What is Beth Downey Reading?

Recently, I was out with a clutch of friends—all readerly-writerly types, which tells you something of how spoiled I am in life—when one of our party asked, ‘how do you guys cope with how much there is to read out there?’

How, indeed. In a world heaped with outstanding books, articles, poetry, film, and with friends constantly giving recommendations or sending links or writing books themselves, the hard truth is that one is always, at every moment, missing out and losing ground. “Life piled on life were all too little,” laments Tennyson’s aging Ulysses. I would need several lifetimes to even hope of reading everything I might wish to read, or benefit from reading. In this way, I sometimes think voracious readers confront their personal mortality every time they open or close a book.

Yet—as in the knowledge that death is inevitable and that it will come too soon and that life will end unfinished—one must learn to live, and read, anyway. One must make peace. Which brings me to my friend’s initial question: how do I ever begin to sort out what to read? Now that you understand how provisional my answer is, and that it comes laced with the awareness of its certain inadequacy, you can take it for what it may be worth to you. Godspeed, my friend.

I’m a free-love reader. (Though of course, free love entails the freedom to devote oneself to a single paramour, for a time. As the spirit leads.) Essentially, I try to treat life like one big research project: I keep individual reading lists that pertain to different interests, writing projects, spiritual or intellectual quests, the types of work I’m engaged in, etc. I keep them all separate, usually in my desktop sticky notes, but I also keep them all thrown together in a giant online wish-list, so the almighty algorithms can aid me in seeking out what artists and researchers greater than I have learned about these things. The internet knows books and people you’ve never heard of.

At any given time, I try to keep a bookmark in at least one thing from two or more of my topical lists. My end tables are thus permanently crowded with stacks of books I’m working through all at once, and my tidy, longsuffering husband deserves credit for putting up with this. At the moment, all of the following are somewhere in the soup:

Winter: Five Windows on the Season, by Adam Gopnik. (Gopnik adapted his 2011 CBC Massey Lectures series from these essays.) This is one of a cluster of books that fall under “Making Peace with Pain.” I sought Gopnik out because my husband and I were returning to Manitoba after two transformative years in my ancestral home of Newfoundland; I was torn about the move for many reasons, but one very real reason was that I dreaded the return to Winnipeg winters. Reader, when winter is as long as it is in Winnipeg, hating every minute of it is just no way to live. So I sought help. I’m not through Winter yet, but I am delighted to report that Gopnik’s work has absolutely rocked my world. On a weekly basis, it is transforming my attitude toward both literal and figurative winter.

Also in this category: The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Exploring Desert and Mountain Spirituality, by Belden C. Lane, and Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies of Loved, by Kate Bowler. The first is a raw yet elegant investigation of apophatic theology as taught by harsh landscapes. Dense, by turns academic and confessional, it was recommended to me by our minister, Jamie. Blessed are the discerning book-pushers! As to Bowler, you can get a taste of what you’re in for there through her New York Times article, “Death, The Prosperity Gospel and Me.” One line sold me on the book: “Cancer requires that I stumble around in the debris of dreams I thought I was entitled to and plans I didn’t realize I had made.” Woman, preach.

“For me, audio format is perfect for a first reading, since it encourages me to simply take the book in as a whole, mentally flagging things I want to examine more closely next time.”

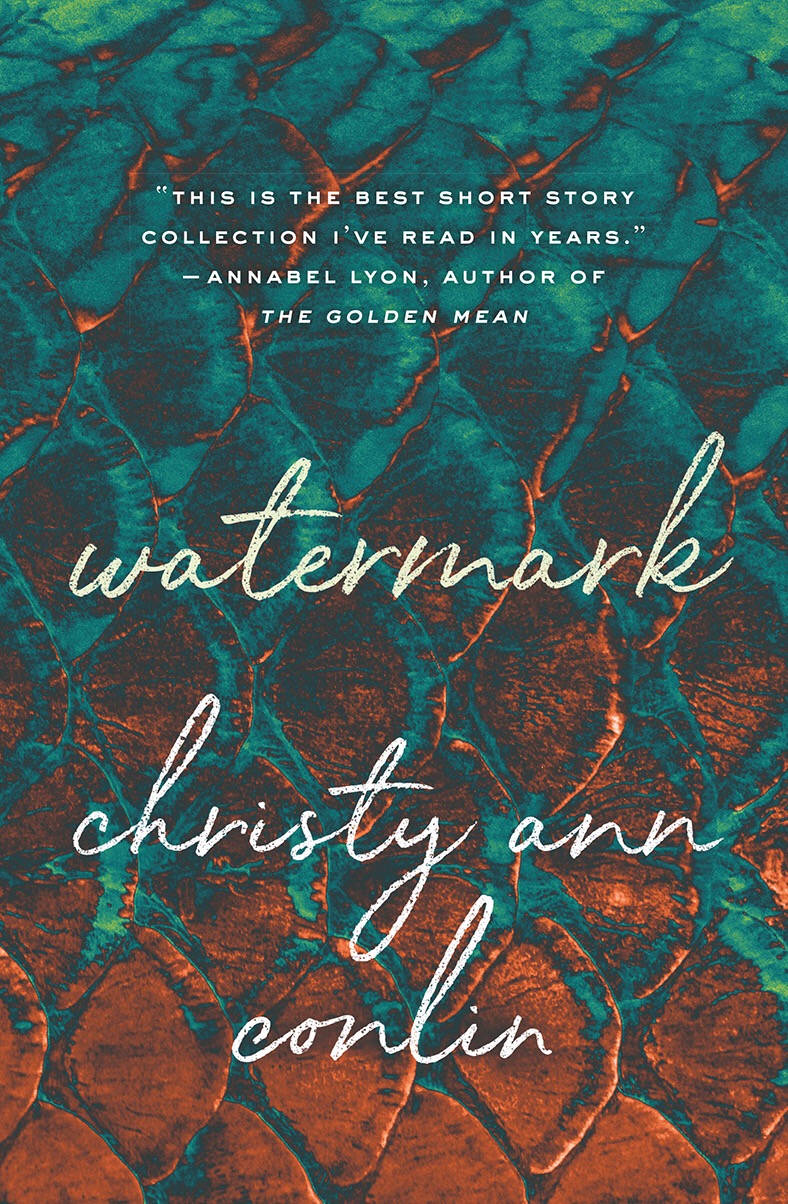

In complement to my own creative writing, I also work freelance as a literary editor, which means I’m often reading something that either isn’t published yet, or just recently hit shelves. Dig by Terry Doyle, is a gritty, observant collection of short fiction about contemporary life in St John’s. Released last year by Breakwater Books, it was a pleasure to work on. I highly recommend it to anybody who wants to cut past the simple, touristic image of local life that you will confront on first visiting St John’s, and glimpse the more greyscale realities through the eyes of an artist who loves his home. This winter, I’m working on a manuscript by rising star Jim McEwan, who was long-listed for the CBC short story prize in 2016, and recently completed an MA in creative writing supervised by Lisa Moore. Jim’s novel, tentatively titled Fearnoch, will soon to be seeking a publisher and b’ys oh b’ys, once this gets out they’ll be tripping over each other to publish the next one. Mark my words.

Lastly, I’ll tell you a bit of what I’m reading to inform my secret novel-in-progress, (shh, don’t tell,) and what for pure, unadulterated fun.

Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy. I’m listening to this one as an audiobook during my daily commute (praise be to LibriVox!) That’s a strategic choice, since I plan to read the book more than once. For me, audio format is perfect for a first reading, since it encourages me to simply take the book in as a whole, mentally flagging things I want to examine more closely next time.

Also for the (secret) novel: Every Monica Kidd poem I can get my hands on. I discovered Kidd through a chance encounter, when she was (and this is delicious) giving a reading from her latest collection, Chance Encounters with Wild Animals, in Winnipeg. I wept through the whole reading—not because the poems were sad, but because they spoke to me so deeply when I had not been expecting it. Tears of rapture!

As to joy (the only way to make an end,) this is almost always going to fall in one of two categories for me: Dickens or Dragons. That is to say, classics or high fantasy. Most recently it’s been fantasy. After, I am ashamed to say, years of my very best friend imploring me to read a little book called The Name of the Wind, by Patrick Rothfus (long may he reign,) and me putting my best friend off with a bunch of (factual) guff about assigned readings and the pressures of grad-school and blah blah blah…I finally read it. The ending made me gasp, and cry, and scream, and jump around my kitchen rejoicing. And now you know what a sterling man my friend is.

Now go my friends! Life is short! Read what you want to read.

Beth Downey is an emerging writer of poetry and fiction, currently dividing life between Winnipeg and St John’s, where she is a graduate student. She also moonlights as a birth doula.

Photo by Erik Mclean on Unsplash.