Month: January 2021

Finding the Form with Alice Zorn

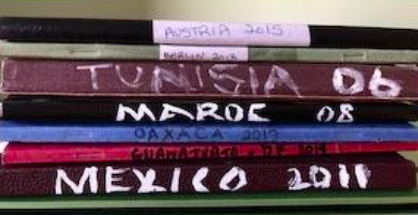

Place speaks to me, and when I travel, I keep detailed notebooks in the hope that I’ll one day get an idea for a story in that setting.

I wrote this story, “The Land of Clouds”, in 2018, a year after I returned from Oaxaca in Mexico.

I didn’t know about weaving with feathers before I saw the pieces in the museum there. I always go to textile exhibits. I have a passion for how people use fibre.

I had already begun to do research into historical textiles with a view to writing a new novel, and had asked the McCord Museum in Montreal if I could visit their conservation laboratories. That was in 2015. I wrote pages and pages about textile conservation, before realizing that the novel was moving in another direction and those pages didn’t belong. I had to cut them.

I knew that if I wrote about Oaxaca, I wanted to include feather weaving, but how to do that so it would be compelling? From the deeply committed point of view of the artist talking about her art.

I was still itching to write about textile conservation. I’m interested, too, in how people can become friends around the work they do.

Once I have characters, a setting and details for a story, I plan a loose narrative. So loose that I don’t yet know how I’ll proceed, only where I want to end. I usually have an idea of the ending I’m writing toward. The wording will change but not the final scene.

I like collage structures and for this story wanted to move between Montreal and Oaxaca, past and present. For the first few drafts, the narrator was in third person, but that felt too stiff. I rewrote the story in first, which didn’t change who she was but I felt brought her closer to the reader.

Alice Zorn is at work on a new collection of short fiction. Her novel, featuring a woman with Down Syndrome, is looking for a home. She lives in Montreal.

Photos graciously provided by Alice Zorn.

Cover photo by Paco Vaca.

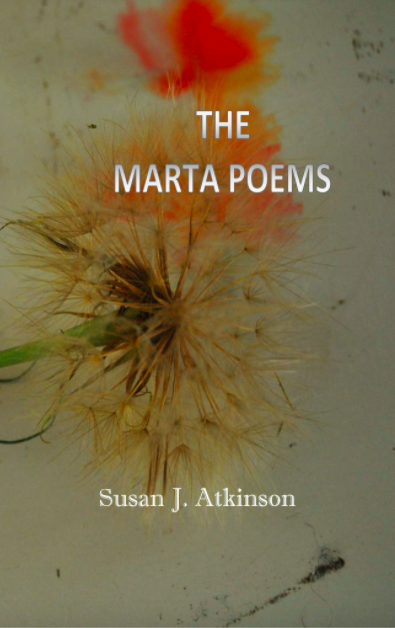

An Interview with Susan J. Atkinson

Like many poets, Susan J. Atkinson had been writing for a long time before the launch of her first book, The Marta Poems, in December of 2020. The New Quarterly poetry editors are not alone in their admiration for the work of this Ottawa-based poet. This interview touches on the book’s publication, subject matter, and poetic craft.

John Vardon: We are often told that there is too much poetry being published in Canada due to generous provincial and federal grants. But it seems to me that it’s still not easy to get a book published, even if it has garnered awards and editorial accolades, as your poems did. Can you say something about how you came to publish The Marta Poems with Silver Bow Press, which is located in British Columbia. Did they find you, or did they you find them.

Susan J. Atkinson: That’s a great question. Just to state the obvious, I don’t think there can ever be too much poetry published! I do agree that there are many opportunities, including wonderful grant opportunities, for Canadian writers. That being said, there is an incredible amount of competition for publications. We seem to be a nation of fantastic poets.

During my first round of submissions, I sent the collection to six publishers. Two never replied, one was a form-letter rejection, and three offered super positive and some helpful criticism. Each publisher had seen samples and then asked for the full manuscript—always good for raising hope but all three passed, citing a similar tale that the work was strong and well-written but they had too many returning poets on their roster that year and didn’t have enough room for it. Must admit I was quite defeated and sat on the manuscript for almost a year before sending it out again.

Once my bruised ego healed, I made some revisions, some based on the helpful comments from publishers and with a boost from my supportive mentor, Rhonda Douglas, who assured me the poems would find a home—the right home, I researched other publishers and found Silver Bow Publishing in New Westminster B.C.

Within weeks, Candice James, the publisher at Silver Bow, offered to publish the poems, and it was the beginning of what I can only describe as a fantastic relationship. Candice has been tirelessly patient, attentive, supportive, everything you could ever dream your publisher to be. She always makes me feel like a top priority and is open to all my crazy ideas, including using one of my photographs for the book cover.

I couldn’t be happier with the process, the final product, the entire journey!

JV: It’s one thing to write about people who are long or not so long dead, whether the purpose be elegiac or a kind of re-visioning poetic biography; it’s another thing to write about people who are still alive and could read your poems, especially if one of these people is a neighbour as your subject was. Did this fact constrain you in any way, a question I ask knowing that you have also written poems about at least one of your daughters.

SJA: Honestly, the lion share of the collection was completed after Marta passed away in 2012. While she was alive, we forged a very unlikely friendship, though I suspect it was borne through the age-old opposites-attract theory. Over the course of the 12 years of knowing Marta, we spent many hours sitting, either on her front porch or in her living room, just chatting. She would tell me stories and, as time passed and the stories churned in my head and began to evolve into poems, I began to ask questions, probing into how she felt or could she elaborate, all of which was my need to fill in all the missing pieces.

Marta knew I was collecting her ramblings and rewriting them as poems. She also knew I was sending them to publishers and that I was planning on compiling a book. She never asked to read them even after the first two poems, “Marta’s Shadow” and Marta On Sleeping,” (the original title) were published in Room Magazine in 2008. She was interested.

There were many, many gaps in Marta’s story that became gaping holes when I was trying to sew her life together. The section in Rhodesia is the best example. The only information Marta had shared was that she travelled from Siberia to Rhodesia and that her living conditions were slightly more palatable than those of some of her fellow refugees because of her skills as a seamstress. I often wonder what she would have thought of the love affair I bestowed on her. I think she would have loved it!

JV: I was emotionally engaged by the narrative element of these poems but also intrigued by the precise language and the various poetic forms used to convey Marta’s experiences. What decisions did you make about telling the story in a variety of ways.

SJA: I was very conscious that above and beyond, and foremost, I was writing a book of poetry and though many of the poems err on the narrative side, I hoped/I hope the book will be seen as a collection of poems that tell a story rather than a story written in poetic verse. In my mind, the distinction being that many of the poems can stand alone outside the collection.

I looked at each poem as its own entity, top of mind being what form would suit the particular moment or theme of each piece. I chose couplets for the poems that hold an intensity between two characters, italics for the diary entries (these are the narratives that written in the first person, intended to give Marta a voice in her own story), giving these entries a distinct look in the book. Other poems I just love the way they look on the page! I like a lot of white space between stanzas and couplets but, if I had used the usual amount of space that I like, the collection would have been 210 pages rather than 110.

JV: There are times in the book when it seems as if one is reading chapters from a novel or watching scenes from a movie—not simply because of the storyline but also the repeated visual and auditory motifs, much like those in a musical film score. How did your experience with photography and film making influence your poetic project.

SJA: That is an interesting observation, connecting my background in film to my poetry. It’s one I hadn’t ever thought about but now that you mention it, I can see what you mean. I also suspect that you are right and that both photography and film have inadvertently spilled into my poetry. I wonder if it’s because my first inclination is to play everything through my mind like a film reel.

The best way for me to feel a poem is to see it. Putting myself into the moment and being able to act or walk through the scene helps to round out and add the much-needed layers and depth, whether they be descriptive and concrete or more abstract and emotion-based.

I have to add that I love this question because it really made me think, where do the seeds or beginnings of my poems come from? I suspect you’re right. Nine times out of ten, it’s visual—I see the moment, the scene, and then build around it.

JV: In TNQ’s “Writing Spaces” feature, you recently mentioned that your study is “crammed” with poetry books and other “bits and bobs.” What poetry books hold a prominent position on your shelves. This is a roundabout way of asking the tired question about poetic influences.

SJA: My first love in poetry was the great World War 1 poet, Wilfred Owen. I loved, still love, his ability to capture a scene and fill it with sound and images. I love his way with language, which is often plain. That doesn’t seem to be much of a compliment, but what I mean is how he uses everyday language that clicks together with rhythm, emotion, and depth.

Another early influence was William Carlos Williams. Again, I love his skill at creating brevity that drips with emotion and underpinning layers. In fact, I love his work so much that I fashioned one of the Rhodesia poems in his footsteps. “Afternoon Portrait’ derives its form from Williams’ poem by the same name.

There are many fabulous contemporary poets—many of my favourites are Canadian, among them Deanna Young, Sandra Ridley, Rhonda Douglas, and Sue Goyette. Writing this out, I see a pattern—the ability of these writers to use the everyday, the ordinary and then, through their language and keen eye, they transform it into beauty and the extraordinary.

JV: It’s perhaps early to ask about the next collection that you may be envisioning, given that you have so recently launched this one, but do you see a new collection setting sail at some point?

SJA: Funny you should ask! I am in the process of the final edits on my first chapbook, The Birthday Party, The Mariachi Player, and The Tourist. The chapbook will be coming out soon through Catkin Press. It comprises 17 poems, each written in seven couplets, chronicling the events of a single night that begins with a birthday party. There is a nice thread connecting each poem that includes a similar refrain and a Mariachi song.

I am going to turn my attention to a second chapbook, the small book of loss, which surprisingly does not tell a story! I’m thinking 2021 may be the year of the chapbook for me.

Cover photo by kim mastromartino on Unsplash

Read more

Thursday’s Child: The Marta Poems by Susan J. Atkinson

As a poetry editor for The New Quarterly, I first encountered Susan J. Atkinson’s work when reviewing forty applications for an Ontario Arts Council grant about two years ago. Among the poems carefully excerpted from in-progress manuscripts by writers both emerging and well established, her selection stood out—a unanimous choice by our four-person poetry editorial group. Her progress description made it clear that she had been working on the poems for some time; the finished product makes it seem as if she has been doing so for most of her adult life. The book is—forgive me for lapsing into blurb-speak—a compelling and assured work, unified not only by its credibly depicted poetic protagonist but also by a variety of motifs—recurring and sometimes sadly ironic images, allusions and actions. The overall effect is novelistic or, even more aptly, cinematic (perhaps it is not surprising that the author was involved film production for over a decade).

Marta is a displaced person, a DP, an acronym which, as my mother gravely informed me decades ago, was often used derogatively in Canada to refer to thousands of refugees relocated to various countries after their forced uprooting, imprisonment and enslavement during WWII. Marta is multiply displaced, and the book follows her relocation from Poland via cattle car to Siberia and then after a year of involuntary labour, the journey to Rhodesia, England and, finally Canada, only the last of these relocations being a matter of choice.

Allusions to nursery rhymes and fairy tales—Snow White, Rapunzel, Hansel and Gretel—abound in the poems about Marta’s childhood in Poland, and her life as a young girl does contain traditional storybook elements. Her mother dies in childbirth, and she is raised by a stepmother who, if not notoriously wicked, cares so little for Marta that she ships her off to relatives in the country much too shortly after the death of her father from an illness contracted as a coal miner. A double irony is at work in his earlier reference to his daughter as Thursday’s child, for she has very far to go but her subsequent life symbolically suggests a more appropriate birth as Wednesday’s child, whose life is full of woe. Despite the comfort and kindness she experiences in her “little cottage in the woods,” Marta is still saddened by her father’s death and undeservedly burdened by guilt over her mother’s. Living “with a family that treat her/like a princess, Marta is wary of apples/especially the red ones.” These allusions are far less frequent in the rest of the book as fairy tale unpleasantness gives way to an evil that is anything but make believe, only to resurface near the end of the book (and also close to her death) in “On Sleeping,” when Marta dreams about a sinister dark-cloaked figure selling apples from a cart: ”Marta wants one. She wants a bite, a bite for her child/a magic bite to stir the girl who held her breath until/ the man in the white overcoat said she was dead.”

“The book is—forgive me for lapsing into blurb-speak—a compelling and assured work, unified not only by its credibly depicted poetic protagonist but also by a variety of motifs—recurring and sometimes sadly ironic images, allusions and actions.”

But any happiness in Marta’s life is, to use Alice Munro’s words, “like a bubble that’s about to break.” The coming darkness is foreshadowed in the last poem of the first section, ,”Her Name—June 1940,” in which she innocently “practices writing her name/plays at adding an h.” This scene is reminiscent of another more famous fictional orphan, Anne of Green Gables, who famously explains the greater distinction afforded by the final e. Of course, the added letter here takes on a much more sinister significance in the final phrase, “in case it is needed.

The “little cottage in the woods’ burns down and, shortly thereafter, she and her loving step-parents are shipped to Siberia by truck and train, “cooped with others/in cattle cars.” “Trapped in closeness, others kneecaps like sharp sticks/poking her thighs,” Marta endures weeks of starvation and thirst, finally arriving at a farm in Siberia, where she is immediately put to work pulling thistles in a wheat field, her hands “blistered and bleeding, prickles digging under her skin.” Surviving a year on minimal food and water, suffering from dysentery and pneumonia, Marta is fortunate to be among a group of Poles sent to Abercorn Camp in Rhodesia. Amid the relative comfort and security, Marta experiences what may be the only true love of her life, “a man with sweet cinnamon skin,” becoming for the first time “both a lover and a beloved.” Racial, social, and political realities make a more permanent relationship impossible, and Marta must abandon her lover and travel to England, where she meets and marries, more out of sympathy and convenience, a soldier still traumatized by the recently ended war. Expecting their first child, Marta and John enjoy a brief period of contentment during her pregnancy and birth of their only child, Irena. This section contains two of the most wonderful poems, one blissfully happy, the other unbearably sad. In “Her Sunlight,” Marta

watches Irena plant her foot in a pool of sunshine

shadow of her tiny body fluttering through warmth

like a butterfly ready to land

the child is mesmerized by the falling petals of light

bends to smell them, touch them, pick them

.…she crawls along the floor

sinks so close to the ground, face pressed body curled

around the buttery yellow splashes,

a comma at the end

of an unfinished poem,

But such moments prove ephemeral, as we might have expected by the irony suggested by the name “Irena,” derived from the Greek word meaning “peace,”a state destined for only a few brief stays in Marta’s life. In “Lullaby,” we learn of her daughter’s quiet, heart-breaking death. Holding the child in her arms,

Marta puts her cheek to her daughter’s nose feels

For the slip of warm breath from her mouth

But there is nothing. The room is still is so still Marta catches

her own breath to stop the pounding of her heart.

Marta’s desolation is vividly imagined in “Changing the Clocks,” where she refuses to set back her clocks and “make one more hour of darkness/instead she lives in limbo.” In “Stains Have Memories,” Marta comes to regret her earlier efforts to clean her daughter’s room “so many times/it can’t be possible/for a stain to remain/ to remember all the things/she wishes it could”—but eventually finds that she can’t “forgive herself for/ scrubbing away/ the stain/the feel/the smell.”

Atkinson never deals directly with Marta’s death. Instead, she offers a final poignant poem in her own voice, “After Life,” in which she finds herself standing on the curb watching the rain destroy the leftovers of Marta’s now emptied house: boxes of letters, photographs, and other papers now turning slowly to mush on the curb before the garbage truck carries it to landfill oblivion. Whoever cleaned out her house “didn’t care about the weather/ or what was in those boxes reeking of age and sickness,” “cardboard coffins I had always wanted to glimpse,” now guzzling the October rain.” The poet retrieves what she can, carrying “envelope on envelope” to her basement… a thousand drowned moths sopping wet and tissue-thin/aching to survive.”

“What also speaks to the poet’s craft are the many poetic forms and figures of speech used throughout the book—effectively alliterative and assonant phases, italicized testimony in Marta’s voice, ghazal-like couplets, poem suites, and anaphora.”

Much to her credit, Atkinson manages to balance the strong sentiment generated by her poems with a high degree of poetic craft. Apart from the fairy-tale motifs mentioned earlier, she uses a host of repeated images, a notable example being on handkerchiefs and napkins, some folded for the delight of children, others fashioned from Marta’s rapidly shortening slip to make money on her way to Siberia, or still others compressed into ever smaller tear-soaked squares and hidden in a drawer as a way to end her constant weeping..

Bread or bread crumbs take on more than a fairy tale significance in many poems, in incidents like the moldy bread thrown on the floor of the cattle car, fallen upon by the occupants “like hens pecking at corn” ; the feeding of ducks in a London park (a clearly ironic parallel); and, toward the end of the collection, in a poem titled “Resolutions,” another of Marta’s responses to Irena’s death, when she sits at the breakfast table and

sculpts crumbs into the scarred wood

By 10, a little girl moulded

From the bread smiles at her,

Small heart beating

The most prominently repeated activity in the book is Marta’s sewing, which becomes a metaphor for her endurance and survival. Learning the skill as a child, she sews in guilt over her mother’s death; she sews to make money in Siberia, Rhodesia, and Canada; she makes dresses out of only the darkest material in which “to wrap her sadness”; she fashions a quilt incorporating long-kept scraps of paper and cloth, eventually wrapping it up and hiding it under the bed as a way of coming to terms with the memories these scraps evoke.

What also speaks to the poet’s craft are the many poetic forms and figures of speech used throughout the book—effectively alliterative and assonant phases, italicized testimony in Marta’s voice, ghazal-like couplets, poem suites, and anaphora, the latter used in “All the Small Arguments,” where the repeated phrase “she kept them” introduces items in a list of marital grievances and repressions which Marta metaphorically seals up “in a small brown leather satchel/that had a broken clasp.” There is even what I take to be a concrete poem, “The Quiet Years,” which describes her quilt- making efforts somewhere toward the end of her life—a poem arranged on the page to resemble the patches gathered together in a bedspread.

In an on-line video from a reading given at Ottawa’s ling-standing Tree Reading Series (2017?), Atkinson mentions writing a collection based on “a little old lady who lived on her street” and explains that she wants to tell us a little “ about the small and the ordinary.” On the basis of these poems, I’d say that there is nothing small or ordinary about Marta or the poems themselves.

Photos courtesy of Susan J. Atkinson.

Read more

Poem in a Pocket Leads to Singing in a Parkade

For the last number of years during April’s “Poem in Your Pocket Day”, I have shared a poem with colleagues, family, and friends by email, often prompting exchanges celebrating the value of poetry in our lives and sometimes raising the question of a poem’s potential to change us. But this year… this tough, tough year… it was my email signature lines that underwent an unexpected transformation — into song.

“if only for one ruby-throated moment

you could drink

from the chalice of the sun”

Composer Leonard Enns inquired if that “stimulating snippet” at the end of my email was part of a longer poem. Should the text and his musical concepts align, he would consider setting the poem as a choral piece. I was thrilled. The poem, exploring the idea of living with intention, and living “at the pitch”, had been written almost 30 years ago and gifted to my wife. One of my favourites, it had been published in TNQ in 2007. What new voice might Leonard give the poem?

Leonard, in fact, had challenged himself during the pandemic to compose a series of short choral works, having no idea when or if they would be performed. One of his driving motivations was the experience of having a friend in an ICU for a month with COVID-19. On a ventilator, in an induced coma, the friend survived; and Leonard imagined one day they could again “drink from the chalice of the sun”.

As the new compositions took shape, Leonard rehearsed them with members of DaCapo Chamber Choir, outside and distanced to suit the new restrictions. They even tried an historic jail exercise yard, but the sound quickly dissipated with no roof to contain it. Then an imaginative solution: a parking garage as a concrete cathedral. No walls but a hard ceiling. Ventilation and resonance both. Juxtaposition of utilitarian architecture and exquisite sound.

With technical recording expertise by Chestnut Hall Music and the City of Waterloo providing the venue, the “garage choir” has emerged to affirm the creative human spirit. And Leonard, as Director of DaCapo, in his New Year’s message spoke to how the lines of the poem express

“… the wonder, grace and joy which we wish for all of our listeners and choral friends as we embark on 2021. We have been restrained and constrained in many ways and will continue to be so, but our capacity to see the world with fresh eyes, to embrace life with joyful acceptance, need not be limited.”

From snippet to score. From pocket to parkade. A poem’s journey into song.

One Ruby-throated Moment

by Rae Crossman

if only for one

ruby-throated moment

your life could hover

rapid

radiant

rare

you would never let the quiver

out of your bloodstream

seek always the nectar

you sensed was there

if only for one

ruby-throated moment

your heart could beat

a hundred thrilling times

a hundred exclamations

a hundred revelations

a hundred prayers

if only for one

ruby-throated moment

you could drink

from the chalice of the sun

Rae Crossman writes poetry both for the page and for oral performance. He has published poems in literary magazines and dramatized them on theatre stages, in classrooms, and around campfires on canoe trips. Collaborative projects include storytelling with dance, text for musical compositions and recordings, and theatrical pieces set in natural environments. Living in Kitchener, Ontario, he is the recipient of a Kitchener-Waterloo Arts Award for his work across artistic disciplines.

Photo courtesy of Rae Crossman. Cover photo by Ivana Cajina.

Read more

Wild Writers Mentorship Program Reflection

As a writer, I crave feedback. To have someone read the lines that have long since engrained themselves in my mind, and strip away the excess.

As a developing writer, I also long for mentorship. I want to know that I’m not writing alone.

The Wild Writers Mentorship offers the opportunity to receive both of these things through a personal session with an awarded author or editor. I met with my mentor over Zoom and across time zones.

The session was engaging and encouraging. I left feeling seen, understood, and equipped with actionable steps for growth in my manuscript and in my writing life.

My mentor first reached out to me in early December, and we discussed my personal essay over Zoom a few weeks later. They addressed my piece as a whole and offered feedback on story, structure, flow, and formatting to make it more cohesive. They worked with me to identify the questions at the core of my piece and to refine my central focus.

Not only did I receive encompassing feedback, but my mentor also provided me with close edits, down to word choice and sentence structure, to ensure I was conveying what I was actually trying to say. I appreciated receiving verbal feedback, because I could ask questions and discuss specific recommendations as they were offered.

My mentor also made space for my questions relating to industry and the creative process. They asked about my goals and offered book recommendations based on my interests and lyric creative nonfiction style.

This year, the mentorship process finished near the end of December, so I launched into a new year with fresh revisions to make, books to read, projects to complete, and ideas to explore.

Thank you to the Wild Writers Mentorship team – Susan, Helen, Andrew, and Pamela – for creating a program tailored to fill a need, and for providing leadership in such a gracious way. I am most grateful.

Reba Kingston is is currently writing from unceded Lekwungen territories in Victoria, BC. She is a writer and active travel guide, leading cycling and hiking trips in the Canadian Rockies and across Europe when global circumstances allow. Her writing has been shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s Constance Rooke CNF Prize

Cover photo by Fernando @cferdo.

Read more

What is Mia Anderson Reading?

What am I reading? The internet. That’s because I am translating a very fat tome and must be looking things up constantly and being constantly grateful for the trustworthy scholars who have uploaded texts on the 17th century designation or connotation of this or that title or function or dwelling or boundary. More of that anon.

You could say I’m reading cable news too, couldn’t you? That’s partly because so much implacable evil is going on—hare-in-headlights frozen-terror stuff—and partly because I cook a lot because I grow a lot of things and freeze them because I have a lot of freezers because I used to sell lamb because I used to be a shepherd because. Listening to cable news while you prep the Brussels sprouts is like the latest audiobook. Must count as one, no? The words go in and in and in—and the lists come out and out: lists I’ve started in notebooks to keep track of the debasement of the language. Could become a book. Which you could read.

Have you noticed the word ‘shone’ no longer exists in the U.S.? It’s all ‘shined’. ‘Borne’ has become ‘beared’. It hasn’t ‘beared up under the stress’. And don’t tell the dog to get off the sofa; tell him to ‘get off of it’. And ‘different than’ is winning. Has won. ‘Different from’ is now quaint. I admit the ‘than’ is efficient, but. And I like growth in language, as in the garden. Like ‘grift’. We had thought ‘graft’ good enough, but this is tabasco sauce to the mix. And we really need the (fairly) new portmanteau ‘infodemic’. Though I’d like to upgrade it to ‘misinfodemic’. My reading ears will tell you it’s needed.

Even growths upon language can be good, but not all barnacles are edible. Do we really need the double ‘is’? ‘The thing is is that’. Now topped (we’ve lost the word ‘trumped’ for a while longer yet) by ‘The reality is is…’. And then we get into redundancies. My little booklets are piling up, like others’ unread books.

“Even growths upon language can be good, but not all barnacles are edible.”

Among my most beloved unread books are Wisdom in the Body: The Craniosacral Approach to Essential Health, as well as Foundations in Craniosacral Biodynamics Vol II: The Sentient Embryo, Tissue Intelligence, and Trauma Resolution. I also treasure (unread and unbought for now, nonetheless I slavver for) Bill Bryson’s The Body: A Guide for Occupants—in pregustation that he has already written the book I meant to be my next poetry book. True, a slight difference between prose and poetry, I guess. Or should I be saying poetry is different than prose…. (And if you noticed, I just made up my own spelling: ‘slavver’ for ‘slaver’. The reverberations of the latter spelling are just too painful to go near.)

Yet I cannot read anything for the moment but one book, in the traditional sense of read, because all my time except at the kitchen sink is spent on reading about the comportment—i.e. behaviour and misbehaviour, escapades, illegalities and acquired honorifics, linguistic prowess and sexual liberties—of the coureurs de bois, their shifting relationships with the Ancien Régime and with the Indigenous societies they so often lived among (though with horror I read the word ‘slave’ slipping in there with the lightest touch), and on solving the variants in translation of First Nations’ tribal names from one of their way-more-than seventy languages into seventeenth century French into twenty-first century English. I am in the ring with one book, for now, all 850 pages of it, wrestling its translation to the ground, and it’s plenty big enough for me.

Mia Anderson has published six books of poetry. She has been an actress, organic grower and market gardener, shepherd, priest, poet and translator. Several of these things she still is.

Photo courtesy of Mia Anderson. Cover photo by Matteo Maretto.

Tanya Bellehumeur-Allatt’s Writing Space

Even when we have lots of friends or family over, no one sleeps in my studio, because I like to write in the early morning. I also need somewhere to escape to when the house is full.

I’ve got all my projects here, in binders and folders and on bits of paper scattered all over my desk. All my characters surround me. I’ve got my favourite books here, too, as well as my cello and my yoga mat, for when it’s time to take a break.

There’s a couch, too, for reading or napping.

But what I do most is sit at my desk. It’s part of my writing routine. When I sit here, it’s time to work. My brain kicks into gear, whether I’m typing at my computer or scribbling in my journal. Writing happens.

Tanya Bellehumeur-Allatt has been published in Best Canadian Essays 2019 and 2015, Grain, EVENT, Prairie Fire, Malahat Review, Antigonish Review, and Room. She holds an MA from McGill and an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC.

Photo courtesy of Tanya Bellehumeur-Allat. Cover photo by Shona Corsten.

What is Sarah Wishloff Reading?

It’s a question that, like all well-intentioned literary curiosities—what’s your process? How did you come to this piece? What are you writing? —makes me feel fraudulent and a little bit sad. I haven’t been reading. I can’t remember the last time I read a book cover to cover.

Like a lot of would-be writers, I was an avid child reader. Picture me the way Alexander Chee describes his younger self: “hiding from the world around me inside of books that I loved and building a fortress out of those books, which I lived inside of.” I spent my summers in between stacks at the public library. I happily spoiled my eyes reading at night by the crack of hallway light coming under my bedroom door. Kenneth Oppel’s Airborn—the story of an airship cabin boy who, unable to adjust to life on earth, transcends his lowly status by discovering a magical creature no one else can see (while fighting off sky pirates, obviously)—gave way to science-fiction favourites like Isaac Asimov’s Caves of Steel and Kurt Vonnegut’s Sirens of Titan. Books were a way of escaping life: things that made me feel safer and better understood even as they enabled me to withdraw from the reality around me. I still remember reading 1984 and feeling like I was seeing colour for the first time.

I could blame my failure to read on the pandemic, but the truth is I haven’t been able to concentrate, haven’t felt quite myself, for a few years now. There’s something anxious growing in my chest that always stops me from pulling anything new off the shelf. A thick, eating anxiety that takes up altogether too much space inside me and watches the list of books I ought to be reading and stories I ought to be writing grow monstrous. Lately, when I get off work all I ever want to do is lie down.

Still, I haven’t stopped chewing on the same bits and pieces from favourite poems and novels. I keep tonguing the phrase, rotten, perfect mouth, from Eva H.D.’s “Teenage Stuff Forever.” I find myself reflexively pulling up Jody Chan’s “Syntax Lessons,” or clicking through the selected publications on their website. I’ll start to re-read poems from Cameron Awkward-Rich’s Sympathetic Little Monster again (and again). Or flip through old books until I find the one line that still haunts me. (Most recently, But I have seen the city do an unbelievable sky, from Toni Morrison’s Jazz).

Despite my inability to concentrate or address the abundance of untouched and half-finished books on my shelves, there’s something comforting about knowing my body still craves language. I suppose what I’m looking for now is the same thing I found in all those science fiction novels I consumed as a kid: recognition, and just a little bit of beauty.

Another scrap I keep turning over is the inscription Cameron Awkward-Rich left in my copy of Sympathetic Little Monster: “Thanks for wanting to bring my words home—hope I continue to offer something you need.” something you need. This, at least, remains true.

Sarah Wishloff is a queer artist and writer currently living in Edmonton, Treaty 6 territory. She works in many circles from the non-profit sector to mental health and activist communities. She only cooks comfort food.

Photos courtesy of Sarah Wishloff; Debby Hudson; and Jens Thekkeveettil.

Finding the Form With Matthew King

I remember the first time I identified a poem as an irregular sonnet: it was Robert Frost’s “For Once, Then, Something”, which was in an anthology we used in one of my highschool English classes. I don’t know why I thought it was a sonnet; I just remember insisting that it was. Now, having more experience of the appearance of these things, when I see a poem with that almost-square look on a third of the page or so, the first thing I do is count the lines–fifteen, it turns out, in the Frost poem; close enough. A regular five feet per line, too, unrhymed, but not the familiar Frostian blank verse: a trochee, a dactyl, then three more trochees, eleven syllables per line, like clockwork. (I can’t stop counting on my fingers as I re-read what I’ve written here.) And a turn announces itself, too, but soon, as the seventh line begins, emphatically: Once.

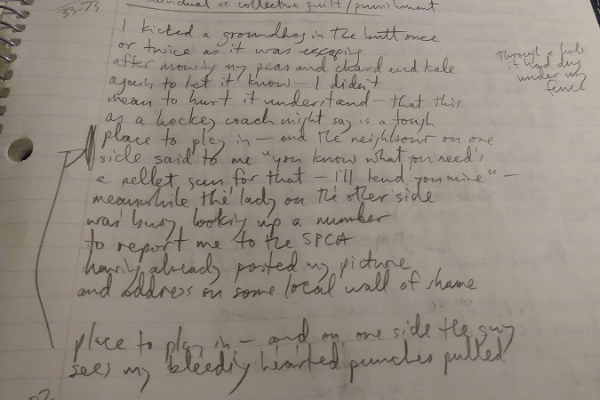

I used to say it was an arbitrary life-goal of mine to write as many sonnets as Shakespeare. Some poems are easier to count toward that than others. Should I count “Yes, I Kicked a Groundhog in the Butt Once”? Arguably it’s basically a blank-verse sonnet, but its feet are running all over the place, maybe befitting such a rambling little yarn (which turns one way, then another)–truth be told, it’s really more decasyllabic than pentametric. It got to be that way because it was always going to start with “I kicked a groundhog in the butt once”, which needed just a little affirmation to work itself up into a nice line of pentameter. From there, the rest of the story (which is admittedly a half-imagined mash-up–the lady calling the SPCA is only a personification of my own superego, and the guy with the pellet gun was, in real life, talking about chipmunks) told itself, fortuitously enough, in thirteen more just-about-ten-syllable chunks–and there I had it, that respectable sonnet-esque look. It ends with a rhyming couplet, but as a coda to its fourteen-line body, the moral of the story, signalling that it’s more comment than content by separating itself and dropping a syllable in each sing-songy, just-so line.

Well, this is a pretty serious take on such a goofy little poem. But it’s a goofy little poem on some serious business. I don’t mean the business of maybe getting strung up for animal cruelty because I kicked a groundhog in the butt once or twice (which indeed I did); I mean the business of investing yourself in some precarious thing, which you were always afraid was nothing but ridiculous anyway, then watching as something, making a mockery of your defensive pretenses, comes along and destroys it all in minutes, munch-munch-munch, carrying out a phenomenological reduction of your endeavours to their essential vanity. As Hegel writes (and this is his only published joke, as far as I know, but it’s a good one), non-human animals demonstrate that they are “profoundly initiated” into an ancient wisdom about the non-being of the things of sense-experience when “they do not just stand idly in front of sensuous things as if these possessed intrinsic being, but, despairing of their reality, and completely assured of their nothingness, they fall to without ceremony and eat them up.” Back when I would see rabbits robotically consuming the grass at the side of the path as I walked home from my graduate seminars, it amused me to think of the rabbits as little Hegelian nihilists, but the joke wasn’t so funny anymore when I started trying to grow things–not so much for me to eat as to make something of myself–and the annihilating rodents showed up, cutting me down to size.

Shakespeare didn’t actually write a huge number of sonnets: 154, officially, so, at, say, one a week, I would’ve achieved my old arbitrary life-goal in about three years. The poetry-writing goals I have these days seem to me a whole lot less arbitrary; my defenses are a whole lot more pretentious. The groundhogs are hibernating as I write, but they’ll be back, again and again, to eat up the fruits of my labours. And I still–I hope–won’t have the heart to really hurt them.

Photos courtesy of Matthew King and Gary Bendig.