Uncategorised

What is Sarah Wishloff Reading?

It’s a question that, like all well-intentioned literary curiosities—what’s your process? How did you come to this piece? What are you writing? —makes me feel fraudulent and a little bit sad. I haven’t been reading. I can’t remember the last time I read a book cover to cover.

Like a lot of would-be writers, I was an avid child reader. Picture me the way Alexander Chee describes his younger self: “hiding from the world around me inside of books that I loved and building a fortress out of those books, which I lived inside of.” I spent my summers in between stacks at the public library. I happily spoiled my eyes reading at night by the crack of hallway light coming under my bedroom door. Kenneth Oppel’s Airborn—the story of an airship cabin boy who, unable to adjust to life on earth, transcends his lowly status by discovering a magical creature no one else can see (while fighting off sky pirates, obviously)—gave way to science-fiction favourites like Isaac Asimov’s Caves of Steel and Kurt Vonnegut’s Sirens of Titan. Books were a way of escaping life: things that made me feel safer and better understood even as they enabled me to withdraw from the reality around me. I still remember reading 1984 and feeling like I was seeing colour for the first time.

I could blame my failure to read on the pandemic, but the truth is I haven’t been able to concentrate, haven’t felt quite myself, for a few years now. There’s something anxious growing in my chest that always stops me from pulling anything new off the shelf. A thick, eating anxiety that takes up altogether too much space inside me and watches the list of books I ought to be reading and stories I ought to be writing grow monstrous. Lately, when I get off work all I ever want to do is lie down.

Still, I haven’t stopped chewing on the same bits and pieces from favourite poems and novels. I keep tonguing the phrase, rotten, perfect mouth, from Eva H.D.’s “Teenage Stuff Forever.” I find myself reflexively pulling up Jody Chan’s “Syntax Lessons,” or clicking through the selected publications on their website. I’ll start to re-read poems from Cameron Awkward-Rich’s Sympathetic Little Monster again (and again). Or flip through old books until I find the one line that still haunts me. (Most recently, But I have seen the city do an unbelievable sky, from Toni Morrison’s Jazz).

Despite my inability to concentrate or address the abundance of untouched and half-finished books on my shelves, there’s something comforting about knowing my body still craves language. I suppose what I’m looking for now is the same thing I found in all those science fiction novels I consumed as a kid: recognition, and just a little bit of beauty.

Another scrap I keep turning over is the inscription Cameron Awkward-Rich left in my copy of Sympathetic Little Monster: “Thanks for wanting to bring my words home—hope I continue to offer something you need.” something you need. This, at least, remains true.

Sarah Wishloff is a queer artist and writer currently living in Edmonton, Treaty 6 territory. She works in many circles from the non-profit sector to mental health and activist communities. She only cooks comfort food.

Photos courtesy of Sarah Wishloff; Debby Hudson; and Jens Thekkeveettil.

Finding the Form With Matthew King

I remember the first time I identified a poem as an irregular sonnet: it was Robert Frost’s “For Once, Then, Something”, which was in an anthology we used in one of my highschool English classes. I don’t know why I thought it was a sonnet; I just remember insisting that it was. Now, having more experience of the appearance of these things, when I see a poem with that almost-square look on a third of the page or so, the first thing I do is count the lines–fifteen, it turns out, in the Frost poem; close enough. A regular five feet per line, too, unrhymed, but not the familiar Frostian blank verse: a trochee, a dactyl, then three more trochees, eleven syllables per line, like clockwork. (I can’t stop counting on my fingers as I re-read what I’ve written here.) And a turn announces itself, too, but soon, as the seventh line begins, emphatically: Once.

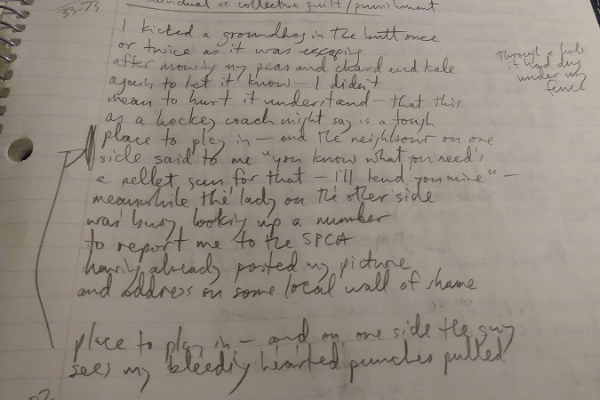

I used to say it was an arbitrary life-goal of mine to write as many sonnets as Shakespeare. Some poems are easier to count toward that than others. Should I count “Yes, I Kicked a Groundhog in the Butt Once”? Arguably it’s basically a blank-verse sonnet, but its feet are running all over the place, maybe befitting such a rambling little yarn (which turns one way, then another)–truth be told, it’s really more decasyllabic than pentametric. It got to be that way because it was always going to start with “I kicked a groundhog in the butt once”, which needed just a little affirmation to work itself up into a nice line of pentameter. From there, the rest of the story (which is admittedly a half-imagined mash-up–the lady calling the SPCA is only a personification of my own superego, and the guy with the pellet gun was, in real life, talking about chipmunks) told itself, fortuitously enough, in thirteen more just-about-ten-syllable chunks–and there I had it, that respectable sonnet-esque look. It ends with a rhyming couplet, but as a coda to its fourteen-line body, the moral of the story, signalling that it’s more comment than content by separating itself and dropping a syllable in each sing-songy, just-so line.

Well, this is a pretty serious take on such a goofy little poem. But it’s a goofy little poem on some serious business. I don’t mean the business of maybe getting strung up for animal cruelty because I kicked a groundhog in the butt once or twice (which indeed I did); I mean the business of investing yourself in some precarious thing, which you were always afraid was nothing but ridiculous anyway, then watching as something, making a mockery of your defensive pretenses, comes along and destroys it all in minutes, munch-munch-munch, carrying out a phenomenological reduction of your endeavours to their essential vanity. As Hegel writes (and this is his only published joke, as far as I know, but it’s a good one), non-human animals demonstrate that they are “profoundly initiated” into an ancient wisdom about the non-being of the things of sense-experience when “they do not just stand idly in front of sensuous things as if these possessed intrinsic being, but, despairing of their reality, and completely assured of their nothingness, they fall to without ceremony and eat them up.” Back when I would see rabbits robotically consuming the grass at the side of the path as I walked home from my graduate seminars, it amused me to think of the rabbits as little Hegelian nihilists, but the joke wasn’t so funny anymore when I started trying to grow things–not so much for me to eat as to make something of myself–and the annihilating rodents showed up, cutting me down to size.

Shakespeare didn’t actually write a huge number of sonnets: 154, officially, so, at, say, one a week, I would’ve achieved my old arbitrary life-goal in about three years. The poetry-writing goals I have these days seem to me a whole lot less arbitrary; my defenses are a whole lot more pretentious. The groundhogs are hibernating as I write, but they’ll be back, again and again, to eat up the fruits of my labours. And I still–I hope–won’t have the heart to really hurt them.

Photos courtesy of Matthew King and Gary Bendig.

What is K.D. Miller Reading

I have just finished the novel Jack by Marilynne Robinson. It is the fourth book in a series which began in 2004 with Gilead, a short novel Robinson herself feared might be unpublishable, but which in fact won the Pulitzer Prize.

Having now finished the series (though there are hints of a fifth book in the making) I am left with two questions. First, why are things like goodness, kindness and forgiveness so seldom the topic of modern fiction? And a related question: why do I find it so difficult, when I love and admire an author’s work, to articulate exactly why? I guess what I’m asking, in both cases is, why does the positive so easily elude us?

I can understand why Robinson feared the first book, Gilead, might never get into print. In terms of what is fashionable, what sells, the novel has just about everything going against it. Set in in small-town Gilead, Iowa in 1956, it is told in the voice of the Reverend John Ames, an elderly church pastor who is dying of heart failure. He is writing a letter to the 5-year-old son he has by his much younger wife, Lila, and whom he knows he will never see grow up. Not the stuff of page-turners, I assumed, when I first took it on.

Well. I’ve read it three times. Each time, it has gotten bigger, wider, deeper and more baffling. Spiritually, emotionally, intellectually, the book overwhelms me. And I am astonished at Robinson’s courage in writing from such an unabashedly religious point of view. In the words of John Ames: “There is no justice in love, no proportion in it, and there need not be, because in any specific instance it is only a glimpse or parable of an embracing, incomprehensible reality. It makes no sense at all because it is the eternal breaking in on the temporal. So how could it subordinate itself to cause or consequence?” Again, not exactly the stuff of best-sellers. And yet that is what Gilead became. So maybe there is balm therein.

The novels that followed – Home; Lila; and now Jack – have been compared to the Gospels, in that they tell the same story four different ways. This story involves three families, one of them Black. We meet John Ames, his wife Lila, his best friend Robert Boughton, Boughton’s son (and Ames’s godson) Jack, Jack’s sister Glory and finally Jack’s common-law Black wife Della. The latter pair cannot marry, given the miscegenation laws of the time. Despite their depicting an America of almost seventy years ago, the books are remarkably relevant to the present, dwelling as they do on racism, violence and the difficulty of having any kind of faith.

The series began when Robinson made the imaginary acquaintance of John Ames. In her own words, : “… I felt engaged by the character – his voice, his mind. I liked listening to him. He was such good company that I missed him when I had finished writing.” As a writer, I can so relate to that. We do have a relationship with our made-up people – one that feels very real. And when a book is finished, we do miss the sensation of following them around, seeing what they get up to, listening to what they have to tell us. I can only imagine the fun she had with Jack Boughton, protagonist of the latest book in the series. Read from his standpoint, the cumulative story is a retelling of the parable of the prodigal son – a remarkably unrepentant one. Here is Jack’s summing up of himself: “I’m a gifted thief. I lie fluently, often for no reason. I’m a bad but confirmed drunk. I have no talent for friendship. What talents I do have I make no use of. I am aware instantly and almost obsessively of anything fragile, with the thought that I must and will break it. This has been true of me my whole life. I isolate myself as a way of limiting the harm I can do.” And yet Jack is loved. By his father, his godfather, his sister and his wife.

Once again, while I can’t recommend all four of these books highly enough, I have to depend on others to articulate why. So here is Barack Obama’s take on their author: “[She is] unashamed to reach for big themes and big questions – about how we give our lives purpose, and how we deal with death and what it means to be redeemed from the mistakes and flaws of our lives. There’s a fundamental compassion and a deep humanity rather than cynicism about people that runs contrary to what a lot of our art these days reflects.”

K.D. Miller’s stories and essays have appeared in Canadian literary magazines, have been collected in Oberon’s Best Canadian Stories and The Journey Prize Anthology, and have been broadcast by the CBC. She has published five collections of stories, an essay collection, a novel, and a chapbook of poems. In 2014, All Saints was short-listed for the Rogers Writers Trust Award and named as one of the year’s best by the Globe and Mail. Her latest story collection, Late Breaking, was inspired by the paintings of Alex Colville. It was named one of the best of 2018 by the Globe and Mail, short-listed for the Trillium award, nominated for the Toronto book award, nominated for the Giller prize and short-listed for the Governor General’s Award.

Photos courtesy of K.D. Miller, Julien de Salaberry, and Àlex Rodriguez.

Finding the Form with Doretta Lau

I began writing “All the Dreamers on the Run” in 2012, when I was working on How Does a Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun?, my short story collection. At the time I was living in Hong Kong and I was inspired by the Sheung Wan neighbourhood, which was in walking distance of my one-hundred-square-foot apartment. From the start, I knew that I was working on a short story about a man who is ambivalent about his relationship with his girlfriend. The original title was “High Tide.”

Before I could start writing, I needed to visualize the tarot reading that is at the heart of the story. I laid out all the cards I wanted to describe within the narrative, and then asked a friend, M. Paramita Lin, to confirm whether this combination produced a real reading. Then I wrote several drafts of the first thousand words. By 2013, I’d abandoned the story—I had all these notes and ideas, but the ending was unclear so I had no direction. There was no spark.

In July 2020, during a long stretch of obeying stay-at-home orders in Vancouver, I decided to return to this story. I’d promised editor Vinh Nguyen an essay about what life was like in Hong Kong at the beginning of the pandemic in February, but I was tired of talking about Covid-19. Instead, I wanted to return to a time before everyone had a smart phone, to revisit an era where Kanye West had no political aspirations, and to remember what life was like before people spent more time on social media than socializing in person. My inclination is always to turn to fiction, especially short forms, to best express my ideas.

As I recalled what life was like in 2010, when “All the Dreamers on the Run” is set, I remembered an essay by Jay McInerney on the Strokes, which I’d read around that time. This gave me material to work with for my character Gideon’s ambitions and dreams vs his reality. With each new draft, it became apparent that the title “High Tide” was no longer serving the story. M. Paramita Lin told me to look for the title in song lyrics. While on a walk I was listening to the debut Julian Casablancas album and “11th Dimension” started playing. That’s when the title came to me:

“That is how it once was done

All the dreamers on the run.”

Once I resolved the title, everything came together. From there, I moved onto line edits, working hard to imbue each sentence with the feeling of that era in Hong Kong. For me, every short story is structured around reaching a point of emotional change, no matter the setting or the characters involved. It was important to me that I ended this narrative with movement, and the desire to be part of something greater than the self.

Doretta Lau is the author of the short story collection How Does A Single Blade of Grass Thank the Sun? and the poetry chapbook Cause And Effect. She is working on a comedic crime novel set in a theme park devoted to death, dying, and the afterlife. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Photos courtesy of Doretta Lau.

What is Ian Roy Reading?

In the early days of the pandemic, back when everyone was baking bread and doing puzzles, a friend on social media tagged me in one of those ‘name-ten-books-that-changed-your-life’ posts. I usually ignore these things because they make me anxious. Just ten? Changed my life how? And they usually instruct one to simply post the cover with no further explanation. Like that was going to happen.

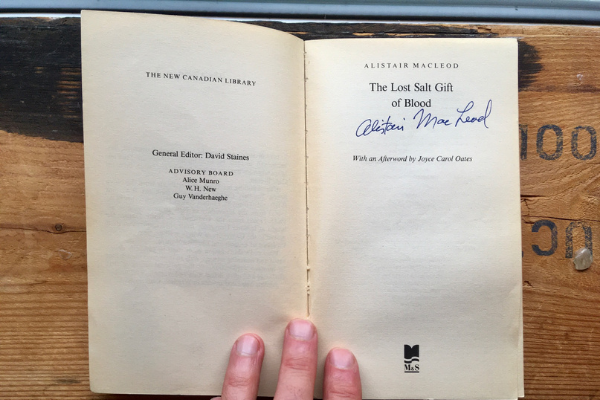

I ignored it for a few days, but of course I was left thinking about which books I would include on such a list. I eventually decided to play along. It was fun to revisit a handful of books that I have loved and that have stayed with me over the years. Judy Blume’s Then Again Maybe I Won’t (a classic that I will always love) made the list, as did Margaret Laurence’s The Diviners (a novel that contains perhaps the best cuss in all of literature). At the top of the list was Alistair MacLeod’s The Lost Salt Gift of Blood, an absolutely perfect collection of stories (I won’t even qualify that with an “in my opinion”).

I can’t take that Alistair MacLeod book off my shelf and not reread it. So that’s just what I did.

I love the title of this book. I remember the first time I saw it in a bookstore. I read the title out loud several times, causing customers and staff alike to keep an eye on me, no doubt. What does it mean? I wondered (and probably also said aloud). What could it possibly mean?

So much, it turns out.

Part of what MacLeod’s fiction is about is slowing down and simply telling a good story. His voice—his literary voice—is so conversational, so casual, you can’t help but be drawn into his stories. And his sentences… they appear so effortlessly perfect, so precise. I once typed out an entire story from this collection (“The Boat”) just to see how it worked on a word by word, sentence by sentence level. Every single word in every one of his stories is crucial, is necessary: there is nothing on the page that shouldn’t be there, that doesn’t move the story forward. I learned to slow down (as a writer) by reading his work; I learned to trust the story and let it unfold.

The first time I read this book, I was living in Halifax. I heard that Alistair MacLeod would be reading at the old library on Spring Garden Road. I told my boss I had a doctor’s appointment and ran across town to catch the reading. MacLeod read a story from The Lost Salt Gift of Blood and talked a little about writing. It was fantastic. Afterwards, someone in the audience asked for writing advice. In a deep, commanding voice, MacLeod said two words: Don’t obfuscate. And then he laughed. It was a wonderful laugh.

Ian Roy is the author of four books, including his most recent collection of stories, Meticulous, Sad, and Lonely. He is currently working on a novel for children.

Photos courtesy of Ian Roy and Hans-Peter Gauster.

Exorcism and Catharsis: Finding the Form with Tanya Bellehumeur-Allatt

I knew from the start that “Terrorist Mythologies” needed to be a personal essay weaving together various narratives in what I think of as a braided structure. I’m haunted by the Sabra and Shatila Massacre and have written about it from many different angles. This time, I wanted to juxtapose my own experience as a twelve-year-old Canadian girl in Beirut in the winter of 1983, a few months after the massacre, with the kidnapping and torture of Terry Waite, in a Shia stronghold in southern Beirut. Between these two accounts, I wanted to interweave the harrowing story of Sami, the Palestinian baby adopted by another U.N. family in Beirut and brought to Canada where he grew up for eighteen years until the day after 9/11, when he was brutally mugged at the Richmond Hill gas station where he worked. As his attackers kicked his broken body, they accused Sami of being responsible for the terrorist acts on New York’s twin towers. They told him to go back where he came from.

A braided essay form allowed me to provide the background information and cover the span of time necessary to tell each of these stories. The first part begins in 1982, in Israel, with the plan to adopt Sami from the camps. It then moves to Beirut on April 18, 1983, a day when two pivotal events happened at almost the same time, near one o’clock in the afternoon: the American Embassy was bombed, representing the biggest attack on American diplomacy since WWII, and Sami was born.

The essay traces my family’s history with Sami and his parents, once we return to Canada and attempt to rebuild our lives after spending seven months in a theatre of war. Interwoven with our story is the remarkable testimony of Terry Waite, who was imprisoned in Beirut for almost five years, in complete darkness in solitary confinement, chained to a radiator. After surviving this harrowing experience, Waite found the courage to return to Beirut twenty-five years later, to forgive those who had kidnapped and tortured him.

The essay is ultimately about returning to Beirut: to make peace with memory, to determine never to forget. It spans almost forty years—from the time I was twelve until now. I think of it as a literature of witness, commemorating the more than three thousand men, women and children who were brutally murdered in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. I titled it “Terrorist Mythologies” to highlight the myths we invent to justify acts of terrorism and hatred. Mostly, I wrote it in an attempt to help myself understand what really happened. It is both exorcism and catharsis.

Tanya Bellehumeur-Allatt has been published in Best Canadian Essays 2019 and 2015, Grain, EVENT, Prairie Fire, Malahat Review, Antigonish Review, and Room. She holds an MA from McGill and an MFA in Creative Writing from UBC.

Photo by Artin Bakhan on Unsplash

What is Anne Marie Todkill Reading?

My husband asks whether the fluctuating contents of a stack of books in the living room could be dispersed to their rightful positions, organized by genre, subject, author, and editor, in our various bookcases. Nope, I reply. Hands off. I’ll lose track of them. My anxiety is that my intention to read, or finish reading, these particular books will be waylaid by any number of distractions, and my reading plan will fall apart. The pile in question contains (1) necessary reads or re-reads for research, or to revisit ideas; (2) books bestowed by others; (3) books I think will be good for me; (4) books ordered in the flush of an enthusiasm; (5) books by friends and friends of friends. To each category a certain deference is attached. The living-room book pile is a place of honour.

For my husband, whose career was spent in libraries, the anxiety is not so much that he will lose track of certain books as that he’ll never be aware of their existence in the first place. For him, locating something to read should be achievable by means of either searching or browsing. The success of either method relies on keeping a collection in order. He seems to think I’m hiding the books in my ever-growing stash of “must read next.”

There might be something to that.

Applying my categories to the living-room stack yields: (1) a book about the ecology of forests, another about the early history of forestry in North America, and a report on a forest survey conducted in Ontario in 1911; Anna Reid’s Leningrad (2011), a history of the siege; (2) The Best American Food Writing 2019, guest edited by Samin Nosrat (a gift from my nephew; a terrific collection of sociocultural reflections in which cuisine is secondary); Index Cards (Moyra Davey, 2020); (3) These Truths: A History of the United States (Jill Lepore, 2018); (4) Rosemary Ashton’s life of George Eliot (1996; the only joint purchase in the bunch, and so I really shouldn’t be hoarding it); (5) Annie Ernaux’s electrifying memoir The Years (2020), translated from the French by the Canadian writer, Alison L. Strayer, an old friend of mine who lives in Paris; and two wonderful poetry chapbooks, New Year Letter (A. H. Jernigan) and The Great Fire of Main-à-Dieu: Poems from Clarence the Welder (Anita Lahey, illustrations by Pauline Conley), both exquisitely produced in 2020 by Baseline Press (London, Ont). The Years and Index Cards are in the austere bindings of Fitzcarraldo Editions, an independent publisher of contemporary fiction and long-form essays founded in London (UK) six years ago.

“My anxiety is that my intention to read, or finish reading, these particular books will be waylaid by any number of distractions, and my reading plan will fall apart.”

The book I’m sunk into most deeply right now is Moyra Davey’s Index Cards, a collection of essays of which the most pertinent here is “The Problem of Reading.” Davey is the Canadian-born, New York–based photographer, filmmaker, and writer whose solo exhibition The Faithful is at the National Gallery of Canada until January 3, 2021. Index Cards arrived in the mail through the kindness of Alison Strayer, who is also an old friend of Davey’s – with whom I’m acquainted only at this remove. (Books, friendships, Venn diagrams.) Davey describes the “recurring dilemma” of deciding what to read next, the idea that if one “can simply plug into the right book then all will be calm, still, and right with the world.” She cites an email from Strayer, who articulates a similar feeling: “It seems that when one has answered the question ‘what to read?’ one has solved all the problems of restlessness, unfocus, and hunger of a certain sort,” since any reading “always contains the seeds of future readings.” I, too, am soothed by this settled-in state, the permission one grants oneself to pour time into a book that, in one way or another, is likely to further a project or a line of thought. Davey reflects on the satisfactions of a “productive” or “generative” kind of reading, reading done “as Virginia Woolf put it, ‘with pen & notebook,’ the [kind] that implies a relation to writing, to work.” But she also defends (and who doesn’t?) reading without design, as in the unprogrammed reading of youth, chance finds, tangents, escapes, and “rubbish reading.”

Index Cards is to a large extent the product of reading undertaken “with pen & notebook.” Davey blends memoir, autofiction, diary entries, critical analysis, and commonplace book in ways that are raw, neurotic, earthy, cryptic, circular, exhausting, and brilliant. “Notes on Photography and Accident” fills me with the same exhilaration as did my first readings of Sontag and Barthes on photography and makes me aware of theorists and practitioners I didn’t know. Other pieces draw on an eclectic mix of authors and associated preoccupations. To take a small sample: James Baldwin, Italo Calvino, Walter Benjamin, Jorge Luis Borges, Jane Bowles, Jean Genet, Natalia Ginzburg, Janet Malcolm, Susan Sontag, Mary Wollstonecraft. Davey refers to “a flânerie of reading that can be linked to the flânerie of a certain kind of photographing. Both involve drift, but also purpose.” But her analytical, cross-referenced catalogue of reading and concepts is neither aimless nor idle. For one thing, reading and writing provide a route out of an impasse with her first métier, photography.

Davey ends “The Problem of Reading” with a resolution to tidy up her bookshelves, not-so-secretly hoping that “something forgotten, something irresistible” will come into view and deflect her from the task. As for me, anything might happen between the time I find a permanent place for Index Cards on a bookcase and return to my stack of readerly intentions.

Anne Marie Todkill’s poetry, short fiction, and essays have appeared in various Canadian literary magazines. Her first collection of poetry will be published by Brick Books in 2022.

Photos courtesy of Maksym Kaharlytskyi and Susan Yin.

Mia Anderson’s Writing Space

It looks from photo #1 as if you’ve spent the night in the attic spare room, and you’re on your way down the colimaçon stairs to see if I’m at work at my desk, perched on my stool. You look down and you can see ‘my space’, the main space where poetry happens, but I must be in the kitchen making you coffee. Over the years I have got thoroughly acclimatized to composing on the computer. It used to have to be with pencil and paper. No longer – unless, say, something strikes me sitting by the fire, or at the other end of the house on the sofa at the foot of the bed. Truth be told, I’m probably writing in bed, but I show you just the sofa, photo #2, and its relation to the still-natural world out there: the muse in chief. I situated my desk and stool in photo #1 extremely precisely, so that I would have the view of the fleuve that keeps flowing through my poetry. But I could be out writing on the shore; I’ve certainly been known to do that. Here’s what that might look like – photo #3. You get the picture. I’m a sort of weathervane with only one weather: the one that points my beak out to the fleuve, the great symbol. I’m ex-urban.

Mia Anderson has published six books of poetry. She has been an actress, organic grower and market gardener, shepherd, priest, poet and translator. Several of these things she still is.

Photos courtesy of Mia Anderson and Marko Horvat.

What is Chase Everett McMurren Reading?

Some years back, I learned about the word “tsundoku” in Ella Frances Sanders’s Lost in Translation. Tsundoku is a Japanese noun describing a pile of unread books.

For you, I’ll share handful of partially read, or while-ago read, or up-next books. I currently have six-and-a-half tsundoku surrounding my pandemic-chair (where I meet people virtually for sessions).

Here are the books I wish for all of us to read:

1. Behave by Robert M. Sapolsky — an accessible and adventurous dive into human behaviour

2. Free Play by Stephen Nachmanovitch — a wonderful invitation to make space for improvisation in every-day surviving (and thriving)

3. Light the Dark, edited by Joe Fassler — a nourishing collection of essays on the artistic process by people like Eiizabeth Gilbert and Sherman Alexie

4. A History of My Brief Body by Billy-Ray Belcourt — a hot-off-the-press deeply evocative memoir by Indigenous scholar and poet

5. You’re the One You’ve Been Waiting For by Richard Schwartz — a powerful DIY-way into exploring the many parts of our complicated, tired, beautiful selves

6. The Bloom Book by Heidi Smith — a magical introduction to floral essences and making our ways through these trying times using ancient, Wise-Woman wisdom

7. The Touch of Healing by Alice Burmeister — a delightful, simple how-to guide for using simple, deliberate touch to acknowledge and relieve distress of all sorts

8. Advice for Future Corpses (and Those Who Love Them) by Sallie Tisdale — a wonderful guide for embracing the inevitable (death!) with a bit more ease

Chase Everett McMurren is a queer, Métis, harp-playing, home-visiting physician for elders and a psychotherapist for artists.

Photo courtesy of Jon Tyson.