tangents that explored other aspects of suicide. In the end, I realized that these detracted rather than added to the book, and I cut them out.

With a chapter like “Solo Canoe,” where I’m in real time but going back to childhood canoe trips and other memories, I wrote longer but cut it down to what I felt was its essence. You don’t always know what book you want to write when you set out. Sometimes I think I know, but that shifts once I’m immersed in it.

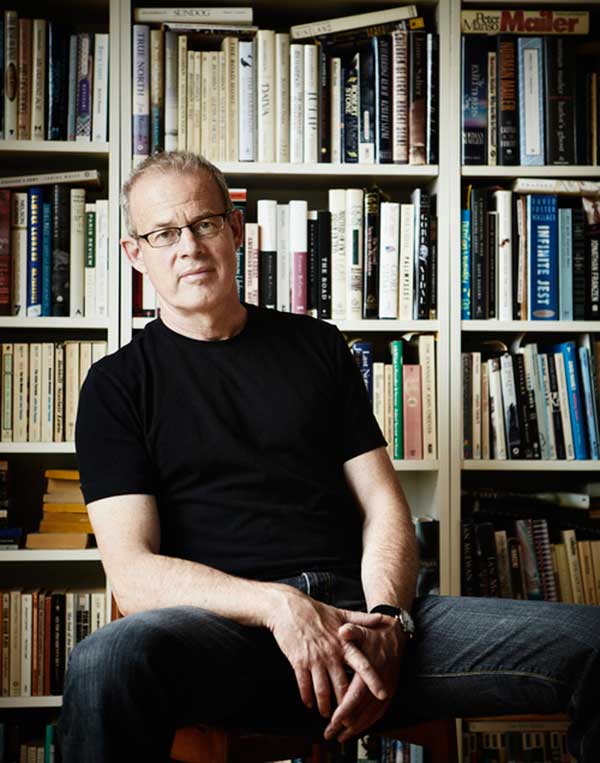

Q: Which writers do you turn to for inspiration? Who do you read, again and again?

For non-fiction, my go-to writers include James Salter (Burning the Days). He writes so beautifully, and with a curious economy. You get a sense of things—people, a place, a particular time—with only a few gorgeous paragraphs. I have gone back to Joan Didion’s The White Album more than once. Few writers can create a mood as well as she can, and that mood can be more resonant than detailed description.

Q: Suicide is, for many, still a taboo subject. We are often at a loss in talking about grief of any kind, and this kind seems especially painful. To what extent did the idea that the book could open up or normalize those conversations play a part in your thinking? What reactions to the book have you noticed, so far?

I did hope that To the River would contribute to the conversation that seems to have started in the last several years. While we still don’t have a real understanding of suicide, at least those conversations are taking place now. There is usually a nagging fear after any book hits the market about how it’s going to be received. The reaction to the book so far has often been one of gratitude; people writing to say they’d experienced something similar and it was good to see that story in print.