Uncategorised

What is Ami Sands Brodoff Reading?

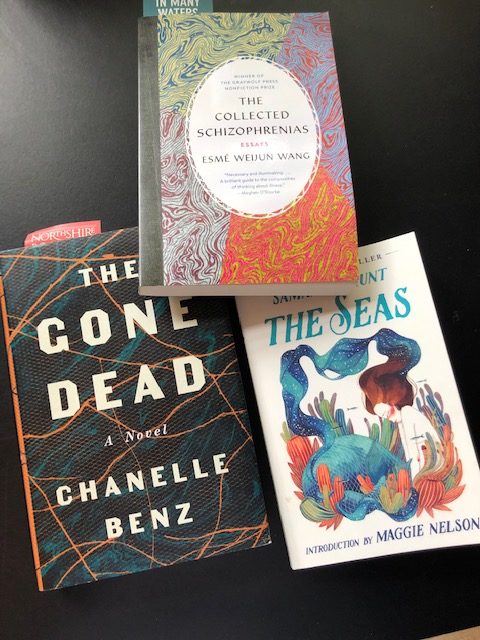

I usually have a few books on the go and fiction is my passion reading. Right now, I’m engrossed in two contemporary novels: The Seas, by Samantha Hunt and The Gone Dead, by Chanelle Benz. I learned about The Seas on a recent rainy day in Vermont while browsing in a lovely independent bookshop, The Northshire. The Seas was among the staff picks with a personal handwritten note by the bookseller who recommended it. I admit I was also drawn to its striking, colourful, and fantastical cover, as well as to the reviews and blurbs. The Seas is hard to classify. The novels pushes the boundaries between fiction and fantasy, myth and reality. It is spare yet gorgeously written in lyrical prose and can be subversive and funny. It’s a tale about a lovelorn girl who may be a mermaid flooded with aqueous themes and enthrallment with the ocean. Anything with water and you have me at hello.

I usually have a few books on the go and fiction is my passion reading. Right now, I’m engrossed in two contemporary novels: The Seas, by Samantha Hunt and The Gone Dead, by Chanelle Benz. I learned about The Seas on a recent rainy day in Vermont while browsing in a lovely independent bookshop, The Northshire. The Seas was among the staff picks with a personal handwritten note by the bookseller who recommended it. I admit I was also drawn to its striking, colourful, and fantastical cover, as well as to the reviews and blurbs. The Seas is hard to classify. The novels pushes the boundaries between fiction and fantasy, myth and reality. It is spare yet gorgeously written in lyrical prose and can be subversive and funny. It’s a tale about a lovelorn girl who may be a mermaid flooded with aqueous themes and enthrallment with the ocean. Anything with water and you have me at hello.

I’m also into The Gone Dead, a can’t put down debut novel. Set in Mississippi, the story centres on Billie James who inherits a shack in the Delta that belonged to her father who died unexpectedly and mysteriously when she was four years old. Her neighbors are a family whose history has been enmeshed with hers since the days of slavery. The story contains varied voices which form a chorus around Billie’s primary voice. Suspenseful and gritty, this novel offers a fresh look at Mississippi’s dark past.

In addition, I’ve loaded Toni Morrison’s oeuvre onto my ipad and plan to revisit this literary lioness’ work in full, especially now that there will be no more Morrison to come.

In addition, I’ve loaded Toni Morrison’s oeuvre onto my ipad and plan to revisit this literary lioness’ work in full, especially now that there will be no more Morrison to come.

I’m also dipping into an extraordinary nonfiction work, The Collected Schizophrenias, essays by Esme Weijun Wang, a raw and powerful first-hand account of navigating psychosis. These pieces will make you question what it means to be well and what it means to be ill.

I keep up with book news and reviews and keep lists of books I want to read in little notebooks I carry with me, so I don’t forget their titles or authors. I read both on paper and ipad or Kindle. The latter is portable and great for travel, having a library in one place. The former can’t be beat for the sensuous pleasures of heft, of turning a page, of finding and rereading an extraordinary passage. But I realize the greatest gift of reading a cloth-bound or paperback book is the concentrated focused attention that it enables. I put my devices away and read.

I begin my day with a bit of reading in bed over coffee and I end my day with more reading in bed over mint tea. After I knock off work on my own writing, I will often do some reading.

I also love audible books, especially when my eyes are strained. I’ll sit out in the park or a café and listen. It takes concentration and is a more drawn out enveloping experience than reading, as many more hours are required to finish a book.

The old me felt forced to finish a book I’d started no matter how bored or frustrated I felt. The new me will give a book about fifty pages, and if it does not engage me, I will put it aside with no Jewish guilt. Life is too short.

I savour a dramatic story with lies and secrets and mysteries to unravel. Attention to language is vital as is layered complicated characters. In short: I want it all.

Ami Sands Brodoff is an award-winning novelist and short story writer based in Montreal. She is at work on a new linked collection, The Sleep of Apples.

Photos courtesy of Ami Sands Brodoff.

Header photo by freestocks.org on Unsplash

What is Rebekah Skochinski Reading?

I have a confession: I’m not in a monogamous relationship… with books. I read everything—often simultaneously: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, piles of literary journals, and I have a zillion tabs open on my computer.

I have a confession: I’m not in a monogamous relationship… with books. I read everything—often simultaneously: fiction, non-fiction, poetry, piles of literary journals, and I have a zillion tabs open on my computer.

I walk to the library several times a week (the librarians at the Thunder Bay Public Library know all of my secrets) and I try to buy books as often as I can. Recently, I read Bunny by Mona Awad, which is a delight: dark, funny, and twisted, in the best possible way. And I also really enjoyed Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman is in Trouble. Having read and admired the celebrity profiles she’s written, and as someone who also writes a lot of non-fiction (I’m the assistant editor of The Walleye—an arts & culture magazine), I was excited to see her foray into fiction. It blew me away. If there were a Temple of Taffy, I would worship.

Currently I’m reading R.O. Kwon’s The Incendiaries. Kwon and I share a similar history in that I also left organized religion many years ago. She’s been vocal about the grief and sense of loss that comes with that, which I can relate to, so I’m eager to get inside the heads of her characters—I’m drawn to any story that has a spiritual component to it.

“I really admire people who can plan out their entire project. I always have to sneak up on it sideways.”

I’m also reading Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative by Jane Alison, which looks at the connections of patterns found in nature. I grew up in a small rural community and spent a lot of time walking through fields and down dirt roads, climbing trees, and swimming in rivers. Since I’m working on the first draft of a novel, I’m hoping it will help me shape it in a way that speaks to my wandering mind. I really admire people who can plan out their entire project. I always have to sneak up on it sideways.

And, what I read every day without fail is a blog: laineygossip.com. I’ve been a faithful reader for over a decade. I love it for the pop culture, fashion, and the Show Your Work podcast, but I’m also there for the gossip. Gossip allows me to figure out what motivates people. What they try to hide and what they choose to reveal. It’s easy to have confirmation bias when it comes to reading: we read what we think we will like. So if I’m learning about someone or a situation that is so far removed from myself and my life, I’m forced to consider where they’re coming from in real time. In that way, I could probably argue, it has made me a better writer. And it’s a major reason I read.

I’m looking forward to digging into new fiction by Cherie Dimaline and Emily St. John Mandel, but I also want to re-read everything by Toni Morrison. Oh, and I just won a book by filling out an online literary matchmaking quiz from Kerry Clare of picklemethis.com. Who doesn’t love getting books in the mail?

I’ll read anywhere: in my backyard, at the doctor’s office, on the couch. When I was a kid, I stayed up well past my bedtime with a housecoat slung over the lamp and a towel wedged under the door so my parents thought I was asleep. Now, if I try to read for any length of time in bed, the only thing that I’m reading are my eyelids. So I get up early and read in the morning. It feels like stolen time. At night is when I sift through my stack of The New Yorker’s and literary journals on my nightstand including the latest issues of Grain, Room, Prairie Fire, The Malahat Review, and The New Quarterly.

Reading saves me from myself. You know how in Scrabble when you decide to exchange your letters so that you can start fresh? Every time I read a book, it gets me out of my head—I feel like I’ve been given a new set of letters and I know how to make words again.

Rebekah Skochinski has been published in various literary journals and recognized in contests both in Canada and the United States. She is working on a collection of short fiction and a novel.

Photos courtesy of Rebekah Skochinski.

Kirsteen MacLeod’s Writing Space

I have a problem for a writer: I hate to sit down for extended periods. It wasn’t always thus, but right now I feel restless, compelled to roam, to seek writing spaces in all corners at home, or outside by the woods or the water, or in public libraries, those treasure-filled temples without which I’d never, ever have become a writer.

When I’m home I might perch the computer on the windowsill in my small yoga studio, seeking ways to make writing a dynamic activity. I’m fond of the view from this window, which includes a cherry tree, a chicken coop with five fluffy birds, and beyond the backyard, a cemetery – an “If not now, then when?” to imbue my days.

When I feel the need for a safe underground writing bunker, which happens more and more in these anxiety-provoking times, I work in my basement study. It features a movable desk that goes from low—sitting cross-legged on the floor—to medium—sitting on an exercise ball or a chair—to standing height. Beside the desk a treadmill collects dust. When I go down there, I set a timer for one hour—upstairs, so I have to run and turn the infernal thing off. This prevents me from losing track of four hours, spine in a C position, not breathing, concentrating hard, which happens regularly despite how much I loathe sitting still and all the yoga I do to remind me to breathe and be conscious of my body.

When I feel most sensitive or beleaguered, I take my rat’s nest of papers and books and write under the duvet of my bed awhile, propping myself up on the pillows.

In brighter times, when the sun is in the west, I write at the front of the house at the kitchen table, a centrifugal mess of papers, books, pens and sticky notes spinning out from my computer. Or I open the front door to let in the light and fold out the cherry leaf of the antique hall table. This blocks the path to the hallway, impeding the progress of others, who look significantly from me to the wall-sized bookshelf in the living room. Like my study the shelf was lovingly built for me with hopes of containing my workspace sprawl. Whichever place, I also pace.

I’m often driven offsite by noise. It’s a myth that living by a cemetery is quiet: the dead require constant lawn care. When mowers drone and leaf-blowers belch I go to write up to the conservation area five minutes’ drive north of my house. I park in front of the reservoir and go for a walk, and then work in the passenger seat of my car, glancing up to see the odd swan, duck or heron take off or land, or I go sit in the window of the Outdoor Centre, saluting the stuffed owls and taxidermied fisher on my way in. And there’s always my cabin by the river.

At times I imagine remaining in one rooted writing space, where I lounge in a comfy chair, perhaps breathing deeply, surrounded by precious and curated objects, having orderly thoughts and writing them down. But for whatever reason, my writing spaces change with my moods, and my moods are in motion.

At times I imagine remaining in one rooted writing space, where I lounge in a comfy chair, perhaps breathing deeply, surrounded by precious and curated objects, having orderly thoughts and writing them down. But for whatever reason, my writing spaces change with my moods, and my moods are in motion.

Photos courtesy of Kirsteen MacLeod.

Header photo by Debby Hudson on Unsplash

The 2019 Peter Hinchcliffe Short Fiction Award Longlist

Thank you to all of our 2019 Peter Hinchcliffe Short Fiction Contest entrants. There was a strong crop of stories this year that pushed the boundaries of tradition. We were struck by the deep complexity of each entry. After thoughtful deliberation, we are proud to announce this year’s longlisted writers and their exceptional stories.

2019 Peter Hinchcliffe Short Fiction Award Contest Longlist

♦ “Bundle of Joy” by Lisa Alward

♦ “He of the Holy Birth” by Jennifer Batler

♦ “The Underside of a Wing” by Paola Ferrante

♦ “Dakhma” by Dean Gessie

♦ “Miss Khokar Goes to Killbear” by Caitlin Hewitt-White

♦ “Touched” by Anna-Marie Larsen

♦ “Visiting Hours are from 5 to 7” by Erin MacNair

♦ “After Walter” by Chris Masterman

♦ “You’re Just Like Me” by Candice May

♦ “Opener” by Kristen Swan Morrison

♦ “Amphibios” by Andrea L. Mozarowski

♦ “Under the Meadow” by Tatiana Peet

♦ “The Pacific” by Justin F. Ridgeway

♦ “Mandala” by Anji Samarasekera

♦ “This is about running in Jerusalem” by Sivan Slapak

Stay tuned…

We will announce the contest finalists on Wednesday, August 28, 2019!

Launched: The Art of Leaving by Ayelet Tsabari

Welcome to the latest instalment of Launched, the series with the scoop on new books by Canadian authors.

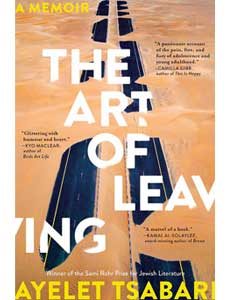

Ayelet Tsabari’s second book, The Art of Leaving, was published earlier this year by Harper Collins. Tsabari is the author of the story collection The Best Place on Earth, which won the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature and the Edward Lewis Wallant Award. The book was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, Kirkus Review’s Best Debut Fiction of 2016, was nominated for The Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, and has been published internationally to great acclaim. Excerpts from The Art of Leaving have won a National Magazine Award and a Western Magazine Award. In 2014, she was awarded a Chalmers Arts Fellowship by the Ontario Arts Council.

Ayelet Tsabari’s second book, The Art of Leaving, was published earlier this year by Harper Collins. Tsabari is the author of the story collection The Best Place on Earth, which won the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature and the Edward Lewis Wallant Award. The book was a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, Kirkus Review’s Best Debut Fiction of 2016, was nominated for The Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, and has been published internationally to great acclaim. Excerpts from The Art of Leaving have won a National Magazine Award and a Western Magazine Award. In 2014, she was awarded a Chalmers Arts Fellowship by the Ontario Arts Council.

Q: Your first book was a short story collection, and The Art of Leaving is a memoir in essays. Some of the essays were previously published in literary journals and anthologies—including “Soldiers”, which first appeared in The New Quarterly. In the acknowledgements, you mention that it took 12 years from when you first began writing the stories from your life until they became a memoir. I’m interested in how you conceived of the book’s ultimate shape, and whether that process was different for essays than it was for your story collection.

I started writing and publishing essays in 2007. I never conceived writing a full-length memoir, because I didn’t think of my life in those terms. The narrative structure felt artificial to me. That’s not how real life works. But I knew I had stories to tell and ideas I wanted to explore, so I started writing essays, one at a time. At some point, it was becoming clear that this could be a book. But something was still missing from it, maybe I needed more distance from certain events to be able to write about them, or maybe I needed some events, like becoming a mother, to actually occur before the book could be completed. That’s why it took me so long. That, and the fact that I wrote my first book—The Best Place on Earth—during that time, too. Once I felt like I had enough essays to compile, I put them together in a somewhat chronological order and tried seeing the book as a whole for the first time: what’s missing, what doesn’t fit, what needs to be established earlier on, what warrants a repetition, etc. Having editors at this part of the process was crucial; they saw big holes in the narrative I couldn’t see for myself and certain thematic threads that were running through the book and needed to be introduced earlier on.

Q: How does it feel to have this intensely personal, wide-ranging, nuanced and—I’ll say it, riveting—book in the hands of readers? What reactions have you had thus far?

Thank you! It’s been an emotional experience. I knew it would be, but you can’t really know how it would feel until it happens. The reactions ranged widely. I’d been blessed by lovely, thoughtful reviews and had people contact me to tell me how much the book resonated with them, and that’s the best feeling. But I’ve also read some hurtful comments (authors should never read Goodreads reviews) like the one where the reviewer commented that my dad (who died when I was nine) was boring. There were people commenting on the story as difficult or too hard to read, which surprised me. I’ve read reviews that passed judgements on the character, which is, of course, a literary representation of my younger self. It can be hard sometimes not to take it personally. Other times it can be amusing. There was one blogger, who loved the book and wrote a kind review, but who called some of my life choices “questionable at best and downright stupid at worst.” I thought that was hilarious. Also, true.

Q: Literary (and Goodreads) criticism or praise aside, how do you think about and deal with the idea of exposure? As a reader, I often feel like I “know” the writer after finishing a memoir, but it’s a false intimacy. And yet, the best CNF makes us feel the writer’s experiences.

It’s an interesting conundrum. As a writer I want you to feel that way. This is a part of the illusion inherent in the genre, the non-fictional dream, if you will. As a person in the world, it can be disconcerting at times to encounter that misconception. But I don’t truly feel exposed. I know the story I tell in my memoir and the characters I create are carefully curated. I chose what to include and what to leave out for the sake of the story (and, at times, for the sake of privacy—mine and others’). I’m a writer. I’m in the business of making art and beautiful things. I’m in the business of story and making meaning out of my experiences.

Q: Navigating languages—native tongue and mother tongue, and your choice to write in English—is a thread running through the book, connecting the myriad ways in which language reflects cultures, values, and perceptions. You write: “English was a place I fled to, an act of reinvention…” It seems like an impossible task, to achieve such mastery of another language. Did you consider continuing to write in Hebrew and having your work translated?

I did start out writing in Hebrew, and I tried translating my work. But translation, while it is a marvelous gift to readers and an amazing skill, always loses something. It is inherent in the act. I’ve had my work translated from Hebrew to English and from English to Hebrew by others, and I’m grateful that I could be involved in that so I could see the places where translation failed, when it changed my voice and even the meaning. But also, by the time I started writing in English I wasn’t using Hebrew in my daily life, so writing in Hebrew didn’t come as naturally to me, either. Language is dynamic. For a language to be alive you need to use it and be surrounded by it, and during those years I no longer was.

Q: Will the book be published in Israel?

For the time being, I’ve decided to hold off on publishing the book in Hebrew. Which stands at odds with my previous statement about not feeling truly exposed, I guess! Somehow, I still feel hesitant about the book being out in the world in my mother tongue, where it can be read by my mom.

Q: What’s next? What are you working on now?

I’m working on a novel, which I find difficult and challenging and exciting. That’s all I can say about it at the moment.

Laura Rock Gaughan is the author of Motherish, a short story collection published in 2018. She lives in Lakefield, Ontario with her family.

The 2019 Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest Longlist

Thank you to all of our 2019 Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest entrants. Your poetry sparked powerful discussion and profound deliberation. Your work was a privilege and a treat to read, and provided us with some of the toughest competition we’ve seen yet. After careful deliberation, we are proud to announce this year’s longlisted poets and their extraordinary poems.

2019 Nick Blatchford Occasional Verse Contest Longlist

♦ “Comrade Birds” by Frances Boyle

♦ “Bumpers” and “Perennial” by Conyer Clayton

♦ “After the Wake” by Beth Downey

♦ “Landscape With the Fall of Icarus” by Cornelia Hoogland

♦ “New Year’s Day” by Heather Kelly

♦ “The Proposal” and “Takatsubo Cardiomyopathy” by Laurie Koensgen

♦ “Ronald’s Driving” by Cory Lavender

♦ “Proposal” by Colette Maitland

♦ “Breach” by Callista Markotich

♦ “Prologue to a Bliss State” by Lisa Martin

♦ “After a long separation” by Maryann Martin

♦ “Shikata ga nai” by Lorin Jane Medley

♦ “The Day I Was Told My Son Had an Intellectual Disability” by Shane Neilson

♦ “The Kindness of Port Angeles” by Deb O’Rourke

♦ “In Winter” by Eleanor Sudak

♦ “Transmission Tower”; “The Commons”; and “Most Days You Still Remember” by Rob Taylor

♦ “On the Publication of My Second Novel” by Sarah Tolmie

♦ “First Knock Down” by Sarah Yi Mei Tsiang

♦ “Letter to Whiskey” by Susan Vernon

♦ “Wrack Zone” by Elana Wolff

♦ “Tender Is the Night” by Terence Young

Stay tuned…

We will announce the contest finalists on

Monday, August 26, 2019!

What is Virginia Boudreau Reading?

You know that uncomfortable feeling of Deja vu that occasionally causes you to pause? It’s one that revisited when the esteemed editorial team at TNQ wondered what book was currently gracing my nightstand. Hmmmmm, I could tell the truth and ignore the nervous rash climbing like an unpruned rugosa up my neck or be unapologetically honest. The irony of it is laughable. Last week I was reading such and such about so and so which was a mind-expanding experience appropriate for one aspiring to be regarded as an actual writer. This week? Not so much.

Alas, the truth wins out but the predicament, eerily familiar, transports me to a time when my kids were young and I was recovering from flu. It was late afternoon and the kitchen was fragrant with a hearty home-made meal simmering and a whole grain bread baking in the oven. There was even a fresh fruit salad waiting in the fridge for afterward because was I a conscientious mom? Absolutely! I was setting the table when a rather humourless young woman showed up at the door wearing a navy peacoat and earnest expression. The Department of Health was in the process of surveying random N.S. households to discern nutrition habits and meal choices. Would I be able to spare a few moments?

“Sure!” I beamed, “Happy to help.” I tried not to sniffle too loudly and looked around my messy kitchen. She pushed her glasses further up on her nose. “I’ll need to know what you served for dinner last night.”

“Last night?” I squeaked. “ONLY last night, not today?”

“We are only looking at meals served on the 13th of January.” A smug gleam flashed when she nodded, aware of my dismay.

The tell-tale blush had already started, and I silently cursed my Celtic colouring. “Well, last night,” I hesitated.

My son, then five, who was following with great interest chirped up. “You remember Mom, last night we had Pizza Pockets!” He was almost bouncing with pride.

Clearing my throat, I attempted to explain. “I really wasn’t up to cooking yesterday, can’t tonight’s meal count instead?”

“Pizza Pockets,” she repeated and recorded it on her clipboard, the satisfied smirk hovering.

“They were good too,” my son chimed in, “and best of all, we had Timbits for dessert, Daddy brought them home!!”

She blinked. I tried again, “But tonight would be much more typical. We’re having….”

“Sorry. I have what I need. The results of this survey will be published in two months time.”

ARGHHHHH!! Why couldn’t she have asked about last Tuesday night?? I couldn’t remember what we’d had, but it definitely hadn’t been Pizza Pockets, because we NEVER had Pizza Pockets at dinner time! She seemed intent on NOT getting that piece though.

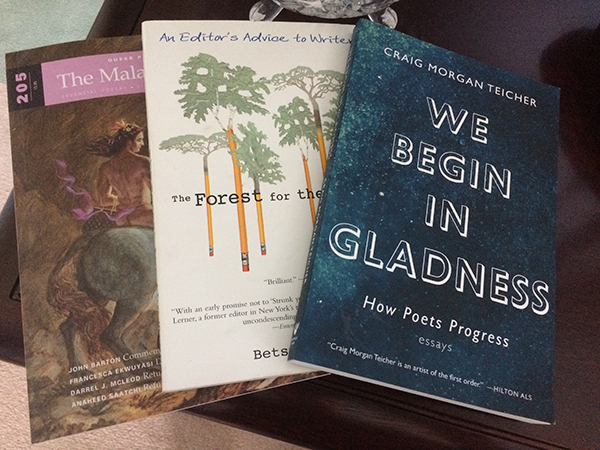

I’d be lying if I didn’t confess I felt similarly conflicted when asked what book I was reading right now. I COULD lie but that would bother me later, so I’ll just have to tell the truth. It’s not the latest issue of The Malahat Review, nor “The Forest Through the Trees, An Editor’s Advice to Writers” by Betsy Lerner, nor is it “ We Begin in Gladness, How Poets Progress,” a series of compelling essays by Craig Morgan Teicher, all of which are presently stacked on my night table waiting to be read. Nope!

The book I’m reading (and loving every moment of) is “Surprise Me” by Sophie Kinsella, an Irish writer. She makes me howl right out loud! I love her voice, her ear for dialogue, her inane cast of characters and the way she explores deeper issues in ways that appear completely effortless. I think she’s a brilliant comedian and a gifted storyteller. It may not be the most intellectually stimulating book I’ve read in a while, but it certainly is the most enjoyable. It’s the one that’s made a hard week better and made me think about how we all probably need a bit more frivolity in a world that’s become increasingly uptight. And, when I think about it, it would be a horrible insult to compare this great read to a measly old Pizza Pocket…or Timbit either, for that matter.

Virginia Boudreau is a retired teacher in Nova Scotia. Her poetry and prose have appeared in international literary publications.

In-text photo provided by Virginia Boudreau.

Cover Photo by Flickr user Geoffery Kehrig.

Finding the Form with Virginia Boudreau

“I must admit, I suffered significant angst wondering if I stole too much ‘heart’ away in the sculpting process. Some passages, relegated to my cemetery of lost words, are committed to rising again some day.”

Poetry has always been my preferred medium and, initially at least, my pieces start out with the intention of becoming some form of poem. The postscripts are no exception, and first drafts (all composed more than ten years ago now) were lengthy narrative poems. This being said, these particular works seemed to require more “breathing space” and a different “look.” It was substantial trial and error that led to the final versions and it helped that I had an excess of raw material to work with.

As a regular subscriber to the Brevity Blog, I’ve become increasingly intrigued with how writers make brief pieces sing. The work in TNQ represents my foray into new territory. I’ve learned I’m quite partial to the restraint imposed by the limited word counts in the flash genre. Most of my questions concerned word choice and sentence structure; how did selections impact or alter what I was trying to say? How could I achieve maximum impact with minimum words? Which language was absolutely essential, and which was self indulgent? After, I was amazed both at the amount of phrasing that was discarded and those lines that remained exactly as they’d been first recorded. I must admit, I suffered significant angst wondering if I stole too much “heart” away in the sculpting process. Some passages, relegated to my cemetery of lost words, are committed to rising again some day.

“I’d say the challenge of finding the best structure to express an idea that does not necessarily want to be tamed is somewhat like having an incomplete jigsaw puzzle set up on the table in the corner; you can’t wait to return to complete the elusive image, frustrating and downright painful as that exercise may be.”

The original poems almost seemed to write themselves. Though I’m inclined to begin with verbose free associations and copious expanses of text, it’s rare for me to have such clarity of intent at the inception of a new piece. In this case, I think the ease and accuracy of word flow in the beginning stages can be attributed to specific triggers activated in three separate workshops. The prompts, provided by accomplished facilitators, stirred latent memories that were more powerful than I ever would have imagined, and strong images appeared in quick succession. The final vocabulary decisions were guided by emotion in “Contrived” and “Shadows.” In both of those I felt the need to produce a visceral reaction in myself, if not in others. I felt more removed from “The Backyard Gate” and remember enjoying the word play and symbolism when I was revising that piece.

If I were to make a comparison, I’d say the challenge of finding the best structure to express an idea that does not necessarily want to be tamed is somewhat like having an incomplete jigsaw puzzle set up on the table in the corner; you can’t wait to return to complete the elusive image, frustrating and downright painful as that exercise may be. You know the goal is attainable; all you need to do is align the disparate pieces to conjure something from nothing. It’s like making magic, and, I’ve discovered, it’s why I write.

Virginia Boudreau is a retired teacher in Nova Scotia. Her poetry and prose have appeared in international literary publications.

Photo by Ricardo Gomez Angel on Unsplash

What is K.D. Miller Reading?

Right now I’m reading three books: New and Selected Poems Volume Two by Mary Oliver; Diary of a Dead Man On Leave, a novel by David Downing; and Schadenfreude: The Joy of Another’s Misfortune by Tiffany Watt Smith. I start each morning with two or three of the poems, read a chapter of the non-fiction in the afternoon, then nod off over the novel at end of day.

That poetry / non-fiction / fiction balance is not one I achieve often, much as I’d like to. Fiction gets the lion’s share of my reading time – I’m looking forward to Ian McEwan’s Machines Like Me – and genre fiction a good part of that. Scandinavian and Icelandic murder mysteries – the darker the better – plus well-researched historical fiction from the likes of C.J. Sansom, Philip Kerr and Hilary Mantell are particular treats.

“If I ate or drank the way I read, I’d likely be dead. I simply cannot be without a book on the go. So I read the way a chain-smoker smokes.”

Form and genre aside, however, when it comes to reading – reading anything – I am an addict. If I ate or drank the way I read, I’d likely be dead. I simply cannot be without a book on the go. So I read the way a chain-smoker smokes. When I finish a book in bed, no matter how late it is, I can’t turn off my light and go to sleep until I’ve chosen a new one from the crowded shelf of my night table. Then I have to read at least a page or two – enough to justify inserting a fresh bookmark.

Though I have nothing against e-books or electronics in general, I am grateful for the continued existence of the physical book and its sidekick, the paper bookmark. I keep a collection of bookmarks in a wicker basket on the same shelf that houses my books-in-waiting. I have bookmarks advertising independent book stores – some that closed decades ago and some still thriving. I have bookmarks with author photographs and pithy quotes (Edith Sitwell: “I have often wished I had time to cultivate modesty … But I am too busy thinking about myself.”) I have bookmarks from art galleries, museums and churches; bookmarks commemorating literary events, weddings and funerals; bookmarks laminated to preserve dried flowers; even a couple of clumsy homemade efforts that I won’t describe. I do not possess anything sporting inspirational messages, sparkles, sequins, tassels, holograms or depictions of unicorns. And yes, though I don’t make a fetish of it, I do try to match bookmark to book. At least, I go for a degree of compatibility – dark with dark, whimsical with whimsical.

“But it all comes down to the heft in the hand of the single book. The delicate turning of each page.”

Physical books, of course, take up physical space. My apartment is lined with shelves: the biography shelf; the poetry shelf; the shelf for anthologies; my small library of raven and crow books (I have a thing about ravens and crows); and a shelf I had custom-made to fit a certain nook and house my books on religion and spirituality. Then there are the big main shelves for all the fiction – starting in the living/dining room with Caroline Adderson’s Bad Imaginings and snaking around to end up in the bedroom with Emile Zola’s Nana.

My book shelves serve as more than just storage, however. When I have guests, they can spur conversation – Oh, I see that you’ve read… They have aesthetic value, too. Looked at abstractly, the spines with their varying colours, thicknesses and heights are like rhythmic music for the eye.

But it all comes down to the heft in the hand of the single book. The delicate turning of each page. The sight of the unread portion getting thinner. And the almost guilty anticipation of the next good read.

K.D. Miller has published short stories, essays and a novel. Her recent collection of stories, Late Breaking, was inspired by the paintings of Alex Colville.

Photo by Ria Puskas on Unsplash