Month: June 2020

Finding the Form with Fraser Calderwood

My story in TNQ, called “Raft,” started as a fragment in a journal. But the fragment itself never made it into the finished piece.

I had been working on another piece, titled “Androids,” and I was really enjoying writing this character, the protagonist’s father, who was very much a caricature of my own dad. It was perhaps the first time I had used my dad in fiction. I’ve been writing variations on my mother for years, which seems like a more serious crime. Writing my dad was a lark. I would start with one true image—in that story a man who stumbles in late from work and is seen with suit and tie still on, but with his whole hand caught in a pickle jar like a raccoon, trying to fish out a good pickle—and then expand him until he was a person. And he would always be akin to my father, but just constructed out of that one detail, not so much a double as a long-lost half-brother.

Pivotal to the first draft of that story was this fragment, a memory about shoe shopping when I was a kid. My mother took us for most of our clothes, but I remember, as I got to fourth or fifth grade, my dad took over the shoe shopping. In that kid logic, I reasoned that shoes were expensive, and Dad knew we didn’t have a lot of money, so being in charge of shoes let him control the budget. I have these two anecdotes: a set-up and a pay-off. One is of the sort of silent auction that usually took place, where I would try to guess what my dad’s budget was for shoes and aim for it. I wanted a cool brand, but I never wanted to ask for too much. However, like The Price is Right, if what I asked for was close to his price without going over, he would be impressed with that thriftiness and suddenly the budget would expand. “I just want you to get the right shoes,” he’d always say. The second anecdote is about one time my mom had to handle this procedure. She took me to the Army & Navy, I remember, on Columbia Street in New Westminster, which is sort of like a military surplus store grafted onto a Winners. I told her these clunky, awful things were the shoes I liked. The brand was called “Look.” Each O was an eye. Mom didn’t see I was bluffing. She didn’t know the rules of the game. So, I came home with the shoes. And I remember her saying to my dad, almost in protest or apology, “He said these were the ones he liked!”

A major part of short story writing is eliminating characters. You start with a real family, but that’s too much for 5000 words. So, you start killing them off, sending them on long vacations.

The scene took up about 500 words. It became too long a digression, too much ballast for the thing to get off the ground. So, I saved it, and like a scrap of potato I sprouted another story from it. That story would become “Raft.” In addition to the shoe story, I had a scene with the father, secretly and out of a sense of responsibility, dashing on some rocks a raft his son has laboured to build. But again, by the second draft, the unwieldy shoe story had to be lopped off. Instead, the raft scene wrapped around and became a frame for the present-day story that’s sort of about the liberal/progressive divide. This was something I hadn’t done: having the past frame the present is less common than the inverse, I think. It seemed to present a problem, because the story’s conclusion would not be chronologically the last event.

At the same time, I was tutoring students who were learning English. One of my students liked to read out loud and have me correct his pronunciation. He needed a story in which he could practice different verb tenses, as well. I found Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral.” We have twenty or so different anthologies, and I swear “Cathedral” was in every one of them.

I admire Carver, but “Cathedral” wasn’t one of the Carver stories I found particularly memorable. As my student was sounding it out, I couldn’t see what made it work the way it does. This utter grouch, who resents his wife having friends, hosts his wife’s blind friend and together they draw a cathedral. They get drunk and then they decide to also get stoned—which in my experience seldom improves the night, unless your aim is to fall asleep. And yet, the story works. It must: it’s in so many anthologies!

Later, I wanted to see if I could repeat the experiment. What I wanted to borrow of its form was the great turn at the end when the wife enters and finds them in that awkward position, her husband leaning over the blind man and guiding his hand as he draws the church. I wanted to see if I could construct a scene similar to that.

A major part of short story writing is eliminating characters. You start with a real family, but that’s too much for 5000 words. So, you start killing them off, sending them on long vacations. In this story, that meant drowning the mother. You seal off rooms, eliminate possibilities. What I ended up with was the son’s girlfriend Jane—who I’d given an excuse not to be in the room—changes her mind and finds the men in a surreal and slightly compromised moment. I threw in the two men smoking a joint after they were already drunk as a little nod to Carver.

Fraser Calderwood grew up between Vancouver and Calgary, but currently lives in Toronto, where he is an MFA candidate at the University of Guelph. He is working on his first novel.

Cover Photo by Anna Dziubinska on Unsplash

Finding the Form with Pearl Pirie

Since I write on computers, I don’t tend to have physical byproducts of process, but for one of the poems in this issue of TNQ, I have a photo of the moment I am describing. A terrible, grainy photo that even K.I.T.T. couldn’t enhance enough. The poem does the job though, I hope.

Since I write on computers, I don’t tend to have physical byproducts of process, but for one of the poems in this issue of TNQ, I have a photo of the moment I am describing. A terrible, grainy photo that even K.I.T.T. couldn’t enhance enough. The poem does the job though, I hope.

At the level of poem, I can move things in my head or on screen. Thirty years into writing seriously, edits happen quickly. I need paper to edit at the unit of book for marking out gaps, redundancies, or ill-fits. Since the poems in this spring issue are from the forthcoming book footlights (Radiant, 2020), there were hardcopy scribblings, but the papers from those edits were recycled almost a year ago.

The poems “waiting for menus” and “adaptive” are at the same end of the editing spectrum. Unlike some poems that I tinker with, or assemble from bits over a year or two, (or eight or ten years), these, like my most affecting poems, came out in a rush. They were nearly in their final form for words and order, only needing lineation to control density and speed. The poems that are like pulling teeth are necessary too because they teach how to write and how to work things out. They are the groping that make the laying of hands on things easier later.

The moment for “waiting for menus” was October 28, 2018. I only had to transcribe at the window side table. It took longer to narrate than it did to occur. It was like an enacted poem staged for me. It is purely autobiographical from Chinatown Ottawa. The scene felt as perfect as using an animated gif as a metaphor for injustice.

Most of the wording is the same as the first draft. I added a phrase, or word here and there, and moved a couple phrases for clarity and impact. Initially, for example, I used a pronoun, not mentioning until much later it’s a pigeon we’re talking about. I had to confirm I was right about the hawk species, but it looked like the same hawk as coincidentally reported just earlier in the week in Ottawa Field Naturalists.

I added line breaks to slow the pace but it largely flew into my hands fully formed.

In contrast, the origins of “adaptive” came from pondering. It was an attempt to comfort a friend who was hurting from suddenness of divorce in 2018. It showed me the use of poems when linear words feel helpless.

Normally, all my first drafts are saved in files titled as year-month-drafts, but May of that year is missing. I remember I started with what is now the first couplet and the image of swaddling pears and the question of where to go from there. What happens to fruit when it gets soft? How do they get injured? What purpose does it serve?

The first idea was of protecting people in softness, a tender achy mood of empathy. I needed to say: it gets better. Right or wrong, probably wrongly, I proposed the idea of injury as causing productive growth, even if the hurt doesn’t feel appreciated at the time. (I wince now.)

It’s a bit harder to track genesis, beyond the problem of a missing file. I was ruminating around bruised long grass, and healing. It being a few months since my concussion and the brain and body still being far off normal running, injury and healing were touchstones. When is injury too much injury to recover from? What is injury vs. life force? Bruise was my personal trope word for 2018 with an uptick in Sept 2016 too. For example, “heritage varieties of tomatoes that a breath could bruise.” (I think that stemmed from when I broke a few ribs dropping 2x4s on them when I tripped. )

Digesting the idea of helplessness of being left and the ephemerality it represents may have started to be expressed within my haiku:

late winter—

bruises go right through

the Cortland apple

It is in the same orchard as a series of haiku where I turned over the idea of people in domestic violence, eating around the fruit’s bruises. Or such as the one that came out in my haiku series published in Not Quite Dawn (Éditions des petits nuages, March 2020)

eating the apple

and its bruises—

she won’t leave him

I have a soft spot for haiku, naturally after decades doing them. These came into play as tools for understanding a pain in life. As I edited “adaptive”, I realized how the analogies were failing, so I broke the fourth wall to admit as much. I tried to commiserate about all the helpers with unsolicited advice, and reassure. I wanted to point a spotlight on the idea of choice: to sink into the hurt, or move beyond.

Speaking of moving beyond, I’ve tended to avoid novels but over the last 3 years have been reading a lot of them and attempting to write one. I still default to poetry, various sub-genres of, but I explore all genres (poetry, fiction, short stories, nonfiction, visual art, photography).

I love making poems in couplets and triplets. I guess I’ve been at that a while. Vertigoheel for the Dilly (above/ground, 2014) was playing with bastard ghazals. These poems in TNQ also embrace my love of couplets. Couplets don’t tumble forward like triplets, but force a slower pacing without the closure and authority of quatrains or the sense of one gush of narrative like a single stanza poem. They encourage you to take it one piece at a time in small chunks which is something of my approach to life since the concussion, switch from urban to rural and greater focus on health.

Pearl Pirie’s fourth collection, footlights, (Radiant Press, Oct 2020) contains the poems published here. Her most recent chapbook is Not Quite Dawn, from Éditions des petits nuages in out spring 2020. Her previous poetry collection, the pet radish, shrunken (Book*hug, 2015), won the Lampman Award. www.pearlpirie.com

Photos provided by Pearl Pirie

Amanda Jernigan’s Writing Space

These days I write from my Hiram-shack, which is to say, from my shack by the ramshackle sea. The reference is to the abode of Hiram, the banjo-playing protagonist of Richard Outram’s book Hiram and Jenny.

I have a mouth organ rather than a banjo, but otherwise, same same. ‘Every work of art is a prophecy,’ wrote Oscar Wilde. I think of that sometimes as, looking out over ragged remembering waves, I recollect the collection’s opening poem:

Hiram with Banjo

by Richard Outram, from Hiram and Jenny (Porcupine’s Quill, 1988)

The broken-off telephone pole

by the shack by the ramshackle sea

points nowhere. The tilted sky is green.

He grins. He admires to see

blue smoke from the three-legged stove

torn over the lion dunes

and swirled in the serpent grass.

He plucks at old crimson tunes,

and spits with the wind. Black rocks beat back

ragged remembering waves.

He is going to have him another drink.

Or two. Well, Jesus saves.

Amanda Jernigan writes for music and the stage, and is the author of three books of poetry, including Years, Months, and Days, a New York Times ‘Best Book’ of 2018. She teaches at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax.

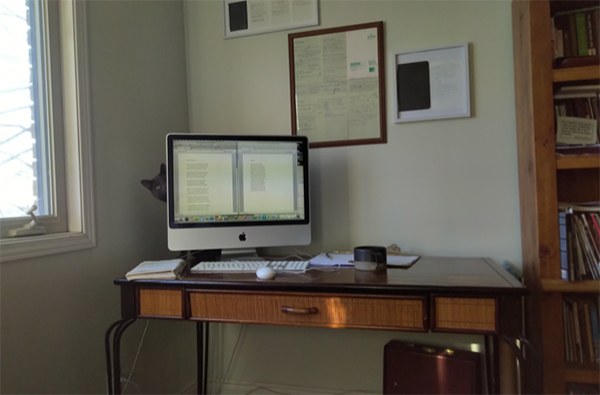

Finding the Form with Barbara Tran

I wrote the first draft of “Laws of Motion” at this desk, this desk which has followed me from Virginia to Vermont to Toronto to California and back to Toronto, where I look forward to rejoining it this August. For the time being, I am in California again. Outside the window, lavender trumpet vine dances and dapples. The brightness of the day belies the darkness of recent times.

The protagonist of “Laws of Motion” is trapped by conflict, by age, by forces beyond her control, in a place where she does not feel at home. I wish the story’s subject matter was a thing of the past, an experience to be preserved in cautionary tales.

In the time between submission of the original version of this post and the day final copy was due, developments necessitated its updating.

The original text continued thusly:

A 25-year-old man was out for a jog.

Two men followed the jogger in a truck. They brought shotguns.

The two men thought the one looked suspicious. They watched him, in his khaki shorts and white T-shirt, his Nikes, jogging, and they decided he might be armed.

The pair drove after, cornered, and confronted the jogger. They shot and killed him.

Outside of that, nothing happened. Not for two months.

This story only makes sense when you fill in the colours of the man killed and the gunmen. For, if it were the reverse, others would likely have been killed. At the very least, there would have been immediate arrests and outrage. Waves of reverberating violence. Instead, over two months later, we are just learning about Ahmaud Arbery’s murder.

Between the original submission of this post and its re-submission, more black lives have been lost in North America as a result of rampant racism. The two more widely publicized, killed by American police: Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. The death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet remains under investigation in Toronto.

My writing space is no oasis. My writing space is my living space is my walking the dog space is my thinking space is my running space is any space where my body is is a safer space than the same space occupied by certain other bodies is a more risky space than the same space occupied by certain other bodies is a space where inequality frequently enters the picture.

It is my fervent hope that our experience with Covid-19, while challenging, will not be without a silver lining. Travelers worldwide are now discovering what it is to be the subject of suspicion, a person from elsewhere, carrying who knows what on their bodies, in their bodies. A virus, the great leveler. Now, we are all suspect.

I hold out hope that we will emerge from this experience a bit wiser, that our time spent isolated and uncertain will give those of us in more protected positions reason to pause and consider what it is to be perpetually under question, and that, from this vulnerable position, we might find in ourselves more patience, empathy, and compassion for one other.

Barbara Tran is indebted to Hedgebrook for radical hospitality at a crucial time, and to the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for essential support. In 2020, Barbara’s writing will appear in Bennington Review, Canthius, Cincinnati Review, The New Quarterly, Ploughshares, and Poetry.

Photo by Holger Link on Unsplash

What is Kate Cayley Reading?

Right now (in the state of semi-isolation we’re all in), I tend to turn to writers who seem to view the world at a distance, who describe precisely without sentimentality, and who don’t lie, meaning who don’t indulge in emotional histrionics. Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse, which I’ve never read even though I reread Mrs. Dalloway approximately once a year. Rereading Yiyun Li’s short stories, which have such clarity and such mistrust of melodrama.

I think of Li as my friend, though I’ve never met her (I saw her interviewed once and babbled as she signed a book for me—she was very gracious), the way books can be companions, touchstones for your own experience or perception or even your opinions about domestic life, political life. I’ve just started Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How To Pronounce Knife.

“…books can be companions, touchstones for your own experience or perception or even your opinions about domestic life, political life.”

She’s the kind of writer who conceals how technically brilliant she is. Her economy is astonishing—you feel yourself to be in the presence of someone who will not waste a second of your time, who will tell you exactly what you need to know, and who will only tell the truth.

All that said, I’m also on the hunt for the great comic novel, and open to suggestions. Something really silly. I should probably go for something like War and Peace or finally tackling Proust, but with three kids home from school, reading still mostly happens in the hour before turning out the light.

Kate Cayley has published a collection of short stories and two collections of poetry. Her second collection of short stories is forthcoming from Biblioasis.

Photos courtesy of João Silas on Unsplash

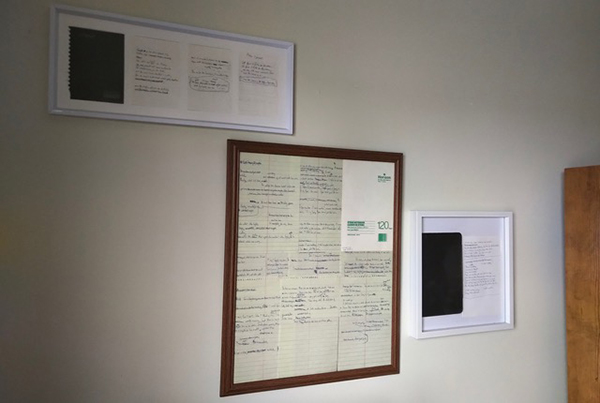

Jason Heroux’s Writing Space

A desk, a computer, a pen, and a couple of pads of paper – some scribbled, some blank, plus a cup of freshly ground French Roast coffee. A shy cat named Pablo behind the monitor. The window to the left lets in light, birdsong, and traffic-song, reminding me of the here-and-now, and on the wall hang framed pages of a few old notebooks throughout the decades reminding me of the there-and-then.

My favourite part of this space is the natural light during the day. It always feels balanced. Never too bright, or too dim. Most of my inspiration comes through the window. Clouds. Ambulances. City buses. Trees. Factory smoke. Laughter. Insects. Silence. A world going about its business, and the wonder it brings.

What I enjoy most about this writing space is that it feels like an intersection where the day and I can cross paths and join together on a little journey before we’re ultimately forced to go our separate ways.

Jason Heroux is currently the Poet Laureate for the city of Kingston, Ontario. His most recent book is the novel Amusement Park of Constant Sorrow (Mansfield Press, 2018).

Photo by Tarik Haiga on Unsplash

What is Theressa Slind Reading?

Concentrating during global pandemics is tricky, I’m learning, as is feeling a sense of control over one’s life. Who knew? The results: wall washing and fridge cleaning, reorganized book shelves, daughter’s bedroom painted a cheery Jamaican Aqua to replace the subfusc brown that came with the house over ten years ago (my brother tells me I’m lucky my daughter hasn’t sued for emancipation), and an even more scattered reading life than usual. Here’s the scattering.

First, there’s the assorted delights offered by the internet and magazine subscriptions: a New Yorker vocabulary-builder about avalanches (sinter, albedo); a heart-breaking essay about an off-the-grid, double suicide; another personal essay from Outside, Murder on the Appalachian Trail (I’m into the human element in outdoor adventure); anxiety reading such as Record of a Pandemic from The Walrus. It goes on. And then there are the books.

Let’s start by giving thanks for Hilary Mantel. I’m half-way through the newest in her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, The Mirror & the Light, and, like Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies, it’s genius, the perfect book for now (or any time). The first paragraph contains this sentence: “The morning’s circumstances are new and there are no rules to guide us.” It felt right from the start. Maybe because the first book I read of Mantel’s was Beyond Black, a novel about a medium, I find her ability to inhabit characters spooky. Like she’s a medium through which Thomas Cromwell speaks. And this Cromwell is the best: tough, funny, loyal, ruthless, kind, vulnerable, haunted, fatherly, shrewd, surprised to learn he looks like a murderer. He’s the smartest guy in the room, but it can’t end well and I read on filled with dread. Bonus: The Mirror & the Light has taught me a new word to describe the former colour of my daughter’s bedroom and, coincidentally, my pandemic mood and style: subfusc.

On my walks—now we thank public libraries and the outdoors—I’m listening to the audiobook, Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family by Robert Kolker. I like that subtitle with its singular mind, as if this family with its twelve (!!) children, six (!!!) of whom were diagnosed with schizophrenia, became trapped inside one unwell mind. Kolker has an elegant writing style and the story he’s telling is fascinating and tragic. I still can’t get over the fact that the first ten of Mimi Galvin’s twelve children were—with apologies to boys—boys! Ten! Okay, enough exclamation points. Just read it (or find an audio version; I could listen to the narrator, Sean Pratt, all day).

“Bonus: The Mirror & the Light has taught me a new word to describe the former colour of my daughter’s bedroom, and, coincidentally, my pandemic mood and style: subfusc”

Over the last few weeks, I’ve dipped into New American Stories edited by Ben Marcus, and, based on the introductory essay and the first story, “Paranoia,” by Saïd Sayrafiezadeh, it’s going to be great. In his essay, Marcus describes reading good stories as inviting “cyclones of feeling into our bodies”, the story as a “sequence of language that creates a chemical reaction.” Agreed! I bought the book after reading this Granta interview between Ben Marcus and George Saunders. You’re welcome. If that’s not your style or you need a palate-cleanser, enjoy this tart (tart like a Granny Smith) pep talk from Elif Batuman I recently stumbled upon. I must read more of her work, but Leaving the Sea: Stories by Ben Marcus is up first. Yes, I’ve started reading this one as well.

Another book I have on the go is 97,196 Words: Essays by Emmanuel Carrère. He reminds me of a very male, very French Janet Malcolm. I borrowed this one from the library (never to be returned?) after reading the best true crime story ever by Carrère: The Adversary: A True Story of Monstrous Deception. Sounds sensational, and it is, but Carrère’s writing has range and depth and feeling. If you want the short version there’s an essay in 97,196 Words (maybe 6,127 words?) about the same story of Jean-Claude Romand. You’ll want to have it at the ready if we ever have dinner parties again—and then can ever stop talking about disease, self-isolation, and socioeconomic fallout. On the other hand, what’s more sick, isolating, and economically and socially precarious than lying to friends and family for eighteen years that you’ve graduated from medical school and work as a researcher at the WHO, driving to “work” every day in Switzerland, only to read all day in your car or go for walks in forest. And then you kill everyone and the dog. Yes, post-COVID-19 dinner party guests will still want to hear this one. Take heart, we’ll be able to share stories in person again one day. Mine will be scattershot.

Theressa Slind is a librarian and writer. Her fiction has appeared in subTerrain, Grain, and The New Quarterly. She lives in Saskatoon.

Photos courtesy of freestocks on Unsplash

What is Pam Dillon Reading?

I am an unrepentant bibliophile and book collector. Once I fall in love with an author’s work, I’m determined to read as much of their writing as I can find. The other literary practice I have is to read more than one book at a time, often switching between fiction, nonfiction, and or poetry. However, I’m reading three books at the moment because I have some extra time. Every one of them is written by a unique, delightful, and talented writer.

Poetry ~ NDN Coping Mechanisms – Notes from the Field by Billy-Ray Belcourt.

This book of poems is brilliantly crafted, expansive, revealing, audacious, cerebral, and mesmerizing. I parse it out to myself in small portions wanting to savour each poem. His Griffin Poetry Prize winning first collection – This Wound is a World shocked me awake with its beauty, and its gripping honesty. This second collection is equally as good. Read this poet, you won’t be able to look away.

Nonfiction ~ A Mind Spread Out on The Ground by Alicia Elliott.

A collection of essays by an author whose ability to weave the hard and cruel narrative of Canada’s treatment of First Nations people with memoir reveals the deft of her skill. You can’t read this book and be removed, nor should you. This is the story of one woman’s’ call to action on the behalf of many. The essays have a breadth of knowledge that reawakens your hidden assumptions about Canada and slaps you in the face. It’s good. It’s the medicine we need. I’m reading the chapter, “Not Your Noble Savage” and realizing I know so little truth. Our national “fairy tale” has to end, if we’re ever to truly reconcile this terrible history. We’ve swept the truth under our collective settler unconscious and it must be faced. Alicia Elliott writes it down: it’s fierce, beautiful, and painfully real, but that’s what makes it so transformative.

Fiction ~ Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice.

I confess this is my second reading of this novel, I liked it that much. Though published a couple of years ago, it’s perfect reading for these times. Have you ever wondered what you’d do if you woke up and everything you relied upon was changed? Sound familiar? Here we are in the middle of a pandemic and this story is just what you need. All the pieces of modern civilisation still exist at the moment, but what if they didn’t? How would you cope? This is one of the themes that carries through Moon of the Crusted Snow. I loved the deft way that Waubgeshig Rice tells the story of one family and their community in the midst of societal collapse. In the authors quietly controlled voice, he reveals the importance of family, community, and the values that define who you are and who you become in times of crisis. The author takes a restrained approach to the tale in a way that makes this story a haunting revelation about our collective human nature.

Yes, every one of my current reads is an Indigenous writer and that’s not by accident.

To quote musician Jeremy Dutcher on the eve of his Polaris Prize win, “You are in the midst of an Indigenous renaissance . . . Canada are you listening? It is being laid bare for you, so are you going to take it up? I see such a beautiful way forward.” I believe him. There is an expanding and brilliant light revealing the talents of Indigenous writers, visual artists, musicians, dancers, and others in the performing arts. We are so fortunate to be able to witness and support this renaissance!

Pam Dillon is a writer, poet, and graduate of creative writing from the University of Toronto. Pamela’s publications can be found on literary websites and print journals including the CBC Books – Canada Writes, and The Globe and Mail. She is currently working on a collection of short stories.

Photos courtesy of Pam Dillon.